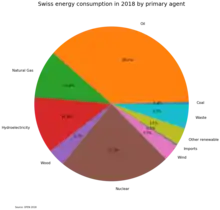

The energy sector in Switzerland is, by its structure and importance, typical of a developed country.[1] Apart from hydroelectric power and firewood, the country has few indigenous energy resources: oil products, natural gas and nuclear fuel are imported, so that in 2013 only 22.6% of primary energy consumption was supplied by local resources.

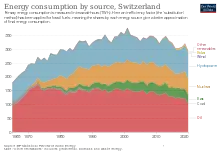

Final energy consumption in Switzerland has increased more than fivefold since the beginning of the 20th century, from around 170,000 to 896,000 terajoules per year, with the largest share now being captured by transport (35% in 2013). This increase was made in parallel with the strong development of its economy and the increase in population. As the sector is highly liberalised, the federal energy policy aims to accompany the promises made in Kyoto by promoting a more rational use of energy and, particularly since the 1990s, the development of new renewable sources.

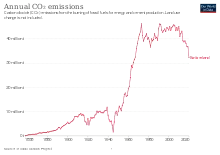

Thanks to the high share of hydroelectricity (59.6%) and nuclear power (31.7%) in electricity production, Switzerland's per capita energy-related CO2 emissions are 28% lower than the European Union average and roughly equal to those of France.

Following the earthquake that struck Japan in March 2011 and the Fukushima nuclear accident, the Federal Council announced on 25 May 2011 a phase-out of nuclear energy scheduled for 2034.

In September 2016, both chambers of the Swiss Parliament voted for the Energiestrategie 2050, a set of measures to replace electrical energy produced by atomic reactors with renewable energy, reduce the use of fossil fuel and increase the efficiency of energy consumption. This decision was challenged by a national Referendum. In May 2017, the Swiss people voted against the Referendum, thereby confirming the decision taken by the parliament.[2]

History

The energy economy in Switzerland developed similarly to the rest of Europe, but with some delay until 1850. There are three different periods. An agrarian society until the mid-nineteenth century, Switzerland's small scale energy economy was based on wood and biomass (plants feeding the animal and human labour), which was in general renewable energy. Also used were wind power and hydraulic power, and, from the eighteenth century, indigenous coal.

The industrial society, from 1860 to 1950, had to import coal as it was the main source of energy but not readily available as a natural resource. Another important source of energy was water power at low or high pressure. The current consumer society, developed using mostly oil, natural gas, water power (turbines) to a lesser extent, and later nuclear energy. The oil crisis and pollution of the environment prompted the increased use of renewable energy. It is notable that 100% of the Swiss railway network is electrified. The high proportion of energy generated through hydroelectric power and the lack of natural resources (such as coal and oil) help to explain why such a situation is strategically beneficial in Switzerland.

Energy statistics

|

|

|

CO2 emissions: |

Energy plan

On 21 May 2017, Swiss voters accepted the new Energy Act establishing the 'energy strategy 2050'. The aims of the energy strategy 2050 are:[4]

- to reduce energy consumption,

- to increase energy efficiency and

- to promote renewable energies (such as water, solar, wind and geothermal power as well as biomass fuels).

The object being to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050

The Energy Act of 2006 forbids the construction of new nuclear power plants in Switzerland.[4]

Reports suggest that electricity demand could increase by up to 30% by 2050 (46% if you include a demand for green hydrogen).[5]

Energy types

Renewable energy in Switzerland

| Achievement | Year | Achievement | Year | Achievement | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15% | <1990 | 20% | 2008 | 25% | 2013[3] |

Renewable energy includes wind, solar, biomass and geothermal energy sources.

The Swiss government has set a target to cut fossil fuel use 20% by the year 2020.[6] Most of the energy produced within Switzerland is renewable from hydropower and biomass. However this only accounts for around 15% of total overall energy consumption as the other 85% of energy used is imported, mostly derived from fossil fuels.

Wind

In 2023 there were 41 operating wind turbines with 87 MW capacity, producing 0.15 terawatt-hours.[7]

There has been a proposal to produce around 600 GWh (< 0.2%) of electricity per annum using wind turbines by 2030.[8] Switzerland's wind power potential is several TWh per year.[9]

The Swiss Energy Strategy for 2050 aims to increase production from wind energy to 4.3 TWh a year, this would generate around 7% of the country's electricity.[7]

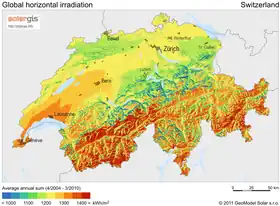

Solar

Solar energy in Switzerland in 2016 only accounted for 0.04% of total energy production.[10] The cost of solar energy is significantly higher than competing sources in Switzerland such as hydro. As costs of solar come down it is likely to become more market competitive. It is currently subsidised in an attempt to make it more competitive and attractive.

In 2019, Switzerland announced plans of large scale solar auctions,[11] and in 2021 and 2022 installations increased, with 4.7GW of total installed capacity in 2022.

Biomass

Biomass provides around 5% of electricity capacity.

Hydro power

Based on the estimated mean production level, hydropower still accounted for almost 90% of domestic electricity production at the beginning of the 1970s, but this figure fell to around 60% by 1985 following the commissioning of Switzerland's nuclear power plants, and is now around 56%. Hydropower therefore remains Switzerland's most important domestic source of renewable energy.[12] Hydro energy was meaning to be taken down in 2013 with new laws on energy to be put in place but they were scrapped for a more eco friendly plan.

Hydroelectric companies received support from the state (for instance in the 2010s). Critics pointed out the lack of independence of the political institutions (cantonal and federal), of which several elected members are connected with the hydroelectric industry.[13]

Nuclear power

Switzerland has four operational reactors and two that have ceased operations. The operational four are two large (>1,000 MW) and two small (365 MW). In 2020 the reactors produced 24.0 TWh which was 34% of electricity generated.[14]

Switzerland has set a target date of 2044 to phase out nuclear power.[5]

Electricity

Switzerland's per capita electricity consumption is slightly higher than that of its neighbours.[15]

Production of electricity (2008):[16]

- Hydropower plants, 56%

- Nuclear power plants, 39%

- Thermal power and other power plants, 5%

The Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE) is within the Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC). SwissEnergy is a program aiming at promoting energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy with the collaboration of the cantons and municipalities, and partners from trade and industry, environmental and consumer organisations.

A report was published in 2011 by the World Energy Council in association with Oliver Wyman, entitled Policies for the future: 2011 Assessment of country energy and climate policies, which ranks country performance according to an energy sustainability index.[17] The best performers were Switzerland, Sweden and France.

A report in 2021 states that the majority of the Swiss electricity grid is old and in need of investment. The high voltage system needs to be upgraded from 220 to 380 kilovolt (kV) stations to better connect to neighbouring countries.[5]

Carbon dioxide emissions

A study published in 2009 showed that the emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) due to the electricity consumed in Switzerland (total: 5.7 million tonnes) were seven times higher than the emissions of carbon dioxide due to the electricity produced in Switzerland (total: 0.8 million tonnes).[18]

The study also showed that the production in Switzerland (64.6 TWh) was similar to the amount of electricity consumed in the country (63.7 TWh).[18] Overall, Switzerland exported 7.6 TWh and imported 6.8 TWh; but, in terms of emissions of carbon dioxide, Switzerland exported "clean" electricity causing emissions of 0.1 million tonnes of CO2 and imported "dirty" electricity causing emissions of 5 million tonnes of CO2.[18]

The electricity produced in Switzerland generated about 14 grammes of CO2 per kilowatt hour. The electricity consumed in Switzerland generated about 100 grammes of CO2 per kilowatt hour.[19]

Carbon tax

In January 2008, Switzerland implemented a carbon tax on all hydrocarbon fuels, unless are used for energy. Gasoline and diesel fuels are not affected. It is an incentive tax because it is designed to promote the economic use of hydrocarbon fuels.[20] The tax amounts to SFr 12 per tonne CO2, the equivalent of SFr 0.03 per litre of heating oil (US$0.108 per gallon) and SFr 0.025 per m3 of natural gas (US$0.024 per m3).[21] Switzerland prefers to rely on voluntary actions and measures to reduce emissions. The law mandated a CO2 tax if voluntary measures proved to be insufficient.[22] In 2005, the federal government decided that additional measures were needed to meet Kyoto Protocol commitments of an 8% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012.[23] In 2007, the CO2 tax was approved by the Swiss Federal Council, coming into effect in 2008.[21] In 2010, the highest tax rate was to be CHF 36 per tonne of CO2 (US$34.20 per tonne CO2).[24]

Companies are allowed to escape the tax by participating in emissions trading where they voluntarily commit to legally binding reduction targets.[25] Emission allowances are given to companies for free, and each year emission allowances equal to the amount of additional CO2 emitted must be surrendered by the company. Companies are allowed to sell or trade excess permits. However, a company that fails to surrender sufficient allowances must pay the tax retroactively for each tonne emitted since the exemption was granted.[23] As of 2009 some 400 companies operated under this program. In 2008 and 2009 the companies returned enough credits to the Swiss government to cover their CO2 emissions. The companies emitted about 2.6 million tonnes, well below the limit of 3.1 million tonnes.[26] Switzerland issued so many allowances that few emissions permits were traded.[27]

The tax is revenue-neutral because revenues are redistributed to companies and to the Swiss population. For example, if the population bears 60% of the tax burden, it receives 60% of the rebate. Revenues are redistributed to all payers, except those who exempt themselves from the tax through the cap-and-trade program.[24] The revenue is given to companies in proportion to payroll.[28] Tax revenues that were paid by the population are redistributed equally to all residents.[24][28] In June 2009, the Swiss Parliament allocated about one-third of the carbon tax revenue to a 10-year construction initiative. This program promotes building renovations, renewable energies, waste heat reruse, and building engineering.[24]

Tax revenue from 2008 to 2010 were distributed in 2010.[24] In 2008, the tax raised around CHF 220 million (US$209 million) in revenue. As of 16 June 2010, a total of around SFr 360 million (US$342 million) had become available for distribution.[28] The 2010 revenue was about SFr 630 million (US$598 million). SFr 200 million (US$190 million) was to be allocated for the building program, while the remaining SFr 430 million (US$409 million) was to be redistributed to the population.[24] IEA commended Switzerland's tax for its design and that tax revenues would be recycled as "sound fiscal practice".[23]

Since 2005, transport fuels in Switzerland have been subjected to the Climate Cent Initiative surcharge—a surcharge of SFr 0.015 per liter on gasoline and diesel (US$0.038 per gallon). However, this surcharge was supplemented with a CO2 tax on transport fuels if emissions reductions are not satisfactory. In their 2007 review, IEA recommended that Switzerland implement a CO2 tax on transport fuels or increase the Climate Cent surcharge to better balance the costs of meeting emissions reductions targets across sectors.[29]

See also

Notes and references

- Energy in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Notter, Dominic A. (1 January 2015). "Small country, big challenge: Switzerland's upcoming transition to sustainable energy". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 71 (4): 51–63. Bibcode:2015BuAtS..71d..51N. doi:10.1177/0096340215590792. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 145693743.

- ↑ Energy Strategy 2050. Swiss Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- 1 2 "Energy consumption in Switzerland". 2020.

- 1 2 Energy strategy 2050, Swiss Federal Office of Energy, Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (page visited on 21 May 2017).

- 1 2 3 "The role of the electric grid in Switzerland's energy future". 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Focus, Expat. "Switzerland - Renewable Energy - ExpatFocus.com". expatfocus.com. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- 1 2 "Will the Swiss countryside soon be dotted with wind turbines?". 18 April 2023.

- ↑ "Wind energy". admin.ch. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ "Switzerland has potential for almost 30 TWh of wind energy". Renewablesnow.com. 2 September 2022.

- ↑ "Solar energy". admin.ch. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ "Switzerland plans large scale solar auctions". list.solar. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ↑ "Hydropower". admin.ch. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ (in French) Kurt Marti, "Les nombreuses casquettes des lobbyistes de l'hydroélectricité", Pro natura magazine, Pro Natura, July 2016, pages 18-20.

- ↑ "Nuclear Power in Switzerland". June 2023.

- ↑ Energy policy swissworld.org, Retrieved on 2009-06-23

- ↑ Record electricity consumption in Switzerland Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine admin.ch

- ↑ "World Energy Council". Archived from the original on 2011-11-20. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- 1 2 3 (in French) TEP Energy GmbH, "Intensité CO2 de l’électricité vendue aux consommateurs finaux en Suisse", 17 July 2009 (page visited on 6 October 2013).

- ↑ (in French) Isabelle Chevalley, "D’où vient l’électricité que vous consommez ?", Le Temps, 7 October 2009 (page visited on 6 October 2013).

- ↑ Federal Office for the Environment (2010). "CO2 tax". Agency for the Environment FOEN. p. 1. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- 1 2 IEA (2008). "CO2 Tax on Stationary Fuels". International Energy Agency's website. p. 1. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ↑ IEA (2000). "Implementation of the Law on the Reduction of CO2 Emissions (CO2 Law)". International Energy Agency's website. p. 1. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 IEA (2007). "Energy Policies of IEA Countries – Switzerland" (PDF). International Energy Agency's website. p. 128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Agency for the Environment FOEN (2010). "Redistribution of CO2 tax". Agency for the Environment FOE. p. 1. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ Parliament, European (2008). "Options and Implications of Linking the EU ETS with other Emissions Trading Schemes". European Parliament. p. 30. Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ↑ Agency for the Environment FOEN (2010). "Companies exceed CO2 targets in 2009". Federal Office for Environment. p. 1. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ Broom, Giles (2009). "Swiss Favour Carbon Tax Over Emissions Trading". Swisster. p. 1. Archived from the original on 9 December 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Agency for the Environment FOEN (2010). "Redistribution of the CO2 tax: The economy receives some 360 million francs". Federal Office for Environment. p. 1. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ IEA (2007). "Energy Policies of IEA Countries – Switzerland" (PDF). International Energy Agency. p. 128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

External links

- Swiss Federal Office of Energy

- Energy in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

.svg.png.webp)