Ikebana (生け花, 活け花, 'arranging flowers' or 'making flowers alive') is the Japanese art of flower arrangement.[1][2] It is also known as kadō (華道, 'way of flowers'). The tradition dates back to Heian period (794–1185), when floral offerings were made at altars. Later, flower arrangements were instead used to adorn the tokonoma (alcove) of a traditional Japanese home.

Ikebana is counted as one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement, along with kōdō for incense appreciation and chadō for tea and the tea ceremony.

Etymology

The term ikebana comes from the combination of the Japanese ikeru (生ける, 'to arrange (flowers), have life, be living') and hana (花, 'flower'). Possible translations include 'giving life to flowers' and 'arranging flowers'.[3]

History

The pastime of viewing plants and appreciating flowers throughout the four seasons was established in Japan early on through the aristocracy. Waka poetry anthologies such as the Man'yōshū and Kokin Wakashū from the Heian period (794–1185) included many poems on the topic of flowers.[4] With the introduction of Buddhism, offering flowers at Buddhist altars became common. Although the lotus is widely used in India where Buddhism originated, in Japan other native flowers for each season were selected for this purpose.[4]

For a long time the art of flower arranging had no meaning, and functioned as merely the placing in vases the flowers to be used as temple offerings and before ancestral shrines, without system or meaningful structure. The first flower arrangements were composed using a system were known as shin-no-hana, meaning 'central flower arrangement'. A huge branch of pine or cryptomeria stood in the middle, with three or five seasonable flowers placed around it. These branches and stems were put in vases in upright positions without attempting artificial curves. Generally symmetrical in form, these arrangements appeared in religious pictures in the 14th century, as the first attempt to represent natural scenery. The large tree in the centre represented distant scenery, plum or cherry blossoms middle distance, and little flowering plants the foreground. The lines of these arrangements were known as centre and sub-centre.[5]

Later on, among other types of Buddhist offering, placing mitsu-gusoku became popular in the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Nanboku-chō periods (1336–1392).[4] Various Buddhist scriptures have been named after flowers such as the Kegon-kyo (Flower Garland Sutra) and Hokke-kyo (Lotus Sutra). The Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga ('Scroll of Frolicking Animals and Humans') depicts lotus being offered by a monkey in front of a frog mimicking the Buddha.[4][6]

With the development of the shoin-zukuri architectural style starting in the Muromachi period (1336–1573), kakemono (scroll pictures) and containers could be suitable displayed as art objects in the oshiita, a precursor to the tokonoma alcove, and the chigaidana, two-levelled shelves. Also displayed in these spaces were flower arrangements in vases that influenced the interior decorations, which became simpler and more exquisite over time.[5] This style of decoration was called zashiki kazari (座敷飾).[7] The set of three ceremonial objects at the Buddhist altar called mitsugusoku consisted of candles lit in holders, a censer, and flowers in a vase. The flowers in the vase were arranged in the earliest style called tatebana or tatehana (立花, 'standing flowers'), and were composed of shin (motoki) and shitakusa.[8] Recent historical research now indicates that the practice of tatebana[9] derived from a combination of belief systems, including Buddhist, and the Shinto yorishiro belief is most likely the origin of the Japanese practice of modern ikebana. Together, they form the basis for the original, purely Japanese derivation of the practice of ikebana.

The art of flower arranging developed with many schools only coming into existence at the end of the 15th century following a period of the civil war. The eighth shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–1490), was a patron of the arts and the greatest promoter of cha-no-yu – tea ceremony – and ikebana, flower arrangement. Yoshimasa would later abdicate his position to devote his time to the arts, and developed concepts that would then go on to contribute to the formulation of rules in ikebana; one of the most important being that flowers offered on all ceremonial occasions, and placed as offerings before the gods, should not be offered loosely, but should represent time and thought.[5]

Yoshimasa's contemporaries also contributed heavily to the development of flower arranging; the celebrated painter Sōami, a friend of Yoshimasa, conceived of the idea of representing the three elements of heaven, humans, and earth, from which grew the principles of arrangements used today in some ikebana schools. It was at Yoshimasa's Silver Pavilion in Kyoto that ikebana received its greatest development, alongside the art of tea ceremony and ko-awase, the incense ceremony.[5]

Artists of the Kanō school, such as Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506), Sesson, Kanō Masanobu, Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559), and Shugetsu of the 16th century, were lovers of nature, and ikebana advanced a step further in this period beyond a form of temple and room decoration, with greater consideration given to the natural beauty of a floral arrangement. At this time, ikebana was known as rikka.[5]

During the same time period, another form of flower arranging known as nageirebana was developed; rikka and nageirebana are the two branches into which ikebana has been divided. Popularity of the two styles vacillated between these two for centuries. In the beginning, rikka was stiff, formal, and more decorative style, while nageirebana was simpler and more natural.[5]

Although nageirebana began to come into favour in the Higashiyama period, rikka was still preferred, and nageirebana did not truly gain popularity until the Momoyama period, about a hundred years after Ashikaga Yoshimasa. It was at this period that tea ceremony reached its highest development and strongly influenced ikebana, as a practitioner of tea was most probably also a follower of ikebana.[5]

As a dependent of rikka, nageirebana branched off, gaining its independence and its own popularity in the 16th century for its freedom of line and natural beauty. Both styles, despite having originated in the Higashiyama period, reflect the time periods in which they gained popularity, with rikka displaying the tastes of the Higashiyama period, and nageirebana the tastes of the Momoyama period. Rikka lost some of its popularity during the Momoyama period, but in the first part of the Edo period (1603–1668) was revived, and became more popular than ever before.[5] In the Higashiyama period, rikka had been used only as room decorations on ceremonial occasions, but now was followed as a fine art and looked upon as an accomplishment and pastime of the upper classes.[5] Rikka reached its greatest popularity during the Genroku era.[5]

Ikebana has always been considered a dignified accomplishment. All of Japan's most celebrated generals notably practised flower arranging, finding that it calmed their minds and made their decisions on the field of action clearer; notable military practitioners include Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of Japan's most famous generals.

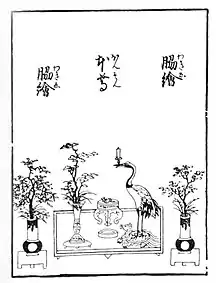

Many works of various schools on ikebana were published in the centuries from the Ken'ei (1206–1207) to the Genroku (1668–1704) eras, all founded on Sōami's idea of the three elements. A number of texts documenting ikebana also existed, though few contained directly instructional content; however, these books were fully illustrated, thus documenting the gradual progress of the art.

During the early Edo period (17th century), publications in Japan developed rapidly. Books about ikebana were published in succession. During this time, the Sendenshō (仙伝抄) was published, the oldest published manual. The Kawari Kaden Hisho (替花伝秘書) was published in Kanbun 1 (1661). This was carefully written and instructive ikebana text, with rules and principles detailed in full,[5] and was the second publication of ikebana texts in the Edo period after the Sendenshō. Although the text is similar to the contents of commentaries of the Muromachi period, the illustrations showed how to enjoy tachibana, which had spread from monks to warriors and further on to townspeople. The Kokon Rikka-shu (古今立花集) was the oldest published work on rikka in Kanbun 12 (1672). The Kokon Rikka-taizen (古今立花大全), published in Tenna 3 (1683), was the most famous rikka manual. The Rikka Imayō Sugata (立華時勢粧) came out Jōkyō 5 (1688).

In the Ken'ei era, rikka was simple and natural, with no extreme curves in the arrangement, but in the Genroku era, the lines became complicated and the forms pattern-like, following general trends of high artistic development and expression within that period; during the Genroku period, all the fine arts were highly developed, above all pattern-printing for fabrics and decoration. In the latter part of the 17th century, Korin, the famous lacquer artist known for his exquisite designs, strongly influenced ikebana. In this period, the combination of a pattern or design with lines that followed the natural growth of the plant produced the most pleasing and graceful results.[5]

It was in the latter part of the 17th century that ikebana was most practised and reached its highest degree of perfection as an art. Still, there were occasional departures into unnatural curves and artificial presentation styles that caused a shift, and the more naturalistic style of nageirebana was again revived. Until then, only one branch of ikebana had been taught at a time, following the taste of the day, but now rival teachers in both rikka and nageirebana existed.[5]

Rikka reached its greatest popularity in the Genroku era. From this time on nageirebana took the name of ikebana. In the Tenmei era (1781–1789), nageirebana, or ikebana, advanced rapidly in favour and developed great beauty of line. The exponents of the art not only studied nature freely, but combined this knowledge with that of rikka, developing the results of ikebana even further.

After the Tenmei era, a formal form of arrangement developed. This form has a fixed rule or model known as "heaven, human, and earth".[5] Is it known as Seika (生花).In the Mishō-ryū school, the form is called Kakubana (格花).

The most popular schools of today, including Ikenobō, Enshū-ryū, and Mishō-ryū, amongst others, adhere to some principles, but there are in Tokyo and Kyoto many masters of ikebana who teach the simpler forms of Ko-ryū, and Ko-Shin-ryū of the Genroku and Tenmei eras.[5]

The oldest international organisation, Ikebana International, was founded in 1956;[10] Princess Takamado is the honorary president.[11]

Practitioners

Followers and practitioners of ikebana, also referred to as kadō, are known as kadōka (華道家). A kadō teacher is called sensei (先生).

Noted Japanese practitioners include Junichi Kakizaki, Mokichi Okada, and Yuki Tsuji. At a March 2015 TEDx in Shimizu, Shizuoka, Tsuji elaborated on the relationship of ikebana to beauty.[12]

After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami devastated Japan, noted ikebana practitioner Toshiro Kawase began posting images of his arrangements online every day in a project called "One Day, One Flower."[13][14]

Another practitioner is the Hollywood actress Marcia Gay Harden, who started when she was living in Japan as a child,[15] and has published a book on ikebana with her own works.[16] Her mother, Beverly Harden, was a practitioner of the Sōgetsu school.[17][18] She later became also president of the Ikebana International Washington, DC chapter.[19]

Schools

Mary Averill (1913) gives an overview of the numerous schools of ikebana. A school is normally headed by an iemoto, oftentimes passed down within a family from one generation to the next.[20] The oldest of these schools, Ikenobō goes back to the 8th century (Heian period). This school marks its beginnings from the construction of the Rokkaku-dō in Kyoto, the second oldest Buddhist temple in Japan, built in 587 by Prince Shōtoku, who had camped near a pond in what is now central Kyoto, and enshrined a small statue of her.

During the 13th century, Ono-no-Imoko, an official state emissary, brought the practice of placing Buddhist flowers on an altar from China. He became a priest at the temple and spent the rest of his days practising flower arranging. The original priests of the temple lived by the side of the pond, for which the Japanese word is ike (池), and the word bō (坊), meaning priest, connected by the possessive particle no (の), gives the word Ikenobō (池坊, 'priest of the lake'). The name 'Ikenobō', granted by the emperor, became attached to the priests there who specialised in altar arrangements.

Ikenobō is the only school that does not have the ending -ryū in its name, as it is considered the original school. The first systematised classical styles, including rikka, started in the middle of the 15th century. The first students and teachers were Ikenobō Buddhist priests and members of the Buddhist community. As time passed, other schools emerged, styles changed, and ikebana became a custom among the whole of Japanese society.[21]

- Ikenobō (池坊) is a development of rikka and considered the oldest school

- Shōgetsudo Ko-ryū – originated by the monk Myōe (1171–1231)

- Ko-ryū (古流) – originated by Ōun Hoshi or Matsune Ishiro (1333–1402)

- Higashiyama Jishō-in-ryū (東山銀閣院流) – originated by shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–1490), who was also called Higashiyama-dono or Jishō-in. Branches of this school are:

- Senzan-ryū

- Higashiyama-Ko-Sei-ryū

- Higashiyama-ryū (東山流)

- Sōami-ryū (相阿弥流)

- Senke-Ko-ryū – originated by the famous tea master Sen no Rikyū in 1520

- Bisho-ryū – originated by Goto Daigakunokami or Bishokui Dokaku in 1545

- Enshū-ryū (遠州流) – originated by Lord Kobori Enshū (1579–1647). The branches of this school are numerous:

- Nihonbashi Enshū-ryū

- Shin Enshū-ryū

- Ango Enshū-ryū

- Miyako Enshū-ryū

- Seifu Enshū-ryū

- Asakusa Enshū-ryū, as well as many others.

- Ko-Shin-ryū – originated by Shin-tetsu-sai, who was the teacher of shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada (1579–1632)

- Sekishu-ryū – originated by Katagiri Iwaminokami Sadamasa (1604–1673)

- Jikei-ryū – originated by Shōuken Jikei in the year 1699

- Senkei-ryū – founded around 1669 by Senkei Tomiharunoki

- Tōgen-Ryu – commenced by Togensai Masayasu about 1716

- Sōgensai

- Murakumo-ryū

- Tōko-ryū

- Shikishima-ryū

- Dōnin-ryū

- Gengi-ryū – commenced by Chiba Ryōboku in the year 1772

- Mishō-ryū (未生流) – founded by Ippo Mishōsai (1761–1824) in Osaka

- Yōshin Go-ryū – developed during the Edo period

- Sei-ryū – commenced by Dōseiken Ittoku in 1818

- Shōko-ryū – commenced by Hakusuisai in the year 1896

- Ohara-ryū (小原流) – founded in 1895 by Ohara Unshin

- Sōgetsu-ryū (草月流) – founded in 1927 by Teshigahara Sofu

- Saga Go-ryū (嵯峨御流) – founded in the 1930s with roots dating back to Emperor Saga, who reigned from 809–823 CE

- Ichiyō (一葉) – founded in 1937

Other schools include Banmi Shōfū-ryū (晩美生風流), founded in 1962 by Bessie "Yoneko Banmi" Fooks, and Kaden-ryū (華伝流), founded by Kikuto Sakagawa in 1987 based on the Ikenobō school.

Theory

Since flower arrangement (Chinese: 插花; pinyin: chāhuā) arrived in Japan from China together with Buddhism, it was naturally imbued with Chinese and Buddhist philosophy. The Buddhist desire to preserve life lies at the root of much of ikebana practice, and has created most of the rules of flower arrangement, controlling also the shapes of the flower vases, formed as to help to prolong the life of the flowers.[22] Consideration of the vase as being something more than a mere holder of the flowers is also an important consideration. The surface of the water is always exposed, alongside the surface of the earth from which the grouping of flowers springs. This aids in creating the effect of representing a complete plant growing as nearly as possible in its natural conditions.[22]

More than simply putting flowers in a container, ikebana is a disciplined art form in which nature and humanity are brought together. Contrary to the idea of a particoloured or multicoloured arrangement of blossoms, ikebana often emphasises other areas of the plant, such as its stems and leaves, and puts emphasis on shape, line, and form. Though ikebana is an expression of creativity, certain rules govern its form, such as the idea of good and evil fortune in the selection of material and form of the arrangement.

The concept of hanakotoba (花言葉) is the Japanese form of the language of flowers, wherein plants are given specific coded meanings, varying based on the colour of the flowers, the presence of thorns within the height of tall plants, the combination of flowers used in garlands and the different types of flowers themselves, amongst other factors. For instance, the colours of some flowers are considered unlucky. Red flowers, which are used at funerals, are undesirable for their morbid connotations, but also because red is supposed to suggest the red flames of a fire. An odd number of flowers is lucky, while even numbers are unlucky and therefore undesirable, and never used in flower arrangements. With odd numbers, symmetry and equal balance is avoided, a feature actually seldom found in nature, and which from the Japanese standpoint is never attractive in art of any description. These create a specific impression of nature, and convey the artist's intention behind each arrangement is shown through a piece's colour combinations, natural shapes, graceful lines, and the implied emotional meaning of the arrangement without the use of words. All flower arrangements given as gifts are given with the flowers in bud, so that the person to whom they are sent may have the pleasure of seeing them open, in contrast to the Western idea of flower arrangements, where the flowers are already in bloom before being given.[22]

There is no occasion which cannot be suggested by the manner in which the flowers are arranged.[22] For instance, leaving home can be announced by an unusual arrangement of flowers; auspicious materials, such as willow branches, are used to indicate hopes for a long and happy life, and are particularly used for arrangements used to mark a parting, with the length of the branch signifying a safe return from a long journey, particularly if a branch is made to form a complete circle.[22] For a house-warming, white flowers are used, as they suggest water to quench a fire; traditional Japanese homes, being made almost exclusively of wood, were particularly susceptible to fire, with everything but the roof being flammable. To celebrate an inheritance, all kinds of evergreen plants or chrysanthemums may be used, or any flowers which are long-lived, to convey the idea that the wealth or possessions may remain forever.[22] There are also appropriate arrangements for sad occasions. A flower arrangement made to mark a death is typically constructed of white flowers, with some dead leaves and branches, arranged to express peace.

Another common but not exclusive aspect present in ikebana is the employment of minimalism. Some arrangements may consist of only a minimal number of blooms interspersed among stalks and leaves. The structure of some Japanese flower arrangements is based on a scalene triangle delineated by three main points, usually twigs, considered in some schools to symbolise heaven, human, and earth, or sun, moon, and earth.[22] Use of these terms is limited to certain schools and is not customary in more traditional schools. A notable exception is the traditional rikka form, which follows other precepts. The container can be a key element of the composition, and various styles of pottery may be used in their construction. In some schools, the container is only regarded as a vessel to hold water, and should be subordinate to the arrangement.

The seasons are also expressed in flower arrangements, with flowers grouped differently according to the time of the year. For example, in March, when high winds prevail, the unusual curves of the branches convey the impression of strong winds. In summer, low, broad flower receptacles are used, where the visually predominant water produces a cooler and more refreshing arrangement than those of upright vases.[22]

The spiritual aspect of ikebana is considered very important to its practitioners. Some practitioners feel silence is needed while constructing a flower arrangement, while others feel this is not necessary, though both sides commonly agree that flower arranging is a time to appreciate aspects of nature commonly overlooked in daily life. It is believed that practice of flower arranging leads a person to become more patient and tolerant of differences in nature and in life, providing relaxation in mind, body and soul, and allowing a person to identify with beauty in all art forms.

Plants play an important role in the Japanese Shinto religion. Yorishiro are objects that divine spirits are summoned to. Evergreen plants such as kadomatsu are a traditional decoration of the New Year placed in pairs in front of homes to welcome ancestral spirits or kami of the harvest.[4]

Styles

Ikebana in the beginning was very simple, constructed from only a very few stems of flowers and evergreen branches. This first form of ikebana was called kuge (供華). Patterns and styles evolved, and by the late 15th century arrangements were common enough to be appreciated by ordinary people and not only by the imperial family and its retainers, styles of ikebana having changed during that time, transforming the practice into an art form with fixed instructions. Books were written about the art, Sedensho being the oldest of these, covering the years 1443 to 1536. Ikebana became a major part of traditional festivals, and exhibitions were occasionally held.

The first styles were characterised by a tall, upright central stem accompanied by two shorter stems. During the Momoyama period, 1560–1600, a number of splendid castles were constructed, with noblemen and royal retainers making large, decorative rikka floral arrangements that were considered appropriate decoration for castles. Many beautiful ikebana arrangements were used as decoration for castles during the Momoyama period, and were also used for celebratory reasons.

- The rikka (立花, 'standing flowers');[23] style was developed as a Buddhist expression of the beauty of landscapes in nature. Key to this style are nine branches that represent elements of nature.[24] One of rikka arrangement styles is called suna-no-mono (砂の物, 'sand arrangement').[25]

When the tea ceremony emerged, another style was introduced for tea ceremony rooms called chabana. This style is the opposite of the Momoyama style and emphasises rustic simplicity. Chabana is not considered a style of ikebana but is separate. The simplicity of chabana in turn helped create the nageirebana or 'thrown-in' style.

- Nageirebana (投入花, 'thrown-in flowers') is a non-structured design which led to the development of the seika or shoka style. It is characterised by a tight bundle of stems that form a triangular three-branched asymmetrical arrangement that was considered classic. It is also known by the short form nageire.

- Seika (生花, 'pure flowers')[26] style consists of only three main parts, known in some schools as ten ('heaven'), chi ('earth'), and jin ('human'). It is a simple style that is designed to show the beauty and uniqueness of the plant itself. Formalisation of the nageire style for use in the Japanese alcove resulted in the formal shoka style.

- In moribana (盛花, 'piled-up flowers'), flowers are arranged in a shallow vase or suiban, compote vessel, or basket, and secured on a kenzan or pointed needle holders, also known as metal frogs.

- In the jiyūka (自由花, 'free flowers')[27] style, creative design of flower arranging is emphasised, with any material permissible for use, including non-flower materials. In the 20th century, with the advent of modernism, the three schools of ikebana partially gave way to what is commonly known in Japan as "Free Style".

- Kyoto Ikebana artist Hayato Nishiyama says he enjoys designs with just a single flower, "to help people concentrate, to help them focus on seeing the beauty of an individual."[28]

Gallery

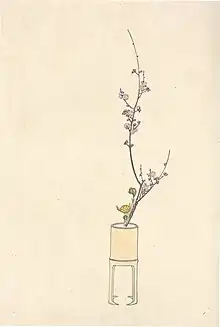

Traditional shōka

Traditional shōka Nageire of the Banmi Shofu-ryū school

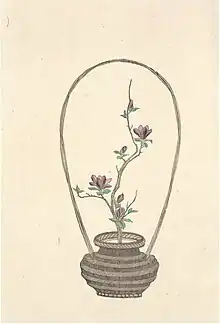

Nageire of the Banmi Shofu-ryū school Jiyūka freestyle arrangement

Jiyūka freestyle arrangement

Vessels

The receptacles used in flower arranging come in a large variety. They are traditionally considered not only beautiful in form, material, and design but are made to suit the use to which they will be put, so that a flower can always be placed in an appropriate receptacle, and probably in one especially designed for that particular sort of flower.[29]

The thing the Japanese most seek in a vase's shape is what will best prolong the life of flowers. For this reason, vases are wide open at the mouth, for, unlike in Western flower arranging, they do not depend upon the vase itself to hold flowers in position, believing that the oxygen entering through the neck opening is as necessary to the plant as the oxygen it receives directly from the water; thus, the water remains sweet much longer than in small-necked vases.[29]

There are many ideas connected with these receptacles. For instance, hanging vases came into use through the idea that flowers presented by an esteemed friend should not be placed where they could be looked down upon, so they were raised and hung. In hanging bamboo vases, the large, round surface on top is supposed to represent the moon, and the hole for the nail a star. The cut, or opening, below the top is called fukumuki, the 'wind drawing through a place'.[29]

Besides offering variety in the form of receptacles, the low, flat vases, more used in summer than winter, make it possible to arrange plants of bulbous and water growth in natural positions.[29]

As for the colour of the vases, the soft pastel shades are common, and bronze vases are especially popular. To the Japanese, the colour bronze seems most like mother earth, and therefore best suited to enhance the beauty of flowers.[29]

Bamboo, in its simplicity of line and neutral colour, makes a charming vase, but one of solid bamboo is not practical in some countries outside of Japan, where the dryness of the weather causes it to split. Baskets made from bamboo reeds, with their soft brown shades, provide a pleasing contrast to the varied tints of the flowers, and are practical in any climate.[29]

Not to be overlooked is the tiny hanging vase found in the simple peasant home – some curious root picked up at no cost and fashioned into a shape suitable to hold a single flower or vine. Such vases can be made with little effort by anyone and can find place nearly anywhere.[29]

In popular culture

- Ikebana is taught in schools. It has also featured in manga, anime and been shown on television.

- In Magic-kyun! Renaissance, the main character Aigasaki Kohana practices ikebana, just like her mother before her.[30]

- The shōjo manga Zig Zag focuses on a boy named Takaaki Asakura (nicknamed "Taiyou" (the sun)) and his affection for flowers.[31]

- In Girls und Panzer one of the main protagonists Isuzu Hana's central theme and hobby is ikebana. She combines her passion for it with tanks. A limited special edition vase in the shape of a tank was made by a Kasama ware kiln that was seen in the anime.[32][33][34]

- In 1957 the film director and grand master of the Sōgetsu-ryū school of Ikebana Hiroshi Teshigahara made the movie titled Ikebana, which describes his school.[35]

- Flower and Sword, released in 2017, tells the story of the development of ikebana during the Sengoku period in the 16th century. Directed by Tetsuo Shinohara, it was based on a novel by Tadashi Onitsuka.[36] Masters and their assistants of the Ikenobō school were involved in creating the various rikka, shoka, and suna-no-mono arrangements for the movie.[37]

See also

References

- ↑ "Ikebana International". www.ikebanahq.org. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Definition of IKEBANA". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017.

- ↑ The Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Charles E. Tuttle Company, ISBN 0-8048-0408-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 "History of Ikebana – IKENOBO ORIGIN OF IKEBANA". www.ikenobo.jp. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Averill, Mary. "Chapter I". Japanese flower arrangement. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Sojo, Toba. "English: A drawing of priests caricatured as animals". Archived from the original on 8 August 2017 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ System, Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users. "JAANUS / zashikikazari 座敷飾". www.aisf.or.jp. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "History of Ikebana – IKENOBO ORIGIN OF IKEBANA". www.ikenobo.jp. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016.

- ↑ "tatebana – Japanese art style". Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "Ikebana International". Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "Ikebana International". www.ikebanahq.org. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016.

- ↑ TEDx Talks (14 April 2015). "Ikebana ~Beyond Japanese art of flower~ – Yuki Tsuji – TEDxShimizu". Archived from the original on 11 November 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Needleman, Deborah (6 November 2017). "The Rise of Modern Ikebana". The New York Times Style Magazine. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ↑ "Ikebana – See the Universe in a Single Flower – Magnifissance". 6 April 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ↑ "Ikebana". 17 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017.

- ↑ Marcia Gay Harden. The Seasons of My Mother: A Memoir of Love, Family, and Flowers. Atria Books. 2018. ISBN 978-1501135705

- ↑ "Beverly Harden obituary (1937–2018) – Kingsland, TX – The Washington Post". Legacy.com.

- ↑ "Marcia Gay Harden on the Impact of Her Mother's Alzheimer's Diagnosis | InStyle".

- ↑ "Past Presidents – Ikebana International Chapter No. 1 Washington, D.C." 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Averill, Mary. "Chapter XXII". Japanese flower arrangement. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Kubo, keiko (2013). "introduction". Keiko's Ikebana: A Contemporary Approach to the Traditional Japanese Art of Flower Arranging. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0600-0. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Averill, Mary. "Chapter II". Japanese flower arrangement. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ "立花正風体、立花新風体とは|いけばなの根源 華道家元池坊". www.ikenobo.jp. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017.

- ↑ "ikebana-flowers.com". Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "砂の物とは – コトバンク". Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "生花正風体、生花新風体とは|いけばなの根源 華道家元池坊". www.ikenobo.jp. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017.

- ↑ "自由花とは|いけばなの根源 華道家元池坊". www.ikenobo.jp. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017.

- ↑ "Beauty of Ikebana Arrangements: Learn From A Master from Japan". 31 August 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Averill, Mary. "Chapter XX". Japanese flower arrangement. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ "First Impressions Digest – Touken Ranbu: Hanamaru, Magic-Kyun! Renaissance, Chi's Sweet Home 2016 – Lost in Anime". 3 October 2016.

- ↑ "Zig·Zag GN 1-2 – Review – Anime News Network". 10 August 2023.

- ↑ "ガルパンがまた想像の斜め上のグッズ作るwwww五十鈴流家元公認 笠間焼戦車型花器!|やらおん!".

- ↑ "Girls & Panzer Tank Vase is Appropriately Elegant – Interest – Anime News Network". 10 August 2023.

- ↑ "WoT「インストーラ付きガルパンスペシャルパック9.6」配信開始!|ガールズ&パンツァー最終章 公式サイト". 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "Ikebana". 15 May 1957. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017 – via www.imdb.com.

- ↑ "Flower and Sword". 3 June 2017. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017 – via www.imdb.com.

- ↑ "いけばな|映画『花戦さ』オフィシャルサイト". 映画『花戦さ』オフィシャルサイト. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017.

Further reading

- Ember, M., & Ember, C. R. (2001). Countries and their Cultures. New York Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved 30 July 2008, from NetLibrary (UMUC Database) .

- Kubo, Keiko (2006). Keiko's Ikebana: A Contemporary Approach to the Traditional Japanese Art of Flower Arranging. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3651-7.

- Leaman, Oliver, ed. (2013). "Archived copy". Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy. London and New York: Taylor & Francis Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-86253-0. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- Okakura, Kakuzō (1906). "Flowers". The Illustrated Book of Tea. London and New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Zamperini Pucci, Evi (1973). Davidson, Georgie (ed.). Japanese Flower Arranging. London: Orbis Book. ISBN 978-0-85613-139-4.

- Ohi, Minobu; Ikenobō, Sen'ei; Ohara, Hōun; Teshigahara, Sōfu (1996). Steere, William C. (ed.). Flower Arrangement: The Ikebana Way. Tokyo: Shufunotomo. ISBN 978-4079700818.

- Satō, Shōzō (1968). The Art of Arranging Flowers: A Complete Guide to Japanese Ikebana. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-0194-0.

- Ingelaere-Brandt, Mit; Van Moerbeke, Katrien (2015). Poetical Ikebana. Oostkamp: Stichting Kunstboek. ISBN 978-9058565198.

- Conder, Josiah (1899). The Floral Art of Japan. Tokyo: Kelly and Walsh, Ltd.

- Averill, Mary (1913). Japanese Flower Arrangement. New York: John Lane Company.