| Cneoridium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Subfamily: | Amyridoideae |

| Genus: | Cneoridium Hook.f. |

| Species: | C. dumosum |

| Binomial name | |

| Cneoridium dumosum | |

| |

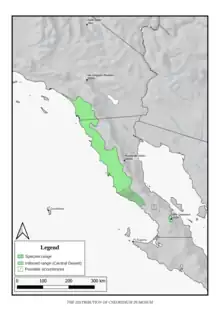

| Distribution of Cneoridium in North America | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Pitavia dumosa Nuttall | |

Cneoridium is a monotypic genus in the citrus family which contains the single species Cneoridium dumosum, commonly known as bushrue or coast spice bush. As a perennial, evergreen shrub, Cneoridium is native to the coast of southern California and Baja California, thriving in hot, dry conditions. This plant is characterized by a distinctive citrusy aroma and small, white flowers that appear from winter to spring. The flowers eventually become round berries that resemble a miniature version of the common citrus.[3]

Widely known and utilized by the indigenous peoples of the Americas for centuries, this species was first discovered and introduced to Western science by Thomas Nuttall, on his trip to San Diego. Today, this species is listed as imperiled,[1] as some of its habitats are threatened by coastal development, urbanization, military operations and fire suppression.[4] It has also found its way into horticultural circles in its native regions, providing gardeners with a low-maintenance shrub that gives off rewarding flowers.[5] Despite attractive qualities like its distinctive fragrance and flowers, this species may cause blistering and burning rashes to people after contact with its foliage, a phenomenon common with members of the citrus family, known as phytophotodermatitis.[3]

Description

This evergreen, intricately branched shrub may exceed a meter and a half in height and sprawl about as wide, with a rounded form. Its twigs are covered in small, linear to oblong-shaped green leaves 1 to 2.5 cm in length and arranged opposite of each other. The leaves are glabrous and are dotted with small glands. The inflorescence is a cyme or cluster with 1 to 3 flowers. Each flower is just over a centimeter wide with four or rarely five rounded white petals and eight yellow-anthered white stamens.[3][6]

The leaves of this plant are aromatic, while the flowers also give off a fragrance described as a "wonderful citrusy sweet perfume."[7]

The bunching fruits are round green berries about half a centimeter wide covered in a thin peel which is gland-pitted like that of a common citrus fruit. In age the berries change to a reddish to brown color. Each berry contains one or two spherical seeds.[3][6]

Phytochemistry

Numerous chemicals have been isolated from this plant, including osthol, imperatorin, isoimperatorin, bergapten, isopimpinellin, xanthotoxin, justicidin A and marmesin.[8] This plant is also capable of causing phytophotodermatitis on humans after skin contact, and it can sometimes be severe if exposure is for several hours.[9] After the plant's foliage is contacted, light-sensitizing chemicals in the oils of the plant combined with ultraviolet radiation initiate an inflammatory reaction that can present as a burning, blistering rash.[3] This effect is variable from person to person, with some people not blistering at all.[10]

Taxonomy

Taxonomic history and classification

This species was first discovered to Western science by Thomas Nuttall, an English botanist and naturalist. Nuttall had arrived in San Diego aboard the hide ship Pilgrim, staying in the harbor for three weeks as he waited for a Bryant and Sturgis ship to sail him back to Boston. Nuttall was one of few naturalists to set foot in the region at the time, being preceded by Menzies, Botta, Coulter, and Deppe, all of whom had only stopped in San Diego briefly. In Nuttall's stay in San Diego, he collected around 44 species of plants.[11] Nuttall likely encountered this species on Point Loma, as he spent extensive time on the peninsula (for it was the original anchorage in the San Diego Bay)[12] and it is home to an abundant population of this plant.[13]

From Nuttall's work, eminent North American botanists John Torrey and Asa Gray described this species as Pitavia dumosa in their Flora of North America. However, the pair had failed to find Nuttall's notes on the plant, and had to describe this species based on incomplete specimens. The botanists also noted that this species appeared to differ from the Pitavia genus as circumscribed by Jussieu.[14] Botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker later combined this species into Cneoridium dumosum,[15] but he produced a nomen invalidum (invalid name) as he failed to specify the rank.[16] Henri Ernest Baillon later corrected Hooker's mistake in 1873, with the fourth volume of his publication Histoire des Plantes, leading to the current name Cneoridium dumosum (Nutt.) Hook.f. ex Baill.[17]

The genus Cneoridium is placed in the subfamily Amyridoideae, placing it as a close relative to Amyris, its sister clade, and Stauranthus. The three genera also share morphological features, such as their fleshy fruits, characterized in this genus by the berries.[18]

Etymology

The generic name Cneoridium derives from the diminutive form of Cneorum, the spurge olive, which in turn comes from the Greek kneoron,[19] which was applied to some dwarf shrubs resembling the olive.[20][21] The first letter of Cneoridium is silent, with the name pronounced like "Nee-oh-rí-di-um."[22] The specific epithet dumosum is derived from the Latin dūmōsus, which means bushy or shrubby.[23] The common name "spice bush" likely refers to the shrub's aromatic leaves.[7]

Distribution and habitat

This species is distributed within the states of California in the United States and Baja California in Mexico. In California, this species occurs on the southern coast in San Diego and Orange counties, and on San Clemente Island.[6] In Baja California, this species is found throughout the northwestern portion of the state south to the central desert.[24] It also has a disjunct distribution in the Sierra de San Borja near Bahia de Los Angeles in southern Baja California.[25][24]

Plants of this species primarily occur on bluffs, mesa, hillsides and washes near the coast, and the slightly inland foothills of the Peninsular Ranges.[1][6] It is found in chaparral, coastal sage scrub and coastal succulent scrub habitats below 1000 meters.[3] This plant is considered to play an important role in the habitat for the San Quintin Quail (Callipepla californica subsp. plumbea).[26]

Uses

Cultivation

Introduced into cultivation by Theodore Payne,[13] this diminutive woody shrub has a reputation of being difficult to establish, but given proper care it is a long-lived, slow-growing plant that thrives on neglect.[27] Native to a large number of habitats, from the moist coast to the dry inland hills, it is adaptable to irrigation. It tolerates hot, dry climates with some afternoon shade, often staying green with no water after establishment. It may be watered sparingly during the hot season to help keep the leaves more vibrantly green. It is also recommended to keep plants away from pathways because of the risk of phytophotodermatitis triggered by the foliage.[10]

Although more commonly grown by nurseries for habitat restoration, bushrue can be utilized in local native gardens, with their moderate size compatible with small gardens. It often goes dormant in summer, with the leaves becoming dull green, and in the fall or winter they may turn yellow or orange with frost.[10] This plant will frequently bloom in winter to spring, with rewarding January flowers.[5]

This plant can be propagated by cuttings or seed. Cuttings must be taken in winter or spring from stems at least 1 year old, and treated with rooting hormone after the foliage is removed from the bottom half of the cutting. Cuttings are then placed in a mix of half peat and half moist perlite, watered, and situated in a plastic bag that is not entirely sealed. The plastic bag is then placed in a warm spot with indirect sunlight.[28] To propagate from seed, berries must be picked when they are a distinctive chocolate-brown color at the end of summer. Seed germination rates can approach 100% when they are also stratified at 55 °F for a couple of weeks.[29]

Ethnobotany

This species was utilized for medicinal purposes by the indigenous Luiseño and Kumeyaay peoples for centuries. The Luiseño would make an infusion by boiling the leaves of this plant, noting that it had a blood-thinning effect that included diuretic action.[30] They would also use it to cure earaches, by placing the raw leaves in the ear with a small amount of warm olive oil.[31] Delfina Cuero of the Kumeyaay people reported using the boiled plant as a mouthwash and gargle, and also for toothaches.[32]

Gallery

Flowering in habitat

Flowering in habitat Flowers with berries

Flowers with berries The unripe red and green berries

The unripe red and green berries Flowers with foliage

Flowers with foliage The berries, after turning brown in the summer sun

The berries, after turning brown in the summer sun

See also

- Cneoridium dumosum (Nuttall) Hooker F. Collected March 26, 1960, at an Elevation of about 1450 Meters on Cerro Quemazón, 15 Miles South of Bahía de Los Angeles, Baja California, México, Apparently for a Southeastward Range Extension of Some 140 Miles (the lengthy title of a very short humorous scientific paper about Cneoridium)

- Ceanothus verrucosus – A similarly imperiled species that occurs in the same maritime chaparral habitat.

- Arctostaphylos glandulosa subsp. crassifolia – An endangered shrub that also inhabits the southern maritime chaparral.

References

- 1 2 3 "Cneoridium dumosum". NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. 2022. Archived from the original on 2020-09-21. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ "Cneoridium dumosum". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rebman, Jon P.; Roberts, Norman C. (2012). Baja California Plant Field Guide. San Diego: Sunbelt Publications. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-916251-18-5.

- ↑ Comer, P.; Keeler-Wolf, T.; Reid, M.S. (2021). "California Maritime Chaparral". NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Archived from the original on 2022-01-23. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- 1 2 Tschudy, Clayton (2020-02-01). "GOING WILD WITH NATIVES: Bush Rue". SD Hort News. San Diego Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 2020-09-23. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Woodruff, Lindsay P.; Shevock, James R. (2012). "Cneoridium dumosum". Jepson eFlora. Jepson Flora Project. Archived from the original on 2015-12-20. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- 1 2 Fillius, Margaret (December 2015). "Plant of the Month - Coast Spice Bush" (PDF). Torreyana. Del Mar, California: Torrey Pines Docent Society: 7.

- ↑ Dreyer, David L.; Lee, Alson (1969-08-01). "Constituents of Cneoridium dumosum (Nutt.) Hook. F." Phytochemistry. 8 (8): 1499–1501. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)85920-8. ISSN 0031-9422.

- ↑ Tunget, C L; Turchen, S G; Manoguerra, A S; Clark, R F; Pudoff, D E (1994-12-01). "Sunlight and the plant: a toxic combination: severe phytophotodermatitis from Cneoridium dumosum". Cutis. 54 (6): 400–402. ISSN 2326-6929. PMID 7867382.

- 1 2 3 Gordon, Lee (8 January 2022). "Overlooked Native Plants for the Garden Bush rue (Cneoridium dumosum)". California Native Plant Society-San Diego Chapter. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ Beidleman, Richard G. (2006). California's Frontier Naturalists. University of California Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-520-23010-1.

- ↑ Lightner, James (17 November 2015). Scientists on the La Playa Trail, 1769-1851 (PDF). Point Loma: La Playa Trail Association.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 "Cneoridium dumosum". Native Plant Database. Theodore Payne Foundation. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ Torrey, John; Gray, Asa (1838). A flora of North America :containing abridged descriptions of all the known indigenous and naturalized plants growing north of Mexico, arranged according to the natural system. New York: Wiley & Putnam. pp. 215–216. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.9466.

- ↑ Hooker, Joseph Dalton; Bentham, George (1862). Genera Plantarum ad exemplaria imprimis in herbariis Kewensibus. Vol. 1.

- ↑ "Cneoridium dumosum Hook.f." International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ↑ "Cneoridium dumosum (Nutt.) Hook.f. ex Baill". International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ↑ Appelhans, Marc S.; Bayly, Michael J.; Heslewood, Margaret M.; Groppo, Milton; Verboom, G. Anthony; Forster, Paul I.; Kallunki, Jacquelyn A.; Duretto, Marco F. (2021). "A new subfamily classification of the Citrus family (Rutaceae) based on six nuclear and plastid markers". Taxon. 70 (5): 1035–1061. doi:10.1002/tax.12543. hdl:11343/288824. ISSN 1996-8175. S2CID 237693195.

- ↑ Simpson, Michael G. "Cneoridium dumosum". Plants of San Diego County, California. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 2001-02-13. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ↑ "Cneorum - Trees and Shrubs Online". Trees and Shrubs Online. International Dendrology Society. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

...the Greek 'kneoron', applied to some dwarf shrub resembling the olive and with acrid leaves (perhaps Daphne gnidium).

- ↑ "Page CI-CY". CalFlora. Archived from the original on 2006-03-12. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

Cneorid'ium: a diminutive of Cneorum, spurge olive, from the Greek kneoron, for some shrub resembling the olive. The genus Cneoridium was published by Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1862. (ref. genus Cneoridium)

- ↑ Simpson, Michael G. "How to Pronounce Scientific Names". Plant Systematics Resources. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 2011-12-22. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ↑ "Charlton T. Lewis, An Elementary Latin Dictionary, dūmōsus (dumm-)". Perseus. Tufts University. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- 1 2 Rebman, J. P.; Gibson, J.; Rich, K. (2016). "Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California, Mexico" (PDF). San Diego Society of Natural History. 45: 251.

This common native shrub occurs mostly in nw BC but ranges into the northern CD region and is disjunct to the SBOR in s BC.

- ↑ Moran, Reid (1962). "Cneoridium dumosum (Nuttall) Hooker F. Collected March 26, 1960, at an Elevation of about 1450 Meters on Cerro Quemazón, 15 Miles South of Bahía de Los Angeles, Baja California, México, Apparently for a Southeastward Range Extension of Some 140 Miles". Madroño. 16: 272.

- ↑ Vanderplank, Sula (2011). Quail-Friendly Plants of Baja California: an Exploration of the Flora of the Santo Tomás, San Vicente, San Jacinto, and San Quintín Valleys, Core Habitat for the California Quail (Callipepla californica var. plumbea). Claremont, California: Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden. p. 50. ISSN 1094-1398.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Wilson, Bert (2012). "Cneoridium dumosum - BerryRue". Las Pilitas, Nature of California. Las Pilitas Nursery. Archived from the original on 2015-07-30. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ "Bush Rue, Cneoridium dumosum". Calscape. California Native Plant Society. Archived from the original on 2017-12-27. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ Gordon, Lee (October 2, 2018). "Some Native Seeds Require Sun to Germinate". California Native Plant Society-San Diego Chapter. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ Crouthamel, Steven J. "Luiseno Ethnobotany". Palomar College. Archived from the original on 2012-08-09. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ "Plant Details :: Bush-rue". CSU San Marcos Anthropology Ethnobotany Database. Cal State San Marcos. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ↑ Cuero, Delfina; Shipek, Florence C. (1991). Delfina Cuero: Her Autobiography - An Account of Her Last Years and Her Ethnobotanic Contributions. Ballena Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0879191221.