College Park, Maryland | |

|---|---|

Flag  Seal | |

| |

College Park Location in Maryland  College Park College Park (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 38°59′48″N 76°55′39″W / 38.99667°N 76.92750°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Founded | 1856 |

| Incorporated | 1945 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[1] |

| • Mayor | S.M. Fazlul Kabir |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.68 sq mi (14.72 km2) |

| • Land | 5.61 sq mi (14.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.18 km2) |

| Elevation | 69 ft (21 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 34,740 |

| • Density | 6,191.41/sq mi (2,390.37/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 20740–20742 |

| Area code | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-18750 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2390578 |

| Website | www.collegeparkmd.gov |

College Park is a city in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States,[3] located approximately four miles (6.4 km) from the northeast border of Washington, D.C. Its population was 34,740 at the 2020 United States census. It is the home of the University of Maryland, College Park.

College Park is also home to federal agencies such as the National Archives at College Park (Archives II), NOAA's Weather Prediction Center,[4] and the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition,[5] as well as tech companies such as IonQ (quantum computing)[6] or Cybrary (cyber security).[7]

College Park Airport, established in 1909, is the world's oldest continuously operated airport. The College Park Aviation Museum, attached to the airport and an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, houses antique and reproduction aircraft as well as materials relating to early aviation history.[8]

In 2014 the University of Maryland launched the Greater College Park initiative, a $2 billion public-private investment to revitalize the community around the university, develop a robust Discovery District and create one of the nation’s best college towns.[9][10] As a result, the city is experiencing significant development that has led to new housing, office space, schools, grocery stores, restaurants, and other amenities.[11][12][13]

History

The earliest evidence of human activity in the College Park area was found at an archeological site just south of Archives II. Projectile points of Clagett and Vernon styles dating from 3000 to 2600 B.C. were recovered, a notable find given their location away from a river. This finding together with other similar ones indicate that the native American population became more sedentary in the Late Archaic period as the availability of local food supply increased, and social complexity grew. By the time Europeans first arrived and colonized the region in the early 17th century, the various native American groups had aligned themselves into a chiefdom under the Piscataway people.[14]

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the European settlers lived on large plantations, some holding the original grants under Lord Baltimore. In College Park, there are records for Toaping Castle, a land grant to Col. Isaac Walker from about 1745 in the area between Branchville, Greenbelt, and Berwyn Heights, and for the Calvert family's Riversdale, which included parts of South College Park.[15] One of the oldest buildings in the city, the Old Parish House dating from 1817 was initially a farm building in the latter estate.[16]

19th century

The oldest standing building in College Park is the Rossborough Inn, whose construction began in 1798 and was completed in 1812. The forerunner of today's University of Maryland was chartered in 1856 as the Maryland Agricultural College, and would become a land grant college in February 1864.

The original College Park subdivision was first platted in 1872 by Eugene Campbell. Early maps called the local post office "College Lawn".[17] The area remained undeveloped and was re-platted in 1889 by John O. Johnson and Samuel Curriden, Washington real estate developers. The original 125-acre (0.51 km2) tract was divided into a grid-street pattern with long, narrow building lots, with a standard lot size of 50 feet (15 m) by 200 feet (61 m). College Park originally included single-family residences constructed in the Shingle, Queen Anne, and Stick styles, as well as modest vernacular dwellings.

By the turn of the century College Park was being developed rapidly, catering to those who were seeking to escape the crowded Washington, D.C., as well as to a rapidly expanding staff of college faculty and employees.

20th century

In 1909 the College Park Airport was established by the United States Army Signal Corps to serve as a training location for Wilbur Wright to instruct military officers to fly in the US government's first airplane. Civilian aircraft began flying from College Park Airport as early as December 1911, making it the world's oldest continuously operated airport.[18]

Commercial development in the city increased in the 1920s, aided by the increased automobile traffic and the growing campus along Baltimore Avenue/Route 1. By the late 1930s, most of the original subdivision had been partially developed. Several fraternities and sororities from the University of Maryland built houses in the neighborhood. After World War II, construction consisted mostly of infill of ranch and split-level houses. After incorporation in 1945, the city continued to grow, and a municipal center was built in 1959.[19]

The Lakeland neighborhood was developed beginning in 1890 around the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, whose Branchville and Calvert Road depots were located approximately one mile to the north and south, respectively. Lakeland was created by Edwin Newman, who improved the original 238 acres (0.96 km2) located to the west of the railroad. He also built a number of the original homes, a small town hall, and a general store. The area was originally envisioned as a resort-type community. However, due to the flood-prone, low-lying topography, the neighborhood became an area of African-American settlement. Around 1900, the Baltimore Gold Fish Company built five artificial lakes in the area to spawn goldfish and rarer species of fish. By 1903 Lakeland was an established African-American community with a school and two churches. Lakeland was central in a group of African American communities located along Route One through Prince Georges County. Lakeland High School opened in 1928 with funding from the Rosenwald Fund, the African American community and the county. Lakeland High served all African American students in the northern half of the county until 1950 when it was converted to a facility for lower grades. The community's first Rosenwald school was a new elementary which opened in 1925.[20]

The Berwyn neighborhood was developed beginning about 1885 adjacent to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. It was created by Francis Shannabrook, a Pennsylvanian who purchased a tract of land between Baltimore Avenue and the railroad tracks. Shannabrook established a small depot, built a general store, and erected approximately 15 homes in the area to attract moderate-income families looking to move out of Washington. The neighborhood began to grow after 1900 when the City and Suburban Electric Railway entered the area. By 1925, approximately 100 single-family homes existed, mostly two-story, wood-frame buildings. The community housing continued to develop in the 1930s and 1940s with one story bungalows, Cape Cods, and Victorians and, later, raised ranches and split-level homes.[19]

The Daniels Park neighborhood was developed, beginning in 1905 on the east and west sides of the City and Suburban Electric Railway in north College Park. Daniels Park was created by Edward Daniels on 47 acres (19 ha) of land. This small residential subdivision was improved with single-family houses arranged along a grid pattern of streets. The houses—built between 1905 and the 1930s—range in style from American Foursquares to bungalows.[19]

The Hollywood neighborhood was developed in the early 20th century along the City and Suburban Electric Railway. Edward Daniels, the developer of Daniels Park, planned the Hollywood subdivision as a northern extension of that earlier community. Development in Hollywood was slow until after World War II, when Albert Turner acquired large tracts of the northern part of the neighborhood in the late 1940s. Turner was able to develop and market brick and frame three-bedroom bungalows beginning in 1950. By 1952, an elementary school had been built. Hollywood Neighborhood Park, a 21-acre (8.5 ha) facility along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line, is operated by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission.[19]

In 1943, due to World War II efforts to conserve rail transport, the Washington Senators relocated their spring training camp to College Park. The locations of 1943 Major League Baseball spring training camps were limited to an area east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio River.[21]

During the 1960s through the 1980s an Urban Renewal Project took place within the historic African American community of Lakeland. This project was carried out in the face of the opposition of the community's residents and resulted in the redevelopment of approximately two thirds of the community. It displaced 104 of Lakeland's 150 households.[20][22]

The College Park–University of Maryland station opened in 1993, connecting College Park to Washington D.C. by means of Metro. During its construction in the late 1980s, sand and gravel were excavated from the site of an adjacent small lake. In return, Metro built Lake Artemesia on the site, a large recreational area that includes aquatic gardens, fishing piers, and hiker-biker trails.

21st century

By the turn of the 21st century, College Park began experiencing significant development pressure. Both students and city residents acknowledged the city's lack of amenities and poor sense of place. In 2002, the city and county passed the Route 1 Sector Plan, which allowed and encouraged mixed use development along College Park's main roadway. In July 2006, a group of students created Rethink College Park—a community group providing a website to share information about development and to encourage public dialogue. Early mixed-used projects along Baltimore Avenue included the View I (2006) and II (2010), Mazza Grandmarc (2010), and the Varsity (2011).

Development accelerated after Wallace Loh became the president of the University of Maryland in 2010 and relations between the university and the city improved.[23] It was recognized that the university could not compete if the students, faculty, and staff could not live in College Park[24] so the Greater College Park initiative, a $2 billion public-private investment to revitalize the community around the university aiming to create one of the nation’s best college towns, was launched in 2014.[9] Some of the developments that occurred as a result of this and other initiatives, include

- The creation of the preparatory school College Park Academy in 2013.

- The launch of the Discovery District, the university's business and research park.[25][26][12]

- The 4-star Hotel at UMD (2017) and the Cambria (2018), the first hotels built in the city in over half a century.[23]

- The development of the College Park City Hall (2021), a joint venture between the city and the university providing offices for both as well as retail space and a public plaza.[27]

- The construction of a series of mixed-used apartment high-rises[28][29] such as Domain (2014), Landmark (2015), Terrapin Row (2016), Alloy (2019), Nine (2022), Tempo (2022), Aster (2022), Aspen Heights (2023), Standard (2023), or Hub (2023) that brought along key amenities such as new grocery stores.[13]

This development has been complemented by two major infrastructure projects: the Purple Line, which will provide direct light-rail connections form College Park to Bethesda, Silver Spring, and New Carrolton, and the reconstruction of a portion of Baltimore Avenue into a boulevard with a planted median, new bicycle lanes, and continuous sidewalks.[30] Additionally, the University of Maryland has added several state-of-the-art facilities on their campus, including the Iribe Center for computer science and engineering,[31] the Thurgood Marshall Hall for the public policy school,[32] and the IDEA factory for engineering and entrepreneurship.[33]

On June 9, 2020, the city government passed a "Resolution of the Mayor and Council of the City of College Park Renouncing Systemic Racism and Declaring Support of Black Lives" which recognized harm done to the historic African American community of Lakeland. In it, "the Mayor and Council acknowledge and apologize for our city's past history of oppression, particularly with regards to the Lakeland community, and actively seek opportunities for accountability and truth-telling about past injustice, and aggressively seek opportunities for restorative justice".[34]

On March 2, 2023, Patrick Wojahn, who had served as College Park's mayor since 2015, resigned after being arrested on child pornography charges.[35] Wojahn pleaded guilty to over 100 counts and was sentenced to 150 years with 120 years suspended. [36]

On November 8, 2023 the parking lot on the Greenbelt Metro station, adjacent to North College Park, was selected to host the future FBI headquarters.[37] The construction of this facility is expected to further accelerate and consolidate the development of College Park.[38]

Geography

College Park is located along the Northeast branch of the Anacostia river, a tributary of the Potomac river that flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The city is in Prince George's County, Maryland and is also part of the Washington metropolitan area. It is bordered to the North by Beltsville, to the East by Berwyn Heights, to the South by Riverdale Park and University Park, and to the West by Hyattsville and Adelphi.

College Park has a total area of 5.68 square miles (14.71 km2), of which 5.64 square miles (14.61 km2) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2) is water.[39]

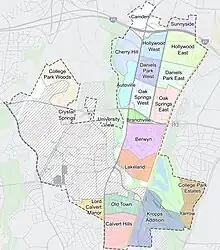

Neighborhoods

- Acerdale

- Autoville

- Berwyn

- Branchville

- Calvert Hills

- Camden

- Cherry Hill

- College Park Estates

- College Park Woods

- Crystal Springs

- Daniels Park

- Hollywood

- Lakeland

- Lord Calvert Manor

- Oak Springs

- Old Town

- Sunnyside

- Yarrow

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, College Park has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[40]

Tornadoes are rare (the whole state of Maryland averages 4 tornadoes per year[41]), but on September 24, 2001, a multiple-vortex F3 tornado hit the area, causing two deaths and 55 injuries and $101 million in property damage. This tornado was part of the Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., tornado outbreak of 2001, one of the most dramatic recent tornado events to directly affect the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 45 (7) |

48 (9) |

57 (14) |

68 (20) |

76 (24) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

86 (30) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

58 (14) |

49 (9) |

67 (19) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36 (2) |

38 (3) |

46 (8) |

56 (13) |

65 (18) |

74 (23) |

79 (26) |

77 (25) |

69 (21) |

57 (14) |

48 (9) |

40 (4) |

58 (14) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 29 (−2) |

30 (−1) |

37 (3) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

69 (21) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

39 (4) |

33 (1) |

49 (9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.2 (56) |

2.2 (56) |

3.1 (79) |

3.3 (84) |

3.5 (89) |

3.4 (86) |

3.2 (81) |

3.2 (81) |

3.4 (86) |

3.3 (84) |

3.1 (79) |

2.8 (71) |

36.7 (930) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.4 (11) |

5.0 (13) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.3 (5.8) |

13.6 (35) |

| Percent possible sunshine | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 54 | 58 | 62 | 63 | 63 | 56 | 49 | 57 |

| Source: Weather Spark [42] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 11,170 | — | |

| 1960 | 18,482 | 65.5% | |

| 1970 | 26,156 | 41.5% | |

| 1980 | 23,614 | −9.7% | |

| 1990 | 21,927 | −7.1% | |

| 2000 | 24,657 | 12.5% | |

| 2010 | 30,413 | 23.3% | |

| 2020 | 34,740 | 14.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[43] | |||

The median income for a household in the city was $50,168, and the median income for a family was $62,759 (these figures had risen to $66,953 and $82,295 respectively as of a 2007 estimate[44]). Males had a median income of $40,445 versus $31,631 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,026. About 4.2% of families and 19.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.9% of those under age 18 and 9.2% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census[45] of 2010, there were 30,413 people, 6,757 households, and 2,852 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,392.4 inhabitants per square mile (2,082.0/km2). There were 8,212 housing units at an average density of 1,456.0 per square mile (562.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 63.0% White, 14.3% African American, 0.3% Native American, 12.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 6.0% from other races, and 3.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 11.9% of the population.

There were 6,757 households, of which 18.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 30.6% were married couples living together, 7.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 57.8% were non-families. 24.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.79 and the average family size was 3.18.

The median age in the city was 21.3 years. 7.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 60.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 15.7% were from 25 to 44; 11% were from 45 to 64; and 5.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 53.1% male and 46.9% female.

2000 census

As of the census[46] of 2000, there were 24,657 people, 6,030 households, and 3,039 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,537.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,751.9/km2). There were 6,245 housing units at an average density of 1,149.2 per square mile (443.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 68.82% White, 15.93% Black or African American, 0.33% Native American, 10.03% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 2.57% from other races, and 2.31% from two or more races. 5.54% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 6,030 households, out of which 19.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.6% were married couples living together, 8.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 49.6% were non-families. 25.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.65 and the average family size was 3.11.

In the city, 10.5% of the population was under the age of 18, 51.3% was between from 18 to 24, 19.8% from 25 to 44, 11.3% from 45 to 64, and 7.2% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females, there were 110.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 111.2 males.

Economy

The University of Maryland shapes College Park's economy significantly, contributing to over half of the city's total employment and a significant fraction of its population. In 2017 the university rebranded its 150-acre business and research park as the Discovery district[47] aiming to bring together research firms, start-ups and shops and restaurants.[48] This area is divided between College Park and Riverdale Park.

This Discovery district is home to federal agencies such as the NOAA's Weather Prediction Center,[4] the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN),[5] and the navy's software factory (the Forge),[49] as well as technology companies generally related to the university.

An area that has recently seen rapid growth in the Discovery district is quantum technology. Efforts in this field include IonQ,[6] a quantum computing company with a market capitalization of $2.8 billion as of December 2023,[50] Quantum Startup Foundry,[51] Quantum Catalyzer,[52] and the National Quantum Lab at Maryland (Q-Lab), the nation’s first facility providing hands-on access to a commercial-grade quantum computer to the scientific community.[53][54]

Other sectors with a strong presence in the Discovery district are cyber security (Cybrary, Immuta, BlueVoyand, and Inky) and medical devices (Medcura).[55] On December 18, 2023, the Washington Commanders announced that they would be moving their headquarters to the Discovery district in 2024.[56]

Top employers

According to the city's 2022 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[57] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Employees | Total city employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | University of Maryland, College Park | 14,505 | 50.2% |

| 2 | University of Maryland Global Campus | 3,466 | 11.9% |

| 3 | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | 805 | 2.8% |

| 4 | Food and Drug Administration | 714 | 2.5% |

| 5 | National Archives and Records Administration | 674 | 2.3% |

| 6 | IKEA | 460 | 1.6% |

| 7 | The Home Depot | 168 | 0.6% |

| 8 | American Center for Physics | 142 | 0.5% |

| 9 | College Park Hyundai | 138 | 0.5% |

| 10 | The Hotel at the University of Maryland | 115 | 0.4% |

Culture

The city organizes several annual events. The College Park Day, held in October at the College Park Aviation Museum & Airport, is the city's signature event.[58] It features various activities, entertainment, and food vendors celebrating the community. Other events include the College Park Parade, featuring local groups, organizations, entertainers, and performers,[59] Friday Night Live!, held several Fridays over the summer and featuring a variety of musical genres, food, beer, and other entertainment,[60] and Winter Wonderland, which hosts the annual Winter Wonderland holiday market and the lighting of the city's tree.[61]

During the late spring and throughout the summer, farmer markets in the Hollywood neighborhood,[62] the university campus,[63] and Paint Branch Parkway sell local produce, meats, bakery products, and crafts.

Friday Night Life! at the City Hall plaza

Friday Night Life! at the City Hall plaza Entrance at the College Park day

Entrance at the College Park day Inflatable at the College Park day with the airport in the back

Inflatable at the College Park day with the airport in the back Tree lighting at the Winter Wonderland

Tree lighting at the Winter Wonderland Grinch at the College Park Winter Wonderland

Grinch at the College Park Winter Wonderland

Performing arts

Several performing arts groups and facilities are on the University of Maryland's campus. The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center is a 318,000-square-foot complex that opened in 2001 housing six performance venues as well as the Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library. The Adele H. Stamp Student Union houses the Hoff Theater, the Art and Learning Center, and the Grand Ballroom where various events are held. Additionally, the Nyumburu Amphitheater, adjacent to the Stamp Student Union, features outdoor performances.[64]

Other venues in College Park that host cultural events include the Old Parish House,[65] owned by the city, and the Hall CP, a restaurant with an outdoor performing area.[66][67]

Museums

The College Park Aviation Museum is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution that since 1987 has housed antique and reproduction aircraft associated with the history of College Park Airport. It also includes an extensive library and archives which hold materials relating to the airport's history, early aviation history, especially relating to Maryland.

Other museums in College Park include the Art Gallery at the University of Maryland, the flagship art museum on the campus of the University of Maryland, and the National Museum of Language, a cultural institution established in 1997 to examine the history, impact, and art of language.

Historic sites

The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission has identified a total of 16 historic sites in College Park.[16] The following is a list of the historic sites that predate the 20th century

| Site name | Year | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Archives Archeological Site | 4000-1500 B.C. | 8601 Adelphi Rd | Archeological remains from prehistoric settlements during the Late Archaic period. |

| Rossborough Inn | 1803 | 7682 Baltimore Ave | Owned by the Calverts of Riversdale, the inn was a popular stage-stop on the Baltimore and Washington Turnpike. |

| Old Parish House | 1817 | 4711 Knox Rd | Originally constructed as a farm building on the Calverts’ Riversdale estate, later was used as a parish hall and the headquarters of the College Park Woman’s Club. |

| Cory House | 1891 | 4710 College Ave | One of the first houses built in the 1889 subdivision of College Park. |

| Morrill Hall | 1892 | 7313 Preinkert Dr | Named for Justin Smith Morrill, a Vermont politician who wrote the first Land Grant Act. |

| Taliaferro House | 1893 | 7406 Columbia Ave | The home of Emily Taliaferro, daughter of John Oliver Johnson who developed the 1889 College Park subdivision. |

| Lake House | 1894 | 8524 Potomac Ave | Built by and for the family of Wilmot Lake, later served as the parsonage of the Berwyn Presbyterian Church. |

| McDonnell House | 1896 | 7400 Dartmouth Ave | Built for Henry B. McDonnell, the first Dean of Arts and Sciences of the University of Maryland. |

The Rossborough Inn (1803), oldest standing building in College Park

The Rossborough Inn (1803), oldest standing building in College Park The Old Parish House, built in 1817

The Old Parish House, built in 1817 The Cory House, built in 1891

The Cory House, built in 1891 The Lake House, built in 1894

The Lake House, built in 1894 The McDonnell House, built in 1896

The McDonnell House, built in 1896

Additionally, the Calvert Hills Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002,[68] and Old Town College Park in 2006.

Sports and recreation

The sport culture in College Park centers around the 20 men's and women's sports teams fielded by the University of Maryland. These teams compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Big Ten Conference and have won over 44 national championships.[69][70] In 2008 and 2010, The Princeton Review named the University of Maryland's athletic facilities the best in the nation.[71][72] The largest of these facilities are the SECU Stadium for football and lacrosse (capacity 51,802), the XFINITY Center for basketball (capacity 17,950), and the Ludwig Field for soccer (capacity 7,000).

College Park offers 11 parks maintained by the city and the Maryland-national capital park & planning commission.[73] The most popular is Lake Artemesia, a 38-acre lake that includes aquatic gardens, fishing piers, and a 1.35 mile hiker-biker trail around the lake. The lake is considered to provide one of the best inland aquatic habitats in the DC suburban area for birds, hosting over 220 species.[74] The trail around the lake connects to other heavily-used trails within the city that are part of the Anacostia Tributary Trail System and the East Coast Greenway, making College Park a regional activity hub.[75] Other parks in the city include the Hollywood Gateway Park, a pocket park in North College Park that opened in 2020,[76] and the Paint Branch Community Park which offers an 18-hole disc golf course.[77]

Runners and walkers from College Park and nearby communities gather most Saturdays for the College Park parkrun,[78][79] a timed 5-kilometre (3.1 mi) event. With over 39,000 finishes, the College Park parkrun is estimated to be the largest event of its kind in the US.[80]

Other city attractions include the Junior Tennis Champions Center (JTCC), a tennis training center and preparatory school where top-10 player Frances Tiafoe was raised, the War Veterans Memorial,[81] the Ellen E. Linson Splash Park,[82] featuring slides, diving boards, and lap lanes, and the Herbert Wells Ice Rink, a semi-enclosed seasonal ice rink in the same facility.[83]

City government

College Park has operated under the council-manager form of government since 1960. The City Council is the legislative body of the City and makes all city policy. The council has eight members, representing four districts in the city. The Council is elected by district every 2 years in non-partisan elections. The Mayor is elected at large on the same election schedule as the City Council. City Council meetings are held weekly at the College Park City Hall. The mayors of College Park have been:[84]

- William A. Duvall (1945–1951)

- Charles R. Davis (1951–1963)

- William W. Gullett (1963–1969)

- William R. Reading (1969–1973)

- Dervey A. Lomax (1973–1975)

- St. Clair Reeves (1975–1981)

- Alvin J. Kushner (1981–1987)

- Anna Latta Owens (1987–1993)

- Joseph E. Page (1993–1997)

- Michael J. Jacobs (1997–2001)

- Stephen A. Brayman (2001–2009)

- Andrew M. Fellows (2009–2015)

- Patrick L. Wojahn (2015–2023)

- Denise C. Mitchell, Acting (2023)

- S.M. Fazlul Kabir (2023–present)

The Council appoints the City Manager, who manages all city services, implements the policy established by the City Council, and appoints and supervises the heads of the various city department. The City Manager also serves as an adviser to the City Council. The manager’s office manages the day-to-day activities and financial affairs of the City, and oversees communications and IT for the City.[85]

The government of College Park has five operating functions:[57] General Government and Administration; Public Services, Planning and Community Development; Youth, Family and Senior Services; and Public Works. In addition to the Finance Department, the General Government and Administration function includes the offices/departments of the City Manager, Economic Development, City Clerk, Human Resources, City Attorney, Communications and Information Technology.

The Prince George's County Police Department District 1 Station in Hyattsville serves College Park.[86] The U.S. Postal Service operates the College Park Post Office and the North College Park Post Office.[87][88] The College Park Volunteer Fire Department responds to emergencies in the University of Maryland, City of College Park and northern Prince George’s County areas.[89]

As of March 2023, College Park belongs to Maryland's 4th congressional district.

City-student politics

Like many college towns, College Park has had its share of political controversy. Occasionally, University of Maryland students plan voter registration drives and seek to elect one of their own to the city council. City residents, including students living within the city are eligible[90] to run for city council if they are at least 18 years of age. Several attempts at student representation across two decades were unsuccessful until Marcus Afzali won a seat in 2009.

- 1993 – Dana L. Loewenstein & Michael J. Moore – Perhaps the most controversial of all student races was that of Loewenstein, a former president of the Panhellenic Association, the sorority umbrella organization at the university. A year after she had lost the election, she was charged with 16 counts of perjury, 16 counts of aiding and advising to falsely register voters and faced a maximum prison sentence of over 200+ years. Ms. Loewenstein's opponent in the council race, Michael Smith, joined former council member Chester Joy in filing a complaint with the Prince George's County Board of Elections days before the Nov 2 election in an effort to intimidate students from voting. The complaint alleged that 16 of her sorority pledges lived in one district but registered in another. The complaint was turned over to the state's attorney, who filed criminal charges against Loewenstein a year after she lost the election, despite no student voting illegally. The complaint alleged that all of the pledges lived in on-campus dorms but used the house address as their residence. Loewenstein was found not guilty by the Circuit Court.

- 2001 – Mike Mann & Daniel Dorfman – In November 2001, Michael Mann[91] and Daniel Dorfman, sought the two District 3 seats on the College Park City Council. Campaigning against incumbent Eric Olson and for an open seat created by then-councilman Brayman's decision to run for mayor, the two campaigned heavily to inform students there was a council race going on that year, and registered over 700 students to vote in the municipal election. Despite their hard work and an almost year-long campaign, they were defeated.

- 2007 – Nick Aragon – In January 2007, Nick Aragon lost a special election for the city council. Two incumbents created a vacancy when they were elected to higher county offices. In turn, the city was forced to hold a special election after the November 2006 elections. The city chose an election date during the university's winter recess, a time when many students were away from the city. With some help from the Student Government Association (SGA)[92] and an endorsement by College Park Mayor Steve Brayman, the Aragon campaign encouraged students to use absentee ballots, although few actually did, and Aragon lost the election.

- 2009 – Marcus Afzali – A 24-year-old doctoral student in the Department of Government and Politics at UMD, Afzahli won a seat on the city council representing District 4 in November 2009. He attributed displays of "energy"—exemplified by taking time to knock on doors and reach out to residents—as the cause behind his success. The 2009 election is notable not only for Afzali's performance at the polls, but for the fact that both District 4 incumbents lost.[93][94]

Transportation

_between_Exit_23_and_Exit_25_in_College_Park%252C_Prince_George's_County%252C_Maryland.jpg.webp)

Roads and highways

The most prominent highway serving College Park is Interstate 95/Interstate 495, the Capital Beltway. I-495 encircles Washington, D.C. via the Capital Beltway, providing access to the city and its many suburbs. I-95 only follows the eastern portion of the beltway, diverging away from the beltway near its northeasternmost and southwesternmost points. To the north, I-95 passes through Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City and Boston on its way to Canada, while to the south, it traverses Richmond on its way to Florida.

Primary access to College Park from I-95/I-495 is provided via an interchange with U.S. Route 1, which traverses downtown College Park along Baltimore Avenue. Maryland State Route 193 also passes through the city, following University Boulevard and Greenbelt Road from west to east. MD 431 also serves College Park, linking it with Riverdale Park.

Airport

College Park Airport is the oldest continuously operating airport in the United States and is one of the oldest airports in the world, having been in continuous operation since 1909. It originated as the site where the U.S. government began to train pilots, under the tutelage of Wilbur Wright, for military purposes. Its future status is uncertain, as it lies just a few miles outside the restricted airspace of Washington, D.C. In 1977, the airport was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[95]

Area commercial airports include Baltimore-Washington International Airport, Reagan National Airport, and Washington Dulles International Airport.

Public transportation

College Park–University of Maryland Station on the Washington Metro's Green Line is in College Park; a large commuter parking garage was completed in 2004 adjacent to the Metro station. MARC trains run on CSX tracks adjacent to the Green Line and stop at a small station next to the College Park Metro station. The Metro station lies at what had been the historic junction of Calvert Road and the CSX tracks.

College Park had streetcar service from 1903 to 1962 along what is now Rhode Island Avenue and the College Park Trolley Trail.

College Park will also have three Purple Line light rail stations when the system opens in 2026.[96] These will be the Campus Center station, East Campus station, and a station connected to the existing College Park-University of Maryland Metro station. The Purple Line will link the Metro's Red, Green, and Orange lines. As well as the MARC commuter rail's Penn and Camden lines. The Purple Line station on the University of Maryland campus will eliminate the need for a bus route to the university's main Metro station, the Green line's College Park – U of Md station.[97]

Media

- UMTV (University of Maryland)

- WMUC broadcasts from the University of Maryland campus, with a range of two miles (3 km) – roughly from the campus to the Beltway. It is also broadcast over the internet at www.wmucradio.com.[98]

- The Diamondback, a student publication, formerly distributed once a week on a limited basis downtown, including in city hall, and widely on the campus of the University of Maryland. Print editions were discontinued in March 2020, and the newspaper was moved entirely online.

- College Park: Here & Now, which began publishing in 2020, is a free monthly nonprofit newspaper available throughout the city.[99]

- The oldest operational Persian podcast is called Radio College Park as it is produced by a group of Iranian graduate students at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The city is part of the Washington, D.C. television market (DMA #9).

Education

Colleges and universities

The University of Maryland, College Park, the flagship institution of the University System of Maryland, is located within the College Park city limits.

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools

College Park is served by Prince George's County Public Schools. The city is zoned to several different schools.[100]

Elementary school students are zoned to:[101]

- Hollywood Elementary School (in College Park)

- Paint Branch Elementary School (in College Park)

- Berwyn Heights Elementary School (in Berwyn Heights)

- University Park Elementary School (in University Park)

- Cherokee Lane Elementary School (Adelphi CDP)

Middle school students are zoned to:[102]

- Greenbelt Middle School (in Greenbelt)

- Hyattsville Middle School (in Hyattsville)

- Buck Lodge Middle School (Adelphi CDP)

High school students are zoned to:[103]

- High Point High School (Beltsville CDP)

- Northwestern High School (Hyattsville)

- Parkdale High School (Riverdale Park)

Other area public high schools include: Eleanor Roosevelt High School (Greenbelt).[104]

PGCPS previously operated College Park Elementary School. For a period Friends Community School occupied the building, but it moved out in 2007. The nascent College Park Academy attempted to lease the previous College Park elementary building, but there was community opposition.[105] The grade 6-12 charter school currently is located in Riverdale Park.[106]

African-American schools

Prior to the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century, white and black students attended schools that were racially segregated by law. The first high school for black students in the county was Marlboro Colored High School which opened in 1923 and was located in Upper Marlboro.[107] Lakeland Elementary School, a school for black children in the Lakeland neighborhood, opened in 1925; followed by a high school for black students Lakeland High School, opened in 1928.[108] Lakeland High and Elementary were financed by the Rosenwald Fund, and therefore were Rosenwald Schools.[109] In 1935, the Marlboro Colored High School closed, and the Frederick Douglass High School was opened in a new campus, which remained segregated until approx. 1964.

In 1950, Lakeland High was replaced by Fairmont Heights High School near Fairmount Heights.[110] In turn, Lakeland Elementary School moved into the former high school building.[111] c. 1964, legal racial segregation ended in Prince George's County schools.[110]

Private schools

Private schools include:[104]

- Dar-us-Salaam/Al Huda School, K–12 (College Park)[112][113]

- Berwyn Baptist School, PreK–8

- Friends Community School, K–8

- Holy Redeemer School, PreK–8

- Laurel Springs School at Junior Tennis Champions Center, K–12

- Saint Francis International School St. Mark Campus, K–8, Hyattsville[114] – formerly St. Mark the Evangelist School,[115] closed and merged into Saint Francis International, which opened in 2010.[116]

References

- ↑ "Office of the City Manager – College Park, MD". City of College Park. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ↑ "College Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- 1 2 "NOAA Center for Weather and Climate Prediction" (PDF). National Weather Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- 1 2 Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (September 9, 2020). "Contact CFSAN". FDA. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- 1 2 "About IonQ". IonQ. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ Babcock, Stephen (May 7, 2021). "Cybrary moves into its new College Park office". Technical.ly. Technically Media. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Library". Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- 1 2 Richman, Talia (December 13, 2015). "Former College Park Mayor Andy Fellows reflects on three terms of focusing on safety, development". The Diamondback. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Universities". MPower Maryland. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ Farrell, Liam (September 14, 2021). "Getting 'Greater' in Fall 2021". Maryland Today. University of Maryland. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- 1 2 Lynch, Emily (December 2, 2022). "Discovery Point: Meet The New D.C.-Area Development That Joins Local Talent With National Business". Bisnow. Bisnow Media. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- 1 2 Krakower, Annie (October 27, 2022). "Grocery Shopping Gets 'Greater' as Trader Joe's Opens". Maryland Today. University of Maryland. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ Seidel, John L. (December 27, 2003). "Overview of the Anacostia Trails Heritage Area: prehistory to contact period" (PDF). Anacostia Trails Heritage Area.

- ↑ Burch, T. Raymond (September 2, 1965). "History and Development of the City of College Park, Berwyn Heights, Greenbelt, and Adjacent Areas". Educational Web Sites on Astronomy, Physics, Spaceflight and the Earth's Magnetism.

- 1 2 Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (April 1, 2011). "Illustrated Inventory of Historic Sites and Districts, Prince George's County, Maryland". www.mncppcapps.org. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Atlas of 15 mi around Washington including the County of Prince George Maryland. GM Hopkins C.E., 32 Walnut Street, Philadelphia 1878, reprinted by the Prince George's County historical society, Riverdale, Maryland 20840, 1975

- ↑ Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms (August 29, 2017). "College Park Airport (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Community Summary Sheet, Prince George's County" (PDF). College Park, Maryland. Maryland State Highway Administration, 1999. May 10, 2008.

- 1 2 Lakeland Community Heritage Project (2009). Lakeland: African Americans in College Park. Arcadia. ISBN 978-0738567594.

- ↑ Suehsdorf, A. D. (1978). The Great American Baseball Scrapbook, p. 103. Random House. ISBN 0-394-50253-1.

- ↑ Bernard, Diane (November 2, 2021). "A university town explores reparations for a Black community uprooted by urban renewal". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- 1 2 Maake, Katishi (October 31, 2018). "Wallace Loh helped change the relationship between UMd. and College Park. There's hope that work will continue after he's gone". Bisnow. Bisnow Media. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ↑ Shaver, Katherine (January 1, 2018). "University of Maryland is bringing upscale hotels, restaurants to College Park". Washington Post.

- ↑ "University of Maryland's Discovery District is latest effort to revitalize College Park". The Diamondback. February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Discovery District". Greater College Park. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2022/11/03/innovative-college-park-development.html

- ↑ "Getting 'Greater' in Fall 2021". Maryland Today. September 14, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "The Latest on Greater College Park". Maryland Today. November 3, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Lazo, Luz (May 20, 2020). "3 years of roadwork to begin on stretch of Route 1 in College Park". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Umaña, José (May 2, 2019). "New Computer Science building unveiled on Maryland Day". thesentinel.com. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Umaña, José (November 6, 2019). "University of Maryland breaks ground on new Public Policy school building". thesentinel.com. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Althouse, Michaela (May 10, 2022). "UMD is officially opening its IDEA Factory building for entrepreneurship". Technical.ly. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ "Black Lives Matter". City of College Park, Maryland. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ↑ Planas, Antonio (March 2, 2023). "Maryland mayor arrested on 56 counts of child pornography and resigns from post, officials say". NBC News. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ "Former College Park mayor receives 30-year sentence in child porn case". Fox 5 DC. November 21, 2023. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/11/08/fbi-headquarters-chosen-greenbelt/

- ↑ "Greenbelt, Maryland chosen as location for new FBI Headquarters". wusa9.com. November 8, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ "College Park, Maryland Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ↑ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Maryland 1996 Tornadoes". www.weather.gov. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "College Park Climate, Weather by month". Weather Spark. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "College Park, MD Factsheet". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Bednar, Adam (February 3, 2017). "University of Maryland announces 'Discovery District'". Maryland Daily Record. Archived from the original on December 24, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Spivack, Miranda S. (November 20, 2018). "Universities Look to Strengthen the Places They Call Home". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Eckstein, Megan (April 12, 2021). "Navy Software Factory, The Forge, Wants to Reshape How Ships Get Upgraded". US Naval Institute News.

- ↑ "IonQ (IONQ) - Market capitalization". companiesmarketcap.com. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Quantum at Maryland". Quantum at Maryland. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Lowering The Barrier Of Entry For Quantum Technology | Quantum Catalyzer". Q_Cat MAIN site. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "IonQ and University of Maryland Establish…". UMD Right Now. September 8, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Daughters, Gary. "Maryland: Maryland Leaps Ahead with Quantum: State support and legacy institutions spark a vibrant crop of startups and corporate partnerships". Site Selection. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Community". University of Maryland. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Kelly, Emilly (December 18, 2023). "NFL's Commanders To Shift Headquarters to University of Maryland's Discovery District". CoStar.

- 1 2 "Annual Comprehensive Financial Report 2022". City of College Park. January 6, 2023.

- ↑ https://www.collegeparkmd.gov/collegeparkday/

- ↑ "City of College Park Parade | City of College Park, Maryland". www.collegeparkmd.gov. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Friday Night LIVE! | City of College Park, Maryland". collegeparkmd.gov. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Winter Wonderland | City of College Park, Maryland". www.collegeparkmd.gov. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Farmers Markets". City of College Park, Maryland. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Farmers Market". UMD Dining Services. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Nyumburu Amphitheater". Adele H. Stamp Student Union. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ↑ Maring, Eric (October 30, 2020). "The Old Parish House: College Park's music temple". Streetcar Suburbs News. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ↑ "The Hall CP and Clarice hold inaugural Jazz Fest". The Diamondback. April 18, 2023. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Lemon Zest Festival brings together local musicians, artists". The Diamondback. September 25, 2023. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Calvert Hills Historic District". Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- ↑ "National Championships". Umterps.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "University of Maryland National Championships". umterps.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ Maryland colleges get high and low marks on Princeton Review study Archived May 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Baltimore Business Journal, August 1, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Best Colleges Press Release". Princetonreview.com. August 1, 2011. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Parks & Playgrounds". City of College Park, Maryland. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Lake Artemesia Natural Area". Birders Guide to Maryland and DC. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ Phillips, Colin (November 13, 2020). "College Park's trails are a regional activity hub". Streetcar Suburbs News. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Hollywood Gateway Park is officially open, after more than a year delay". The Diamondback. October 9, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Paint Branch Community Park Disc Golf". MNCPPC. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "parkrun is one of my favorite things about College Park". parkrun. November 1, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ↑ Jayaraman, Sahana (October 7, 2019). ""It's like a family": How College Park's weekly 5K has brought the community together". The Diamondback. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ↑ Phillips, Colin (December 29, 2023). "2023 in Review (Report 316)". College Park parkrun.

- ↑ "COLLEGE PARK WAR VETERANS MEMORIAL". National War Memorial Registry. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Ellen E. Linson Splash Park". MNCPPC. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Herbert Wells Ice Rink". MNCPPC. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "College Park Mayors". Maryland Manual On-Line. Maryland State Archives. December 7, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Office of the City Manager". City of College Park, Maryland. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ "District 1 Station – Hyattsville Archived September 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Prince George's County Police Department. Retrieved on September 9, 2018. Beat map Archived September 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "COLLEGE PARK." U.S. Postal Service. Retrieved on September 11, 2018. "4815 CALVERT RD COLLEGE PARK, MD 20740-9997"

- ↑ "NORTH COLLEGE PARK." U.S. Postal Service. Retrieved on September 11, 2018. "9591 BALTIMORE AVE COLLEGE PARK, MD 20740-9996"

- ↑ "About College Park VFD". College Park Volunteer Fire Department Co. 12. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- ↑ Maryland State Board of Elections. "Voter Registration Introduction".

- ↑ "Michael Mann". Sidley Austin LLP. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ↑ "Student Government Association (SGA)". Archived from the original on February 8, 1999. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ Holt, Brady (November 4, 2009). "Both incumbents tossed out in District 4". Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Marcus D. Afzali (I)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ↑ Shaver, Katherine (January 26, 2022). "Md. board approves $3.4 billion contract to complete Purple Line". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Shaver, Katherine (December 19, 2019). "Purple Line will open first between College Park and New Carrollton, state says". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019.

- ↑ www.wmucradio.com.

- ↑ Harris, Susan (May 29, 2020). "Welcome to New College Park Newspaper!". Greenbelt Online. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ↑ "District_BIG_WALL_MAP_2009d_36x48_July_2013.pdf Archived 2016-12-22 at the Wayback Machine." City of College Park. Retrieved on January 31, 2018. See also: City's listing of area schools Archived January 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, neighborhood map Archived January 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "NEIGHBORHOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS AND BOUNDARIES SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018." Prince George's County Public Schools. Retrieved on January 31, 2018.

- ↑ "NEIGHBORHOOD MIDDLE SCHOOLS AND BOUNDARIES SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018." Prince George's County Public Schools. Retrieved on January 31, 2018.

- ↑ "NEIGHBORHOOD HIGH SCHOOLS AND BOUNDARIES SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018." Prince George's County Public Schools. Retrieved on January 31, 2018.

- 1 2 "Local Schools Archived 2018-01-31 at the Wayback Machine." Prince George's County Public Schools. Retrieved on January 31, 2018.

- ↑ Weaver, Rosanna Landis (January 15, 2013). "Charter school to open in Hyattsville". Hyattsville Life & Times. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Contact Us Archived 2018-09-06 at the Wayback Machine." College Park Academy Public Charter School. Retrieved on September 6, 2018. "5751 Rivertech Court Riverdale Park, MD 20737"

- ↑ Meyer, Eugene K. (September 28, 2000). "Douglass High: A School of Their Own". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ↑ Lakeland Community Heritage Project Inc. Lakeland: African Americans in College Park. Arcadia Publishing, September 18, 2012. ISBN 1439622744, 9781439622742. Google Books PT32.

- ↑ Lakeland Community Heritage Project Inc. Lakeland: African Americans in College Park. Arcadia Publishing, September 18, 2012. ISBN 1439622744, 9781439622742. Google Books PT31-PT32.

- 1 2 "Fairmont Heights High School History". Fairmont Heights High School. September 4, 2018. Archived from the original on October 4, 2005. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ↑ African-American Historic and Cultural Resources in Prince Georges County, Maryland . The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, February 2012. p. 66 (PDF p. 15/152). Also available on Issuu, on document page 70.

- ↑ "Contact Us Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine." Al Huda School. Retrieved on February 1, 2018. "5301 Edgewood Road, College Park, MD 20740"

- ↑ "About Al-Huda School Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine." Al Huda School. Retrieved on February 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Contact Us." Saint Francis International School. Retrieved on January 31, 2018. "St. Mark Campus 7501 Adelphi Road Hyattsville, MD 20783"

- ↑ "St. Mark's School in Hyattsville holds reunion to marks its 50th year Archived 2018-09-06 at the Wayback Machine." Catholic Standard, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington. Wednesday, October 15, 2008. Retrieved on January 31, 2018. "St. Mark Campus 7501 Adelphi Road Hyattsville, MD 20783"

- ↑ Roberts, Tom. "Maryland Catholic school finds its footing amid demographic shifts." Catholic Standard, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington. Wednesday, October 15, 2008. Retrieved on February 1, 2018.

Further reading

- "Langley Park-College Park-Greenbelt Approved Master Plan (October 1989) and Adopted Sectional Map Amendment." Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, May 1990. Read online.

- "The Approved College Park-Riverdale Park Transit District Development Plan." Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, March 2015. Read online.

- A Guide to the City of College Park, from the College Park City Hall.

- Niel, Clara (September 21, 2020). "For those raised in College Park's Lakeland, the wounds left by its destruction remain". The Diamondback. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- A History of the Lakeland Community of College Park (video presentation). Corridor Conversations, February 2022.

External links

- Official website

Geographic data related to College Park, Maryland at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to College Park, Maryland at OpenStreetMap- Route 1 Communities: College Park