Montgomery County, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| County of Montgomery[1] | |

Clockwise: Downtown Bethesda, Spring Street in Silver Spring, Billy Goat B Trail, rural Darnestown, Rockville town center, Great Falls on the Potomac River. | |

| Nickname: "MoCo" | |

| Motto: French: Gardez Bien (English: Watch Well) | |

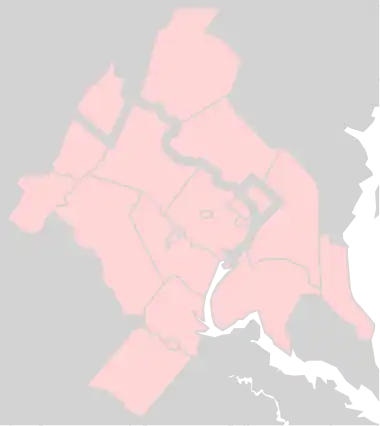

Location in the U.S. state of Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°08′11″N 77°12′15″W / 39.13638°N 77.20424°W[2] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maryland |

| Seat | Rockville |

| Largest community | Germantown |

| Founded | September 6, 1776[3][4] |

| Named for | Richard Montgomery |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Marc Elrich (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 506.91 sq mi (1,312.89 km2) |

| • Land | 493.11 sq mi (1,277.15 km2) |

| • Water | 13.80 sq mi (35.74 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 1,062,061 |

| • Density | 2,153.80/sq mi (831.59/km2) |

| Demonyms | Montgomery Countyan, MoCoite |

| Gross Domestic Product | |

| • Total | US$93.746 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern [EST]) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 20812–20918 |

| Area codes | |

| Congressional districts | 4th, 6th, 8th |

| Website | www |

Montgomery County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 census, the county's population was 1,062,061, increasing by 9.3% from 2010.[6] The county seat is Rockville and Germantown is the most populous place in the county.[7] The county is adjoined to Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, and is part of the Washington metropolitan area and the Washington–Baltimore combined statistical area. Most of the county's residents live in Silver Spring, Bethesda, and the incorporated cities of Rockville and Gaithersburg.[N 1]

The average household income in Montgomery County is the 20th-highest among U.S. counties as of 2020.[8][9][10]

The county has the highest percentage (29.2%) of residents over 25 years of age who hold post-graduate degrees.[11] Like other counties in the Washington metropolitan area, the county has several U.S. government offices, scientific research and learning centers, and business campuses.[12][13]

Etymology

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

The Maryland state legislature named Montgomery County after Richard Montgomery; the county was created from lands that had at one point or another been part of Frederick County.[14] On September 6, 1776,[3] Thomas Sprigg Wootton from Rockville, Maryland, introduced legislation, while serving at the Maryland Constitutional Convention, to create lower Frederick County as Montgomery County. The name, Montgomery County, along with the founding of Washington County, Maryland, after George Washington, was the first time in American history that counties and provinces in the Thirteen Colonies were not named after British referents.

The name use of Montgomery and Washington County were seen as further defiance to Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. The county's nickname of "MoCo" is derived from "Montgomery County".[15][16]

The county's motto, adopted in 1976, is "Gardez Bien", a French phrase meaning "Watch Well". The county's motto is also the motto of its namesake's family.[17][18]

History

Prior to 1688, the first tract of land in what is now Montgomery County was granted by Charles I in a charter to the first Lord Baltimore, the head of the Calvert family. The county's creation was a focus of Thomas S. Wootton who, on August 31, 1776, introduced a measure to form a new county from Frederick County, Maryland to aid area residents in simplifying their business affairs. The measure passed, creating the new political entity of Montgomery County in what was then the colonial-era Province of Maryland.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 507 square miles (1,310 km2), of which 491 square miles (1,270 km2) is land and 16 square miles (41 km2) (3.1%) is water.[20] Montgomery County lies entirely inside the Piedmont plateau. The topography is generally rolling. Elevations range from a low of near sea level along the Potomac River to about 875 feet in the northernmost portion of the county north of Damascus. Relief between valley bottoms and hilltops is several hundred feet.

When Montgomery County was created in 1776, its boundaries were defined as "beginning at the east side of the mouth of Rock Creek on Potowmac river [sic], and running with the said river to the mouth of Monocacy, then with a straight line to Par's spring, from thence with the lines of the county to the beginning".[4]

The county's boundary forms a sliver of land at the far northern tip of the county that is several miles long and averages less than 200 yards wide. In fact, a single house on Lakeview Drive and its yard is sectioned by this sliver into three portions, each separately contained within Montgomery, Frederick and Howard Counties. These jurisdictions and Carroll County meet at a single point at Parr's Spring on Parr's Ridge.

Adjacent counties

- Frederick County (northwest)

- Carroll County (north)

- Howard County (northeast)

- Prince George's County (southeast)

- Washington, D.C. (south)

- Fairfax County, Virginia (southwest)

- Loudoun County, Virginia (west)

National protected areas

- Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park (part)

- Clara Barton National Historic Site

- George Washington Memorial Parkway (part)

Climate

Montgomery County lies within the northern portions of the humid subtropical climate. It has four distinct seasons, including hot, humid summers and cool winters.

Precipitation is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, with an average of 43 inches (110 cm) of rainfall.[21] Thunderstorms are common during the summer months, and account for the majority of the average 35 days with thunder per year. Heavy precipitation is most common in summer thunderstorms, but drought periods are more likely during these months because summer precipitation is more variable than winter.

The mean annual temperature is 55 °F (13 °C). The average summer (June–July–August) afternoon maximum is about 85 °F (29 °C) while the morning minimums average 66 °F (19 °C). In winter (December–January–February), these averages are 44 °F (7 °C) and 28 °F (−2 °C). Extreme heat waves can raise readings to around and slightly above 100 °F (38 °C), and arctic blasts can drop lows to −10 °F (−23 °C) to 0 °F (−18 °C). For Rockville, the record high is 105 °F (41 °C) in 1954, while the record low is −13 °F (−25 °C).[21]

Lower elevations in the south, such as Silver Spring, receive an average of 17.5 inches (44 cm) of snowfall per year.[22] Higher elevations in the north, such as Damascus,[23] receive an average of 21.3 inches (54 cm) of snowfall per year.[24] During a particularly snowy winter, Damascus received 79 inches (200 cm) during the 2009–2010 season.[25]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 18,003 | — | |

| 1800 | 15,058 | −16.4% | |

| 1810 | 17,980 | 19.4% | |

| 1820 | 16,400 | −8.8% | |

| 1830 | 19,816 | 20.8% | |

| 1840 | 15,456 | −22.0% | |

| 1850 | 15,860 | 2.6% | |

| 1860 | 18,322 | 15.5% | |

| 1870 | 20,563 | 12.2% | |

| 1880 | 24,759 | 20.4% | |

| 1890 | 27,185 | 9.8% | |

| 1900 | 30,451 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 32,089 | 5.4% | |

| 1920 | 34,921 | 8.8% | |

| 1930 | 49,206 | 40.9% | |

| 1940 | 83,912 | 70.5% | |

| 1950 | 164,401 | 95.9% | |

| 1960 | 340,928 | 107.4% | |

| 1970 | 522,809 | 53.3% | |

| 1980 | 579,053 | 10.8% | |

| 1990 | 757,027 | 30.7% | |

| 2000 | 873,341 | 15.4% | |

| 2010 | 971,777 | 11.3% | |

| 2020 | 1,062,061 | 9.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] 1790–1960[27] 1900–1990[28] 1990–2000[29] 2010[30] 2020[31] | |||

Since the 1970s, the county has had in place a Moderately Priced Dwelling Unit (MPDU) zoning plan that requires developers to include affordable housing in any new residential developments that they construct in the county. The goal is to create socioeconomically mixed neighborhoods and schools so the rich and poor are not isolated in separate parts of the county. Developers who provide for more than the minimum amount of MPDUs are rewarded with permission to increase the density of their developments, which allows them to build more housing and generate more revenue. Montgomery County was one of the first counties in the U.S. to adopt such a plan, but many other areas have since followed suit.

Montgomery County is by far one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse counties in the United States; four of the ten most culturally diverse cities and towns in the U.S. are in Montgomery County: Gaithersburg, ranking second; Germantown, ranking third; Silver Spring, ranking fourth; and Rockville, ranking ninth. Gaithersburg, Germantown, and Silver Spring all rank as more culturally diverse than New York City, San Jose, and Oakland.[32][33] Maryland overall is one of six minority-majority states, and the only minority-majority state on the East Coast.[34]

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[30] | Pop 2020[31] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 478,765 | 430,980 | 49.27% | 40.58% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 161,689 | 192,714 | 16.64% | 18.15% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,580 | 1,377 | 0.16% | 0.13% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 134,677 | 162,472 | 13.86% | 15.30% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 427 | 440 | 0.04% | 0.04% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 3,617 | 8,589 | 0.37% | 0.81% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 25,624 | 48,080 | 2.64% | 4.53% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 165,398 | 217,409 | 17.02% | 20.47% |

| Total | 971,777 | 1,062,061 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 971,777 people, 357,086 households, and 244,898 families living in the county.[35][36] The population density was 1,978.2 inhabitants per square mile (763.8/km2). There were 375,905 housing units at an average density of 765.2 per square mile (295.4/km2).[37] The racial makeup of the county was 57.5% White, 17.2% Black or African American, 13.9% Asian, 0.4% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 7.0% from other races, and 4.0% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 17.0% of the population.[35] In terms of ancestry, 10.7% were German, 9.6% were Irish, 7.9% were English, 4.9% were Italian, 3.5% were Russian, 3.1% were Polish, 2.9% were American and 2% were French.[38] People of Central American descent made up 8.1% of Montgomery County, with Salvadoran Americans constituting 5.4% of the county's population. Over 52,000 people of Salvadoran descent lived in Montgomery County, with Salvadoran Americans comprising approximately 32% of the county's Hispanic and Latino population. People of South American descent make up 3.8% of the county, with Peruvian Americans being the largest South American community, constituting 1.2% of the county's population.[39]

Of the 357,086 households, 35.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.4% were married couples living together, 11.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 31.4% were non-families, and 25.0% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.22. The median age was 38.5 years.[35]

The median income for a household in the county was $93,373 and the median income for a family was $111,737. Males had a median income of $71,841 versus $55,431 for females. The per capita income for the county was $47,310. About 4.0% of families and 6.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.2% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those age 65 or over.[40]

2000 census

As of the 2000 United States census, there were 873,058 people living in the county. The racial makeup of the county was 65.0% white, 15.1% Black or African American, 11.3% Asian, 0.3% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 5.0% from other races, and 3.5% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 11.5% of the population.[41]

There were 324,565 households, of which 35% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.2% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.9% were non-families. Of all households, 24.4% were made up of individuals, and 7.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.19.

25.4% of the population was under the age of 18, 6.9% from 18 to 24, 32.3% from 25 to 44, 24.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.1 males.

In 2000, there were 334,632 housing units at an average density of 675 per square mile (261/km2).

Montgomery County has the tenth-highest median household income in the United States, and the second highest in the state after Howard County as of 2011. The median household income in 2007 was $89,284 and the median family income was $106,093. Males had a median income of $66,415 versus $52,134 for females. The per capita income for the county was $43,073. About 3.3% of families and 4.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.6% of those under age 18 and 4.6% of those age 65 or over.

2014 estimates

The United States Census Bureau estimated the county's population was 1,030,447 as of 2014.[42] If it were a city, it would be the tenth-most-populous city in the U.S. after San Jose, California and Austin, Texas.

The ethnic makeup of the county was estimated to be the following in 2013:[42]

- 62.6% White (47.0% Non-Hispanic White)

- 18.6% Black

- 14.9% Asian

- 0.7% Native American

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 3.1% Two or more races

In addition, 18.3% were Hispanic or Latino, of any race.[42]

People who were born on continent of Africa are 6% of the county's total residents. The plurality of these were born in Ethiopia.[43] People from China are the fastest-growing immigrant population in the county; people from Ethiopia are the county's second-fastest-growing immigrant population.[43]

2016 estimates

The United States Census Bureau estimated the county's population as 1,043,863 as of 2016.[44]

The race and Hispanic original of the county's residents was estimated to be the following as of 2016:[44]

- 60.9% White (44.7% Non-Hispanic White)

- 19.5% Black

- 15.5% Asian

- 0.7% Native American

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 3.4% Two or more races

In addition, 19.1% were Hispanic or Latino, of any race.[44]

Of residents age 25 or older, 91.2% have graduated high school, and 57.1% had a bachelor's degree.[44]

Of the county's population, 32.6% were born outside the United States.[45]

44,718 veterans lived in the county in 2016.[44]

Of residents age 5 or older, 39.8% spoke a language other than English at home in 2016.[44]

2018 estimates

As of July 1, 2018 The United States Census Bureau estimates the population of the county to be 1,052,567 residents.[46]

The race and Hispanic origin of the county's residents are estimated to be:[46]

- 60.2% White (43.4% Non-Hispanic White) (9.1% German, 8.3% Irish, 6.3% English, 4.3% Italian, 3.7% American, 2.9% Polish, 2.8% Russian)[47]

- 19.9% African-American or Black (1.5% Ethiopian)[47]

- 19.9% Hispanic or Latino (6.80% Salvadoran, 1.71% Mexican, 1.24% Peruvian, 1.22% Guatemalan, 1.06% Honduran, 0.92% Colombian, 0.85% Puerto Rican, 0.70% Dominican)[47]

- 15.6% Asian (4.10% Chinese, 3.68% Indian, 1.62% Korean, 1.42% Vietnamese, 1.22% Filipino, 0.43% Pakistani, 0.31% Japanese, 0.26% Taiwanese, 0.21% Sri Lankan)[47]

- 3.4% Two or more races

- 0.7% American Indian or Alaskan Native

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

The age of the county's residents are estimated to be:[46]

- 6.3% Persons under 5 years

- 23.3% Persons under 18 years

- 15.5% Persons 65 years and over.

An estimated 51.6% of the population is female.

The number of housing units is estimated to be 390,664.

Religion

Of Montgomery County's residents, 14% are Catholic, 5% are Baptist, 3% are Methodist, 1% are Presbyterian, 1% are Episcopalian, 1% are part of the Latter Day Saint movement, 1% are Lutheran, 6% are of another Christian faith, 3% are Jewish, 1% follows Islam, and 1% are of an eastern faith.[48] Overall, 41% of the county's residents are affiliated with a religion.[48]

Montgomery County has the largest Jewish population in the state of Maryland, accounting for 45% of Maryland Jews. According to the Berman Jewish DataBank, Montgomery County has a Jewish population of 105,400 people, around 10% of the county's population.[49] The Washington metropolitan area, with 295,500 Jews, has become the third-largest Jewish population in the United States.[50]

Economy

Montgomery County is an important business and research center. It is the epicenter for biotechnology in the Mid-Atlantic region. Montgomery County, as third largest biotechnology cluster in the U.S., holds a large cluster and companies of large corporate size within the state. Biomedical research is carried out by institutions including Johns Hopkins University's Montgomery County Campus (JHU MCC), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Federal government agencies in Montgomery County engaged in related work include the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Many large firms are based in the county, including Coventry Health Care, Lockheed Martin, Marriott International, Host Hotels & Resorts, Travel Channel, Ritz-Carlton, Robert Louis Johnson Companies (RLJ Companies), Choice Hotels, MedImmune, TV One, BAE Systems Inc., Hughes Network Systems and GEICO.

Other U.S. federal government agencies based in the county include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Downtown Bethesda and Silver Spring are the largest urban business hubs in the county; combined, they rival many major city cores.

Top employers

According to the county's comprehensive annual financial reports, the top employers by number of employees in the county are the following. "NR" indicates the employer was not ranked among the top ten employers that year.

| Employer | Employees (2021)[51][lower-alpha 1] |

Employees (2014)[52] |

Employees (2011)[53] |

Employees (2005)[52] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | 27,500 | 28,500 | 29,700 | 38,800 |

| Montgomery County Public Schools | 27,500 | 25,429 | 22,016 | 20,987 |

| Montgomery County Government | 12,500 | 10,815 | 8,849 | 8,272 |

| U.S. Department of Defense | 7,500 | 12,000 | 12,690 | 13,800 |

| Adventist Healthcare | 7,500 | 4,900 | 5,310 | 6,000 |

| Holy Cross Hospital of Silver Spring | 3,750 | 3,400 | NR | NR |

| Marriott International Administrative Services | 3,750 | 4,700 | 5,441 | NR |

| Montgomery College | 3,750 | 3,632 | NR | NR |

| GEICO | 3,750 | NR | NR | NR |

| U.S. Department of Commerce | 3,750 | 5,500 | 8,250 | 6,200 |

| Lockheed Martin | NR | 4,000 | 4,745 | 3,900 |

| Nuclear Regulatory Commission | NR | 3,840 | NR | NR |

| Giant | NR | NR | 3,842 | 4,900 |

| Verizon | NR | NR | 3,292 | 4,700 |

| Chevy Chase Bank | NR | NR | NR | 4,700 |

- ↑ In 2021, number of employees was given as a range. The figure shown in this table is the average of the range given.

Politics and government

Montgomery County Council | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | 3 consecutive terms |

| History | |

| Founded | 1948 |

| Preceded by | Montgomery County Board of Commissioners |

| Leadership | |

Council President | |

Council Vice President | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 11 |

| |

Political groups | Majority (11)

|

| Committees |

|

Length of term | Full council elected every 4 years |

| Authority | Article I, Charter of Montgomery County |

| Salary |

|

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post | |

First election | November 3, 1948 |

Last election | November 8, 2022 |

Next election | November 3, 2026 |

| Redistricting | Recommendations by the legislature-appointed commission, approval by legislature. |

| Motto | |

| French: Gardez Bien (English: Watch Well) | |

| Meeting place | |

| Stella B. Werner Council Office Building | |

| Website | |

| Council Website | |

| Constitution | |

| Charter[55] | |

| Rules | |

| Rules of Proceduce[56] | |

Montgomery County was granted a charter form of government in 1948.

The present County Executive/County Council form of government of Montgomery County dates to November 1968 when the voters changed the form of government from a County Commission/County Manager system, as provided in the original 1948 home rule Charter.

The Montgomery County government had a surplus of $654 million for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2021.[51]

County executives

The office of the county executive was established in 1970. The first executive was James P. Gleason. The current executive is Marc Elrich, who was sworn in for his first term on December 3, 2018.[57]

| Position | Name | Party | Hometown | Term | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | James Gleason | Republican | 1970–1978 | ||

| 2nd | Charles Gilchrist | Democratic | 1978–1986 | ||

| 3rd | Sidney Kramer | Democratic | 1986–1990 | ||

| 4th | Neal Potter | Democratic | 1990–1994 | ||

| 5th | Doug Duncan | Democratic | Rockville | 1994–2006 | |

| 6th | Ike Leggett | Democratic | Burtonsville | 2006–2018 | |

| 7th | Marc Elrich | Democratic | Takoma Park | 2018– | |

Legislative body

The County Council is the legislative branch of Montgomery County. It has eleven members who serve four-year terms. All are elected at the same time by the voters of Montgomery County.[58][59] As of January 2023, all 11 members on the council are Democrats. The council meets weekly at the county seat of Rockville—the 6th Floor of the Stella B. Werner Council Office Building.[60][61]

The members of the County Council as of 2023 are:[62]

| Position | Name | Affiliation | District | Neighborhoods | First Elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vice President | Andrew Friedson | Democratic | 1 | Potomac, Bethesda, Chevy Chase | 2018 | |

| Member | Marilyn Balcombe | Democratic | 2 | Germantown, Clarksburg, Darnestown, Poolesville | 2022 | |

| Member | Sidney A. Katz | Democratic | 3 | Gaithersburg, Rockville | 2014 | |

| Member | Kate Stewart | Democratic | 4 | Downtown Silver Spring, Takoma Park | 2022 | |

| Member | Kristin Mink | Democratic | 5 | Burtonsville, Four Corners, Cloverly | 2022 | |

| Member | Natali Fani-González | Democratic | 6 | Wheaton, Glenmont, Aspen Hill, Derwood, Forest Glen Park | 2022 | |

| Member | Dawn Luedtke | Democratic | 7 | Damascus, Ashton, Laytonsville, Olney, Montgomery Village | 2022 | |

| Member | Gabe Albornoz | Democratic | At-Large | Entire County | 2018 | |

| President | Evan Glass | Democratic | At-Large | Entire County | 2018 | |

| Member | Will Jawando | Democratic | At-Large | Entire County | 2018 | |

| Member | Laurie-Anne Sayles | Democratic | At-Large | Entire County | 2022 | |

The most recent Republican serving on the Montgomery County Council, Howard A. Denis of District 1 (Potomac/Bethesda), lost re-election in 2006. Since then, all Council members have been Democrats.

Law enforcement

County police

The Montgomery County Police Department (MCPD) provides the full spectrum of policing services to the entire county. It was founded in 1922 and is headquartered in Gaithersburg, Maryland. It consists of around 1,300 sworn officers and 650 support personnel, split into 6 districts throughout the county.[63] The department also provides assistance to other nearby departments, such as the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia and the Prince George's County Police Department, if requested.

County sheriff's office

The Montgomery County Sheriff's Office (MCSO) is a nationally accredited U.S. law enforcement agency and acts as the enforcement arm of the courts in the county. All of its deputy sheriffs are fully certified law enforcement officials with full authority of arrest. The office was created in July 1777 and is the oldest law enforcement agency in Montgomery County.[64] It is headquartered in Rockville, Maryland.[65] It was nationally accredited in 1995, the first county sheriff's office in Maryland to be so. The MCSO has authorized over 165 employees consisting of sworn law enforcement officers and civilian support staff.[66] The office is headed by the sheriff, who has been elected every four years since the 1920s. The current Sheriff is Maxwell C. Uy (D), elected in 2022. Uy is the 62nd Sheriff and the first Asian American to hold that office.[67]

Other agencies

Several cities including Rockville and Gaithersburg maintain their own police departments to complement MCPD. Maryland State Police patrol the Beltway and I-270, and they assist county and city police in investigation of some major crimes.

Budget

Montgomery County has a budget of $2.3 billion. Approximately $1.48 billion are invested in Montgomery County Public Schools and $128 million in Montgomery College.[68]

Bi-county agencies

Montgomery and Prince George's counties share a bi-county planning and parks agency in the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC) and a public bi-county water and sewer utility in the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC).

LGBTIQ+ bill of rights

In October 2020, the Montgomery County Council unanimously passed an ordinance that implemented an LGBTIQ+ bill of rights.[69][70][71]

Liquor control

Montgomery County is an alcoholic beverage control county. Beer and wine may also be sold in private stores.

History

Until 1964, only three restaurants in the county had liquor licenses to serve liquor by the drink.[72] The county stopped issuing liquor licenses to all other restaurants under a law that had existed since Prohibition.[73]

Following a voter referendum,[74] restaurants and bars could apply for county permits to sell liquor by the drink.[73] The dry towns of Kensington, Poolesville, and Takoma Park were allowed to keep their own bans in place.[73]

Anchor Inn in Wheaton was the first establishment to serve liquor in the county under the new law.[72]

Other elected positions

There are 24 judges of the Circuit Court for Montgomery County, who are appointed by the Governor and elected by the voters to 15 year terms. James A. Bonifant has served as the County Administrative Judge since 2021. Karen A. Bushell (D) was appointed as Clerk of the Circuit Court in 2021, and was elected to a full term in 2022. Joseph M. Griffin (D) has served as the Register of Wills since 1998.[75] John J. McCarthy (D) has served as the State's Attorney since 2007.[76]

State representation

In the Maryland House of Delegates, Montgomery County is in districts 9A, represented by Chao Wu and Natalie Ziegler; 14, represented by Bernice Mireku-North, Pamela E. Queen, and Anne Kaiser; 15, represented by David Fraser-Hidalgo, Lily Qi, and Linda Foley; 16, represented by Sarah Siddiqui Wolek, Sara Love, and Marc Korman; 17, represented by Joe Vogel, Julie Palakovich Carr, and Ryan Spiegel; 18, represented by Emily Shetty, Jared Solomon, and Aaron Kaufman; 19, represented by Jheanelle Wilkins, Lorig Charkoudian, and David Moon; and 39, represented by Gabriel Acevero, Lesley Lopez, and W. Gregory Wims.

In the Maryland Senate, Montgomery County is in districts 9, represented by Katie Fry Hester; 14, represented by Craig Zucker; 15, represented by Brian Feldman; 16, represented by Ariana Kelly; 17, represented by Cheryl Kagan; 18, represented by Jeff Waldstreicher; 19, represented by Benjamin F. Kramer; and 20, represented by William C. Smith Jr.

Federal representation

In the 118th Congress, Montgomery County is represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by Glenn Ivey (D) of the 4th district, David Trone (D) of the 6th district, and Jamie Raskin (D) of the 8th district.

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of May 2023[77] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 410,756 | 60.48% | |||

| Republican | 96,704 | 14.24% | |||

| Independents and unaffiliated | 171,679 | 25.28% | |||

| Total | 679,139 | 100.00% | |||

Mongomery County is one of the most consistently Democratic counties in Maryland. Before 1928, the County never voted Republican. In total, it has only voted Republican 8 times. The Democratic presidential candidate has won Montgomery County in every presidential election since 1988. In 2020, Donald Trump turned in the worst showing for a Republican in 152 years, not even managing to reach 20% of the vote.[78]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 101,222 | 18.96% | 419,569 | 78.61% | 12,952 | 2.43% |

| 2016 | 92,704 | 19.36% | 357,837 | 74.72% | 28,332 | 5.92% |

| 2012 | 123,353 | 27.05% | 323,400 | 70.92% | 9,239 | 2.03% |

| 2008 | 118,608 | 27.00% | 314,444 | 71.58% | 6,209 | 1.41% |

| 2004 | 136,334 | 32.83% | 273,936 | 65.97% | 4,955 | 1.19% |

| 2000 | 124,580 | 33.52% | 232,453 | 62.54% | 14,655 | 3.94% |

| 1996 | 117,730 | 35.15% | 198,807 | 59.36% | 18,361 | 5.48% |

| 1992 | 119,705 | 33.01% | 199,757 | 55.09% | 43,151 | 11.90% |

| 1988 | 154,191 | 48.05% | 165,187 | 51.48% | 1,518 | 0.47% |

| 1984 | 146,924 | 50.00% | 146,036 | 49.69% | 910 | 0.31% |

| 1980 | 125,515 | 47.16% | 105,822 | 39.76% | 34,814 | 13.08% |

| 1976 | 122,674 | 48.34% | 131,098 | 51.66% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1972 | 133,090 | 56.50% | 100,228 | 42.55% | 2,239 | 0.95% |

| 1968 | 84,651 | 44.23% | 92,026 | 48.08% | 14,726 | 7.69% |

| 1964 | 52,554 | 33.76% | 103,113 | 66.24% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 62,679 | 48.70% | 66,025 | 51.30% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 56,501 | 57.01% | 42,606 | 42.99% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 47,805 | 62.37% | 28,381 | 37.03% | 467 | 0.61% |

| 1948 | 23,174 | 60.34% | 14,336 | 37.33% | 897 | 2.34% |

| 1944 | 20,400 | 57.10% | 15,324 | 42.90% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 13,831 | 46.85% | 15,177 | 51.41% | 513 | 1.74% |

| 1936 | 10,133 | 43.06% | 13,246 | 56.29% | 153 | 0.65% |

| 1932 | 5,698 | 36.15% | 9,882 | 62.69% | 183 | 1.16% |

| 1928 | 9,318 | 57.74% | 6,739 | 41.76% | 82 | 0.51% |

| 1924 | 5,675 | 44.01% | 6,639 | 51.49% | 580 | 4.50% |

| 1920 | 5,948 | 47.96% | 6,277 | 50.61% | 177 | 1.43% |

| 1916 | 2,913 | 42.50% | 3,805 | 55.52% | 136 | 1.98% |

| 1912 | 1,675 | 26.84% | 3,501 | 56.10% | 1,065 | 17.06% |

| 1908 | 2,805 | 44.70% | 3,351 | 53.40% | 119 | 1.90% |

| 1904 | 2,711 | 46.09% | 3,082 | 52.40% | 89 | 1.51% |

| 1900 | 3,354 | 46.90% | 3,677 | 51.42% | 120 | 1.68% |

| 1896 | 3,219 | 47.02% | 3,456 | 50.48% | 171 | 2.50% |

| 1892 | 2,584 | 41.98% | 3,383 | 54.96% | 188 | 3.05% |

Transportation

Roads

_from_the_overpass_for_West_Gude_Drive_in_Rockville%252C_Montgomery_County%252C_Maryland.jpg.webp)

Poor transportation was a hindrance for Montgomery County's farmers who wanted to transport their crops to market in the early 18th century. Montgomery County's first roads, often barely adequate, were built by the 18th century.

One early road connected Frederick and Georgetown. There was a road that connected Georgetown and the mouth of the Monocacy River. Plans to continue the road to Cumberland did not come to fruition. Another road connected the Montgomery County Courthouse with Sandy Spring and Baltimore, and one other road connected the courthouse with Bladensburg and Annapolis.[79][80]: 52–54 : 75–83

The county's first turnpike was chartered in 1806, but its construction began in 1817. In 1828, the turnpike was completed, running from Georgetown to Rockville. It was the first paved road in Montgomery County.[79][80]: 75–83

In 1849, the Seventh Street Turnpike (now called Georgia Avenue) was extended from Washington to Brookeville. The Colesville–Ashton Turnpike was built in 1870 (now parts of Colesville Road, Columbia Pike, and New Hampshire Avenue).[80]: 75–83

The United States Army Corps of Engineers built the Washington Aqueduct between 1853 and 1864, to supply water from Great Falls to Washington. The aqueduct was covered in 1875, and it became known as Conduit Road. The Union Arch Bridge, which carries the aqueduct across Cabin John Creek, was the longest single-arch bridge in the world at the time it was completed in 1864. The road is now named MacArthur Boulevard.[79][80]: 75–83

Major Highways and Roads

Bus

Montgomery County operates its own bus public transit system, known as Ride On.[81] Major routes closer to its rail service area are also covered by WMATA's Metrobus service.[82]

The county began building a bus rapid transit (BRT) system along US 29 in 2018. The system has been providing service between Silver Spring and Burtonsville since 2020; more routes are planned.[83][84]

The Corridor Cities Transitway is a proposed BRT line that would provide an extension of the Red Line corridor from Gaithersburg to Germantown, and eventually to Frederick County.[85]

Rail

Montgomery County is served by three passenger rail systems, with a fourth line under construction.

Amtrak, the U.S. national passenger rail system, operates its Capitol Limited to Rockville, between Washington Union Station and Chicago Union Station.

The Brunswick line of the MARC commuter rail system makes stops at Silver Spring, Kensington, Garrett Park, Rockville, Washington Grove, Gaithersburg, Metropolitan Grove, Germantown, Boyds, Barnesville, and Dickerson, where the line splits into its Frederick and Martinsburg branches.

Both suburban arms of the Red Line of the Washington Metro serve Montgomery County. It follows the CSX right of way to the west, roughly paralleling Route 355 from Friendship Heights to Shady Grove. The eastern side runs between the two tracks of the CSX right of way from Washington Union Station to Silver Spring, and roughly parallels Georgia Avenue, from Silver Spring to Glenmont.

The Purple Line, a light rail system, is currently under construction and is scheduled to open in 2026.[86] The line will run in a generally east-west direction, connecting Montgomery and Prince George's Counties near the Beltway, with 21 stations. The Purple Line will connect directly with four Metro stations, MARC trains and Amtrak.[87]

Air

The Montgomery County Airpark (FAA GAI, ICAO KGAI), a general aviation facility in Gaithersburg, is the major airport in the county. Davis Airport (FAA Identifier W50), a privately owned airstrip, is located in Laytonsville on Hawkins Creamery Road.[88] Commercial air service is provided at the nearby Ronald Reagan Washington National, Washington Dulles International, and BWI Airports.

Education

Education in the county is provided by Montgomery County Public Schools, Montgomery College and other institutions.

Montgomery County Public Schools

Elementary and secondary public schools are operated by the Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS). The county public school system is the largest school district in Maryland, serving about 162,000 students with 13,000 teachers and 10,000 support staff. The public school system operating budget for Fiscal Year 2019 is $2.6 billion (~$2.95 billion in 2022).[89]

MCPS operates under the jurisdiction of an elected Board of Education. Its current members are:[90]

| Name | District | Term Ends |

|---|---|---|

| Brenda Wolff | District 5 | 2026 |

| Karla Silvestre | At-Large, President | 2026 |

| Grace Rivera-Oven | District 1 | 2026 |

| Shebra L. Evans | District 4, Vice President | 2024 |

| Lynne Harris | At-Large | 2024 |

| Julie Yang | District 3 | 2026 |

| Rebecca Smondrowski | District 2 | 2024 |

| Sami Saeed | Student Member | 2024 |

| Monifa McKnight | Superintendent | 2026 |

MCPS conducted its first 'data deletion week' in 2019, purging its databases of unnecessary student information.[91] Parents said they hoped to shield children from being held accountable in adulthood for youthful mistakes, as well as to guard them from exploitation by what one parent termed "the student data surveillance industrial complex".The district also requires tech companies to annually delete data they collect on schoolchildren. In December 2019 it said GoGuardian had sent formal certification that it had deleted its data, but the district was still waiting for confirmation from Google.[92]

Montgomery College

The county is also served by Montgomery College, a public, open access community college that has a budget of US$315 million for FY2020. The county has no public university of its own, but the state university system does operate a facility called Universities at Shady Grove in Rockville that provides access to baccalaureate and Master's level programs from several of the state's public universities.

Montgomery County Public Libraries

The Montgomery County Public Libraries (MCPL) system includes 23 individual libraries, and had a budget $38 million (~$46.1 million in 2022) for 2015.

Culture

Religion

Montgomery County is religiously diverse. In 2010, Montgomery County's population, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives, was 13% Catholic, 5% Baptist, 4% Evangelical Protestant, 3% Jewish, 3% Methodist/Pietist, 2% Adventist, 2% Presbyterian, 1% Episcopalian/Anglican, 1% Mormon, 1% Muslim, 1% Lutheran, 1% Eastern Orthodox, 1% Pentecostal, 1% Buddhist, and 1% Hindu.[93][N 2]

Montgomery County is the most religiously diverse county in the US outside of New York City. A 2020 census by the Public Religion Research Institute (unconnected to the official US census) calculates a religious diversity score of 0.880 for Montgomery County, where 1 represents complete diversity (each religious group of equal size) and 0 a total lack of diversity. Only two other counties in the US have higher diversity scores than Montgomery County, both in urban New York.[94]

The Seventh-day Adventist Church maintains its General Conference headquarters in Silver Spring in Montgomery County.[95]

Sports

The county is home to the National Women's Soccer League team Washington Spirit, a professional soccer team that played its home games at the Maryland SoccerPlex sports complex in Boyds.[96] In 2021, the Spirit will play its seven home games at Audi Field, in Washington, D.C., and five home games at Segra Field in Leesburg, Virginia.[97] Starting in 2022, the team will work to maximize the number of games played at Audi Field.

Bethesda's Congressional Country Club has hosted four Major Championships, including three playings of the U.S. Open, most recently in 2011 which was won by Rory McIlroy. The Club also hosts the Quicken Loans National, an annual event on the PGA Tour which benefits the Tiger Woods Foundation. Previously, neighboring TPC at Avenel hosted the Booz Allen Classic.

The award-winning Members Club at Four Streams is located on a former farm in Beallsville, Maryland.

The Bethesda Big Train, Rockville Express, and Silver Spring–Takoma Thunderbolts all play college level wooden bat baseball in the Cal Ripken Collegiate Baseball League.

Montgomery County is home of the Montgomery County Swim League, a youth (ages 4–18) competitive swimming league composed of ninety teams based at community pools throughout the county.

The King Farm Park in Rockville, open and accessible 24/7 without cost, provides a first-class 16-station Bankshot Playcourt, the Home Court for the Rockville based Bankshot Sports Organization advocating "Total-mix diversity based on Universal Design." Hundreds of communities provide Bankshot Playcourts mainstreaming differently-able participants in community sports. Bankshot basketball Playcourts are also at Montrose park, the JCC among other locations.

Montgomery County Agricultural Fair

Since 1949 the Montgomery County Agricultural Fair, the largest in the state, showcases farm life in the county. The week long event offers family events, carnival rides, live animals, entertainment and food. Visitors can also view entries of canned and baked goods, clothing, quilts and produce from local county farmers.[98]

Sister cities

Montgomery County maintains sister city agreements with:[99]

Communities

Gaithersburg

Gaithersburg Rockville

Rockville.jpg.webp) Takoma Park

Takoma Park Montgomery County map

Montgomery County map

Cities

- Gaithersburg

- Rockville (county seat)

- Takoma Park

Towns

Villages

Special Tax Districts

Occupying a middle ground between incorporated and unincorporated areas are Special Tax Districts, quasi-municipal unincorporated areas created by legislation passed by either the Maryland General Assembly or the county.[100] The Special Tax Districts generally have limited purposes, such as providing some municipal services or improvements to drainage or street lighting.[100] Special Tax Districts lack home rule authority and must petition their cognizant governmental entity for changes affecting the authority of the district. The four incorporated villages of Montgomery County and the town of Chevy Chase View were originally established as Special Tax Districts. Four Special Tax Districts remain in the county:

Census-designated places

Bethesda

Bethesda Germantown

Germantown Silver Spring

Silver Spring

Unincorporated areas are also considered as towns by many people and listed in many collections of towns, but they lack local government. Various organizations, such as the United States Census Bureau, the United States Postal Service, and local chambers of commerce, define the communities they wish to recognize differently, and since they are not incorporated, their boundaries have no official status outside the organizations in question. The Census Bureau recognizes the following census-designated places in the county:

- Ashton-Sandy Spring

- Aspen Hill

- Bethesda

- Brookmont

- Burtonsville

- Cabin John

- Calverton (partly in Prince George's County)

- Chevy Chase

- Clarksburg

- Cloverly

- Colesville

- Damascus

- Darnestown

- Fairland

- Forest Glen

- Four Corners

- Germantown

- Glenmont

- Hillandale (partly in Prince George's County)

- Kemp Mill

- Layhill

- Leisure World

- Montgomery Village

- North Bethesda

- North Potomac

- Olney

- Potomac

- Redland

- Silver Spring

- South Kensington

- Travilah

- White Oak

- Wheaton

Unincorporated communities

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Although Rockville is the most populous incorporated city in Montgomery County, Germantown, an unincorporated census-designated place, is the most populous locale in the county.

- ↑ These figures count adherents, meaning all full members, their children, and others who regularly attend services. In all of Montgomery County, 40% of the population is adherent to any particular religion.

References

- ↑ "Chapter 66. 'Village of Friendship Heights.'". Montgomery County Charter. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

County of Montgomery

- ↑ "Montgomery County". GeoNames.org. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- 1 2 "Montgomery County Centennial: An Old-Fashioned Maryland Reunion". The Baltimore Sun. September 7, 1876. p. 1. ProQuest 534282014.

- 1 2 Maryland. Convention (1836). Proceedings of the Conventions of the providence of Maryland, held at the city of Annapolis, in 1774, 1775, & 1776. Baltimore, Md.; Annapolis, Md.: Baltimore, James Lucas & E. K. Deaver; Annapolis, Jonas Green. p. 242. hdl:loc.gdc/scd0001.00117695347. LCCN 10012042. OCLC 3425542. OL 7018977M.

Resolved, That after the first day of October next, such part of the said county of Frederick as is contained within the bounds and limits following, to wit : beginning at the east side of the mouth of Rock creek on Potowmac river, and running with the said river to the mouth of Monocacy, then with a straight line to Par's spring, from thence with the lines of the county to the beginning, shall be and is hereby erected into a new county by the name of Montgomery county.

- ↑ "Gross Domestic Product by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022" (PDF). www.bea.gov. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

- ↑ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ↑ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "Maryland by Place – GCT-PH1-R. Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density (geographies ranked by total population): 2000". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ↑ Morello, Carol; Mellnick, Ted (September 19, 2012). "Seven of nation's 10 most affluent counties are in Washington region". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Complete List: America's Richest Counties" Archived April 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, February 2, 2008

- ↑ "Montgomery County QuickFacts" Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, September 9, 2009

- ↑ Bureau, U. S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ Archived February 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, February 26, 2015

- ↑ Archived February 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Montgomery County Chamber of Commerce, February 26, 2015

- ↑ Tom (November 7, 2012). "Why Is It Named Montgomery County?". Ghosts of DC. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ↑ Rapid Transit - Montgomery County, MD. "Get On Board BRT - Vote Now!". Archived from the original on March 26, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Council, Montgomery (November 15, 2016). "@CoUnTy_ExEc talks about his mission to make #MoCo one of the most welcoming places on earth. #CommunityMatterspic.twitter.com/EJuLFi2NAz". Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ Clan Montgomery Society (June 14, 2008). "Montgomery Motto". Clan Montgomery Symbols. Clan Montgomery Society. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

"Garde" (pronounced gard-uh) or "Gardez" (pronounced garday) means "watch", in the sense of "look out" or "on guard". "Bien" (pronounced bee-ann) means "good" to give the overall meaning of "Watch Well".

- ↑ "Places From the Past". Montgomery County Historic Sites. Silver Spring, Maryland: Montgomery County Planning Department. January 26, 2012. Archived from the original on April 30, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

Gardez Bien, adopted in 1976 as the county motto, means to guard well or take good care

- ↑ "Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- 1 2 "Intellicast - Rockville Historic Weather Averages in Maryland (20857)". Accuweather. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Intellicast - Silver Spring Historic Weather Averages in Maryland (20901)". Accuweather. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ↑ Samenow, Jason (March 18, 2014). "Astonishing snow totals this winter in upper Montgomery County: nearly 70 inches". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Intellicast - Damascus Historic Weather Averages in Maryland (20872)". Accuweather. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ↑ Wheatley, Katie; Livingston, Ian (May 9, 2014). "How much snow fell in your backyard? Mapping the 2013-2014 winter snow totals in the Mid-Atlantic". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decades". US Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- 1 2 "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Montgomery County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau.

- 1 2 "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Montgomery County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ Hedgpeth, Dana. "Four places in Maryland rank among the nation's most ethnically diverse, study says". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ↑ "4 Maryland cities in top 10 for most culturally diverse cities in U.S., according to WalletHub". FOX 5 DC. February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race". data.census.gov. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. DP-1. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ "2010 Census Summary File One (SF1) - Maryland Population Characteristics, Montgomery County Archived February 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". United States Census Bureau via Maryland State Data Center.

- ↑ "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States 2006-2010; American Community Survey; 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. DP02. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Selected Economic Characteristics – 2006-2010; American Community Survey; 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. DP03. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Population of Montgomery County, MD - Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts - CensusViewer". censusviewer.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Montgomery County, Maryland". State & County Quickfacts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- 1 2 "African Community Archived December 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". Office of Community Partnerships. Montgomery County Government. 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "QuickFacts: Montgomery County, Maryland Archived February 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Montgomery County, Maryland Archived December 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Quick Facts. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Montgomery County, Maryland". www.census.gov. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- 1 2 "Montgomery County, Maryland: Religion Archived October 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". Sperling's BestPlaces. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ "United States Jewish Population, 2018" (PDF). Berman Jewish DataBank. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ↑ "D.C. area's Jewish population is booming: Now the third largest in the nation, report says". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- 1 2 "Montgomery County, Maryland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ending June 30, 2021" (PDF). Montgomery County, Maryland. December 17, 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2022.

- 1 2 "Montgomery County, Maryland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ending June 30, 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Montgomery County, Maryland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ending June 30, 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2012.

- ↑ "About Montgomery County Council". Montgomery County Council. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Charter of Montgomery County, Maryland". American Legal Publishing. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ↑ "Rules of Procedure - Montgomery County". American Legal Publishing. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ↑ Barrios, Jennifer (December 3, 2018). "Elrich promises change, 'more just society,' as he becomes Montgomery executive". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ↑ "About Montgomery County Council". www.montgomerycountymd.gov. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Montgomery County, Maryland – Government, Legislative Branch". msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ↑ "Members at a Glance – Montgomery County Council".

- ↑ Official website

- ↑ "Council Districts Map". montgomerycountymd.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ↑ "About Us Page, Montgomery County Police Department, Montgomery County, MD". montgomerycountymd.gov. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Montgomery County Sheriff's Office". www.mcsheriff.com.

- ↑ "Montgomery County Sheriff's Office". June 20, 2002. Archived from the original on June 20, 2002.

- ↑ "Montgomery County Sheriff's Office, MD:". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008.

- ↑ Morse, Dan (January 4, 2023). "New Montgomery sheriff takes on staffing shortages, other challenges". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ↑ "Montgomery County Spending". Montgomery County MD. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Montgomery County Council unanimously passes LGBTQ Bill of Rights". Washington Blade. October 8, 2020.

- ↑ Pollak, Suzanne (October 7, 2020). "Council Enacts LGBTQ Bill of Rights". Montgomery Community Media.

- ↑ "Montgomery County Passes LGBTQ Bill of Rights". NBC4 Washington. October 7, 2020.

- 1 2 Kendrick, Thomas R. "New Montgomery Liquor Permits Start 6 Restaurants Serving Drinks Archived May 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". The Washington Post. December 8, 1964. p. B1.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Bart. "County's Liquor Laws Liberalized Archived May 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". The Washington Post. November 8, 1964. p. B1.

- ↑ Kendrick, Thomas R. "D.C., Maryland Party Aides Ponder Vote Results: Liquor Question in Montgomery Depends on Absentee Ballots Archived May 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". The Washington Post. November 5, 1964. p. B1.

- ↑ "Montgomery County, Maryland - Government, Judicial Branch". msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ↑ "John J. McCarthy, State's Attorney, Montgomery County, Maryland". msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ↑ "Summary of Voter Activity Report" (PDF). Maryland State Board of Elections. October 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- 1 2 Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Sween, Jane C.; Offutt, William (1999). Montgomery County: Centuries of Change. American Historical Press. ISBN 1-892724-05-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Boyd, T.H.S. (1879). The History of Montgomery County, Maryland from Its Earliest Settlement in 1650 to 1879 (PDF). Clarksburg, MD: Regional Publishing Company.

- ↑ "Ride On Routes and Schedules". Rockville, MD: Montgomery County Department of Transportation (MCDOT). Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Metrobus Routes in Montgomery County". Transit Services. MCDOT. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ↑ Schere, Dan (October 25, 2018). "County Officials Break Ground on 14-Mile Bus Rapid Transit Line". Bethesda Beat. Bethesda Magazine. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ↑ "US 29 Project". Bus Rapid Transit Project. MCDOT. April 2, 2018. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Corridor Cities Transitway". Baltimore, MD: Maryland Transit Administration. Archived from the original on December 27, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ↑ Shaver, Katherine (January 26, 2022). "Md. board approves $3.4 billion contract to complete Purple Line". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Project Overview". Maryland Purple Line. Riverdale, MD: Maryland Transit Administration. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Davis Airport". Airnav.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ↑ "About MCPS". Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Public Schools. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- ↑ "MCPS School Board Members". MCPS. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCPS Student 'Data Deletion Week' Begins". Bethseda magazine. August 19, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ↑ "Tech companies monitor schoolkids across America. These parents are making them delete the data". The Guardian. December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ↑ "County Membership Report: Montgomery County, Maryland: Religious Traditions, 2010". Association of Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014.

- ↑ Public Religion Research Institute. The 2020 Census of American Religion (Report). p. 21. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ↑ "Contact". Seventh-Day Adventist Church. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Maryland Soccerplex History". Maryland Soccer Foundation. May 6, 2000. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Washington Spirit extends partnership with D.C. United and Loudoun United FC to host four matches at Audi Field in addition to four games at Segra Field in 2020". D.C. United. November 12, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ↑ "About Us - The Montgomery County Agricultural Fair". www.mcagfair.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ "OUR SISTER CITIES | Montgomery County Sister Cities". Sistercities. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- 1 2 "Special Taxing Districts and Regional Agencies". 1998 Legislative Handbook. General Assembly of Maryland. 1998. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008.

External links

Geographic data related to Montgomery County, Maryland at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Montgomery County, Maryland at OpenStreetMap- Official website

- "Census Incorporated Places and Census Designated Places in Montgomery County, as shown by Maryland Department of Planning" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- "Montgomery County: Independent City, County Subdivisions, and Other Places" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2010. p. E-15. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2012.

- "Census Tract Reference Map" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022.

- "List of sheriffs, Montgomery County, Maryland". Maryland State Archives. Annapolis, Maryland: State of Maryland. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.