Shqiptarët | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 7 to 10 million[1][2][3][4][5] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Other regions | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Albanian | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Majority: Sunnism[lower-alpha 1] · Bektashism · Non-denominational Minority: Catholicism[lower-alpha 2] (Latin Church · Eastern Rites Albanian Greek-Catholic Church · Italo-Albanian Church) · Eastern Orthodoxy[lower-alpha 3] (Albanian Orthodox Church · Albanian American Orthodox Church) · Protestantism (Albanian Protestant Church · Kosovan Protestant Church) Other: Irreligion | |||||||||||||||||||||

a 502,546 Albanian citizens, an additional 43,751 Kosovo Albanians, 260,000 Arbëreshë people and 169,644 Albanians who have acquired the Italian citizenship[8][9][64][65] b Albanians are not recognized as a minority in Turkey. However approximately 500,000 people are reported to profess an Albanian identity. Of those with full or partial Albanian ancestry and others who have adopted Turkish language, culture and identity their number is estimated at 1,300,000–5,000,000 many whom do not speak Albanian.[58] c The estimation contains Kosovo Albanians. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

The Albanians (/ælˈbeɪniənz, ɔːl-/ a(w)l-BAY-nee-ənz; Albanian: Shqiptarët, pronounced [ʃcipˈtaɾət]) are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language.[66] They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia as well as in Croatia, Greece, Italy and Turkey. They also constitute a large diaspora with several communities established across Europe, the Americas and Oceania.

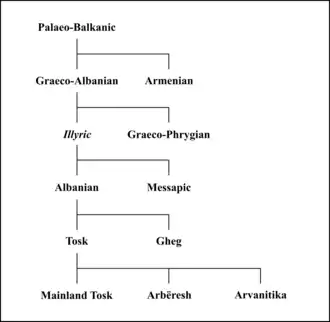

Albanians have Paleo-Balkanic origins. Exclusively attributing these origins to the Illyrians, Thracians or other Paleo-Balkan people is still a matter of debate among historians and ethnologists.

The first mention of the ethnonym Albanoi occurred in the 2nd century AD by Ptolemy describing an Illyrian tribe who lived around present-day central Albania.[67][68] The first certain reference to Albanians as an ethnic group comes from 11th century chronicler Michael Attaleiates who describes them as living in the theme of Dyrrhachium.

The Shkumbin River roughly demarcates the Albanian language between Gheg and Tosk dialects. Christianity in Albania was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome until the 8th century AD. Then, dioceses in Albania were transferred to the patriarchate of Constantinople. In 1054, after the Great Schism, the north gradually became identified with Roman Catholicism and the south with Eastern Orthodoxy. In 1190 Albanians established the Principality of Arbanon in central Albania with the capital in Krujë.

The Albanian diaspora has its roots in migration from the Middle Ages initially across Southern Europe and eventually across wider Europe and the New World. Between the 13th and 18th centuries, sizeable numbers migrated to escape various social, economic or political difficulties.[lower-alpha 4] One population, the Arvanites, settled in Southern Greece between the 13th and 16th centuries. Another population, the Arbëreshë, settled across Sicily and Southern Italy between the 11th and 16th centuries.[70] Smaller populations such as the Arbanasi settled in Southern Croatia and pockets of Southern Ukraine in the 18th century.[73][74]

By the 15th century, the expanding Ottoman Empire overpowered the Balkan Peninsula, but faced successful rebellion and resistance by the League of Lezhë, a union of Albanian principalities led by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. By the 17th and 18th centuries, a substantial number of Albanians converted to Islam, which offered them equal opportunities and advancement within the Ottoman Empire.[75] Thereafter, Albanians attained significant positions and culturally contributed to the broader Muslim world.[76] Innumerable officials and soldiers of the Ottoman State were of Albanian origin, including more than 40 Grand Viziers,[77] and under the Köprülü, in particular, the Ottoman Empire reached its greatest territorial extension.[78] Between the second half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century Albanian Pashaliks were established by Kara Mahmud pasha of Scutari, Ali pasha of Yanina, and Ahmet Kurt pasha of Berat, while the Albanian wālī Muhammad Ali established a dynasty that ruled over Egypt and Sudan until the middle of the 20th century, a period in which Albanians formed a substantial community in Egypt.

During the 19th century, cultural developments, widely attributed to Albanians having gathered both spiritual and intellectual strength, conclusively led to the Albanian Renaissance. In 1912 during the Balkan Wars, Albanians declared the independence of their country. The demarcation of the new Albanian state was established following the Treaty of Bucharest and left about half of the ethnic Albanian population outside of its borders, partitioned between Greece, Montenegro and Serbia.[79] After the Second World War up until the Revolutions of 1991, Albania was governed by a communist government under Enver Hoxha where Albania became largely isolated from the rest of Europe. In neighbouring Yugoslavia, Albanians underwent periods of discrimination and systematic oppression that concluded with the War of Kosovo and eventually with Kosovar independence.

Ethnonym

The Albanians (Albanian: Shqiptarët) and their country Albania (Albanian: Shqipëria) have been identified by many ethnonyms. The most common native ethnonym is "Shqiptar", plural "Shqiptarë"; the name "Albanians" (Byzantine Greek: Albanoi/Arbanitai/Arbanites; Latin: Albanenses/Arbanenses) was used in medieval documents and gradually entered European Languages from which other similar derivative names emerged,[80] many of which were or still are in use,[81][82][83] such as English "Albanians"; Italian "Albanesi"; German "Albaner"; Greek "Arvanites", "Alvanitis" (Αλβανίτης) plural: "Alvanites" (Αλβανίτες), "Alvanos" (Αλβανός) plural: "Alvanoi" (Αλβανοί); Turkish "Arnaut", "Arnavut"; South Slavic languages "Arbanasi" (Арбанаси), "Albanci" (Албанци); Aromanian "Arbinesh" and so on.[lower-alpha 5]

The term "Albanoi" (Αλβανοί) is first encountered on the works of Ptolemy (200-118 BCE)[67] also is encountered twice in the works of Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, and the term "Arvanitai" (Αρβανίται) is used once by the same author. He referred to the "Albanoi" as having taken part in a revolt against the Byzantine Empire in 1043, and to the "Arbanitai" as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium (modern Durrës).[87] These references have been disputed as to whether they refer to the people of Albania.[87][88] Historian E. Vranoussi believes that these "Albanoi" were Normans from Sicily. She also notes that the same term (as "Albani") in medieval Latin meant "foreigners".[89]

The reference to "Arvanitai" from Attaliates regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion around 1078 is undisputed.[90] In later Byzantine usage, the terms "Arbanitai" and "Albanoi" with a range of variants were used interchangeably, while sometimes the same groups were also called by the classicising name Illyrians.[91][92][93] The first reference to the Albanian language dates to the latter 13th century (around 1285).[94]

The national ethnonym Albanian and its variants are derived from Albanoi, first mentioned as an Illyrian tribe in the 2nd century CE by Ptolemy with their centre at the city of Albanopolis, located in modern-day central Albania, somewhere in the hinterland of Durrës.[95][81][96][97][98][99] Linguists believe that the alb part in the root word originates from an Indo-European term for a type of mountainous topography, from which other words such as alps are derived.[100] Through the root word alban and its rhotacized equivalents arban, albar, and arbar, the term in Albanian became rendered as Arbëneshë/Arbëreshë for the people and Arbënia/Arbëria for the country.[80][81] The Albanian language was referred to as Arbnisht and Arbërisht.[96] While the exonym Albania for the general region inhabited by the Albanians does have connotations to Classical Antiquity, the Albanian language employs a different ethnonym, with modern Albanians referring to themselves as Shqip(ë)tarë and to their country as Shqipëria.[81] Two etymologies have been proposed for this ethnonym: one, derived from the etymology from the Albanian word for eagle (shqipe, var., shqiponjë).[83] In Albanian folk etymology, this word denotes a bird totem, dating from the times of Skanderbeg as displayed on the Albanian flag.[83][101] The other is within scholarship that connects it to the verb 'to speak' (me shqiptue) from the Latin "excipere".[83] In this instance the Albanian endonym like Slav and others would originally have been a term connoting "those who speak [intelligibly, the same language]".[83] The words Shqipëri and Shqiptar are attested from 14th century onward,[102] but it was only at the end of 17th and beginning of the early 18th centuries that the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëreshë amongst Albanian speakers.[81][102] That era brought about religious and other sociopolitical changes.[81] As such a new and generalised response by Albanians based on ethnic and linguistic consciousness to this new and different Ottoman world emerging around them was a change in ethnonym.[81]

Historical records

Little is known about the Albanian people prior to the 11th century, though a text compiled around the beginning of the 11th century in the Bulgarian language contains a possible reference to them.[103] It is preserved in a manuscript written in the Serbo-Croatian Language traced back to the 17th century but published in the 20th century by Radoslav Grujic. It is a fragment of a once longer text that endeavours to explain the origins of peoples and languages in a question-and-answer form similar to a catechism.

The fragmented manuscript differentiated the world into 72 languages and three religious categories including Christians, half-believers and non-believers. Grujic dated it to the early 11th century and, if this and the identification of the Arbanasi as Albanians are correct, it would be the earliest written document referring to the Balkan Albanians as a people or language group.[103]

It can be seen that there are various languages on earth. Of them, there are five Orthodox languages: Bulgarian, Greek, Syrian, Iberian (Georgian) and Russian. Three of these have Orthodox alphabets: Greek, Bulgarian and Iberian (Georgian). There are twelve languages of half-believers: Alamanians, Franks, Magyars (Hungarians), Indians, Jacobites, Armenians, Saxons, Lechs (Poles), Arbanasi (Albanians), Croatians, Hizi and Germans.

Michael Attaleiates (1022–1080) mentions the term Albanoi twice and the term Arbanitai once. The term Albanoi is used first to describe the groups which rebelled in southern Italy and Sicily against the Byzantines in 1038–40. The second use of the term Albanoi is related to groups which supported the revolt of George Maniakes in 1042 and marched with him throughout the Balkans against the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. The term Arvanitai is used to describe a revolt of Bulgarians (Boulgaroi) and Arbanitai in the theme of Dyrrhachium in 1078–79. It is generally accepted that Arbanitai refers to the ethnonym of medieval Albanians. As such, it is considered to be the first attestation of Albanians as an ethnic group in Byzantine historiography.[104] The use of the term Albanoi in 1038–49 and 1042 as an ethnonym related to Albanians have been a subject of debate. In what has been termed the "Vranoussi-Ducellier debate", Alain Ducellier proposed that both uses of the term referred to medieval Albanians. Era Vranoussi counter-suggested that the first use referred to Normans, while the second didn't have an ethnic connotation necessarily and could be a reference to the Normans as "foreigners" (aubain) in Epirus which Maniakes and his army traversed.[104] This debate has never been resolved.[105] A newer synthesis about the second use of the term Albanoi by Pëllumb Xhufi suggests that the term Albanoi may have referred to Albanians of the specific district of Arbanon, while Arbanitai to Albanians in general regardless of the specific region they inhabited.[106]

Language

The majority of the Albanian people speak the Albanian language which is an independent branch within the Indo-European family of languages. It is a language isolate to any other known living language in Europe and indeed no other language in the world has been conclusively associated to its branch. Its origin remains conclusively unknown but it is believed it has descended from an ancient Paleo-Balkan language.[107]

The Albanian language is spoken by approximately 5 million people throughout the Balkan Peninsula as well as by a more substantial number by communities around the Americas, Europe and Oceania. Numerous variants and dialects of Albanian are used as an official language in Albania, Kosovo and North Macedonia.[108][109][110][111] The language is also spoken in other countries whence it is officially recognised as a minority language in such countries as Croatia, Italy, Montenegro, Romania and Serbia.[112][113][114]

There are two principal dialects of the Albanian language traditionally represented by Gheg and Tosk.[115][116] The ethnogeographical dividing line is traditionally considered to be the Shkumbin river, with Gheg spoken in the north of it and Tosk in the south. Dialects of linguistic minorities spoken in Croatia (Arbanasi and Istrian), Kosovo, Montenegro and northwestern North Macedonia are classified as Gheg, while those spoken in Greece, southwestern North Macedonia and Italy as Tosk.

The Arbëresh and Arvanitika dialects of the Albanian language, are spoken by the Arbëreshë and Arvanites in Southern Italy and Southern Greece, respectively. They retain elements of medieval Albanian vocabulary and pronunciation that are no longer used in modern Albanian; however, both varieties are classified as endangered languages in the UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages.[117][118][119] The Cham dialect is spoken by the Cham Albanians, a community that originates from Chameria in what is currently north-western Greece and southern Albania; the use of the Cham dialect in Greece is declining rapidly, while Cham communities in Albania and the diaspora have preserved it.[120][121][122]

Most of the Albanians in Albania and the Former Yugoslavia are polyglot and have the ability to understand, speak, read, or write a foreign language. As defined by the Institute of Statistics of Albania, 39.9% of the 25 to 64 years old Albanians in Albania are able to use at least one foreign language including English (40%), Italian (27.8%) and Greek (22.9%).[123]

The origin of the Albanian language remains a contentious subject that has given rise to numerous hypotheses. The hypothesis of Albanian being one of the descendant of the Illyrian languages (Messapic language) is based on geography where the languages were spoken however not enough archaeological evidence is left behind to come therefore to a definite conclusion. Another hypothesis associates the Albanian language with the Thracian language. This theory takes exception to the territory, since the language was spoken in an area distinct from Albania, and no significant population movements have been recorded in the period when the shift from one language to the other is supposed to have occurred.[124]

History

Late Antiquity

The Komani-Kruja culture is an archaeological culture attested from late antiquity to the Middle Ages in central and northern Albania, southern Montenegro and similar sites in the western parts of North Macedonia. It consists of settlements usually built below hillforts along the Lezhë (Praevalitana)-Dardania and Via Egnatia road networks which connected the Adriatic coastline with the central Balkan Roman provinces. Its type site is Komani and its fort on the nearby Dalmace hill in the Drin river valley. Kruja and Lezha represent significant sites of the culture. The population of Komani-Kruja represents a local, western Balkan people which was linked to the Roman Justinianic military system of forts. The development of Komani-Kruja is significant for the study of the transition between the classical antiquity population of Albania to the medieval Albanians who were attested in historical records in the 11th century. Winnifrith (2020) recently described this population as the survival of a "Latin-Illyrian" culture which emerged later in historical records as Albanians and Vlachs (Eastern Romance-speaking people). In Winnifrith's narrative, the geographical conditions of northern Albania favored the continuation of the Albanian language in hilly and mountainous areas as opposed to lowland valleys.[125]

Middle Ages

The Albanian people maintain a very chequered and tumultuous history behind them, a fact explained by their geographical position in the Southeast of Europe at the cultural and political crossroad between the east and west. The issue surrounding the origin of the Albanian people has long been debated by historians and linguists for centuries. Many scholars consider the Albanians, in terms of linguistic evidences, the descendants of ancient populations of the Balkan Peninsula, either the Illyrians, Thracians or another Paleo-Balkan group.[126]

The first certain attestation of medieval Albanians as an ethnic group is in Byzantine historiography in the work of Michael Attaleiates (1022–1080).[104] Attaleiates mentions the term Albanoi twice and the term Arbanitai once. The term Albanoi is used first to describe the groups which rebelled in southern Italy and Sicily against the Byzantines in 1038–40. The second use of the term Albanoi is related to groups which supported the revolt of George Maniakes in 1042 and marched with him throughout the Balkans against the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. The term Arvanitai is used to describe a revolt of Bulgarians (Boulgaroi) and Arbanitai in the theme of Dyrrhachium in 1078–79. It is generally accepted that Arbanitai refers to the ethnonym of medieval Albanians. The use of the term Albanoi in 1038–49 and 1042 as an ethnonym related to Albanians have been a subject of debate. In what has been termed the "Ducellier-Vrannousi" debate, Alain Ducellier proposed that both uses of the term referred to medieval Albanians. Era Vrannousi counter-suggested that the first use referred to Normans, while the second didn't have an ethnic connotation necessarily and could be a reference to the Normans as "foreigners" (aubain) in Epirus which Maniakes and his army traversed.[104] The debate has never been resolved.[105] A newer synthesis about the second use of the term Albanoi by Pëllumb Xhufi suggests that the term Albanoi may have referred to Albanians of the specific district of Arbanon, while Arbanitai to Albanians in general regardless of the specific region they inhabited.[106] The name reflects the Albanian endonym Arbër/n + esh which itself derives from the same root as the name of the Albanoi[127]

Historically known as the Arbër or Arbën by the 11th century and onwards, they traditionally inhabited the mountainous area to the west of Lake Ochrida and the upper valley of the Shkumbin river.[128][129] Though it was in 1190 when they established their first independent entity, the Principality of Arbër (Arbanon), with its seat based in Krujë.[130][131] Immediately after the decline of the Progon dynasty in 1216, the principality came under Gregorios Kamonas and next his son-in-law Golem. Finally, the Principality was dissolved in ca. 1255 by the Empire of Nicea followed by an unsuccessful rebellion between 1257 and 1259 supported by the Despotate of Epirus. In the meantime Manfred, King of Sicily profited from the situation and launched an invasion into Albania. His forces, led by Philippe Chinard, captured Durrës, Berat, Vlorë, Spinarizza, their surroundings and the southern coastline of Albania from Vlorë to Butrint.[132] In 1266 after defeating Manfred's forces and killing him, the Treaty of Viterbo of 1267 was signed, with Charles I, King of Sicily acquiring rights on Manfred's dominions in Albania.[133][134] Local noblemen such as Andrea Vrana refused to surrender Manfred's former domains, and in 1271 negotiations were initiated.[135]

In 1272 the Kingdom of Albania was created after a delegation of Albanian noblemen from Durrës signed a treaty declaring union with the Kingdom of Sicily under Charles.[135] Charles soon imposed military rule, new taxes, took sons of Albanian noblemen hostage to ensure loyalty, and confiscated lands for Angevin nobles. This led to discontent among Albanian noblemen, several of whom turned to Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII. In late 1274, Byzantine forces helped by local Albanian noblemen capture Berat and Butrint.[136] Charles' attempt to advance towards Constantinople failed at the Siege of Berat (1280–1281). A Byzantine counteroffensive ensued, which drove the Angevins out of the interior by 1281. The Sicilian Vespers rebellion further weakened the position of Charles, who died in 1285. By the end of the 13th century, most of Albania was under Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos. In 1296 Serbian king Stephen Milutin captured Durrës. In 1299 Andronikos II married his daughter Simonis to Milutin and the lands he had conquered were considered as dowry. In 1302, Philip I, Prince of Taranto, grandson of Charles, claimed his rights on the Albanian kingdom and gained the support of local Albanian Catholics who preferred him over the Orthodox Serbs and Greeks, as well as the support of Pope Benedict XI. In the summer of 1304, the Serbs were expelled from the city of Durrës by the locals who submitted themselves to Angevin rule.[137]

Prominent Albanian leaders during this time were the Thopia family, ruling in an area between the Mat and Shkumbin rivers,[138] and the Muzaka family in the territory between the Shkumbin and Vlorë.[139] In 1279, Gjon I Muzaka, who remained loyal to the Byzantines and resisted Angevin conquest of Albania, was captured by the forces of Charles but later released following pressure from Albanian nobles. The Muzaka family continued to remain loyal to the Byzantines and resisted the expansion of the Serbian Kingdom. In 1335 the head of the family, Andrea II Muzaka, gained the title of Despot and other Muzakas pursued careers in the Byzantine government in Constantinople. Andrea II soon endorsed an anti-Byzantine revolt in his domains between 1335–1341 and formed an alliance with Robert, Prince of Taranto in 1336.[140] In 1336, Serbian king Stefan Dušan captured Durrës, including the territory under the control of the Muzaka family. Although Angevins managed to recapture Durazzo, Dušan continued his expansion, and in the period of 1337–45 he had captured Kanina and Valona in southern Albania.[141] Around 1340 forces of Andrea II defeated the Serbian army at the Pelister mountain.[141] After the death of Stefan Dušan in 1355 the Serbian Empire disintegrated, and Karl Thopia captured Durrës while the Muzaka family of Berat regained control over parts of southeastern Albania and over Kastoria[140][142] that Andrea II captured from Prince Marko after the Battle of Marica in 1371.[143][73]

The kingdom reinforced the influence of Catholicism and the conversion to its rite, not only in the region of Durrës but in other parts of the country.[144] A new wave of Catholic dioceses, churches and monasteries were founded, papal missionaries and a number of different religious orders began spreading into the country. Those who were not Catholic in central and northern Albania converted and a great number of Albanian clerics and monks were present in the Dalmatian Catholic institutions.[145]

Around 1230 the two main centers of Albanian settlements were around Devoll river in what is now central Albania[146] and the other around the region known as Arbanon.[147] Albanian presence in Croatia can be traced back to the beginning of the Late Middle Ages.[148] In this period, there was a significant Albanian community in Ragusa with a number of families of Albanian origin inclusively the Sorgo family who came from the Cape of Rodon in central Albania, across Kotor in eastern Montenegro, to Dalmatia.[149] By the 13th century, Albanian merchants were trading directly with the peoples of the Republic of Ragusa in Dalmatia which increased familiarity between Albanians and Ragusans.[150] The upcoming invasion of Albania by the Ottoman Empire and the death of Skanderbeg caused many Christian Albanians to flee to Dalmatia and surrounding countries.[151]

In the 14th century a number of Albanian principalities were created. These included Principality of Kastrioti, Principality of Dukagjini, Princedom of Albania, and Principality of Gjirokastër. At the beginning of the 15th century these principalities became stronger, especially because of the fall of the Serbian Empire. Some of these principalities were united in 1444 under the anti-Ottoman military alliance called League of Lezha.

Albanians were recruited all over Europe as a light cavalry known as stratioti. The stratioti were pioneers of light cavalry tactics during the 15th century. In the early 16th century heavy cavalry in the European armies was principally remodeled after Albanian stradioti of the Venetian army, Hungarian hussars and German mercenary cavalry units (Schwarzreitern).[152]

Ottoman Empire

Prior to the Ottoman conquest of Albania, the political situation of the Albanian people was characterised by a fragmented conglomeration of scattered kingdoms and principalities such as the Principalities of Arbanon, Kastrioti and Thopia. Before and after the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire continued an extended period of conquest and expansion with its borders going deep into the Southeast Europe. As a consequence thousands of Albanians from Albania, Epirus and Peloponnese escaped to Calabria, Naples, Ragusa and Sicily, whereby others sought protection at the often inaccessible Mountains of Albania.

Under the leadership of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, a former governor of the Ottoman Sanjak of Dibra, a prosperous and longstanding revolution erupted with the formation of the League of Lezhë in 1444 up until the Siege of Shkodër ending in 1479, multiple times defeating the mightiest power of the time led by Sultans Murad II and Mehmed II. Skanderbeg managed to gather several of the Albanian principals, amongst them the Arianitis, Dukagjinis, Zaharias and Thopias, and establish a centralised authority over most of the non-conquered territories and proclaiming himself the Lord of Albania (Dominus Albaniae in Latin).[153] Skanderbeg consistently pursued the aim relentlessly but rather unsuccessfully to create a European coalition against the Ottomans. His unequal fight against them won the esteem of Europe and financial and military aid from the Papacy and Naples, Venice and Ragusa.[154][155][156]

The Albanians, then predominantly Christian, were initially considered as an inferior class of people and as such were subjected to heavy taxes such as the Devshirme system that allowed the state to collect a requisite percentage of Christian adolescents from the Balkans and elsewhere to compose the Janissary.[157] Since the Albanians were seen as strategically important, they made up a significant proportion of the Ottoman military and bureaucracy. They were therefore to be found within the imperial services as vital military and administrative retainers from Egypt to Algeria and the rest of the Maghreb.[158]

In the late 18th century, Ali Pasha Tepelena created the autonomous region of the Pashalik of Yanina within the Ottoman Empire which was never recognised as such by the High Porte. The territory he properly governed incorporated most of southern Albania, Epirus, Thessaly and southwestern Macedonia. During his rule, the town of Janina blossomed into a cultural, political and economic hub for both Albanians and Greeks.

The ultimate goal of Ali Pasha Tepelena seems to have been the establishment of an independent rule in Albania and Epirus.[159] Thus, he obtained control of Arta and took control over the ports of Butrint, Preveza and Vonitsa. He also gained control of the pashaliks of Elbasan, Delvina, Berat and Vlorë. His relations with the High Porte were always tense though he developed and maintained relations with the British, French and Russians and formed alliances with them at various times.[160]

In the 19th century, the Albanian wālī Muhammad Ali established a dynasty that ruled over Egypt and Sudan until the middle of the 20th century.[161] After a brief French invasion led by Napoleon Bonaparte and the Ottomans and Mameluks competing for power there, he managed collectively with his Albanian troops to become the Ottoman viceroy in Egypt.[162] As he revolutionised the military and economic spheres of Egypt, his empire attracted Albanian people contributing to the emergence of the Albanian diaspora in Egypt initially formed by Albanian soldiers and mercenaries.

.jpg.webp)

Islam arrived in the lands of the Albanian people gradually and grew widespread between at least the 17th and 18th centuries.[76] The new religion brought many transformations into Albanian society and henceforth offered them equal opportunities and advancement within the Ottoman Empire.

With the advent of increasing suppression on Catholicism, the Ottomans initially focused their conversions on the Catholic Albanians of the north in the 17th century and followed suit in the 18th century on the Orthodox Albanians of the south.[163][164] At this point, the urban centers of central and southern Albania had largely adopted the religion of the growing Muslim Albanian elite. Many mosques and tekkes were constructed throughout those urban centers and cities such as Berat, Gjirokastër, Korçë and Shkodër started to flourish.[165] In the far north, the spread of Islam was slower due to Catholic Albanian resistance and the inaccessible and rather remote mountainous terrain.[166]

The motives for conversion to Islam are subject to differing interpretations according to scholars depending on the context though the lack of sources does not help when investigating such issues.[76] Reasons included the incentive to escape high taxes levied on non-Muslims subjects, ecclesiastical decay, coercion by Ottoman authorities in times of war, and the privileged legal and social position Muslims within the Ottoman administrative and political machinery had over that of non-Muslims.[167][168][169][170][171][172][173]

As Muslims, the Albanians attained powerful positions in the Ottoman administration including over three dozen Grand Viziers of Albanian origin, among them Zagan Pasha, Bayezid Pasha and members of the Köprülü family, and regional rulers such as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and Ali Pasha of Tepelena. The Ottoman sultans Bayezid II and Mehmed III were both Albanian on their maternal side.[174][175]

Areas such as Albania, western Macedonia, southern Serbia, Kosovo, parts of northern Greece and southern Montenegro in Ottoman sources were referred to as Arnavudluk or Albania.[176][177][178]

Albanian Renaissance

The Albanian Renaissance characterised a period wherein the Albanian people gathered both spiritual and intellectual strength to establish their rights for an independent political and social life, culture and education. By the late 18th century and the early 19th century, its foundation arose within the Albanian communities in Italy and Romania and was frequently linked to the influences of the Romanticism and Enlightenment principles.[180]

Albania was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire for almost five centuries and the Ottoman authorities suppressed any expression of unity or national conscience by the Albanian people. A number of thoroughly intellectual Albanians, among them Naum Veqilharxhi, Girolamo de Rada, Dora d'Istria, Thimi Mitko, Naim and Sami Frashëri, made a conscious effort to awaken feelings of pride and unity among their people by working to develop Albanian literature that would call to mind the rich history and hopes for a more decent future.[181]

The Albanians had poor or often no schools or other institutions in place to protect and preserve their cultural heritage. The need for schools was preached initially by the increasing number of Albanians educated abroad. The Albanian communities in Italy and elsewhere were particularly active in promoting the Albanian cause, especially in education which finally resulted with the foundation of the Mësonjëtorja in Korçë, the first secular school in the Albanian language.

The Turkish yoke had become fixed in the nationalist mythologies and psyches of the people in the Balkans, and their march toward independence quickened. Due to the more substantial of Islamic influence, the Albanians internal social divisions, and the fear that they would lose their Albanian territories to the emerging neighbouring states, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Greece, were among the last peoples in the Balkans to desire division from the Ottoman Empire.[182]

The national awakening as a coherent political movement emerged after the Treaty of San Stefano, according to which Albanian-inhabited territories were to be ceded to the neighbouring states, and focused on preventing that partition.[183][184] It was the impetus for the nation-building movement, which was based more on fear of partition than national identity.[184] Even after the declaration of independence, national identity was fragmented and possibly non-existent in much of the newly proposed country.[184] The state of disunity and fragmentation would remain until the communist period following Second World War, when the communist nation-building project would achieve greater success in nation-building and reach more people than any previous regime, thus creating Albanian national communist identity.[184]

Communism in Albania

Enver Hoxha of the Communist Party of Labour took power in Albania in 1946. Albania established an alliance with the Eastern Bloc which provided Albania with many advantages in the form of economic assistance and military protection from the Western Bloc during the Cold War.

The Albanians experienced a period of several beneficial political and economic changes. The government defended the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Albania, diversified the economy through a programme of industrialisation which led to a higher standard of living and followed improvements in areas such as health, education and infrastructure.[185]

It subsequently followed a period wherein the Albanians lived within an extreme isolation from the rest of the world for the next four decades. By 1967, the established government had officially proclaimed Albania to be the first atheistic state in the world as they beforehand confiscated churches, monasteries and mosques, and any religious expression instantly became grounds for imprisonment.[186]

Protests coinciding with the emerging revolutions of 1989 began to break out in various cities throughout Albania including Shkodër and Tirana which eventually lead to the fall of communism. Significant internal and external migration waves of Albanians to such countries as Greece and Italy followed.

Bunkerisation is arguably the most visible and memorable legacy of communism in Albania. Nearly 175,000 reinforced concrete bunkers were built on strategic locations across Albania's territory including near borders, within towns, on the seashores or mountains.[187] These bunkers were never used for their intended purpose or for sheltered the population from attacks or an invasion by a neighbor. However, they were abandoned after the breakup of communism and have been sometimes reused for a variety of purposes.

Independence of Kosovo

Kosovo declared independence from Serbia on 17 February 2008, after years of strained relations between the Serb and predominantly Albanian population of Kosovo. It has been officially recognised by Australia, Canada, the United States and major European Union countries, while Serbia refuse to recognise Kosovo's independence, claiming it as Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244.

The overwhelming majority of Kosovo's population is ethnically Albanian with nearly 1.7 million people.[188] Their presence as well as in the adjacent regions of Toplica and Morava is recorded since the Middle Ages.[189] As the Serbs expelled many Albanians from the wider Toplica and Morava regions in Southern Serbia, which the 1878 Congress of Berlin had given to the Principality of Serbia, many of them settled in Kosovo.[190][191][192]

After being an integral section of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Kosovo including its Albanian population went through a period of discrimination, economic and political persecution. Rights to use the Albanian language were guaranteed by the constitution of the later formed Socialist Yugoslavia and was widely used in Macedonia and Montenegro prior to the dissolution of Yugoslavia.[193] In 1989, Kosovo lost its status as a federal entity of Yugoslavia with rights similar to those of the six other republics and eventually became part of Serbia and Montenegro.

In 1998, tensions between the Albanian and Serb population of Kosovo culminated in the Kosovo War, which led to the external and internal displacement of hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanians. Serbian paramilitary forces committed war crimes in Kosovo, although the government of Serbia claims that the army was only going after suspected Albanian terrorists. NATO launched a 78-day air campaign in 1999, which eventually led to an end to the war.[194]

Distribution

Balkans

Approximately five million Albanians are geographically distributed across the Balkan Peninsula with about half this number living in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Montenegro as well as to a more lesser extent in Croatia and Serbia. There are also significant Albanian populations in Greece.

Approximately 1.8 million Albanians are concentrated in the partially recognised Republic of Kosovo. They are geographically distributed south of the municipality of North Mitrovica and constitute the overall majority ethnic group of the territory.

In Montenegro, the Albanian population is currently estimated to be around 30,000 forming one of the constituent ethnic minority groups of the country.[19][195] They predominantly live in the coastal region of Montenegro around the municipalities of Ulcinj and Bar but also Tuz and around Plav in the northern region as well as in the capital city of Podgorica in the central region.[19]

.jpg.webp)

In North Macedonia, there are more than approximately 500,000 Albanians constituting the largest ethnic minority group in the country.[197][198] The vast majority of the Albanians are chiefly concentrated around the municipalities of Tetovo and Gostivar in the northwestern region, Struga and Debar in the southwestern region as well as around the capital of Skopje in the central region.

In Croatia, the number of Albanians stands at approximately 17.500 mostly concentrated in the counties of Istria, Split-Dalmatia and most notably in the capital city of Zagreb.[199][112] The Arbanasi people who historically migrated to Bulgaria, Croatia and Ukraine live in scattered communities across Bulgaria, Croatia and Southern Ukraine.[74]

In Serbia, the Albanians are an officially recognised ethnic minority group with a population of around 70,000.[200] They are significantly concentrated in the municipalities of Bujanovac and Preševo in the Pčinja District. In Romania, the number of Albanians is unofficially estimated from 500 to 10,000 mainly distributed in Bucharest. They are recognised as an ethnic minority group and are respectively represented in Parliament of Romania.[201][202]

Italy

The Italian Peninsula across the Adriatic Sea has attracted Albanian people for more than half a millennium often due to its immediate proximity. Albanians in Italy later became important in establishing the fundamentals of the Albanian Renaissance and maintaining the Albanian culture. The Arbëreshë people came sporadically in several small and large cycles initially as Stratioti mercenaries in service of the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily and the Republic of Venice.[203][204][205] Larger migration waves occurred after the death of Skanderbeg and the capture of Krujë and Shkodër by the Ottomans to escape the forthcoming political and religious changes.[206]

Today, Arbëreshë constitute one of the largest ethnolinguistic minority groups and their language is recognized and protected constitutionally under the provisions of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[207][208][209] The total number of Arbëreshës is approximately 260,000 scattered across Sicily, Calabria and Apulia.[70] There are Italian Albanians in the Americas especially in such countries as Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Canada and the United States.

After 1991, a mass migration of Albanians towards Italy occurred.[210] Between 2015 and 2016, the number of Albanian migrants who held legal permits of residence in Italy was numbered to be around 480,000 and 500,000.[210][211] Tuscany, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna represent the regions with the strongest presence of the modern Albanian population in Italy.[210] As of 2022, 433,000 Albanian migrants who held legal permits of residence lived in Italy and were the second largest migrant community in Italy after Romanians.[212] As of 2018, an additional ca. 200,000 Albanian migrants have obtained Italian citizenship (children born in Italy not included).[213]

As of 2012, 41.5% of the Albanian in Italy population were counted as Muslim, 38.9% as Christian including 27.7% as Roman Catholic and 11% as Eastern Orthodox and 17.8% as Irreligious.[214]

Greece

The Arvanites and Albanians of Western Thrace are a group descended from Tosks who migrated to southern and central Greece between the 13th and 16th centuries.[71] They are Greek Orthodox Christians, and though they traditionally speak a dialect of Tosk Albanian known as Arvanitika, they have fully assimilated into the Greek nation and do not identify as Albanians.[72][215][216] Arvanitika is in a state of attrition due to language shift towards Greek and large-scale internal migration to the cities and subsequent intermingling of the population during the 20th century.

The Cham Albanians were a group that formerly inhabited a region of Epirus known as Chameria, nowadays Thesprotia in northwestern Greece. Many Cham Albanians converted to Islam during the Ottoman era. Muslim Chams were expelled from Greece during World War II, by an anti-communist resistance group (EDES). The causes of the expulsion were multifaceted and remain a matter of debate among historians. Different narratives in historiography argue that the causes involved pre-existing Greek policies which targeted the minority and sought its elimination, the Cham collaboration with the Axis forces and local property disputes which were instrumentalized after WWII.[217][218] The estimated number of Cham Albanians expelled from Epirus to Albania and Turkey varies: figures include 14,000, 19,000, 20,000, 25,000 and 30,000.[219][220][221][222][223] According to Cham reports this number should be raised to c. 35,000.[224]

Large-scale migration from Albania to Greece occurred after 1991. During this period, at least 500,000 Albanians have migrated and relocated to Greece. Despite the lack of exact statistics, it is estimated that at least 700,000 Albanians have moved to Greece during the last 25 years. The Albanian government estimates 500,000 Albanians in Greece at the very least without accounting for their children.[12] The 2011 Greece census indicated that Albanians consisted the biggest group of migrants in Greece, numbered roughly 480,000, but taking into consideration the current population of Greece (11 million) and the fact that the census failed to account for illegal foreigners, it was estimated that Albanians consist of 5% of the population (at least 550,000).[13] By 2005, around 600,000 Albanians lived in Greece, forming the largest immigrant community in the country.[225] They are economic migrants whose migration began in 1991, following the collapse of the Socialist People's Republic of Albania. As of 2022, in total, there might have been more than 500,000 Albanian-born migrants and their children who received Greek citizenship over the years.[226] In recent years, many Albanian workers and their families have left Greece in search of better opportunities elsewhere in Europe.[226] As of 2022, there c. 292,000 Albanian immigrants are holders of legal permits to live and work in Greece, down from c. 423,000 in 2021.[227]

Albanians in Greece have a long history of Hellenisation, assimilation and integration.[228][229] Many ethnic Albanians have been naturalised as Greek nationals, others have self-declared as Greek since arrival and a considerable number live and work across both countries seasonally hence the number of Albanians in the country has often fluctuated.[230]

Diaspora

Diaspora based Albanians may self identify as Albanian, use hybrid identification or identify with their nationality, often creating an obstacle in establishing a total figure of the population.[231]

Europe

During the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries, the conflicts in the Balkans and the Kosovo War set in motion large population movements of Albanians to Central, Western and Northern Europe.[232] The gradual collapse of communism in Albania triggered as well a new wave of migration and contributed to the emergence of a new diaspora, mainly in Southern Europe, in such countries as Greece and Italy.[233][234][235]

In Central Europe, there are approximately 200,000 Albanians in Switzerland with the particular concentration in the cantons of Zürich, Basel, Lucerne, Bern and St. Gallen.[41][236] The neighbouring Germany is home to around 250,000 to 300,000 Albanians while in Austria there are around 40,000 to 80,000 Albanians concentrated in the states of Vienna, Styria, Salzburg, Lower and Upper Austria.[39][40][237][238]

In Western Europe, the Albanian population of approximately 10,000 people living in the Benelux countries is in comparison to other regions relatively limited. There are more than 6,000 Albanian people living in Belgium and 2,800 in the nearby Netherlands. The most lesser number of Albanian people in the Benelux region is to be found in Luxembourg with a population of 2,100.[239][45][48]

Within Northern Europe, Sweden possesses the most sizeable population of Albanians in Scandinavia however there is no exact answer to their number in the country. The populations also tend to be lower in Norway, Finland and Denmark with more than 18,000, 10,000 and 8,000 Albanians respectively.[27][28][30] The population of Albanians in the United Kingdom is officially estimated to be around 39,000 whiles in Ireland there are less than 2,500 Albanians.[240][32]

Asia and Africa

The Albanian diaspora in Africa and Asia, in such countries as Egypt, Syria or Turkey, was predominantly formed during the Ottoman period through economic migration and early years of the Republic of Turkey through migration due to sociopolitical discrimination and violence experienced by Albanians in Balkans.[241] In Turkey, the exact numbers of the Albanian population of the country are difficult to correctly estimate. According to a 2008 report, there were approximately 1.300,000 people of Albanian descent living in Turkey.[242] As of that report, more than 500,000 Albanian descendants still recognise their ancestry and or their language, culture and traditions.[243]

There are also other estimates that range from being 3 to 4 million people up to a total of 5 million in number, although most of these are Turkish citizens of either full or partial Albanian ancestry being no longer fluent in Albanian, comparable to the German Americans.[243][244][58] This was due to various degrees of either linguistic and or cultural assimilation occurring amongst the Albanian diaspora in Turkey.[58] Albanians are active in the civic life of Turkey.[243][245]

In Egypt there are 18,000 Albanians, mostly Tosk speakers.[58] Many are descendants of the Janissaries of Muhammad Ali Pasha, an Albanian who became Wāli, and self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan.[58] In addition to the dynasty that he established, a large part of the former Egyptian and Sudanese aristocracy was of Albanian origin.[58] Albanian Sunnis, Bektashis and Orthodox Christians were all represented in this diaspora, whose members at some point included major Renaissance figures (Rilindasit), including Thimi Mitko, Spiro Dine, Andon Zako Çajupi, Milo Duçi, Fan Noli and others who lived in Egypt for a time.[246] With the ascension of Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt and rise of Arab nationalism, the last remnants of Albanian community there were forced to leave.[247] Albanians have been present in Arab countries such as Syria, Lebanon,[246] Iraq, Jordan, and for about five centuries as a legacy of Ottoman Turkish rule.

Americas and Oceania

The first Albanian migration to North America began in the 19th and 20th centuries not long after gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire. However the Arbëreshë people from Southern Italy were the first Albanian people to arrive in the New World, many of them migrating after the wars that accompanied the Risorgimento.[248][249]

Since then several Albanian migration waves have occurred throughout the 20th century as for instance after the Second World War with Albanians mostly from Yugoslavia rather than from Communist Albania, then after the Breakup of Communist Albania in 1990 and finally following the Kosovo War in 1998.[250][251]

The most sizeable Albanian population in the Americas is predominantly to be found in the United States. New York metropolitan area in the State of New York is home to the most sizeable Albanian population of the United States.[252] As of 2017, there are approximately 205,000 Albanians in the country with the main concentration in the states of New York, Michigan, Massachusetts and Illinois.[253][49] The number could be higher counting the Arbëreshë people as well; they are often distinguishable from other Albanian Americans with regard to their Italianized names, nationality and a common religion.[254]

In Canada, there are approximately 39,000 Albanians in the country, including 36,185 Albanians from Albania and 2,870 Albanians from Kosovo, predominantly distributed in a multitude of provinces such as Ontario, Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia.[51] Canada's largest cities such as Toronto, Montreal and Edmonton were besides the United States a major centre of Albanian migration to North America. Toronto is home to around 17,000 Albanians.[255]

Albanian immigration to Australia began in the late 19th century and most took place during the 20th century.[256] People who planned to immigrate chose Australia after the US introduced immigration quotas on southern Europeans.[256] Most were from southern Albania, of Muslim and Orthodox backgrounds and tended to live in Victoria and Queensland, with smaller numbers in Western and Northern Australia.[256][257]

Italy's annexation of Albania marked a difficult time for Albanian Australians as many were thought by Australian authorities to pose a fascist threat.[258] Post-war, the numbers of Albanian immigrants slowed due to immigration restrictions placed by the communist government in Albania.[259]

Albanians from southwestern Yugoslavia (modern North Macedonia) arrived and settled in Melbourne in the 1960s-1970s.[260][261] Other Albanian immigrants from Yugoslavia came from Montenegro and Serbia. The immigrants were mostly Muslims, but also Catholics among them including the relatives of the renowned Albanian nun and missionary Mother Teresa.[256] Albanian refugees from Kosovo settled in Australia following the aftermath of the Kosovo conflict.[256][262]

In the early twenty first century, Victoria has the highest concentration of Albanians and smaller Albanian communities exist in Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland, New South Wales and the Northern Territory.[263][264] In 2016, approximately 4,041 persons resident in Australia identified themselves as having been born in Albania and Kosovo, while 15,901 persons identified themselves as having Albanian ancestry, either alone or in combination with another ancestry.[265]

Albanian migration to New Zealand occurred mid twentieth century following the Second World War.[266][267][268] A small group of Albanian refugees originating mainly from Albania and the rest from Yugoslavian Kosovo and Macedonia settled in Auckland.[268][269][270] During the Kosovo crisis (1999), up to 400 Kosovo Albanian refugees settled in New Zealand.[271][272][273] In the twenty first century, Albanian New Zealanders number 400-500 people and are mainly concentrated in Auckland.[274][270]

Culture

Traditions

Tribal social structure

The Albanian tribes (Albanian: fiset shqiptare) form a historical mode of social organization (farefisní) in Albania and the southwestern Balkans characterized by a common culture, often common patrilineal kinship ties tracing back to one progenitor and shared social ties. The fis (Albanian definite form: fisi; commonly translated as "tribe", also as "clan" or "kin" community) stands at the center of Albanian organization based on kinship relations, a concept which can be found among southern Albanians also with the term farë (Albanian definite form: fara). Inherited from ancient Illyrian social structures, Albanian tribal society emerged in the early Middle Ages as the dominant form of social organization among Albanians.[275][276] It also remained in a less developed system in southern Albania[277] where large feudal estates and later trade and urban centres began to develop at the expense of tribal organization. One of the most particular elements of the Albanian tribal structure is its dependence on the Kanun, a code of Albanian oral customary laws.[275] Most tribes engaged in warfare against external forces like the Ottoman Empire. Some also engaged in limited inter-tribal struggle for the control of resources.[277]

Until the early years of the 20th century, the Albanian tribal society remained largely intact until the rise to power of communist regime in 1944, and is considered as the only example of a tribal social system structured with tribal chiefs and councils, blood feuds and oral customary laws, surviving in Europe until the middle of the 20th century.[277][278][279] Members of the tribes of northern Albania believe their history is based on the notions of resistance and isolationism.[280] Some scholars connect this belief with the concept of "negotiated peripherality". Throughout history the territory northern Albanian tribes occupy has been contested and peripheral so northern Albanian tribes often exploited their position and negotiated their peripherality in profitable ways. This peripheral position also affected their national program which significance and challenges are different from those in southern Albania.[281]

Kanun

The Kanun is a set of Albanian traditional customary laws, which has directed all the aspects of the Albanian tribal society.[282][283] For at least the last five centuries and until today, Albanian customary laws have been kept alive only orally by the tribal elders. The success in preserving them exclusively through oral systems highlights their universal resilience and provides evidence of their likely ancient origins.[284] Strong pre-Christian motifs mixed with motifs from the Christian era reflect the stratification of the Albanian customary law across various historical ages.[285] Over time, Albanian customary laws have undergone their historical development, they have been changed and supplemented with new norms, in accordance with certain requirements of socio-economic development.[286] Besa and nderi (honour) are of major importance in Albanian customary law as the cornerstone of personal and social conduct.[287] The Kanun is based on four pillars – Honour (Albanian: Nderi), Hospitality (Albanian: Mikpritja), Right Conduct (Albanian: Sjellja) and Kin Loyalty (Albanian: Fis).

Besa

An Albanian who says besa once cannot in any way break [his] promise and cannot be unfaithful [to it].

Besa (pledge of honor)[289] is an Albanian cultural precept, usually translated as "faith" or "oath", that means "to keep the promise" and "word of honor".[290] The concept is based upon faithfulness toward one's word in the form of loyalty or as an allegiance guarantee.[291] Besa contains mores toward obligations to the family and a friend, the demand to have internal commitment, loyalty and solidarity when conducting oneself with others and secrecy in relation to outsiders.[291] The besa is also the main element within the concept of the ancestor's will or pledge (amanet) where a demand for faithfulness to a cause is expected in situations that relate to unity, national liberation and independence that transcend a person and generations.[291]

The concept of besa is included in the Kanun, the customary law of the Albanian people.[291] The besa was an important institution within the tribal society of the Albanian tribes,[292] who swore oaths to jointly fight against invaders, and in this aspect the besa served to uphold tribal autonomy.[292] The besa was used toward regulating tribal affairs between and within the Albanian tribes.[293]

Culinary arts

The traditional cuisine of the Albanians is diverse and has been greatly influenced by traditions and their varied environment in the Balkans and turbulent history throughout the course of the centuries.[296] There is a considerable diversity between the Mediterranean and Balkan-influenced cuisines of Albanians in the Western Balkan nations and the Italian and Greek-influenced cuisines of the Arbëreshës and Chams. The enjoyment of food has a high priority in the lives of Albanian peoples especially when celebrating religious festivals such as Ramadan, Eid, Christmas, Easter, Hanukkah or Novruz

Ingredients include many varieties of fruits such as lemons, oranges, figs and olives, herbs such as basil, lavender, mint, oregano, rosemary and thyme and vegetables such as garlic, onion, peppers, potatoes and tomatoes. Albanian peoples who live closer to the Mediterranean Sea, Prespa Lake and Ohrid Lake are able to complement their diet with fish, shellfish and other seafood. Otherwise, lamb is often considered the traditional meat for different religious festivals. Poultry, beef and pork are also in plentiful supply.

Tavë Kosi is a national dish in Albania consisting of garlic lamb and rice baked under a thick, tart veil of yogurt. Fërgesë is another national dish and is made with peppers, tomatoes and cottage cheese. Pite is a baked pastry with a filling of a mixture of spinach and gjizë or mish. Desserts include Flia, consisting of multiple crepe-like layers brushed with crea; petulla, a traditionally fried dough, and Krofne, similar to Berliner.

Visual arts

Painting

.jpg.webp)

The earliest preserved relics of visual arts of the Albanian people are sacred in nature and represented by numerous frescoes, murals and icons which has been created with an admirable use of color and gold. They reveal a wealth of various influences and traditions that converged in the historical lands of the Albanian people throughout the course of the centuries.[297]

The rise of the Byzantines and Ottomans during the Middle Ages was accompanied by a corresponding growth in Christian and Islamic art often apparent in examples of architecture and mosaics throughout Albania.[298] The Albanian Renaissance proved crucial to the emancipation of the modern Albanian culture and saw unprecedented developments in all fields of literature and arts whereas artists sought to return to the ideals of Impressionism and Romanticism.[299][300]

Onufri, founder of the Berat School, Kolë Idromeno, David Selenica, Kostandin Shpataraku and the Zografi Brothers are the most eminent representatives of Albanian art. Albanians in Italy and Croatia have been also active among others the Renaissance influenced artists such as Marco Basaiti, Viktor Karpaçi and Andrea Nikollë Aleksi. In Greece, Eleni Boukouras is noted as being the first great female painter of post independence Greece.

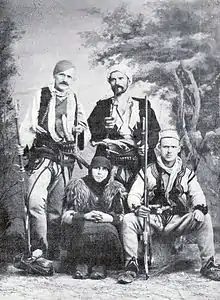

In 1856, Pjetër Marubi arrived in Shkodër and established the first photography museum in Albania and probably the entire Balkans, the Marubi Museum. The collection of 150,000 photographs, captured by the Albanian-Italian Marubi dynasty, offers an ensemble of photographs depicting social rituals, traditional costumes, portraits of Albanian history.

The Kulla, a traditional Albanian dwelling constructed completely from natural materials, is a cultural relic from the medieval period particularly widespread in the southwestern region of Kosovo and northern region of Albania. The rectangular shape of a Kulla is produced with irregular stone ashlars, river pebbles and chestnut woods, however, the size and number of floors depends on the size of the family and their financial resources.

Literature

The roots of literature of the Albanian people can be traced to the Middle Ages with surviving works about history, theology and philosophy dating from the Renaissance.[301]

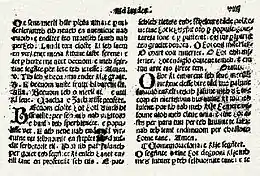

The earliest known use of written Albanian is a baptismal formula (1462) written by the Archbishop of Durrës Paulus Angelus.[302] In 1555, a Catholic clergyman Gjon Buzuku from the Shestan region published the earliest known book written in Albanian titled Meshari (The Missal) regarding Catholic prayers and rites containing archaic medieval language, lexemes and expressions obsolete in contemporary Albanian.[303] Other Christian clergy such as Luca Matranga in the Arbëresh diaspora published (1592) in the Tosk dialect while other notable authors were from northern Albanian lands and included Pjetër Budi, Frang Bardhi, and Pjetër Bogdani.[304]

In the 17th century and onwards, important contributions were made by the Arbëreshë people of Southern Italy who played an influential role in encouraging the Albanian Renaissance. Notable among them was figures such as Demetrio Camarda, Gabriele Dara, Girolamo de Rada, Giulio Variboba and Giuseppe Serembe who produced inspiring nationalist literature and worked to systematise the Albanian language.[305]

The Bejtexhinj in the 18th century emerged as the result of the influences of Islam and particularly Sufism orders moving towards Orientalism.[306] Individuals such as Nezim Frakulla, Hasan Zyko Kamberi, Shahin and Dalip Frashëri compiled literature infused with expressions, language and themes on the circumstances of the time, the insecurities of the future and their discontent at the conditions of the feudal system.[306]

The Albanian Renaissance in the 19th century is remarkable both for its valuable poetic achievement and for its variety within the Albanian literature. It drew on the ideas of Romanticism and Enlightenment characterised by its emphasis on emotion and individualism as well as the interaction between nature and mankind. Dora d'Istria, Girolamo de Rada, Naim Frashëri, Naum Veqilharxhi, Sami Frashëri and Pashko Vasa maintained this movement and are remembered today for composing series of prominent works.

The 20th century was centred on the principles of Modernism and Realism and characterised by the development to a more distinctive and expressive form of Albanian literature.[307] Pioneers of the time include Asdreni, Faik Konica, Fan Noli, Lasgush Poradeci, Migjeni who chose to portray themes of contemporary life and most notably Gjergj Fishta who created the epic masterpiece Lahuta e Malcís.[307]

After World War II, Albania emerged as a communist state and Socialist realism became part of the literary scene.[308] Authors and poets emerged such as Sejfulla Malëshova, Dritero Agolli and Ismail Kadare who has become an internationally acclaimed novelist and others who challenged the regime through various sociopolitical and historic themes in their works.[308] Martin Camaj wrote in the diaspora while in neighbouring Yugoslavia, the emergence of Albanian cultural expression resulted in sociopolitical and poetic literature by notable authors like Adem Demaçi, Rexhep Qosja, Jusuf Buxhovi.[309] The literary scene of the 21st century remains vibrant producing new novelists, authors, poets and other writers.[310]

Performing arts

Apparel

The Albanian people have incorporated various natural materials from their local agriculture and livestock as a source of attire, clothing and fabrics. Their traditional apparel was primarily influenced by nature, the lifestyle and has continuously changed since ancient times.[311] Different regions possesses their own exceptional clothing traditions and peculiarities varied occasionally in colour, material and shape.

The traditional costume of Albanian men includes a white skirt called Fustanella, a white shirt with wide sleeves, and a thin black jacket or vest such as the Xhamadan or Xhurdia. In winter, they add a warm woolen or fur coat known as Flokata or Dollama made from sheepskin or goat fur. Another authentic piece is called Tirq which is a tight pair of felt trousers mostly white, sometimes dark brown or black.

The Albanian women's costumes are much more elaborate, colorful and richer in ornamentation. In all the Albanian regions the women's clothing often has been decorated with filigree ironwork, colorful embroidery, a lot of symbols and vivid accessories. A unique and ancient dress is called Xhubleta, a bell shaped skirt reaching down to the calves and worn from the shoulders with two shoulder straps at the upper part.[312][313]

Different traditional handmade shoes and socks were worn by the Albanian people. Opinga, leather shoes made from rough animal skin, were worn with Çorape, knitted woolen or cotton socks. Headdresses remain a contrasting and recognisable feature of Albanian traditional clothing. Albanian men wore hats of various designs, shape and size. A common headgear is a Plis and Qylafë, in contrast, Albanian women wore a Kapica adorned with jewels or embroidery on the forehead, and a Lëvere or Kryqe which usually covers the head, shoulders and neck. Wealthy Albanian women wore headdresses embellished with gems, gold or silver.

Music

For the Albanian people, music is a vital component to their culture and characterised by its own peculiar features and diverse melodic pattern reflecting the history, language and way of life.[316] It rather varies from region to another with two essential stylistic differences between the music of the Ghegs and Tosks. Hence, their geographic position in Southeast Europe in combination with cultural, political and social issues is frequently expressed through music along with the accompanying instruments and dances.

Albanian folk music is contrasted by the heroic tone of the Ghegs and the relaxed sounds of the Tosks.[317] Traditional iso-polyphony perhaps represents the most noble and essential genre of the Tosks which was proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[318] Ghegs in contrast have a reputation for a distinctive variety of sung epic poetry often about the tumultuous history of the Albanian people.

There are a number of internationally acclaimed singers of ethnic Albanian origin such as Ava Max, Bebe Rexha, Dua Lipa, Era Istrefi, Rita Ora, and rappers such as Action Bronson, Dardan, Gashi and Loredana Zefi. Notable singers of Albanian origin from the former Yugoslavia include Selma Bajrami and Zana Nimani.

In international competitions, Albania participated in the Eurovision Song Contest for the first time in 2004. Albanians have also represented other countries in the contest: Anna Oxa for Italy in 1989, Adrian Gaxha for North Macedonia in 2008, Ermal Meta for Italy in 2018, Eleni Foureira for Cyprus in 2018, as well as Gjon Muharremaj for Switzerland in 2020 and 2021. Kosovo has never participated, but is currently applying to become a member of the EBU and therefore debut in the contest.

Religion

.jpg.webp)

Many different spiritual traditions, religious faiths and beliefs are practised by the Albanian people who historically have succeeded to coexist peacefully over the centuries in Southeast Europe. They are traditionally both Christians and Muslims—Catholics and Orthodox, Sunnis and Bektashis and—but also to a lesser extent Evangelicals, Protestants and Jews, constituting one of the most religiously diverse peoples of Europe.[319]

Christianity in Albania was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome until the 8th century. Then, dioceses in Albania were transferred to the patriarchate of Constantinople. In 1054 after the schism, the north became identified with the Roman Catholic Church.[320] Since that time all churches north of the Shkumbin river were Catholic and under the jurisdiction of the Pope.[321] Various reasons have been put forward for the spread of Catholicism among northern Albanians. Traditional affiliation with the Latin Church and Catholic missions in central Albania in the 12th century fortified the Catholic Church against Orthodoxy, while local leaders found an ally in Catholicism against Slavic Orthodox states.[322] [321][323] After the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans, Christianity began to be overtaken by Islam, and Catholicism and Orthodoxy continued to be practiced with less frequency.

During the modern era, the monarchy and communism in Albania as well as the socialism in Kosovo, historically part of Yugoslavia, followed a systematic secularisation of its people. This policy was chiefly applied within the borders of both territories and produced a secular majority of its population.

All forms of Christianity, Islam and other religious practices were prohibited except for old non-institutional pagan practices in the rural areas, which were seen as identifying with the national culture. The current Albanian state has revived some pagan festivals, such as the Spring festival (Albanian: Dita e Verës) held yearly on 14 March in the city of Elbasan. It is a national holiday.[324]

The communist regime which ruled Albania after World War II persecuted and suppressed religious observance and institutions, and entirely banned religion to the point where Albania was officially declared to be the world's first atheist state. Religious freedom returned to Albania following the regime's change in 1992. Albanian Sunni Muslims are found throughout the country, Albanian Orthodox Christians as well as Bektashis are concentrated in the south, while Roman Catholics are found primarily in the north of the country.[325]

According to the 2011 Census, which has been recognised as unreliable by the Council of Europe,[326] in Albania, 58.79% of the population adheres to Islam, making it the largest religion in the country. Christianity is practiced by 16.99% of the population, making it the second largest religion in the country. The remaining population is either irreligious or belongs to other religious groups.[327] Before World War II, there was given a distribution of 70% Muslims, 20% Eastern Orthodox, and 10% Roman Catholics.[328] Today, Gallup Global Reports 2010 shows that religion plays a role in the lives of only 39% of Albanians, and ranks Albania the thirteenth least religious country in the world.[329]

For part of its history, Albania has also had a Jewish community. Members of the Jewish community were saved by a group of Albanians during the Nazi occupation.[330] Many left for Israel c. 1990–1992 when the borders were opened after the fall of the communist regime, but about 200 Jews still live in Albania.

| Religion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam | 21%[333] to 82%[334] | 88.8 to 95.60[335] | 98.62[335] | 73.15 | 71.06 | 54.78 | 41.49 |

| Sunni | 56.70 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Bektashi | 2.09 to 7.5[336] | — | — | — | - | — | - |

| Christians | 9[333] to 28.64[336] | 3.69 to 6.20[335] | 1.37 | 26.37 | 19.54 | 40.69 | 38.85 |

| Catholic | 3%[333] to 13.82[336] | 2.20 to 5.80[335] | 1.37 | 26.13 | 16.84 | 40.59 | 27.67 |

| Orthodox | 6[333] to 13.08[336] | 1.48 | — | 0.12 | 2.60 | 0.01 | 11.02 |

| Protestants | 0.14 to 1.74[336] | 0.16 | — | - | 0.03 | — | — |

| Other Christians | 0.07 | — | — | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.09 | — |

| Unaffiliated or Irreligious | 24.21% to 62.7%[337] | ||||||

| Atheist | 2.50% to 9%[338] | 0.07 to 2.9[335] | — | 0.11 | 2.95 | 1.80 | 17.81 |

| Prefer to not answer | 1%[336] to 13.79% | 0.55 | 0.19 | 2.36 | 1.58 | — | — |

| Agnostic | 5.58[337] | 0.02 | |||||

| Believers without denomination | 5.49 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Not relevant/not stated | 2.43 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 4.82 | — | |

| Other religion | 1.19[336] | 0.03 | 1.85 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sunni Islam is the largest denomination of the Albanian people in Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and North Macedonia.

- ↑ Roman Catholicism (both Latin and Greek-Byzantine rites) is the largest Christian denomination of the Albanian people in northern Albania, Croatia and Italy.

- ↑ Eastern Orthodoxy is the largest Christian denomination of the Albanian people in southern Albania, North Macedonia and Greece.

- ↑ See:[69][70][71][72]

- ↑ See:[84][81][82][83][85][86]

- ↑ Widely fluctuating numbers for groups in Albania are due to various overlapping definitions based on how groups can be defined, as religion can be defined in Albania either by family background, belief or practice

References

Citations

- ↑ Carl Skutsch, Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities, Routledge, 2013 ISBN 1135193886, p. 65.

- ↑ Steven L. Danver, Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues:, Routledge, 2015, ISBN 1317463994, p. 260.

- ↑ Mary Rose Bonk. Worldmark Yearbook, Band 1. Gale Group, 2000. p. 37.

- ↑ National Geographic, Band 197 (University of Michigan ed.). National Geographic Society, 2000. 2000. p. 59. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ↑ Over 20 Peace Corps Language Training Publications–Country Pre-departure Materials. Jeffrey Frank Jones. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ↑ "Albania". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 27 September 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- ↑ "Kosovo". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 27 September 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- 1 2 "Kosovari in Italia – statistiche e distribuzione per regione". Tuttitalia.it.

- 1 2 "Arbëreshiski language of Italy – Ethnic population: 260,000 (Stephens 1976)". Ethnologue.

- ↑ "Cittadini non-comunitari regolarmente presenti". istat.it. 4 August 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014.

- ↑ Gemi, Eda (February 2017). "Albanian Migration in Greece: Understanding Irregularity in a Time of Crisis". European Journal of Migration and Law. 19 (1): 18. doi:10.1163/15718166-12342113.

- 1 2 Cela; et al. (January 2018). ALBANIA AND GREECE: UNDERSTANDING AND EXPLAINING (PDF). Tirana: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. pp. 20–36.

- 1 2 Adamczyk, Artur (15 June 2016). "Albanian Immigrants in Greece From Unwanted to Tolerated?" (PDF). Journal of Liberty and International Affairs. 2 (1): 53.

- ↑ Vathi, Zana. Migrating and settling in a mobile world: Albanian migrants and their children in Europe. Springer Nature, 2015.

- ↑ Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. By Philip L. Martin, Susan Forbes Martin, Patrick Weil

- ↑ "Announcement of the demographic and social characteristics of the Resident Population of Greece according to the 2011 Population – Housing Census" [Graph 7 Resident population with foreign citizenship] (PDF). Greek National Statistics Agency. 23 August 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2013.

- ↑ Julie Vullnetari (2012). Albania on the Move: Links Between Internal and International Migration (PDF). Amsterdam University Press, 2012. p. 73. ISBN 9789089643551.

To this, weneed to add an estimate of irregular migrants; some Greek researchers haveargued that Albanians have a rate of 30 per cent irregularity in Greece, butthis is contested as rather high by others (see Maroukis 2009: 62). If we accept a more conservative share than that–e.g. 20 per cent–we come toa total of around 670,000 for all Albanian migrants in Greece in 2010, which is rather lower than that supplied by NID (Table 3.2). In a countrywith a total population of around eleven million, this is nevertheless a con-siderable presence: around 6 per cent of the total population

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2021". stat.gov.mk (in English and Macedonian). State Statistical Office of the Republic of North Macedonia.

- 1 2 3 "Official Results of Monenegrin Census 2011" (PDF). Statistical Office of Montenegro. n.d. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "Final results - Ethnicity". Почетна. 14 July 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ↑ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ↑ "7. Prebivalstvo po narodni pripadnosti, Slovenija, popisi 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991 in 2002". stat.si (in Slovenian).

- ↑ "Población y edad media por nacionalidad y sexo" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ↑ "POPULAÇÃO ESTRANGEIRA RESIDENTE EM TERRITÓRIO NACIONAL – 2022" (PDF).

- ↑ "Albanians in the UK" (PDF). unitedkingdom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2020.