| Battle of Stalingrad | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||||

Clockwise from top left: (1) Soviet 76.2 mm ZiS-3 field gun, in firing position. (2) Red Army soldiers on roof of house. (3) German Ju 87 after a dive bomber attack. (4) Axis POWs (Germans, Italians, Romanians, Hungarians) (5) Soviet troops fighting in a destroyed workshop. (6) German Sturmgeschütz III on the move. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

Initial:

At the time of the Soviet counter-offensive: |

Initial:

At the time of the Soviet counter-offensive: | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

See casualties section. | ||||||||

| Total dead: 1,000,000–1,900,000[17][18][19] | |||||||||

The Battle of Stalingrad[Note 7] (23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943)[20][21][22] was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later renamed Volgograd) in Southern Russia. The battle was marked by fierce close-quarters combat and direct assaults on civilians in air raids, with the battle epitomizing urban warfare.[23][24][25] It was the bloodiest battle of the Second World War, with both sides suffering enormous casualties.[26][27][28] Today, the Battle of Stalingrad is often regarded as the turning point in the European theatre of war,[29] as it forced the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (German High Command) to withdraw considerable military forces from other areas in occupied Europe to replace German losses on the Eastern Front, ending with the rout of the six field armies of Army Group B, including the destruction of Nazi Germany's 6th Army and an entire corps of its 4th Panzer Army.[30] The Soviet victory energized the Red Army and shifted the balance of power in the favour of the Soviets.

Stalingrad was strategically important to both sides as a major industrial and transport hub on the Volga River. Whoever controlled Stalingrad would have access to the oil fields of the Caucasus and would gain control of the Volga.[31] Germany, already operating on dwindling fuel supplies, focused its efforts on moving deeper into Soviet territory and taking the oil fields at any cost. On 4 August, the Germans launched an offensive by using the 6th Army and elements of the 4th Panzer Army. The attack was supported by intense Luftwaffe bombing that reduced much of the city to rubble. The battle degenerated into house-to-house fighting as both sides poured reinforcements into the city. By mid-November, the Germans, at great cost, had pushed the Soviet defenders back into narrow zones along the west bank of the river. Winter conditions became particularly brutal,[24] with temperatures reaching as low as −40 °C (−40 °F) in late November.[32]

On 19 November, the Red Army launched Operation Uranus, a two-pronged attack targeting the Romanian armies protecting the 6th Army's flanks.[33] The Axis flanks were overrun and the 6th Army was cut off and surrounded in the Stalingrad area. Adolf Hitler was determined to hold the city at all costs and forbade the 6th Army from trying a breakout; instead, attempts were made to supply it by air and to break the encirclement from the outside. The Soviets were successful in preventing the Germans from delivering enough supplies through the air to the trapped Axis forces. Nevertheless, heavy fighting continued for another two months. On 2 February 1943, the German 6th Army, having exhausted their ammunition and food, finally capitulated after over five months of fighting, making it the first of Hitler's field armies to surrender in World War II.[34]

The Soviet victory is commemorated in Russia as the Day of Military Honour.

Background

By the spring of 1942, despite the failure of Operation Barbarossa to vanquish the Soviet Union in a single campaign, the Wehrmacht had captured vast expanses of territory, including Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic republics. On the Western Front, Germany held most of Europe, the U-boat offensive in the Atlantic was holding American support at bay, and in North Africa Erwin Rommel had just captured Tobruk.[35]: 522 In the east, the Germans had stabilised a front running from Leningrad south to Rostov, with a number of minor salients. Hitler was confident that he could break the Red Army despite the heavy German losses west of Moscow in winter 1941–42, because Army Group Centre (Heeresgruppe Mitte) had been unable to engage 65% of its infantry, which had meanwhile been rested and re-equipped. Neither Army Group North nor Army Group South had been particularly hard-pressed over the winter.[36]

Hitler decided that Germany's summer campaign in 1942 would be directed at the southern parts of the Soviet Union. The initial objectives in the region around Stalingrad were to destroy the industrial capacity of the city and to block the Volga River traffic connecting the Caucasus and Caspian Sea to central Russia, as the city is strategically located near a big bend of the Volga. The Germans cut the pipeline from the oilfields when they captured Rostov on 23 July. The capture of Stalingrad would make the delivery of Lend-Lease supplies via the Persian Corridor much more difficult.[37][38][39]

On 23 July 1942, Hitler personally rewrote the operational objectives for the 1942 campaign, greatly expanding them to include the occupation of the city of Stalingrad. Both sides began to attach propaganda value to the city, which bore the name of the Soviet leader meaning that the capture of the city would have been a great ideological victory for the Reich.[40] Hitler proclaimed that after Stalingrad's capture, its male citizens were to be killed and all women and children were to be deported because its population was "thoroughly communistic" and "especially dangerous".[41] Hitler planned for the fall of the city firmly securing the northern and western flanks of the German armies as they advanced on Baku, with the aim of gaining its strategic petroleum resources for Germany.[35]: 528 The expansion of objectives was a significant factor in Germany's failure at Stalingrad, caused by German overconfidence and an underestimation of Soviet reserves.[42]

Meanwhile, Stalin was convinced by Soviet intelligence that the main German attack would target Moscow,[43] and gave priority for fresh troops and the new equipment to the defense of the Soviet capital. As the Soviet winter counteroffensive of 1941–1942 culminated in March, the Soviet high command began planning for the summer campaign. Stalin desired a general offensive, but was dissuaded by Chief of the General Staff Boris Shaposhnikov, Deputy Chief of the General Staff Aleksandr Vasilevsky, and Western Main Direction commander Georgy Zhukov. Ultimately, Stalin instructed that the summer campaign be based on what he termed "active strategic defense," but also ordered the Soviet high command, Stavka, to began planning for a series of local offensives across the Eastern Front.[44]

Southwestern Main Direction commander Semyon Timoshenko suggested an attack from the Izyum salient south of Kharkov in northeastern Ukraine, gained during the winter campaign, to take advantage of what Soviet intelligence believed to be weak opposing forces in that sector and divert German troops from the anticipated attack on Moscow. His proposal for a drive on Kharkov by the Southwestern Front, advancing in a northern and southern pincer to encircle and destroy the German 6th Army received Stalin's approval despite the opposition of Shaposhnikov and Vaslievsky.[45]

After delays in moving troops into position and logistical difficulties, the Kharkov operation began on 12 May. The Soviet troops achieved initial success and 6th Army commander Friedrich Paulus requested reinforcements. Three divisions slated for Case Blue and air units from Crimea were diverted to the Kharkov sector. The advance of Southwestern Front's northern strike group was halted by a German counterattack that began on 13 May, while the front's southern strike group continued its progress 40 kilometers into the German rear.[46] In response, Ewald von Kleist's two armies launched a counterattack, Operation Fridericus I, on 17 May against the Southern Front, covering the Southwestern Front's southern flank. Kleist's counterattack caught the Soviet defenders off guard, with Timoshenko having committed his armored reserves to the Kharkov operation. In the ensuing Second Battle of Kharkov, Kleist's forces encircled and destroyed much of the forces of the Southern Front and the advancing Southwestern Front, inflicting over 300,000 casualties in return for losses of 20,000. The disaster at Kharkov was a crippling blow to the Soviet forces in the south, leaving them vulnerable to the forthcoming German summer offensive. Despite the defeat, Stalin continued to believe that a German attack on Moscow was the main threat and allocated four newly formed strategic reserve armies there rather than to the Southwestern Main Direction. Instead, the Southwestern Front received seven rifle divisions and three tank corps, which proved inadequate to deal with the German threat.[47]

At the same time, the commitment of the panzer divisions that Paulus and Kleist needed for Case Blau to the Second Battle of Kharkov further delayed the start of the offensive, since they required time to train and replace their losses from the battle. At a conference at Army Group South's headquarters at Poltava on 1 June, Hitler modified the plans for the summer operations. Before the main offensive began, simultaneous attacks were to be launched on 7 June: Operation Wilhelm at Volchansk northeast of Kharkov and Operation Störfang against Sevastopol. The latter aimed to destroy the last Soviet troops in Crimea in order to secure the German southern flank. Kleist was to follow with these Operation Fridericus II on 12 June against the Izyum salient. The attacks in Ukraine aimed to give German forces space to amass supplies east of the Donets. The start of Case Blau itself was delayed to 20 June, by which point victory in the preliminary operations was anticipated.[48]

Prelude

If I do not get the oil of Maikop and Grozny then I must finish [liquidieren; "kill off", "liquidate"] this war.

.jpg.webp)

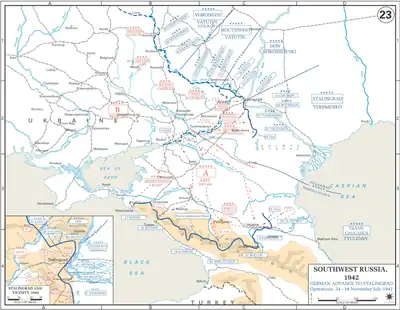

Army Group South was selected for a sprint forward through the southern Russian steppes into the Caucasus to capture the vital Soviet oil fields there. The planned summer offensive, code-named Fall Blau (Case Blue), was to include the German 6th, 17th, 4th Panzer and 1st Panzer Armies. Army Group South had overrun the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1941. Poised in Eastern Ukraine, it was to spearhead the offensive.[49]

Hitler intervened, however, ordering the Army Group to split in two. Army Group South (A), under the command of Wilhelm List, was to continue advancing south towards the Caucasus as planned with the 17th Army and First Panzer Army. Army Group South (B), including Paulus's 6th Army and Hermann Hoth's 4th Panzer Army, was to move east towards the Volga and Stalingrad. Army Group B was commanded by General Maximilian von Weichs.[50]

The start of Case Blue had been planned for late May 1942. However, a number of German and Romanian units that were to take part in Blau were besieging Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula. Delays in ending the siege pushed back the start date for Blau several times, and the city did not fall until early July.

Operation Fridericus I by the Germans against the "Izyum bulge", pinched off the Soviet salient in the Second Battle of Kharkov, and resulted in the envelopment of a large Soviet force between 17 May and 29 May. Similarly, Operation Wilhelm attacked Voltshansk on 13 June, and Operation Fridericus attacked Kupiansk on 22 June.[51]

Blau finally opened as Army Group South began its attack into southern Russia on 28 June 1942. The German offensive started well. Soviet forces offered little resistance in the vast empty steppes and started streaming eastward. Several attempts to re-establish a defensive line failed when German units outflanked them. Two major pockets were formed and destroyed: the first, northeast of Kharkov, on 2 July, and a second, around Millerovo, Rostov Oblast, a week later. Meanwhile, the Hungarian 2nd Army and the German 4th Panzer Army had launched an assault on Voronezh, capturing the city on 5 July.

The initial advance of the 6th Army was so successful that Hitler intervened and ordered the 4th Panzer Army to join Army Group South (A) to the south. A massive road block resulted when the 4th Panzer and the 1st Panzer choked the roads, stopping both in their tracks while they cleared the mess of thousands of vehicles. The traffic jam is thought to have delayed the advance by at least one week. With the advance now slowed, Hitler changed his mind and reassigned the 4th Panzer Army back to the attack on Stalingrad.

By the end of July, the Germans had pushed the Soviets across the Don River. At this point, the Don and Volga Rivers are only 65 km (40 mi) apart, and the Germans left their main supply depots west of the Don, which had important implications later in the course of the battle. The Germans began using the armies of their Italian, Hungarian and Romanian allies to guard their left (northern) flank. Occasionally Italian actions were mentioned in official German communiques.[52][53][54][55] Italian forces were generally held in little regard by the Germans, and were accused of low morale: in reality, the Italian divisions fought comparatively well, with the 3rd Infantry Division "Ravenna" and 5th Infantry Division "Cosseria" showing spirit, according to a German liaison officer.[56] The Italians were forced to retreat only after a massive armoured attack in which German reinforcements failed to arrive in time, according to German historian Rolf-Dieter Müller.[57]

On 25 July the Germans faced stiff resistance with a Soviet bridgehead west of Kalach. "We had had to pay a high cost in men and material ... left on the Kalach battlefield were numerous burnt-out or shot-up German tanks."[58]

The Germans formed bridgeheads across the Don on 20 August, with the 295th and 76th Infantry Divisions enabling the XIVth Panzer Corps "to thrust to the Volga north of Stalingrad." The German 6th Army was only a few dozen kilometres from Stalingrad. The 4th Panzer Army, ordered south on 13 July to block the Soviet retreat "weakened by the 17th Army and the 1st Panzer Army", had turned northwards to help take the city from the south.[59]

To the south, Army Group A was pushing far into the Caucasus, but their advance slowed as supply lines grew overextended. The two German army groups were too far apart to support one another.

After German intentions became clear in July 1942, Stalin appointed General Andrey Yeryomenko commander of the Southeastern Front on 1 August 1942. Yeryomenko and Commissar Nikita Khrushchev were tasked with planning the defence of Stalingrad.[60] Beyond the Volga River on the eastern boundary of Stalingrad, additional Soviet units were formed into the 62nd Army under Lieutenant General Vasiliy Chuikov on 11 September 1942. Tasked with holding the city at all costs,[61] Chuikov proclaimed, "We will defend the city or die in the attempt."[62] The battle earned him one of his two Hero of the Soviet Union awards.

Orders of battle

Red Army

During the defence of Stalingrad, the Red Army deployed five armies in and around the city (28th, 51st, 57th, 62nd and 64th Armies); and an additional nine armies in the encirclement counteroffensive[63] (24th, 65th, 66th Armies and 16th Air Army from the north as part of the Don Front offensive, and 1st Guards Army, 5th Tank, 21st Army, 2nd Air Army and 17th Air Army from the south as part of the Southwestern Front).

Axis

Attack on Stalingrad

Initial attack

David Glantz indicated[64] that four hard-fought battles – collectively known as the Kotluban Operations – north of Stalingrad, where the Soviets made their greatest stand, decided Germany's fate before the Nazis ever set foot in the city itself, and were a turning point in the war. Beginning in late August, continuing in September and into October, the Soviets committed between two and four armies in hastily coordinated and poorly controlled attacks against the Germans' northern flank. The actions resulted in more than 200,000 Soviet Army casualties but did slow the German assault.

On 23 August the 6th Army reached the outskirts of Stalingrad in pursuit of the 62nd and 64th Armies, which had fallen back into the city. Kleist later said after the war:

The capture of Stalingrad was subsidiary to the main aim. It was only of importance as a convenient place, in the bottleneck between Don and the Volga, where we could block an attack on our flank by Russian forces coming from the east. At the start, Stalingrad was no more than a name on the map to us.[65]

The Soviets had enough warning of the German advance to ship grain, cattle, and railway cars across the Volga out of harm's way, but Stalin refused to evacuate the 400,000 civilian residents of Stalingrad. This "harvest victory" left the city short of food even before the German attack began. Before the Heer reached the city itself, the Luftwaffe had cut off shipping on the Volga, vital for bringing supplies into the city. Between 25 and 31 July, 32 Soviet ships were sunk, with another nine crippled.[66]

The battle began with the heavy bombing of the city by Generaloberst Wolfram von Richthofen's Luftflotte 4. Some 1,000 tons of bombs were dropped in 48 hours, more than in London at the height of the Blitz.[67] At least 90% of the city's housing stock was obliterated.[68] The aerial assault on Stalingrad was the most concentrated on the Ostfront according to Beevor.[69] The exact number of civilians killed is unknown but was most likely very high. Around 40,000 civilians were taken to Germany as slave workers, some fled during battle and a small number were evacuated by the Soviets, but by February 1943 only 10,000 to 60,000 civilians were still alive. Much of the city was smashed to rubble, although some factories continued production while workers joined in the fighting. The Stalingrad Tractor Factory continued to turn out T-34 tanks up until German troops burst into the plant. The 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment was the only non-German unit[70] selected by the Wehrmacht to enter Stalingrad city during assault operations. It fought as part of the 100th Jäger Division.

Stalin rushed all available troops to the east bank of the Volga, some from as far away as Siberia. Regular river ferries were quickly destroyed by the Luftwaffe, which then targeted troop barges being towed slowly across by tugs.[60] It has been said that Stalin prevented civilians from leaving the city in the belief that their presence would encourage greater resistance from the city's defenders.[71] Civilians, including women and children, were put to work building trenchworks and protective fortifications. A massive German air raid on 23 August caused a firestorm, killing hundreds and turning Stalingrad into a vast landscape of rubble and burnt ruins. Ninety percent of the living space in the Voroshilovskiy area was destroyed. Between 23 and 26 August, Soviet reports indicate 955 people were killed and another 1,181 wounded as a result of the bombing.[72] Casualties were estimated to have been 40,000,[73][24] or as many as 70,000,[68] though these estimates were likely exaggerated,[74] and after 25 August the Soviets did not record any civilian and military casualties as a result of air raids.[Note 8]

The Soviet Air Force, the Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS), was swept aside by the Luftwaffe. The VVS bases in the immediate area lost 201 aircraft between 23 and 31 August, and despite meagre reinforcements of some 100 aircraft in August, it was left with just 192 serviceable aircraft, 57 of which were fighters.[75] The Soviets continued to pour aerial reinforcements into the Stalingrad area in late September, but continued to suffer appalling losses; the Luftwaffe had complete control of the skies.

Early on 23 August, the German 16th Panzer and 3rd Motorized Divisions attacked out of the Vertyachy bridgehead with a force 120 tanks and over 200 armored personnel carriers strong. The German attack broke through the 1382nd Rifle Regiment of the 87th Rifle Division and the 137th Tank Brigade, which were forced to retreat towards Dmitryevka. Encountering little resistance, the 16th Panzer Division drove east towards the Volga, supported by the strikes of Henschel Hs 129 ground attack aircraft.[76] Crossing the railway line to Stalingrad at 564 km Station around midday, both divisions continued their rush towards the river. Around 15:00, Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz's Panzer Detachment and the kampfgruppe of the 2nd Battalion, 64th Panzer Grenadier Regiment from the 16th Panzer reached the area of Latashanka, Rynok, and Spartanovka, northern suburbs of Stalingrad, and the Stalingrad Tractor Factory.[77]

One of the first units to offer resistance in this area was the 1077th Anti-Aircraft Regiment,[71] covering the Stalingrad Tractor Factory and the Volga ferry near Latashanka. The majority of the regiment was composed of men, but its directing and rangefinding crews and unit headquarters were made up of women. Several women also crewed anti-aircraft guns. The 1077th was notified of the German tanks' approach at 14:30 and its 6th Battery, dominating the Sukhaya Mechatka ravine, claimed the destruction of 28 German tanks. Later that day, its 3rd Battery on the road between Yerzovka and Stalingrad, saw particularly intense fighting against the 16th Panzer, reportedly fighting "shot for shot."[78] Two women were decorated for their actions that day, and the regiment's report praised the "exceptional steadfastness and heroism" of the women soldiers. The regiment lost 35 guns, eighteen killed, 46 wounded, and 74 missing on 23 and 24 August. The 16th Panzer Division's history mentioned its encounter with the regiment, claiming the destruction of 37 guns, and the unit's surprise that its opponents had in part included women.[79][78]

In the early stages of the battle, the NKVD organised poorly armed "Workers' militias" similar to those that had defended the city twenty-four years earlier, composed of civilians not directly involved in war production for immediate use in the battle. The civilians were often sent into battle without rifles.[80] Staff and students from the local technical university formed a "tank destroyer" unit. They assembled tanks from leftover parts at the tractor factory. These tanks, unpainted and lacking gun-sights, were driven directly from the factory floor to the front line. They could only be aimed at point-blank range through the bore of their gun barrels.[81]

By the end of August, Army Group South (B) had finally reached the Volga, north of Stalingrad. Another advance to the river south of the city followed, while the Soviets abandoned their Rossoshka position for the inner defensive ring west of Stalingrad. The wings of the 6th Army and the 4th Panzer Army met near Jablotchni along the Zaritza on 2 Sept.[82] By 1 September, the Soviets could only reinforce and supply their forces in Stalingrad by perilous crossings of the Volga under constant bombardment by artillery and aircraft.

September city battles

On 5 September, the Soviet 24th and 66th Armies organized a massive attack against XIV Panzer Corps. The Luftwaffe helped repel the offensive by heavily attacking Soviet artillery positions and defensive lines. The Soviets were forced to withdraw at midday after only a few hours. Of the 120 tanks the Soviets had committed, 30 were lost to air attack.[83]

Soviet operations were constantly hampered by the Luftwaffe. On 18 September, the Soviet 1st Guards and 24th Army launched an offensive against VIII Army Corps at Kotluban. VIII. Fliegerkorps dispatched multiple waves of Stuka dive-bombers to prevent a breakthrough. The offensive was repelled. The Stukas claimed 41 of the 106 Soviet tanks knocked out that morning, while escorting Bf 109s destroyed 77 Soviet aircraft.[84] Amid the debris of the wrecked city, the Soviet 62nd and 64th Armies, which included the Soviet 13th Guards Rifle Division, anchored their defence lines with strong-points in houses and factories.

Fighting within the ruined city was fierce and desperate. Lieutenant General Alexander Rodimtsev was in charge of the 13th Guards Rifle Division, and received one of two Heroes of the Soviet Union awarded during the battle for his actions. Stalin's Order No. 227 of 27 July 1942 decreed that all commanders who ordered unauthorised retreats would be subject to a military tribunal.[85] Blocking detachments composed of NKVD or regular troops were positioned behind Red Army units to prevent desertion and straggling, sometimes executing deserters and perceived malingerers.[86] During the battle the 62nd Army had the most arrests and executions: 203 in all, of which 49 were executed, while 139 were sent to penal companies and battalions.[87][88][89][90] Blocking detachments of the Stalingrad and Don Fronts detained 51,758 men from the beginning of the battle to 15 October, with the majority returned to their units. Of those detained, the vast majority of which were from the Don Front, 980 were executed, and 1,349 sent to penal companies.[91][92][93][94] In the two day period between 13 and 15 September, the 62nd Army blocking detachment detained 1,218 men, returning most to their units while shooting 21 men and arresting ten.[95] Beevor claims that 13,500 Soviet soldiers were executed by Soviet authorities at Stalingrad,[96] however, this claim is disputed by Hellbeck.[97]

By 12 September, at the time of their retreat into the city, the Soviet 62nd Army had been reduced to 90 tanks, 700 mortars and just 20,000 personnel.[98] The remaining tanks were used as immobile strong-points within the city. The initial German attack on 14 September attempted to take the city in a rush. The 51st Army Corps' 295th Infantry Division went after the Mamayev Kurgan hill, the 71st attacked the central rail station and toward the central landing stage on the Volga, while 48th Panzer Corps attacked south of the Tsaritsa River. Though initially successful, the German attacks stalled in the face of Soviet reinforcements brought in from across the Volga. Rodimtsev's 13th Guards Rifle Division had been hurried up to cross the river and join the defenders inside the city.[99] Assigned to counterattack at the Mamayev Kurgan and at Railway Station No. 1, it suffered particularly heavy losses. Despite their losses, Rodimtsev's troops were able to inflict similar damage on their opponents. By 26 September, the opposing 71st Infantry Division had half of its battalions considered exhausted, reduced from all of them being considered average in combat capability when the attack began twelve days earlier.[100]

The brutality of the battle was noted in a journal found on German lieutenant Weiner:[101]

The street is no longer measured by meters but by corpses…Stalingrad is no longer a town. By day it is an enormous cloud of burning, blinding smoke; it is a vast furnace lit by the reflection of the flames. And when night arrives, one of those scorching howling bleeding nights, the dogs plunge into the Volga and swim desperately to gain the other bank. The nights of Stalingrad are a terror for them. Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for long; only men endure.

A ferocious battle raged for several days at the giant grain elevator in the south of the city.[102] About fifty Red Army defenders, cut off from resupply, held the position for five days and fought off ten different assaults before running out of ammunition and water.[103] Only forty dead Soviet fighters were found, though the Germans had thought there were many more due to the intensity of resistance. The Soviets burned large amounts of grain during their retreat in order to deny the enemy food. Paulus chose the grain elevator and silos as the symbol of Stalingrad for a patch he was having designed to commemorate the battle after a German victory.[103]

In another part of the city, a Soviet platoon under the command of Sergeant Yakov Pavlov fortified a four-story building that oversaw a square 300 meters from the river bank, later called Pavlov's House. The soldiers surrounded it with minefields, set up machine-gun positions at the windows and breached the walls in the basement for better communications.[98] The soldiers found about ten Soviet civilians hiding in the basement. They were not relieved, and not significantly reinforced, for two months. The building was labelled Festung ("Fortress") on German maps. Sgt. Pavlov was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union for his actions.

Stubborn defenses of semi-fortified buildings in the center of the city cost the Germans countless soldiers. A violent battle occurred for the Univermag department store on Red Square, which served as the headquarters of the 1st Battalion of the 13th Guards Rifle Division's 42nd Guards Rifle Regiment. Another battle occurred for a nearby warehouse dubbed the "nail factory". In a three-story building close by, guardsmen fought on for five days, their noses and throats filled with brick dust from pulverized walls, with only six out of close to half a battalion escaping alive.[104]

The Germans made slow but steady progress through the city. Positions were taken individually, but the Germans were never able to capture the key crossing points along the river bank. By 27 Sept. the Germans occupied the southern portion of the city, but the Soviets held the centre and northern part. Most importantly, the Soviets controlled the ferries to their supplies on the east bank of the Volga.[105]

Strategy and tactics

German military doctrine was based on the principle of combined-arms teams and close cooperation between tanks, infantry, engineers, artillery and ground-attack aircraft. To negate the German usage of tanks and artillery in the ruins of the city, Soviet commander Vasily Chuikov introduced a tactic he described as "hugging" the enemy: keeping Soviet front-line positions as close as possible to those of the Germans so that German artillery and aircraft could not attack without risking friendly fire.[106][107] After mid-September, to reduce casualties, he ceased launching organized daylight counterattacks, instead emphasizing small unit tactics in which Soviet infantry moved through the city's sewers to strike into the rear of attacking German units.[108] The Soviets preferred night attacks, which disrupted German morale by depriving them of sleep. Soviet reconnaissance patrols were used to find German positions and take prisoners for interrogation, enabling them to anticipate attacks. When Soviet troops detected a coming attack, they launched their own counterattacks at dawn before German air support could arrive. Soviet troops blunted the German attacks themselves through ambushes that separated tanks from their supporting infantry, as well as the employment of booby traps and mines. These tactical innovations became widespread as the battle continued.[109] According to Beevor, "Red Army soldiers enjoyed inventing gadgets to kill Germans. New booby traps were dreamed up, each seemingly more ingenious and unpredictable in its results than the last."[110]

An important weapon during the battle was the flamethrower, which was "effectively terrifying" in its use of clearing sewer tunnels, cellars, and inaccessible hiding places.[110] The operators of the weapon were immediately targeted as soon as they were spotted.[110]

The Soviet urban warfare tactics relied on 20-to-50-man-assault groups, armed with machine guns, grenades and satchel charges, and buildings fortified as strongpoints with clear fields of fire. While the strongpoints were defended by guns or tanks on the ground floor, machine gunners and artillery observers operated from the upper floors. Meanwhile, assault groups used sewers or broke through walls into adjoining buildings to maintain concealment while moving into the rear of German attacks. Glantz summarizes Soviet tactical innovations as a "combination of intelligence, discipline, and determination" enabling the Soviet defenders to keep fighting when the Germans had achieved victory by "all conventional measures."[109]

The Red Army gradually adopted a strategy to hold for as long as possible all the ground in the city. Thus, they converted multi-floored apartment blocks, factories, warehouses, street corner residences and office buildings into a series of well-defended strong-points with small 5–10-man units. Manpower in the city was constantly refreshed by bringing additional troops over the Volga. When a position was lost, an immediate attempt was usually made to re-take it with fresh forces.

Bitter fighting raged for ruins, streets, factories, houses, basements, and staircases.[24] Blocks and buildings would change hands numerous times through intense hand-to-hand fighting.[111][112] Even the sewers were the sites of firefights. The Germans called this unseen urban warfare Rattenkrieg ("Rat War"),[113] and bitterly joked about capturing the kitchen but still fighting for the living room and the bedroom. Buildings had to be cleared room by room through the bombed-out debris of residential areas, office blocks, basements and apartment high-rises. Beevor describes how this process was particularly brutal, stating that, "In its way, the fighting in Stalingrad was even more terrifying than the impersonal slaughter at Verdun. The close-quarter combat in ruined buildings, bunkers, cellars and sewers was soon dubbed 'Rattenkrieg' by German soldiers. It possessed a savage intimacy which appalled their generals, who felt that they were rapidly losing control over events."[114] Some of the taller buildings, blasted into roofless shells by earlier German aerial bombardment, saw floor-by-floor, close-quarters combat, with the Germans and Soviets on alternate levels, firing at each other through holes in the floors. Fighting on and around Mamayev Kurgan, a prominent hill above the city, was particularly merciless; indeed, the position changed hands many times.[115][116] Gerhardt's Mill was a noticeable building that was brutally fought for, and is kept till this day as a memorial to the battle. It was eventually cleared by the 39th Guards Regiment in pitiless close-quarters combat.[117]

The brutality of the close-quarters combat was shown by the number of military casualties taken by units. The 13th Guards Rifle Division suffered 30% casualties in the first twenty-four hours, with only 320 men out of 10,000 remaining at the battle's conclusion.[117] With buildings and floors changing hands dozens of times and taking up to several days to win, platoons and companies took up to 90% and even 100% casualties to win a building or floor within it.[24]

The Germans used aircraft, tanks and heavy artillery to clear the city with varying degrees of success. Toward the end of the battle, the gigantic railroad gun nicknamed Dora was brought into the area. The Soviets built up a large number of artillery batteries on the east bank of the Volga. This artillery was able to bombard the German positions or at least provide counter-battery fire.

Snipers on both sides used the ruins to inflict casualties, with the Soviet command heavily emphasizing sniper tactics to wear down the Germans. The most famous Soviet sniper in Stalingrad was Vasily Zaytsev, who became a propaganda hero,[109] credited with 225 kills during the battle. Targets were often soldiers bringing up food or water to forward positions. Artillery spotters were an especially prized target for snipers.[118]

A significant historical debate concerns the degree of terror in the Red Army. The British historian Antony Beevor noted the "sinister" message from the Stalingrad Front's Political Department on 8 October 1942 that: "The defeatist mood is almost eliminated and the number of treasonous incidents is getting lower" as an example of the sort of coercion Red Army soldiers experienced under the Special Detachments (later to be renamed SMERSH).[119] On the other hand, Beevor noted the often extraordinary bravery of the Soviet soldiers in a battle that was only comparable to Verdun, and argued that terror alone cannot explain such self-sacrifice.[120] A Soviet officer interviewed, Nikolai Aksyonov, explained the general feeling amongst the Soviets in Stalingrad, "There was this sense that every soldier and officer in Stalingrad was itching to kill as many Germans as possible. In Stalingrad people felt a particularly intense hatred for the Germans."[121]

Richard Overy addresses the question of just how important the Red Army's coercive methods were to the Soviet war effort compared with other motivational factors such as hatred for the enemy. He argues that, though it is "easy to argue that from the summer of 1942 the Soviet army fought because it was forced to fight," to concentrate solely on coercion is nonetheless to "distort our view of the Soviet war effort."[122] After conducting hundreds of interviews with Soviet veterans on the subject of terror on the Eastern Front – and specifically about Order No. 227 ("Not a step back!") at Stalingrad – Catherine Merridale notes that, seemingly paradoxically, "their response was frequently relief."[123] Infantryman Lev Lvovich's explanation, for example, is typical for these interviews; as he recalls, "[i]t was a necessary and important step. We all knew where we stood after we had heard it. And we all – it's true – felt better. Yes, we felt better."[123]

Many women fought on the Soviet side or were under fire. As General Chuikov acknowledged, "Remembering the defence of Stalingrad, I can't overlook the very important question … about the role of women in war, in the rear, but also at the front. Equally with men they bore all the burdens of combat life and together with us men, they went all the way to Berlin."[124] At the beginning of the battle there were 75,000 women and girls from the Stalingrad area who had finished military or medical training, and all of whom were to serve in the battle.[125] Women staffed a great many of the anti-aircraft batteries that fought not only the Luftwaffe but German tanks.[126] Soviet nurses not only treated wounded personnel under fire but were involved in the highly dangerous work of bringing wounded soldiers back to the hospitals under enemy fire.[127] Many of the Soviet wireless and telephone operators were women who often suffered heavy casualties when their command posts came under fire.[128] Though women were not usually trained as infantry, many Soviet women fought as machine gunners, mortar operators, and scouts.[129] Women were also snipers at Stalingrad.[130] Three air regiments at Stalingrad were entirely female.[129] At least three women won the title Hero of the Soviet Union while driving tanks at Stalingrad.[131]

For both Stalin and Hitler, Stalingrad became a matter of prestige far beyond its strategic significance.[132] The Soviet command moved units from the Red Army strategic reserve in the Moscow area to the lower Volga and transferred aircraft from the entire country to the Stalingrad region.

The strain on both military commanders was immense: Paulus developed an uncontrollable tic in his eye, which eventually affected the left side of his face, while Chuikov experienced an outbreak of eczema that required him to have his hands completely bandaged. Troops on both sides faced the constant strain of close-range combat.[133]

The Soviets used psychological warfare tactics to intimidate and demoralize German forces. On loudspeakers throughout the ruined city, they would announce "Every seven seconds a German soldier dies. Stalingrad. . .mass grave".[134][135] The sound was interspersed with the monotonous sound of a ticking clock, and an orchestral melody dubbed the "Tango of Death".[135]

Fighting in the industrial district

After 27 September, much of the fighting in the city shifted north to the industrial district. Having slowly advanced over 10 days against strong Soviet resistance, the 51st Army Corps was finally in front of the three giant factories of Stalingrad: the Red October Steel Factory, the Barrikady Arms Factory and Stalingrad Tractor Factory. It took a few more days for them to prepare for the most savage offensive of all, which was unleashed on 14 October.[136] According to Beevor about the danger of the factories, he states, "The Red October complex and Barrikady gun factory had been turned into fortresses as lethal as those of Verdun. If anything, they were more dangerous because the Soviet regiments were so well hidden."[133] The danger of the Barrikady Arms Factory was made apparent firsthand by sergeant Ernst Wohlfahrt, who witnessed 18 German pioneers get killed by a Russian booby trap.[137] Exceptionally intense shelling and bombing paved the way for the first German assault groups. The main attack (led by the 14th Panzer and 305th Infantry Divisions) attacked towards the tractor factory, while another assault led by the 24th Panzer Division hit to the south of the giant plant.[138]

The German onslaught crushed the 37th Guards Rifle Division of Major General Viktor Zholudev and in the afternoon the forward assault group reached the tractor factory before arriving at the Volga River, splitting the 62nd Army into two.[139] In response to the German breakthrough to the Volga, the front headquarters committed three battalions from the 300th Rifle Division and the 45th Rifle Division of Colonel Vasily Sokolov, a substantial force of over 2,000 men, to the fighting at the Red October Factory.[140]

Fighting raged inside the Barrikady Factory until the end of October.[141] The Soviet-controlled area shrank down to a few strips of land along the western bank of the Volga, and in November the fighting concentrated around what Soviet newspapers referred to as "Lyudnikov's Island", a small patch of ground behind the Barrikady Factory where the remnants of Colonel Ivan Lyudnikov's 138th Rifle Division resisted all ferocious assaults thrown by the Germans and became a symbol of the stout Soviet defence of Stalingrad.[142]

Air attacks

From 5 to 12 September, Luftflotte 4 conducted 7,507 sorties (938 per day). From 16 to 25 September, it carried out 9,746 missions (975 per day).[143] Determined to crush Soviet resistance, Luftflotte 4's Stukawaffe flew 900 individual sorties against Soviet positions at the Stalingrad Tractor Factory on 5 October. Several Soviet regiments were wiped out; the entire staff of the Soviet 339th Infantry Regiment was killed the following morning during an air raid.[144]

The Luftwaffe retained air superiority into November, and Soviet daytime aerial resistance was nonexistent. However, the combination of constant air support operations on the German side and the Soviet surrender of the daytime skies began to affect the strategic balance in the air. From 28 June to 20 September, Luftflotte 4's original strength of 1,600 aircraft, of which 1,155 were operational, fell to 950, of which only 550 were operational. The fleet's total strength decreased by 40 percent. Daily sorties decreased from 1,343 per day to 975 per day. Soviet offensives in the central and northern portions of the Eastern Front tied down Luftwaffe reserves and newly built aircraft, reducing Luftflotte 4's percentage of Eastern Front aircraft from 60 percent on 28 June to 38 percent by 20 September. The Kampfwaffe (bomber force) was the hardest hit, having only 232 out of an original force of 480 left.[143] The VVS remained qualitatively inferior, but by the time of the Soviet counter-offensive, the VVS had reached numerical superiority.

In mid-October, after receiving reinforcements from the Caucasus theatre, the Luftwaffe intensified its efforts against the remaining Red Army positions holding the west bank. Luftflotte 4 flew 1,250 sorties on 14 October and its Stukas dropped 550 tonnes of bombs, while German infantry surrounded the three factories.[145] Stukageschwader 1, 2, and 77 had largely silenced Soviet artillery on the eastern bank of the Volga before turning their attention to the shipping that was once again trying to reinforce the narrowing Soviet pockets of resistance. The 62nd Army had been cut in two and, due to intensive air attack on its supply ferries, was receiving much less material support. With the Soviets forced into a 1-kilometre (1,000-yard) strip of land on the western bank of the Volga, over 1,208 Stuka missions were flown in an effort to eliminate them.[146]

The Soviet bomber force, the Aviatsiya Dal'nego Deystviya (Long Range Aviation; ADD), having taken crippling losses over the past 18 months, was restricted to flying at night. The Soviets flew 11,317 night sorties over Stalingrad and the Don-bend sector between 17 July and 19 November. These raids caused little damage and were of nuisance value only.[147][148]: 265

On 8 November, substantial units from Luftflotte 4 were withdrawn to combat the Allied landings in North Africa. The German air arm found itself spread thinly across Europe, struggling to maintain its strength in the other southern sectors of the Soviet-German front.[Note 9]

As historian Chris Bellamy notes, the Germans paid a high strategic price for the aircraft sent into Stalingrad: the Luftwaffe was forced to divert much of its air strength away from the oil-rich Caucasus, which had been Hitler's original grand-strategic objective.[149]

The Royal Romanian Air Force was also involved in the Axis air operations at Stalingrad. Starting 23 October 1942, Romanian pilots flew a total of 4,000 sorties, during which they destroyed 61 Soviet aircraft. The Romanian Air Force lost 79 aircraft, most of them captured on the ground along with their airfields.[150]

Medical and food conditions

The conditions of both armies during the battle was atrocious. Disease ran rampant on both sides, with many deaths due to dysentery, typhus, diphtheria, tuberculosis and jaundice, causing medical staff to fear a possible epidemic.[151] Vermin such as rats and mice were plentiful on the battlefield, serving as one reason the Germans could not counterattack in time, due to mice having chewed their tank wiring.[151] Lice were also heavily prevalent, and plagues of flies would gather around kitchens, adding to the possibility of wound infections. The brutal winter conditions affected soldiers tremendously,[24] with temperatures at times reaching as low as −40 °C in late November,[32] or −30 °C in late January.[151] The conditions caused rapid frostbite with many cases of gangrene and eventual amputation as a result. The conditions also saw soldiers dying en masse due to frostbite and hypothermia.[151] Both armies also suffered from food shortages, with mass starvation on both sides. Stress, tiredness and cold upset the metabolism of many soldiers, with them receiving a reduced amount of calories from food.[151] The German forces eventually ran out of medical supplies such as ether, antiseptics, bandages and other medical supplies. With the shortages, surgery had to be done without anaesthesia.[151]

Germans reach the Volga

After three months of slow advance, the Germans finally reached the river banks, capturing 90% of the ruined city and splitting the remaining Soviet forces into two narrow pockets. Ice floes on the Volga now prevented boats and tugs from supplying the Soviet defenders. Nevertheless, the fighting continued, especially on the slopes of Mamayev Kurgan and inside the factory area in the northern part of the city.[152] From 21 August to 20 November, the German 6th Army lost 60,548 men, including 12,782 killed, 45,545 wounded and 2,221 missing.[153]

Soviet counter-offensives

Recognising that German troops were ill-prepared for offensive operations during the winter of 1942 and that most of them were redeployed elsewhere on the southern sector of the Eastern Front, the Stavka decided to conduct a number of offensive operations between 19 November 1942 and 2 February 1943. These operations opened the Winter Campaign of 1942–1943 (19 November 1942 – 3 March 1943), which involved some fifteen Armies operating on several fronts. According to Zhukov, "German operational blunders were aggravated by poor intelligence: they failed to spot preparations for the major counter-offensive near Stalingrad where there were 10 field, 1 tank and 4 air armies."[154]

Weakness on the Axis flanks

During the siege, the German and allied Italian, Hungarian, and Romanian armies protecting Army Group B's north and south flanks had pressed their headquarters for support. The Hungarian 2nd Army was given the task of defending a 200 km (120 mi) section of the front north of Stalingrad between the Italian Army and Voronezh. This resulted in a very thin line, with some sectors where 1–2 km (0.62–1.24 mi) stretches were being defended by a single platoon (platoons typically have around 20 to 50 men). These forces were also lacking in effective anti-tank weapons. Zhukov states, "Compared with the Germans, the troops of the satellites were not so well armed, less experienced and less efficient, even in defence."[155]

Because of the total focus on the city, the Axis forces had neglected for months to consolidate their positions along the natural defensive line of the Don River. The Soviet forces were allowed to retain bridgeheads on the right bank from which offensive operations could be quickly launched. These bridgeheads in retrospect presented a serious threat to Army Group B.[50]

Similarly, on the southern flank of the Stalingrad sector, the front southwest of Kotelnikovo was held only by the Romanian 4th Army. Beyond that army, a single German division, the 16th Motorised Infantry, covered 400 km. Paulus had requested permission on 10 November to "withdraw the 6th Army behind the Don," but was rejected.[156] According to Paulus's comments to his adjutant Wilhelm Adam, "There is still the order whereby no commander of an army group or an army has the right to relinquish a village, even a trench, without Hitler's consent."[157]

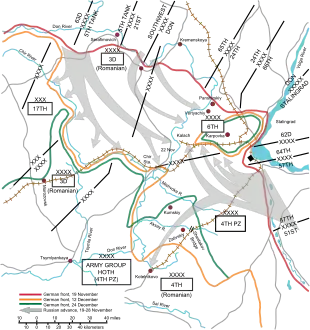

Operation Uranus

In autumn, Zhukov and Vasilevsky, responsible for strategic planning in the Stalingrad area, concentrated forces in the steppes to the north and south of the city. The northern flank was defended by Hungarian and Romanian units, often in open positions on the steppes. The natural line of defence, the Don River, had never been properly established by the German side. The armies in the area were also poorly equipped in terms of anti-tank weapons. The plan was to punch through the overstretched and weakly defended German flanks and surround the German forces in the Stalingrad region.

During the preparations for the attack, Marshal Zhukov personally visited the front and noticing the poor organisation, insisted on a one-week delay in the start date of the planned attack.[158] The operation was code-named "Uranus" and launched in conjunction with Operation Mars, which was directed at Army Group Center about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) to the northwest. The plan was similar to the one Zhukov had used to achieve victory at Khalkhin Gol three years before, where he had sprung a double envelopment and destroyed the 23rd Division of the Japanese army.[159]

On 19 November 1942, the Red Army launched Operation Uranus. The attacking Soviet units under the command of Gen. Nikolay Vatutin consisted of three complete armies, the 1st Guards Army, 5th Tank Army and 21st Army, including a total of 18 infantry divisions, eight tank brigades, two motorised brigades, six cavalry divisions and one anti-tank brigade. The preparations for the attack could be heard by the Romanians, who continued to push for reinforcements, only to be refused again. Thinly spread, deployed in exposed positions, outnumbered and poorly equipped, the Romanian 3rd Army, which held the northern flank of the German 6th Army, was overrun.

Behind the front lines, no preparations had been made to defend key points in the rear such as Kalach. The response by the Wehrmacht was both chaotic and indecisive. Poor weather prevented effective air action against the Soviet offensive. Army Group B was in disarray and faced strong Soviet pressure across all its fronts. Hence it was ineffective in relieving the 6th Army.

On 20 November, a second Soviet offensive (two armies) was launched to the south of Stalingrad against points held by the Romanian 4th Army Corps. The Romanian forces, made up primarily of infantry, were overrun by large numbers of tanks. The Soviet forces raced west and met on 23 November at the town of Kalach, sealing the ring around Stalingrad.[160] The link-up of the Soviet forces, not filmed at the time, was later re-enacted for a propaganda film which was shown worldwide.

Sixth Army surrounded

The surrounded Axis personnel comprised 265,000 Germans, Romanians, Italians,[161] and Croatians. In addition, the German 6th Army included between 40,000 and 65,000 Hilfswillige (Hiwi), or "volunteer auxiliaries",[162][163] a term used for personnel recruited amongst Soviet POWs and civilians from areas under occupation. Hiwi often proved to be reliable Axis personnel in rear areas and were used for supporting roles, but also served in some front-line units as their numbers had increased.[163]

The conditions of the German 6th Army had been "reduced to conditions very similar to those in the First World War".[164] The most insanitary conditions were found in units who were forced by the Soviets to take up new positions in the open steppe. Beevor explains, "In such conditions, troops had not yet had a chance to dig communications trenches and latrines. Soldiers were sleeping, packed together like sardines, in holes in the ground covered by a tarpaulin. Infections spread rapidly. Dysentery soon had a debilitating and demoralizing effect, as weakened soldiers squatted over shovels in their trenches, then threw the contents out over the parapet."[165]

German personnel in the pocket numbered about 210,000, according to strength breakdowns of the 20 field divisions (average size 9,000) and 100 battalion-sized units of the Sixth Army on 19 November 1942. Inside the pocket (German: Kessel, literally "cauldron"), there were also around 10,000 Soviet civilians and several thousand Soviet soldiers the Germans had taken captive during the battle. Not all of the 6th Army was trapped: 50,000 soldiers were brushed aside outside the pocket. These belonged mostly to the other two divisions of the 6th Army between the Italian and Romanian armies: the 62nd and 298th Infantry Divisions. Of the 210,000 Germans, 10,000 remained to fight on, 105,000 surrendered, 35,000 left by air and the remaining 60,000 died.

Even with the desperate situation of the 6th Army, Army Group A had to hold its position in the Caucasus further south. No troops were pulled off that region to help relieve the 6th Army. Only on December 31, after Soviet forces had broken through German positions in Operation Little Saturn and threatened to retake Rostov-on-Don and cut off Army Group A completely, was it ordered to withdraw from the Caucasus to avoid being trapped.[166]

Army Group Don was formed under Field Marshal von Manstein. Under his command were the twenty German and two Romanian divisions encircled at Stalingrad, Adam's battle groups formed along the Chir River and on the Don bridgehead, plus the remains of the Romanian 3rd Army.[167]

The Red Army units immediately formed two defensive fronts: a circumvallation facing inward and a contravallation facing outward. Field Marshal Erich von Manstein advised Hitler not to order the 6th Army to break out, stating that he could break through the Soviet lines and relieve the besieged 6th Army.[168] The American historians Williamson Murray and Alan Millet wrote that it was Manstein's message to Hitler on 24 November advising him that the 6th Army should not break out, along with Göring's statements that the Luftwaffe could supply Stalingrad that "... sealed the fate of the Sixth Army".[169][170] After 1945, Manstein claimed that he told Hitler that the 6th Army must break out.[168] The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote that Manstein distorted his record on the matter.[171] Manstein was tasked to conduct a relief operation, named Operation Winter Storm (Unternehmen Wintergewitter) against Stalingrad, which he thought was feasible if the 6th Army was temporarily supplied through the air.[172][173]

Adolf Hitler had declared in a public speech (in the Berlin Sportpalast) on 30 September 1942 that the German army would never leave the city. At a meeting shortly after the Soviet encirclement, German army chiefs pushed for an immediate breakout to a new line on the west of the Don, but Hitler was at his Bavarian retreat of Obersalzberg in Berchtesgaden with the head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring. When asked by Hitler, Göring replied, after being convinced by Hans Jeschonnek,[174] that the Luftwaffe could supply the 6th Army with an "air bridge". This would allow the Germans in the city to fight on temporarily while a relief force was assembled.[160] A similar plan had been used a year earlier at the Demyansk Pocket, albeit on a much smaller scale: a corps at Demyansk rather than an entire army.[175]

The director of Luftflotte 4, Wolfram von Richthofen, tried to get this decision overturned. The forces under the 6th Army were almost twice as large as a regular German army unit, plus there was also a corps of the 4th Panzer Army trapped in the pocket. Due to a limited number of available aircraft and having only one available airfield, at Pitomnik, the Luftwaffe could only deliver 105 tonnes of supplies per day, only a fraction of the minimum 750 tonnes that both Paulus and Zeitzler estimated the 6th Army needed.[176][Note 10] To supplement the limited number of Junkers Ju 52 transports, the Germans pressed other aircraft into the role, such as the Heinkel He 177 bomber. Some bombers performed adequately – the Heinkel He 111 proved to be quite capable and was much faster than the Ju 52.[177]

General Richthofen informed Manstein on 27 November of the small transport capacity of the Luftwaffe and the impossibility of supplying 300 tons a day by air. Manstein now saw the enormous technical difficulties of a supply by air of these dimensions. The next day he made a six-page situation report to the general staff. Based on the information of the expert Richthofen, he declared that contrary to the example of the pocket of Demyansk the permanent supply by air would be impossible. If only a narrow link could be established to Sixth Army, he proposed that this should be used to pull it out from the encirclement, and said that the Luftwaffe should instead of supplies deliver only enough ammunition and fuel for a breakout attempt. He acknowledged the heavy moral sacrifice that giving up Stalingrad would mean, but this would be made easier to bear by conserving the combat power of the Sixth Army and regaining the initiative.[177] He ignored the limited mobility of the army and the difficulties of disengaging the Soviets. Hitler reiterated that the Sixth Army would stay at Stalingrad and that the air bridge would supply it until the encirclement was broken by a new German offensive.

Supplying the 270,000 men trapped in the "cauldron" required 700 tons of supplies a day. That would mean 350 Ju 52 flights a day into Pitomnik. At a minimum, 500 tons were required. However, according to Adam, "On not one single day have the minimal essential number of tons of supplies been flown in."[178] The Luftwaffe was able to deliver an average of 85 tonnes of supplies per day out of an air transport capacity of 106 tonnes per day. The most successful day, 19 December, the Luftwaffe delivered 262 tonnes of supplies in 154 flights. The outcome of the airlift was the Luftwaffe's failure to provide its transport units with the tools they needed to maintain an adequate count of operational aircraft – tools that included airfield facilities, supplies, manpower, and even aircraft suited to the prevailing conditions. These factors, taken together, prevented the Luftwaffe from effectively employing the full potential of its transport forces, ensuring that they were unable to deliver the quantity of supplies needed to sustain the 6th Army.[179]

In the early parts of the operation, fuel was shipped at a higher priority than food and ammunition because of a belief that there would be a breakout from the city.[180] Transport aircraft also evacuated technical specialists and sick or wounded personnel from the besieged enclave. Sources differ on the number flown out: at least 25,000 to at most 35,000.

Initially, supply flights came in from the field at Tatsinskaya,[181] called 'Tazi' by the German pilots. On 23 December, the Soviet 24th Tank Corps, commanded by Major-General Vasily Mikhaylovich Badanov, reached nearby Skassirskaya and in the early morning of 24 December, the tanks reached Tatsinskaya. Without any soldiers to defend the airfield, it was abandoned under heavy fire; in a little under an hour, 108 Ju 52s and 16 Ju 86s took off for Novocherkassk – leaving 72 Ju 52s and many other aircraft burning on the ground.

A new base was established some 300 km (190 mi) from Stalingrad at Salsk. The additional distance became another obstacle to the resupply efforts. Salsk was abandoned in turn by mid-January for a rough facility at Zverevo, near Shakhty. The field at Zverevo was attacked repeatedly on 18 January and a further 50 Ju 52s were destroyed. Winter weather conditions, technical failures, heavy Soviet anti-aircraft fire and fighter interceptions eventually led to the loss of 488 German aircraft.

In spite of the failure of the German offensive to reach the 6th Army, the air supply operation continued under ever more difficult circumstances. The 6th Army slowly starved. General Zeitzler, moved by their plight, began to limit himself to their slim rations at meal times. After a few weeks on such a diet, he had "visibly lost weight", according to Albert Speer, and Hitler "commanded Zeitzler to resume at once taking sufficient nourishment".[182]

The toll on the Transportgruppen was heavy. 160 aircraft were destroyed and 328 were heavily damaged (beyond repair). Some 266 Junkers Ju 52s were destroyed; one-third of the fleet's strength on the Eastern Front. The He 111 gruppen lost 165 aircraft in transport operations. Other losses included 42 Ju 86s, 9 Fw 200 Condors, 5 He 177 bombers and 1 Ju 290. The Luftwaffe also lost close to 1,000 highly experienced bomber crew personnel.[183] So heavy were the Luftwaffe's losses that four of Luftflotte 4's transport units (KGrzbV 700, KGrzbV 900, I./KGrzbV 1 and II./KGzbV 1) were "formally dissolved".[67]

End of the battle

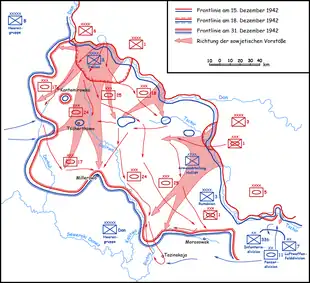

Operation Winter Storm

Manstein's plan to rescue the Sixth Army – Operation Winter Storm – was developed in full consultation with Führer headquarters. It aimed to break through to the Sixth Army and establish a corridor to keep it supplied and reinforced, so that, according to Hitler's order, it could maintain its "cornerstone" position on the Volga, "with regard to operations in 1943". Manstein, however, who knew that Sixth Army could not survive the winter there, instructed his headquarters to draw up a further plan in the event of Hitler's seeing sense.

This would include the subsequent breakout of Sixth Army, in the event of a successful first phase, and its physical reincorporation in Army Group Don. This second plan was given the name Operation Thunderclap. Winter Storm, as Zhukov had predicted, was originally planned as a two-pronged attack. One thrust would come from the area of Kotelnikovo, well to the south, and around 160 kilometres (100 mi) from the Sixth Army. The other would start from the Chir front west of the Don, which was little more than 60 kilometres (40 mi) from the edge of the Kessel, but the continuing attacks of Romanenko's 5th Tank Army against the German detachments along the river Chir ruled out that start-line.

This left only the LVII Panzer Corps around Kotelnikovo, supported by the rest of Hoth's very mixed Fourth Panzer Army, to relieve Paulus's trapped divisions. The LVII Panzer Corps, commanded by General Friedrich Kirchner, had been weak at first. It consisted of two Romanian cavalry divisions and the 23rd Panzer Division, which mustered no more than thirty serviceable tanks. The 6th Panzer Division, arriving from France, was a vastly more powerful formation, but its members hardly received an encouraging impression. The Austrian divisional commander, General Erhard Raus, was summoned to Manstein's royal carriage in Kharkov station on 24 November, where the field marshal briefed him. "He described the situation in very sombre terms", recorded Raus.

Three days later, when the first trainload of Raus's division steamed into Kotelnikovo station to unload, his troops were greeted by "a hail of shells" from Soviet batteries. "As quick as lightning, the Panzergrenadiers jumped from their wagons. But already the enemy was attacking the station with their battle-cries of 'Urrah!'"

By 18 December, the German Army had pushed to within 48 km (30 mi) of Sixth Army's positions. However, the predictable nature of the relief operation brought significant risk for all German forces in the area. The starving encircled forces at Stalingrad made no attempt to break out or link up with Manstein's advance. Some German officers requested that Paulus defy Hitler's orders to stand fast and instead attempt to break out of the Stalingrad pocket. Paulus refused, concerned about the Red Army attacks on the flank of Army Group Don and Army Group B in their advance on Rostov-on-Don, "an early abandonment" of Stalingrad "would result in the destruction of Army Group A in the Caucasus", and the fact that his 6th Army tanks only had fuel for a 30 km advance towards Hoth's spearhead, a futile effort if they did not receive assurance of resupply by air. Of his questions to Army Group Don, Paulus was told, "Wait, implement Operation 'Thunderclap' only on explicit orders!" – Operation Thunderclap being the code word initiating the breakout.[184]

Operation Little Saturn

On 16 December, the Soviets launched Operation Little Saturn, which attempted to punch through the Axis army (mainly Italians) on the Don. The Germans set up a "mobile defence" of small units that were to hold towns until supporting armour arrived. From the Soviet bridgehead at Mamon, 15 divisions – supported by at least 100 tanks – attacked the Italian Cosseria and Ravenna Divisions, and although outnumbered 9 to 1, the Italians initially fought well, with the Germans praising the quality of the Italian defenders,[185] but on 19 December, with the Italian lines disintegrating, ARMIR headquarters ordered the battered divisions to withdraw to new lines.[186]

The fighting forced a total revaluation of the German situation. Sensing that this was the last chance for a breakout, Manstein pleaded with Hitler on 18 December, but Hitler refused. Paulus himself also doubted the feasibility of such a breakout. The attempt to break through to Stalingrad was abandoned and Army Group A was ordered to pull back from the Caucasus. The 6th Army now was beyond all hope of German relief. While a motorised breakout might have been possible in the first few weeks, the 6th Army now had insufficient fuel and the German soldiers would have faced great difficulty breaking through the Soviet lines on foot in harsh winter conditions. But in its defensive position on the Volga, the 6th Army continued to tie down a significant number of Soviet Armies.[187]

On 23 December, the attempt to relieve Stalingrad was abandoned and Manstein's forces switched over to the defensive to deal with new Soviet offensives.[188] As Zhukov states,

The military and political leadership of Nazi Germany sought not to relieve them, but to get them to fight on for as long possible so as to tie up the Soviet forces. The aim was to win as much time as possible to withdraw forces from the Caucasus (Army Group A) and to rush troops from other Fronts to form a new front that would be able in some measure to check our counter-offensive.[189]

Soviet victory

The Red Army High Command sent three envoys while simultaneously aircraft and loudspeakers announced terms of capitulation on 7 January 1943. The letter was signed by Colonel-General of Artillery Voronov and the commander-in-chief of the Don Front, Lieutenant-General Rokossovsky. A low-level Soviet envoy party (comprising Major Aleksandr Smyslov, Captain Nikolay Dyatlenko and a trumpeter) carried generous surrender terms to Paulus: if he surrendered within 24 hours, he would receive a guarantee of safety for all prisoners, medical care for the sick and wounded, prisoners being allowed to keep their personal belongings, "normal" food rations, and repatriation to any country they wished after the war. Rokossovsky's letter also stressed that Paulus' men were in an untenable situation. Paulus requested permission to surrender, but Hitler rejected Paulus' request out of hand. Accordingly, Paulus did not respond.[190][191] The German High Command informed Paulus, "Every day that the army holds out longer helps the whole front and draws away the Russian divisions from it."[192]

The Germans inside the pocket retreated from the suburbs of Stalingrad to the city itself. The loss of the two airfields, at Pitomnik on 16 January 1943 and Gumrak on the night of 21/22 January,[193] meant an end to air supplies and to the evacuation of the wounded.[194] The third and last serviceable runway was at the Stalingradskaya flight school, which reportedly had the last landings and takeoffs on 23 January.[70] After 23 January, there were no more reported landings, just intermittent air drops of ammunition and food until the end.[195]

The Germans were now not only starving but running out of ammunition. Nevertheless, they continued to resist, in part because they believed the Soviets would execute any who surrendered. Postwar German historians emphasized the fatigue and defeatism that prevailed in the Germans towards the end of the battle. However, transcripts show that despite many German soldiers yelling "Hitler kaput" to avoid being shot while surrendering, the level of armed resistance remained extraordinarily high till the end of the battle.[196] In particular, the so-called HiWis, Soviet citizens fighting for the Germans, had no illusions about their fate if captured. The Soviets were initially surprised by the number of Germans they had trapped and had to reinforce their encircling troops. Bloody urban warfare began again in Stalingrad, but this time it was the Germans who were pushed back to the banks of the Volga. The Germans adopted a simple defence of fixing wire nets over all windows to protect themselves from grenades. The Soviets responded by fixing fish hooks to the grenades so they stuck to the nets when thrown. The Germans had no usable tanks in the city, and those that still functioned could, at best, be used as makeshift pillboxes. The Soviets did not bother employing tanks in areas where urban destruction restricted their mobility.

On 22 January, Rokossovsky once again offered Paulus a chance to surrender. Paulus requested that he be granted permission to accept the terms. He told Hitler that he was no longer able to command his men, who were without ammunition or food.[197] Hitler rejected it on a point of honour. He telegraphed the 6th Army later that day, claiming that it had made a historic contribution to the greatest struggle in German history and that it should stand fast "to the last soldier and the last bullet". Hitler told Goebbels that the plight of the 6th Army was a "heroic drama of German history".[198] On 24 January, in his radio report to Hitler, Paulus reported: "18,000 wounded without the slightest aid of bandages and medicines."[199]

On 26 January 1943, the German forces inside Stalingrad were split into two pockets north and south of Mamayev-Kurgan. The northern pocket consisting of the VIIIth Corps, under General Walter Heitz, and the XIth Corps, was now cut off from telephone communication with Paulus in the southern pocket. Now "each part of the cauldron came personally under Hitler".[200] On 28 January, the cauldron was split into three parts. The northern cauldron consisted of the XIth Corps, the central with the VIIIth and LIst Corps, and the southern with the XIVth Panzer Corps and IVth Corps "without units". The sick and wounded reached 40,000 to 50,000.[201]

On 30 January 1943, the 10th anniversary of Hitler's coming to power, Goebbels read out a proclamation that included the sentence: "The heroic struggle of our soldiers on the Volga should be a warning for everybody to do the utmost for the struggle for Germany's freedom and the future of our people, and thus in a wider sense for the maintenance of our entire continent."[202] The same day, Hermann Göring broadcast from the air ministry, comparing the situation of the surrounded German 6th Army to that of the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae, the speech was not well received by soldiers however.[203] Paulus notified Hitler that his men would likely collapse before the day was out. In response, Hitler issued a tranche of field promotions to the Sixth Army's officers. He promoted Paulus to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall. In deciding to promote Paulus, Hitler noted that there was no record of a German or Prussian field marshal having ever surrendered. The implication was clear: if Paulus surrendered, he would shame himself and would become the highest-ranking German officer ever to be captured. Hitler believed that Paulus would either fight to the last man or commit suicide.[204]

On the next day, the southern pocket in Stalingrad collapsed. Soviet forces reached the entrance to the German headquarters in the ruined GUM department store.[205] Major Anatoly Soldatov described the conditions of the department store basement as such, "it was unbelievably filthy, you couldn't get through the front or back doors, the filth came up to your chest, along with human waste and who knows what else. The stench was unbelievable."[206] When interrogated by the Soviets, Paulus claimed that he had not surrendered. He said that he had been taken by surprise. He denied that he was the commander of the remaining northern pocket in Stalingrad and refused to issue an order in his name for them to surrender.[207][208]

There was no one with a camera present to film the capture of Paulus. One person, though, Roman Karmen, managed to record the first interrogation of Paulus that took place the same day, at Shumilov's 64th Army's HQ, and a few hours later at Rokossovsky's Don Front HQ.[209]

The central pocket, under the command of Heitz, surrendered the same day, while the northern pocket, under the command of General Karl Strecker, held out for two more days.[210] Four Soviet armies were deployed against the northern pocket. At four in the morning on 2 February, Strecker was informed that one of his own officers had gone to the Soviets to negotiate surrender terms. Seeing no point in continuing, he sent a radio message saying that his command had done its duty and fought to the last man. When Strecker finally surrendered, he and his chief of staff, Helmuth Groscurth, drafted the final signal sent from Stalingrad, purposely omitting the customary exclamation to Hitler, replacing it with "Long live Germany!"[211]

Around 91,000 exhausted, ill, wounded, and starving prisoners were taken. The prisoners included 22 generals. Hitler was furious and confided that Paulus "could have freed himself from all sorrow and ascended into eternity and national immortality, but he prefers to go to Moscow".[212]

Casualties

The Axis suffered 747,300–1,068,374 combat casualties (killed, wounded or captured) among all branches of the German armed forces and their allies:

- 282,606 in the 6th Army from 21 August to the end of the battle; 17,293 in the 4th Panzer Army from 21 August to 31 January; 55,260 in the Army Group Don from 1 December 1942 to the end of the battle (12,727 killed, 37,627 wounded and 4,906 missing)[153][213] Walsh estimates the losses to 6th Army and 4th Panzer division were over 300,000; including other German army groups between late June 1942 and February 1943, total German casualties were over 600,000.[12] However, Walsh includes in the casualties of German troops the casualties of the Army Group A, which did not take part in the Battle of Stalingrad, but advanced into the Caucasus and participated in the Battle of the Caucasus. Thus, 600,000 German casualties is a greatly exaggerated figure. Louis A. DiMarco estimated the German suffered 400,000 total casualties (killed, wounded or captured) during this battle.[11]

- According to Frieser, et al.: 109,000 Romanians casualties (from November 1942 to December 1942), included 70,000 captured or missing. 114,000 Italians and 105,000 Hungarians were killed, wounded or captured (from December 1942 to February 1943).[13]

- According to Stephen Walsh: Romanian casualties were 158,854; 114,520 Italians (84,830 killed, missing and 29,690 wounded); and 143,000 Hungarian (80,000 killed, missing and 63,000 wounded).[214] Losses among Soviet POW turncoats Hiwis, or Hilfswillige range between 19,300 and 52,000.[14]

235,000 German and allied troops in total, from all units, including Manstein's ill-fated relief force, were captured during the battle.[215]

It is estimated that as many as over 1 million soldiers and civilians combined were killed during the battle.[216][217][218][18] Author William Craig, while researching for his book, stressed the incredible death toll of the battle, "Most appalling was the growing realization, formed by statistics I uncovered, that the battle was the greatest military bloodbath in recorded history. Well over a million men and women died because of Stalingrad, a number far surpassing the previous records of dead at the first battle of the Somme and Verdun in 1916."[216] Historian Jochen Hellbeck described the lethality of the battle as such, "The battle of Stalingrad—the most ferocious and lethal battle in human history—ended on February 2. With an estimated death toll in an excess of a million, the bloodletting at Stalingrad far exceeded that of Verdun, one of the costliest battles of World War I."[218]