Dynamic covalent chemistry (DCvC) is a synthetic strategy employed by chemists to make complex molecular and supramolecular assemblies from discrete molecular building blocks.[1] DCvC has allowed access to complex assemblies such as covalent organic frameworks, molecular knots, polymers, and novel macrocycles.[2] Not to be confused with dynamic combinatorial chemistry, DCvC concerns only covalent bonding interactions. As such, it only encompasses a subset of supramolecular chemistries.

The underlying idea is that rapid equilibration allows the coexistence of a variety of different species among which molecules can be selected with desired chemical, pharmaceutical and biological properties. For instance, the addition of a proper template will shift the equilibrium toward the component that forms the complex of higher stability (thermodynamic template effect). After the new equilibrium is established, the reaction conditions are modified to stop equilibration. The optimal binder for the template is then extracted from the reactional mixture by the usual laboratory procedures. The property of self-assembly and error-correcting that allow DCvC to be useful in supramolecular chemistry rely on the dynamic property.

Dynamic systems

Dynamic systems are collections of discrete molecular components that can reversibly assemble and disassemble. Systems may include multiple interacting species leading to competing reactions.

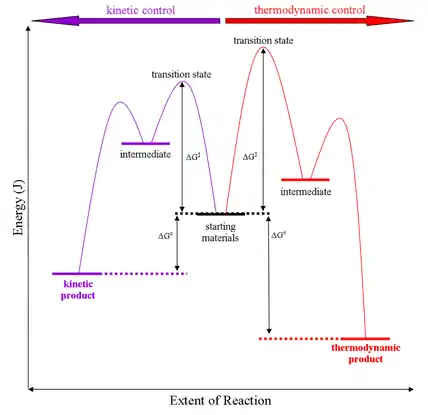

Thermodynamic control

In dynamic reaction mixtures, multiple products exist in equilibrium. Reversible assembly of molecular components generates products and semi-stable intermediates. Reactions can proceed along kinetic or thermodynamic pathways. Initial concentrations of kinetic intermediates are greater than thermodynamic products because the lower barrier of activation (ΔG‡), compared to the thermodynamic pathway, gives a faster rate of formation. A kinetic pathway is represented in figure 1 as a purple energy diagram. With time, the intermediates equilibrate towards the global minimum, corresponding to the lowest overall Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), shown in red on the reaction diagram in figure 1. The driving force for products to re-equilibrate towards the most stable products is referred to as thermodynamic control. The ratio of products to at any equilibrium state is determined by the relative magnitudes of free energy of the products. This relationship between population and relative energies is called the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

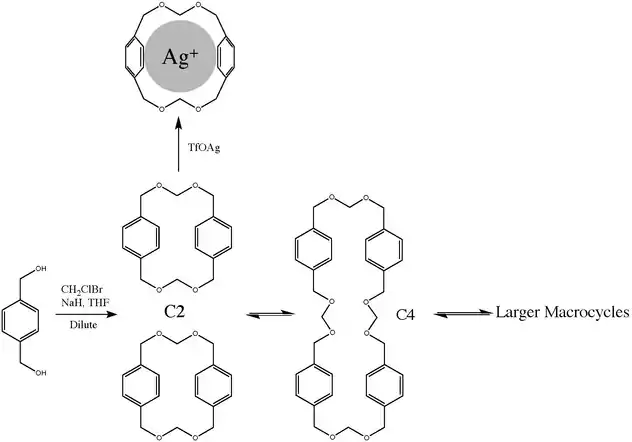

Thermodynamic template effect

The concept of a thermodynamic template is demonstrated in scheme 1. A thermodynamic template is a reagent that can stabilize the form of one product over others by lowering its Gibb's free energy (ΔG°) in relation to other products. cyclophane C2 can be prepared by the irreversible highly diluted reaction of a diol with chlorobromomethane in the presence of sodium hydride. The dimer however is part of series of equilibria between polyacetal macrocycles of different size brought about by acid catalyzed (triflic acid) transacetalization.[4] Regardless of the starting material, C2, C4 or a high molar mass product, the equilibrium will eventually produce a product distribution across many macrocycles and oligomers. In this system it is possible to amplify the presence of C2 in the mixture when the transacetalisation catalyst is silver triflate because the silver ion fits ideally and irreversibly in the C2 cavity.

Synthetic methods

Reactions used in DCvC must generate thermodynamically stable products to overcome the entropic cost of self-assembly. The reactions must form covalent linkages between building blocks. Finally, all possible intermediates must be reversible, and the reaction ideally proceeds under conditions that are tolerant of functional groups elsewhere in the molecule.

Reactions that can be used in DCvC are diverse and can be placed into two general categories. Exchange reactions involve the substitution of one reaction partner in an intermolecular reaction for another with an identical type of bonding. Some examples of this are shown in schemes 5 and 8, in an ester exchange, and disulfide exchange reactions. The second type, formation reactions, rely on the formation of new covalent bonds. Some examples include Diels–Alder and aldol reactions. In some cases, a reaction can pertain to both categories. For example, Schiff base formation can be categorized as a forming new covalent bonds between a carbonyl and primary amine. However, in the presence of two different amines the reaction becomes an exchange reaction where the two imine derivatives compete in equilibrium.

Exchange and formation reactions can be further broken down into three categories:

- Bonding between carbon–carbon

- Bonding between carbon–heteroatom

- Bonding between heteroatom–heteroatom

Carbon–carbon

Bond formation between carbon atoms forms very thermodynamically stable products. Therefore, they often require the use of a catalyst to improve kinetics and ensure reversibility.

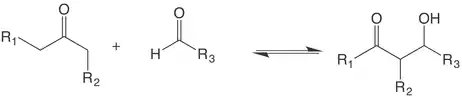

Aldol reactions

Aldol reactions are commonly used in organic chemistry to form carbon-to-carbon bonds. The aldehyde-alcohol motif common to the reaction product is ubiquitous to synthetic chemistry and natural products. The reaction utilizes two carbonyl compounds to generate a β-hydroxy carbonyl. Catalysis is always necessary because the barrier of activation between kinetic products and starting materials makes the dynamic reversible process too slow. Catalysts that have been successfully employed include enzymatic aldolase and Al2O3 based systems.[5]

Diels–Alder

.tif.png.webp)

[4+2] cycloadditions of a diene and an alkene have been used as DCvC reactions. These reactions are often reversible at high temperatures. In the case of furan–maleimide adducts, the retro-cycloaddition is accessible at temperatures as low as 40 °C.[6]

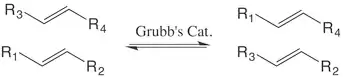

Metathesis

Olefin and alkyne metathesis refers to a carbon–carbon bond forming reaction. In the case of olefin metathesis, the bond forms between two sp2-hybridized carbon centers. In alkyne metathesis it forms between two sp-hybridized carbon centers.[7] Ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) can be used in polymerization and macrocycle synthesis.[1]

Carbon–heteroatom

A common dynamic covalent building motif is bond formation between a carbon center and a heteroatom such as nitrogen or oxygen. Because the bond formed between carbon and a heteroatom is less stable than a carbon-carbon bond, they offer more reversibility and reach thermodynamic equilibrium faster than carbon bond forming dynamic covalent reactions.

Ester exchange

Ester exchange takes place between an ester carbonyl and an alcohol. Reverse esterification can take place via hydrolysis. This method has been used extensively in polymer synthesis.[8]

Imine and aminal formation

Bond forming reactions between carbon and nitrogen are the most widely used in dynamic covalent chemistry. They have been used more broadly in materials chemistry for molecular switches, covalent organic frameworks, and in self-sorting systems.[1]

Imine formation takes place between an aldehyde or ketone and a primary amine. Similarly, aminal formation takes place between an aldehyde or ketone and a vicinal secondary amine.[8] Both reactions are commonly used in DCvC.[1] While both reactions can initially be categorized as formation reactions, in the presence of one or more of either reagent, the dynamic equilibrium between carbonyl and amine becomes an exchange reaction.

.tif.png.webp)

Heteroatom–heteroatom

Dynamic heteroatom bond formation, presents useful reactions in the dynamic covalent reaction toolbox. Boronic acid condensation (BAC) and disulfide exchange constitute the two main reactions in this category.[1]

Disulfide exchange

Disulfides can undergo dynamic exchange reactions with free thiols. The reaction is well documented within the realm of DCvC, and is one of the first reactions demonstrated to have dynamic properties.[1][9] The application of disulfide chemistry has the added advantage of being a biological motif. Cysteine residues can form disulfide bonds in natural systems.[1]

Boronic acid

Boronic acid self-condensation or condensation with diols is a well-documented dynamic covalent reaction. The boronic acid condensation has the characteristic of forming two dynamic bonds with various substrates. This is advantageous when designing systems where high rigidity is desired, such as 3-D cages and COFs.[10]

Applications

Dynamic covalent chemistry has allowed access to a wide variety of supramolecular structures. Using the above reactions to link molecular fragments, higher order materials have been made. These materials include macrocycles, COFs, and molecular knots. The applications of these products have been used in gas storage, catalysis, and biomedical sensing, among others.[1]

Dynamic signaling cascades

Dynamic covalent reactions have recently been used in Systems chemistry to initiate signaling cascades by reversibly releasing protons. The dynamic nature of the reactions provides a suitable "on-off" switch-like nature to the cascade systems.[11]

Macrocycles

Many examples exist that demonstrate the utility of DCvC in macrocycle synthesis. This type of chemistry is effective for large macrocycle synthesis because the thermodynamic template effect is well suited to stabilize ring structures. Furthermore, the error-correcting ability inherent to DCvC allows large structures to be made without flaws.[12][13]

Covalent organic frameworks

All current methods of covalent organic framework (COF) synthesis use DCvC. Boronic acid dehydration, as demonstrated by Yaghi et al. is the most common type of reaction used.[14] COFs have been used in gas storage, catalysis, . Possible morphologies include infinite covalent 3D frameworks, 2D polymers, or discrete molecular cages.

Molecular knots

DCvC has been used to make molecules with complex topological properties. In the case of Borromean rings, DCvC is used to synthesize a three ring interlocking system. Thermodynamic templates are used to stabilize interlocking macrocycle growth.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jin, Yinghua; Yu, Chao; Denman, Ryan J.; Zhang, Wei (2013-08-21). "Recent advances in dynamic covalent chemistry". Chemical Society Reviews. 42 (16): 6634–6654. doi:10.1039/c3cs60044k. ISSN 1460-4744. PMID 23749182.

- ↑ Jin, Yinghua; Wang, Qi; Taynton, Philip; Zhang, Wei (2014-05-20). "Dynamic Covalent Chemistry Approaches Toward Macrocycles, Molecular Cages, and Polymers". Accounts of Chemical Research. 47 (5): 1575–1586. doi:10.1021/ar500037v. ISSN 0001-4842. PMID 24739018.

- ↑ "Thermodynamic versus kinetic control" by Nick024 - Own work. Licensed under CC0 via Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thermodyamic_versus_kinetic_control.png#/media/File:Thermodyamic_versus_kinetic_control.png

- ↑ This particular type of transacetalization goes by the name of formal metathesis because it is reminiscent of olefin metathesis but then with formaldehyde.

- ↑ Zhang, Yan; Vongvilai, Pornrapee; Sakulsombat, Morakot; Fischer, Andreas; Ramström, Olof (2014-03-24). "Asymmetric Synthesis of Substituted Thiolanes through Domino Thia-Michael–Henry Dynamic Covalent Systemic Resolution using Lipase Catalysis". Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis. 356 (5): 987–992. doi:10.1002/adsc.201301033. ISSN 1615-4150. PMC 4498465. PMID 26190961.

- ↑ Boutelle, Robert C.; Northrop, Brian H. (2011-10-07). "Substituent effects on the reversibility of furan-maleimide cycloadditions". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 76 (19): 7994–8002. doi:10.1021/jo201606z. ISSN 1520-6904. PMID 21866976.

- ↑ Vougioukalakis, Georgios C.; Grubbs, Robert H. (2010-03-10). "Ruthenium-Based Heterocyclic Carbene-Coordinated Olefin Metathesis Catalysts". Chemical Reviews. 110 (3): 1746–1787. doi:10.1021/cr9002424. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 20000700.

- 1 2 Bozdemir, O. Altan; Barin, Gokhan; Belowich, Matthew E.; Basuray, Ashish N.; Beuerle, Florian; Stoddart, J. Fraser (2012-09-26). "Dynamic covalent templated-synthesis of [c2]daisy chains". Chemical Communications. 48 (84): 10401–10403. doi:10.1039/C2CC35522A. PMID 22982882. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Kim, Jeehong; Baek, Kangkyun; Shetty, Dinesh; Selvapalam, Narayanan; Yun, Gyeongwon; Kim, Nam Hoon; Ko, Young Ho; Park, Kyeng Min; Hwang, Ilha (2015-02-23). "Reversible Morphological Transformation between Polymer Nanocapsules and Thin Films through Dynamic Covalent Self-Assembly". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 54 (9): 2693–2697. doi:10.1002/anie.201411842. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 25612160.

- ↑ Nishiyabu, Ryuhei; Kubo, Yuji; James, Tony D.; Fossey, John S. (2011-01-28). "Boronic acid building blocks: tools for self assembly". Chemical Communications. 47 (4): 1124–1150. doi:10.1039/c0cc02921a. ISSN 1364-548X. PMID 21113558.

- ↑ Ren, Yulong; You, Lei (2015-11-11). "Dynamic Signaling Cascades: Reversible Covalent Reaction-Coupled Molecular Switches". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 137 (44): 14220–14228. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b09912. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 26488558.

- ↑ Cacciapaglia, Roberta; Di Stefano, Stefano; Mandolini, Luigi (2005-10-05). "Metathesis reaction of formaldehyde acetals: an easy entry into the dynamic covalent chemistry of cyclophane formation". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (39): 13666–13671. doi:10.1021/ja054362o. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 16190732.

- ↑ Kornienko, Nikolay; Zhao, Yingbo; Kley, Christopher S.; Zhu, Chenhui; Kim, Dohyung; Lin, Song; Chang, Christopher J.; Yaghi, Omar M.; Yang, Peidong (2015-10-28). "Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 137 (44): 14129–14135. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b08212. PMID 26509213. S2CID 14793796.

- ↑ Bunck, David N.; Dichtel, William R. (2012-02-20). "Internal Functionalization of Three-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 51 (8): 1885–1889. doi:10.1002/anie.201108462. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 22249947.