Streetcars and interurbans operated in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., between 1890 and 1962.

Lines in Maryland were established as separate legal entities, most with grand plans in mind, but none succeeded financially. Eventually they were all owned or leased by DC Transit (see Streetcars in Washington, D.C.). Unlike the Virginia lines, the combined Washington and Maryland lines were scheduled as a single system. A combination of the rise of the automobile, various economic downturns and bustitution eventually spelled the end of streetcars in southern Maryland.

Companies

Rock Creek Railway

One of the first electric streetcar companies in Washington, D.C., the Rock Creek Railway was incorporated in 1888 and started operations in 1890. After expansion, the line ran from the Cardoza/Shaw neighborhood of D.C. to Chevy Chase Lake, Maryland. On September 21, 1895, the company purchased the Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company and the two formed the Capital Traction Company.

Remnants of the Line include:

- The Chevy Chase Lake waiting station that existed at the northern end of the line was disassembled in 1980 and moved to Hyattstown, Maryland.[1]

Tennallytown and Rockville Railroad

A trio of streetcar companies provided service from Georgetown north and ultimately to Rockville, Maryland. The first one was the Georgetown and Tennallytown Railway, chartered on August 22, 1888, and just the third D.C. streetcar company to incorporate.[2] It began operations in 1890 on a route that ran up from M Street NW up 32nd Street NW[3] and then onto the Georgetown and Rockville Road (now Wisconsin Avenue NW) to the extant village of Tenleytown. That same year,[4] the Tennallytown and Rockville Railway received its charter and began building tracks from the G&T's northern terminus to today's D.C. neighborhood of Friendship Heights and the Maryland state line.[5] Finally, the Washington and Rockville Electric Railway was incorporated in 1897[4] to extend the tracks into Maryland line and onward to Bethesda and Rockville.[6] Controlling interest in the companies was obtained first by the Washington Traction and Electric Company, then in 1902 by the Washington Railway and Electric Company. Streetcar service was replaced with buses in 1935.

Stations of the T&R and W&R included:

- Tennallytown (Tenleytown)

- Somerset

- Bethesda

- Alta Vista

- Bethesda Park

- Montrose

- Halpine

- Fairgrounds

- Rockville

Remnants of the line include:

- Wisconsin Avenue and Old Georgetown Road still exist

- The Bethesda Trolley Trail, a rail trail that runs along the old right-of-way

- Woodglen Drive in Rockville

Glen Echo Railroad

Opened on June 10, 1891, the Glen Echo Railroad initially ran about 2.5 miles from Wisconsin Avenue due west to Conduit Road (today's Macarthur Boulevard). The line connected Tennallytown and Rockville Railroad's terminal at Willard Avenue near Friendship Heights to a masonry car barn and powerhouse near the intersection of Walhonding Road.

In 1895, a proposed sale of the railroad, desired by its creditors, was stopped by injunction of its owners.[7] In 1896, the company renamed itself the Washington and Glen Echo Railroad and extended its line from its western terminus northwest through Glen Echo proper to Cabin John. Shortly thereafter, the railroad began to extend its line east of Wisconsin Avenue, thanks to the Chevy Chase Land Company, which granted the railroad permission to cross its land and extend the line about two-thirds of a mile northeastward to Chevy Chase Circle,[8] where it connected with the Capital Traction Company's Rock Creek Railway line. After the connection to the Circle was made, a new, more direct line would be laid from the circle through the town of Somerset to the Conduit-Walhonding car barn, resulting in a new crossing of the Tennallytown and Rockville line about a quarter-mile north of the Wisconsin-Willard terminal.[9] This new alignment may have been planned to benefit the line's owners, "Philadelphia capitalists" who "own considerable real estate at Somerset Heights".[10]

The railroad was abandoned in 1902, but the section from Walhonding Road to Cabin John was incorporated into the Washington and Great Falls Electric Railway.[11]

The car barn was not totally demolished until after 1940.[11] Railroad tracks and the trestle site remain visible in the Willard Avenue Neighborhood Park in Bethesda, Maryland.[12]

Washington and Great Falls Electric Railway

Incorporated in 1892 and opened in 1895, the Washington and Great Falls Electric Railway Company (WGFERC) began in Georgetown at the Georgetown Car Barn on 36th and Prospect Streets and ran in a private right-of-way along the lands of the Washington Aqueduct to Glen Echo and from there along the old tracks of the Glen Echo Railroad to Cabin John. Because the railroad never reached Great Falls, but instead terminated at Cabin John, it was often referred to as the "Cabin John Trolley". In 1902 the WGFERC purchased the bankrupt Washington Traction and Electric Company (a holding company for 10 streetcar lines). The merged company was renamed as the Washington Railway & Electric Company (WREC).[13]: 10 In 1933 WREC was acquired by the Capital Traction Company. The railway line to Cabin John was abandoned in 1960.[13]: 12 The former roadbed is still discernible in The Palisades and in Montgomery County, Maryland.[14]

Remnants of the line in Montgomery County include:

- Trestle over Walhonding Brook, between MacArthur Boulevard and Clara Barton Parkway

- Trestle over Minnehaha Branch on northwest side of Glen Echo Park. After a 2006 land swap that gave this section of the right-of-way to the National Park Service, this trestle was rehabilitated in 2014 and the MacArthur Boulevard Bike Path was rerouted to pass over it.[15][16]

- Trestle over Braeburn Branch just west of Wellsley Circle

- Much of the right-of-way from Brookmont to Cabin John Parkway is extant.

City and Suburban Railway

The City and Suburban Railway was chartered in 1890 to run a streetcar from just east of the White House at New York Avenue and 15th Street NW to what is now Mount Rainier, Maryland, just over the D.C. border.

The line reached Mount Rainier in 1897. In 1898, it merged with the Eckington and Soldiers' Home Railway and continued building tracks, reaching Brentwood in 1898 and Hyattsville and Riverdale in 1899. The company was also building a line south from Baltimore, making it as far as Ellicott City. The two lines never connected and the Baltimore line became Trolley Line Number 9.

Meanwhile, on March 31, 1892, the Maryland and Washington Railway incorporated to build a rail line connecting any passenger railway in the District of Columbia to Branchville and eventually Laurel. The company had difficulty raising money, and on April 4, 1896, merged with several other struggling streetcar companies to create the Columbia and Maryland Railway, which presently renamed itself the Berwyn and Laurel Electric Railroad Company. It began building tracks from the end of the City and Suburban line in Riverdale to College Park, reaching Laurel by 1902, when it changed its name again, this time to the Washington, Berwyn and Laurel Electric Railroad Company.

Eventually, the City and Suburban took control of the Washington, Berwyn and Laurel until it was itself absorbed by the Washington Railway and Electric Company.

The City and Suburban had stops in the following cities.

- Hyattsville

- Riverdale

- College Park

- Lakeland

- Berwyn

- Branchville

- Beltsville

- Contee

- Laurel

Remnants of the line include:

- Stations

- 4701 Queensbury Road, Riverdale Park

- 531 Main Street, Laurel, now Oliver's Old Towne Tavern[17]

- Roads

- Bus Turnaround north of the intersection of Rhode Island Avenue and 34th Street in Mount Rainier used to be a streetcar turnaround

- Rail Trails

Washington, Woodside and Forest Glen Railway Power Company

The Washington, Woodside and Forest Glen Railway, aka the "Forest Glen Trolley", was incorporated on July 26, 1895, and built a 2.9-mile line that opened on November 25, 1897. A single ride cost five cents. The streetcar ran from the terminus of the Brightwood Railway at Eastern Avenue and Georgia Avenue along the west side of Georgia Avenue and then along what is now Seminary Road to the National Park Seminary, a fashionable school for girls in Forest Glen, at Forest Glen Road. This line faced competition from passenger service on the Metropolitan Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The line was shut down on December 15, 1924, in preparation for construction of the first Georgia Avenue underpass under the B&O Railroad. The underpass was built with one lane for the trolley tracks, but the trolley never resumed operation.

Stations on the line were:

- Silver Spring

- Sligo

- Woodside

- Forest Glen

The Kensington Railway

Incorporated in 1894, the Chevy Chase Lake & Kensington Railway began operation on May 30, 1895, along a single-track line beginning at the northern terminus of the old Rock Creek Railway at Chevy Chase Lake along Connecticut Avenue and running north to a station on University Boulevard in Kensington. Purchased at foreclosure and renamed the Kensington Railway, the line was extended several times, and in 1916 reached its fullest extent to a station a mile and a half north. From 1923 to 1933, the line was leased by Capital Traction. Returned to independent operations, the railroad ran its last car on September 15, 1935, the last car ran its route. When the line south of the Kensington was replaced with buses, the railway no longer had access to power and operations were suspended. It never reopened.[18]

The right-of-way was eventually converted into Kensington Parkway. Its trestle over Rock Creek was dismantled, but its stone abutments survive, just east of the parkway.

The Baltimore and Washington Transit Company

The B&W Transit Company was incorporated on April 7, 1896. In 1897, it began construction on an electric street railway system, known locally as the Dinky Line, that began at 4th and Butternut Streets NW (then known as Umatilla St), traveled south on 4th to Aspen Street NW (then known as Tahoe Street) and then east on Aspen and Laurel Streets NW (then known as Spring Street) into Maryland. It continued on Ethan Allen Avenue until it reached the hugely popular Wildwood Resort and Glen Sligo Hotel on Sligo Creek, which would be about midway between Elm Avenue and Sligo Creek Parkway, on what is Heather Avenue today. In 1903, the Takoma Park city council took over the lease given by the B & W Transit Company and the resort was closed for illegal gambling. The tracks were removed some two years later and the right-of-way reverted to the town. In 1920, the hotel was torn down and the property subdivided into individual lots. In 1937, the tracks were completely dismantled.

The Washington, Spa Spring and Gretta Railroad Company

Began in 1910 as a single-track trolley line. It ran from a car barn at 15th and H Street NE in Washington along Bladensburg Road to Bladensburg. The line was initially planned to run as far as Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, but service was only extended as far as Berwyn Heights. (This happened in 1912 using battery cars.) The line became the Washington Interurban Railway in 1912 and the Washington Interurban Railroad Company in 1916. In 1923 the streetcars were replaced by buses and the tracks removed when Bladensburg Road was paved.

Washington and Great Falls Railway and Power Company

From 1913 to 1921, the Washington and Great Falls Railway and Power Company operated a 10.66-mile line to Great Falls from Bethesda—specifically, from a junction with the Washington and Rockville Railway at Wisconsin Avenue and Bradley Lane.[19] The only streetcar line ever to actually reach Great Falls, it was a project of developers looking to attract customers to their land west of Wisconsin Avenue.

The developers incorporated the WGFRPC on May 29, 1912,[19] and on December 4, received permission from Maryland's Public Service Commission to hire the Chevy Chase to Great Falls Land Corporation to build the rail line.[20] The right-of-way became Bradley Boulevard from Wisconsin to River Road, then followed its own route to its western terminus.

Sometime between 1912 and 1914, the WGFRPC built a transformer station in the form of a stone farmhouse to boost power to the trolleys running the route. The structure was later converted into a residence; it still stands at 8100 Bradley Boulevard, a road created largely by paving over the former trolley right-of-way.[21]

The line opened on July 2, 1913.[22] The developers were uninterested in operating a streetcar as a business, and so paid the Washington Railway & Electric Company—specifically, its Washington and Rockville Railway subsidiary—to furnish, operate, and power the rolling stock.[19][23]

It was generally operated as a stub, and often with just a single trolley shuttling back and forth. "However, for at least a while, a through service was operated to downtown Washington, with cars from Great Falls running all the way to 8th Street," the National Capital Trolley Museum wrote in 2012.[23] Some passengers rode to the Great Falls Tavern; also known as the Great Falls Hotel[24].[21] The railroad ceased operations on February 12, 1921,[22] and the tracks were removed in 1926.

Remnants of the line include the Gold Mine Spur Trail in Chesapeake and Ohio National Historical Park, which uses about 1,000 feet of the Washington and Great Falls rail bed and cut.

Interurbans

Trolley parks

See also

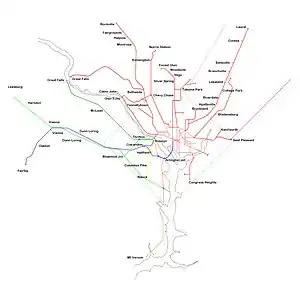

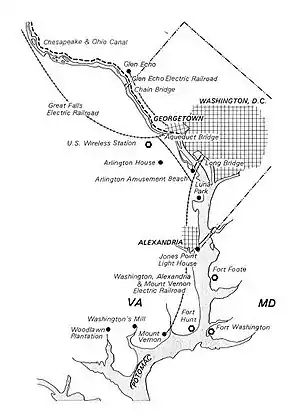

- 1880 map of D.C. streetcar lines[25]

- Washington Metro

- Urban rail transit

- Bustitution

- Trolley park

- National Capital Trolley Museum

- Map of Montgomery Country streetcar lines

References

- ↑ Cranor, David. "The Chevy Chase Trolley station that moved to the country". Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ Office of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia (1896). Laws Relating to Street-railway Franchises in the District of Columbia. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 2023-07-16. Retrieved 2023-08-22 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Commission, United States Interstate Commerce (1912). Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Reports and Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. L.K. Strouse. Archived from the original on 2023-07-16. Retrieved 2023-10-30.

- 1 2 E.H.T. Traceries, Inc (June 2005). "Streetcar and Bus Resources of Washington, D.C., 1862-1962 / NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior / National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-21. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ "Washington Neighborhoods". The United States National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- ↑ Kimberly Protho Williams (2001). "Cleveland Park Historic District" (PDF). The Cleveland Park Historic District. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Stopped by Injunction". The Baltimore Sun. 1895-08-10. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ↑ "Chevy Chase Circle tracks". Evening star. 1896-05-09. p. 13. Archived from the original on 2023-08-31. Retrieved 2023-08-31.

- ↑ "Chevy Chase Circle tracks". Evening star. 1896-05-09. p. 13. Archived from the original on 2023-08-31. Retrieved 2023-08-31.

- ↑ "Railroad Stock Changes Hands". Baltimore Sun. 17 Sep 1898. Archived from the original on 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- 1 2 E.H.T. Traceries, Inc (June 2005). "Streetcar and Bus Resources of Washington, D.C., 1862-1962 / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior / National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-21. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ "Willard Avenue Neighborhood Park". MontgomeryParks.org. Silver Spring, Maryland: Montgomery County Department of Parks. Archived from the original on 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - 1 2 "History of the Washington & Great Falls Electric Railway". Palisades Trolley Trail; Historic Resource Report; Appendix 4 (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: District of Columbia Department of Transportation. December 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ↑ "Street Cars, Sears Houses, And The Palisades". LostLandmarks.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ↑ Cranor, David (2014-07-23). "Work underway on the Minnehaha Creek trolley bridge". WashCycle. Archived from the original on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ "Property Exchange with National Park Service" (PDF). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. 2006-01-05. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2008.

- ↑ "Oliver's Olde Town Tavern". Laurel, Maryland. Archived from the original on 2005-12-18. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ↑ Tuttle, Frederick B. (15 September 1935). "Picturesque Green Trams Become Ghosts after 40 years". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 3 Moody's Manual of Railroads and Corporation Securities. Moody Manual Company. 1920.

- ↑ Report of the Public Service Commission of Maryland for the Year 1912. Baltimore: Public Service Commission of Maryland. 1913.

- 1 2 Rothrock, Gail (February 1979). "INVENTORY FORM FOR STATE HISTORIC SITES SURVEY: Electric Trolley Substation / Washington & Great Falls Railway & Power Company" (PDF). MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- 1 2 KCI Technologies, Inc (October 1999). "Community Summary Sheet" (PDF). MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION / STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- 1 2 "Trolley Trail of the Week #3: Gold Mine Trail, Great Falls, MD unit of C&O Canal National Historic Park--Washington & Great Falls Railway & Power Co". National Capital Trolley Museum. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ↑ "Local History: The "Mother Stewart" Mystery – Community of Cabin John, Maryland". Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ↑ EHT Traceries (December 2019). "Palisades Trolley Trail | Historic Resource Report" (PDF). District Department of Transportation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2022-07-29.