A diol is a chemical compound containing two hydroxyl groups (−OH groups).[1] An aliphatic diol is also called a glycol.[2] This pairing of functional groups is pervasive, and many subcategories have been identified.

The most common industrial diol is ethylene glycol. Examples of diols in which the hydroxyl functional groups are more widely separated include 1,4-butanediol HO−(CH2)4−OH and propylene-1,3-diol, or beta propylene glycol, HO−CH2−CH2−CH2−OH.

Synthesis of classes of diols

Geminal diols

A geminal diol has two hydroxyl groups bonded to the same atom. These species arise by hydration of the carbonyl compounds. The hydration is usually unfavorable, but a notable exception is formaldehyde which, in water, exists in equilibrium with methanediol H2C(OH)2. Another example is (F3C)2C(OH)2, the hydrated form of hexafluoroacetone. Many gem-diols undergo further condensation to give dimeric and oligomeric derivatives. This reaction applies to glyoxal and related aldehydes.

Vicinal diols

In a vicinal diol, the two hydroxyl groups occupy vicinal positions, that is, they are attached to adjacent atoms. These compounds are called glycols. Examples include ethane-1,2-diol or ethylene glycol HO−(CH2)2−OH, a common ingredient of antifreeze products. Another example is propane-1,2-diol, or alpha propylene glycol, HO−CH2−CH(OH)−CH3, used in the food and medicine industry, as well as a relatively non-poisonous antifreeze product.

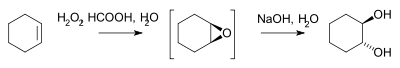

On commercial scales, the main route to vicinal diols is the hydrolysis of epoxides. The epoxides are prepared by epoxidation of the alkene. An example in the synthesis of trans-cyclohexanediol[3] or by microreactor:[4]

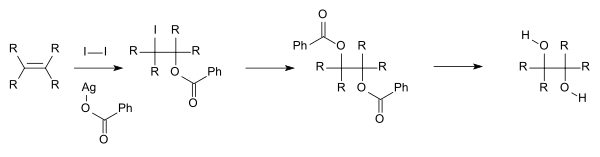

For academic research and pharmaceutical areas, vicinal diols are often produced from the oxidation of alkenes, usually with dilute acidic potassium permanganate. Using alkaline potassium manganate(VII) produces a colour change from clear deep purple to clear green; acidic potassium manganate(VII) turns clear colourless. Osmium tetroxide can similarly be used to oxidize alkenes to vicinal diols. The chemical reaction called Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation can be used to produce chiral diols from alkenes using an osmate reagent and a chiral catalyst. Another method is the Woodward cis-hydroxylation (cis diol) and the related Prévost reaction (anti diol), depicted below, which both use iodine and the silver salt of a carboxylic acid.

Other routes to vic-diols are the hydrogenation of acyloins[5] and the pinacol coupling reaction.

1,3-Diols

1,3-Diols are often prepared industrially by aldol condensation of ketones with formaldehyde. The resulting carbonyl is reduced using the Cannizzaro reaction or by catalytic hydrogenation:

- RC(O)CH3 + CH2O → RC(O)CH2CH2OH

- RC(O)CH2CH2OH + H2 → RCH(OH)CH2CH2OH

2,2-Disubstituted propane-1,3-diols are prepared in this way. Examples include 2-methyl-2-propyl-1,3-propanediol and neopentyl glycol.

1,3-Diols can be prepared by hydration of α,β-unsaturated ketones and aldehydes. The resulting keto-alcohol is hydrogenated. Another route involves the hydroformylation of epoxides followed by hydrogenation of the aldehyde. This method has been used for 1,3-propanediol from ethylene oxide.

More specialized routes to 1,3-diols involves the reaction between an alkene and formaldehyde, the Prins reaction. 1,3-diols can be produced diastereoselectively from the corresponding β-hydroxy ketones using the Evans–Saksena, Narasaka–Prasad or Evans–Tishchenko reduction protocols.

1,3-Diols are described as syn or anti depending on the relative stereochemistries of the carbon atoms bearing the hydroxyl functional groups. Zincophorin is a natural product that contains both syn and anti 1,3-diols.

1,4-, 1,5-, and longer diols

Diols where the hydroxyl groups are separated by several carbon centers are generally prepared by hydrogenation of diesters of the corresponding dicarboxylic acids:

- (CH2)n(CO2R)2 + 4 H2 → (CH2)n(CH2OH)2 + 2 H2O + 2 ROH

1,4-butanediol, 1,5-pentanediol, 1,6-hexanediol, 1,10-decanediol are important precursors to polyurethanes.[6]

Reactions

From the industrial perspective, the dominant reactions of the diols is in the production of polyurethanes and alkyd resins.[6]

General diols

Diols react as alcohols, by esterification and ether formation.

Diols such as ethylene glycol are used as co-monomers in polymerization reactions forming polymers including some polyesters and polyurethanes. A different monomer with two identical functional groups, such as a dioyl dichloride or dioic acid is required to continue the process of polymerization through repeated esterification processes.

A diol can be converted to cyclic ether by using an acid catalyst, this is diol cyclization. Firstly, it involves protonation of the hydroxyl group. Then, followed by intramolecular nucleophilic substitution, the second hydroxyl group attacks the electron deficient carbon. Provided that there are enough carbon atoms that the angle strain is not too much, a cyclic ether can be formed.

Diols can also be converted to lactones employing the Fétizon oxidation reaction.

Vicinal diols

In glycol cleavage, the C−C bond in a vicinal diol is cleaved with formation of ketone or aldehyde functional groups. See Diol oxidation.

Geminal diols

In general, organic geminal diols readily dehydrate to form a carbonyl group. For example, carbonic acid ((HO)2C=O) is unstable and has a tendency to convert to carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). Nevertheless, in rare situations the chemical equilibrium is in favor of the geminal diol. For example, when formaldehyde (H2C=O) is dissolved in water, the geminal diol (H2C(OH)2, methanediol) is favored. Other examples are the cyclic geminal diols decahydroxycyclopentane (C5(OH)10) and dodecahydroxycyclohexane (C6(OH)12), which are stable, whereas the corresponding oxocarbons (C5O5 and C6O6) do not seem to be.

See also

- Alcohols, chemical compounds with at least one hydroxyl group

- Triols, chemical compounds with three hydroxyl groups

- Polyols, chemical compounds with multiple hydroxyl groups

- Ethylene glycol

- Glycol nucleic acid (GNA)

References

- ↑ March, Jerry (1985), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure, 3rd edition, New York: Wiley, ISBN 9780471854722, OCLC 642506595.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "diols". doi:10.1351/goldbook.D01748.

- ↑ trans-cyclohexanediol Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 3, p. 217 (1955); Vol. 28, p.35 (1948) http://www.orgsynth.org/orgsyn/pdfs/CV3P0217.pdf.

- ↑ Advantages of Synthesizing trans-1,2-Cyclohexanediol in a Continuous Flow Microreactor over a Standard Glass Apparatus Andreas Hartung, Mark A. Keane, and Arno Kraft J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 10235–10238 doi:10.1021/jo701758p.

- ↑ Blomquist, A. T.; Goldstein, Albert (1956). "1,2-Cyclodecanediol". Organic Syntheses. 36: 12. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.036.0012.

- 1 2 Werle, Peter; Morawietz, Marcus; Lundmark, Stefan; Sörensen, Kent; Karvinen, Esko; Lehtonen, Juha (2008). "Alcohols, Polyhydric". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_305.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.