Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz | |

|---|---|

Strachwitz in June 1943 | |

| Nickname(s) | Der Panzergraf |

| Born | 30 July 1893 Groß Stein, Province of Silesia, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empirenow Kamień Śląski, Opole Voivodeship, Poland |

| Died | 25 April 1968 (aged 74) Trostberg, Bavaria, West Germany[1] |

| Buried | Cemetery in Grabenstätt |

| Service/ | Prussian Army German Army (1935–1945) |

| Years of service | 1912–45 |

| Rank | Generalleutnant of the Reserves SS-Standartenführer |

| Service number | Nazi Party 1,405,562 SS 82,857 |

| Unit | Guards Cavalry Division Freikorps "von Hülsen" 1st Panzer Division |

| Commands held | Panzer-Regiment "Großdeutschland" of the Grossdeutschland Division |

| Battles/wars | See battles |

| Awards | Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds |

| Other work | land owner and farmer, military advisor |

Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz (also known as Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz von Groß-Zauche und Camminetz) (30 July 1893 – 25 April 1968) was a German officer of aristocratic descent in the Wehrmacht during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds.

Strachwitz was born in 1893 on his family estate in Silesia. He was educated at various Prussian military academies and served in World War I. He was taken prisoner by the French forces in October 1914. He returned to Germany after the war in 1918. He joined the Freikorps and fought against the Spartacist uprising of the German Revolution in Berlin, and in the Silesian Uprisings. In the mid-1920s he took over the family estate from his father and became a member of the Nazi Party and the Allgemeine-SS.

Strachwitz participated in the Invasion of Poland in 1939 and in the Battle of France in 1940. Transferred to the 16th Panzer Division he fought in the Invasion of Yugoslavia and Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, for the Battle of Kalach in the summer of 1942. He received the Swords to his Knight's Cross for his actions in the Third Battle of Kharkov. He then fought in the Battle of Kursk and the German retreat to the Dnieper. While commanding a battle group in the Battle of Narva in early 1944 he was awarded the Diamonds to his Knight's Cross on 15 April. In 1945, he surrendered to US forces and was released in 1947. He died in 1968 and was buried with full military honours.

Early life and career

Strachwitz was born on 30 July 1893 in Groß Stein, in the district of Groß Strehlitz in the Province of Silesia, the Kingdom of Prussia. Today it is Kamień Śląski, in Gogolin, Opole Voivodeship, Poland. Strachwitz was the second child of Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz (1864–1942) and his wife Aloysia (1872–1940),[Note 1] née Gräfin von Matuschka Freiin von Toppolczan und Spaetgen.[4][5][Note 2] He had an older sister, Aloysia (1892–1972), followed by his younger brother Johannes (1896–1917) nicknamed "Ceslaus", his sister Elisabeth (1897–1992), his brother Manfred (1899–1972), his brother Mariano (1902–1922), and his youngest sister Margarethe (1905–1989).[6][7] His family were members of the old Silesian Catholic nobility (Uradel), and held large estates in Upper Silesia, including the family Schloss (castle) at Groß Stein. The family claimed a number of members killed fighting the 1241 Mongol invasion at the Battle of Legnica.[8] As the first-born son he was the heir to the title Graf (Count) Strachwitz, and following family tradition he was christened Hyazinth, after the 12th century saint. Some clothing belonging to the saint were in the family's possession until 1945.[6][9][10]

Strachwitz attended the Volksschule (primary school) and the Gymnasium (advanced secondary school) in Oppeln—present-day Opole. He received further schooling and paramilitary training at the Königlich Preußischen Kadettenkorps (Royal Prussian cadet corps) in Wahlstatt—present-day Legnickie Pole—before he transferred to the Hauptkadettenanstalt (Main Military Academy) in Berlin-Lichterfelde. Among his closest friends at the cadet academy were Manfred von Richthofen, the World War I flying ace and a fellow Silesian, and Hans von Aulock, brother of the World War II colonel Andreas von Aulock.[6][11] In August 1912, Cadet Strachwitz was admitted to the élite Gardes du Corps (Life Guards) cavalry regiment in Potsdam as a Fähnrich (Ensign).[10] The Life Guards had been established by Prussian King Frederick the Great in 1740, and were considered the most prestigious posting in the Imperial German Army. Their patron was Emperor Wilhelm II, who nominally commanded them. Strachwitz was sent to an officer training course at the Kriegsschule (War School) in Hanover in late 1912, where he excelled at various sports.[6][12] Strachwitz was commissioned as Leutnant (Second Lieutenant) on 17 February 1914.[13]

Upon his return to the Prussian Main Military Academy from Hanover, Strachwitz was appointed as the sports officer for the Life Guards. He introduced daily gymnastics and weekly endurance running. The Life Guards sports team was selected to participate in the planned 1916 Olympic Games, and this further encouraged his ambition. He participated in equestrian, fencing and track and field athletics, which became his prime focus. Strachwitz continued to excel as a sportsman, and with his friend Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia, according to Roll Strachwitz was among the best athletes to train for the Olympic Games.[6][14]

World War I

At the outbreak of World War I Strachwitz was mobilized. His regiment was subordinated to the Guards Cavalry Division and scheduled for deployment in the west.[15] His unit arrived at their position near the Belgian border. Strachwitz and his platoon volunteered for a mounted, long-distance reconnaissance patrol, which would penetrate far behind enemy lines. His orders were to gather intelligence on enemy rail and communications connections and potentially disturb them, as well as report on the war preparations being made by the enemy. If the situation allowed, he was to destroy railway and telephone connections and to derail trains, causing as much havoc as possible.[16] His patrol ran into many obstacles and they were constantly on the verge of being detected by either British or French forces. Their objective was the Paris–Limoges–Bordeaux train track. Strachwitz dispatched a messenger, who broke through to the German lines and delivered the intelligence they had gathered. The patrol blew up the signal box at the Fontainebleau railway station,[17] and tried to force their way through to presumed German troops at the Marne near Châlons. However the French forces were too strong and they were unable to get through. After six weeks behind enemy lines their rations were depleted and they had to live by stealing or begging. Strachwitz then intended to head for Switzerland, hoping that the French-Swiss border was not as heavily protected.[18] After a brief skirmish with French forces, one of Strachwitz's men was seriously wounded, which forced them to seek medical attention. During many weeks of outdoor living their uniforms had deteriorated, so Strachwitz took that opportunity to buy new clothes for his men. Their progress was slowed by a wounded comrade, and they were caught in civilian clothes by French forces.[19]

Strachwitz and his men were questioned by a French captain and accused of being spies and saboteurs. They were taken to the prison at Châlons the next day where they were separated. Strachwitz, as an officer, was placed in solitary confinement. Early in the morning they were all lined up for the firing squad, but a French captain arrived just in time to stop the execution. Strachwitz and his men were then tried before a French military court on 14 October 1914. The court sentenced them all to five years of forced labour on the prison island of Cayenne. At the same time they were deprived of rank, thus losing the status of prisoners of war. Strachwitz was then taken to the prisons at Lyon and Montpellier, and then to the Île de Ré, from where the prison ship would depart for Cayenne. It is unclear what circumstances prevented his departure, but he was imprisoned at Riom and Avignon instead. At Avignon prison he was physically and mentally tortured by both the guards and the other prisoners. The torture included being chained naked to a wall, deprived of food and beaten severely. After one year at Avignon he was put in a German uniform and taken to Fort Barraux, used as a prisoner of war facility during the war.[20]

At Barraux he learned that the war in the west had turned into a war of attrition and that only on the Eastern Front were German troops still reporting successes. His health improved rapidly and Strachwitz started making escape plans. With other German soldiers he started digging an escape tunnel, which was detected. Strachwitz was again put in solitary confinement. As a deterrence against German U-boat attacks, German prisoners of war were sometimes carried in the cargo holds of French merchant ships. Now classified as "determined to escape", Strachwitz was put in the cargo hold of a ship which commuted between Marseilles or Toulon and Thessaloniki, Greece. Appearing skeletal after four trips without food, he was returned to Barraux. During further solitary confinement he recovered again, and made further escape plans. With a fellow soldier, he climbed over the prison walls, planning to head for neutral Switzerland. However, Strachwitz injured his foot when he fell into barbed wire, and the injury caused blood poisoning. While searching for help, they were picked up by the French police and turned over to a military court. He was then sent to a war prison for officers at Carcassonne where his request for medical attention was ignored. The injury was severe and he became delirious. An inspection by the Swiss medical commission from the International Red Cross ordered him transferred to a hospital in Geneva, Switzerland, where he awoke after days of unconsciousness.[20]

Strachwitz recovered quickly in Geneva. During his convalescence he was visited by the Queen of Greece, the sister of the German Emperor, Sophia of Prussia, the Duke of Mecklenburg Frederick Francis IV and the Duke of Hesse Ernest Louis. The Archbishop of Munich Michael von Faulhaber, who was on his way to the Vatican, also stopped by to pay his respects. The doctors told Strachwitz that the French government had requested his extradition back to France once he had fully recovered, to serve his full term of five years of forced labour. Strachwitz then moved into a villa in Luzern where he was visited by his mother and sister. He had a great fear of being returned to France, and together they came up with a plan to avoid his extradition. He would "sit out the war" in a mental asylum in Switzerland. The plan worked, though Strachwitz was on the verge of going genuinely mad in the process. The war ended and Strachwitz was released to return to Germany.[21] For his service during the war while imprisoned by the French he was awarded the Iron Cross, Second and First Class.[22]

Interwar period

In the Weimar Republic

After the Armistice in November 1918, Strachwitz was repatriated and returned to a Germany in civil turmoil. He travelled to Berlin via Konstanz, at the Swiss-German border, and Munich. On his journey he saw many former German soldiers whose military discipline had broken down. Unable to tolerate this situation and fearing a Communist revolution, he travelled on to Berlin, arriving at the Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof where he was met by a friend. Strachwitz had called ahead asking his friend to bring him his Gardes du Corps uniform, which he put on immediately. Berlin was in a state of revolution. The newly established provisional government under the leadership of Chancellor Friedrich Ebert was threatened by the Spartacist uprising of the German Revolution, whose ambition was a Soviet-style proletarian dictatorship. Ebert ordered the former soldiers, organized in Freikorps (paramilitary organizations) among them Strachwitz, to attack the insurgents and put down the uprising.[22]

In early 1919, following these events in Berlin, Strachwitz returned to his home estate, where he found his family palace taken over by French officers. Upper Silesia was occupied by British, French and Italian forces, and being governed by an Inter-Allied Committee headed by a French general, Henri Le Rond. The Versailles Treaty at the end of World War I had shifted formerly German territory into neighbouring countries, some of which had not existed at the beginning of the war. In the case of the new Second Polish Republic, the Treaty detached some 54,000 square kilometres (21,000 sq mi) of territory, which had formerly been part of the German Empire, to recreate the country of Poland, which had disappeared as a result of the Third Partition of Poland in 1795.[23] His father urged him to prepare and educate himself in order to take over the family estate and business. He was put under the guidance of his father's Oberinspektor (Chief Inspector). In parallel, Strachwitz, fearing that Silesia was being "handed over to the Poles", as he viewed the actions of the Inter-Allied Committee, joined the Oberschlesischer Selbstschutz (Upper Silesian Self Defence). Strachwitz collected weapons and recruited volunteers, which was prohibited. He was caught four times and put in prison in Oppeln by the French. Also his father had to go to prison for his opposition to the Inter-Allied Committee. His distrust for the French, rooted in his experiences as a prisoner of war during World War I, was immense. He believed that only the Italians had played an honest and neutral role in the occupation of Upper Silesia. On 25 July 1919, he married Alexandrine Freiin Saurma-Jeltsch, nicknamed "Alda", and their first child, a son, was born on 4 May 1920.[24]

In 1921, during the Silesian Uprisings, when Poland tried to separate Upper Silesia from the Weimar Republic, Strachwitz served under the Generals Bernhard von Hülsen and Karl Höfer. At the peak of the conflict when the Poles dug in on the Annaberg, a hill near the village of Annaberg—present-day Góra Świętej Anny. The German Freikorps launched the assault in what would become the Battle of Annaberg, which was fought between 21 May and 26 May 1921. Strachwitz and his two battalions outflanked the Polish positions and overran part of them in hand-to-hand combat around midnight on 21 May. Strachwitz was the first German to reach the summit. They captured six field guns, numerous machine guns, rifles and ammunition.[26] On 4 June the Freikorps attacked Polish positions at Kandrzin—present-day Kędzierzyn—and Slawentzitz—present-day Sławięcice. In this battle Strachwitz and his men captured a Polish artillery battery which they turned against the Poles.[26] For these services he received the Schlesischer Adler (Silesian Eagle) medal, Second and First Class with Oak Leaves and Swords. His younger brother Manfred also fought for Silesia, and was severely wounded leading his men at Krizova. Two months later his wife gave birth to their second child, a daughter named Alexandrine Aloysia Maria Elisabeth Therese born on 30 July 1921, nicknamed "Lisalex". The Ministry of the Reichswehr informed him in 1921 that he had been promoted to Oberleutnant (first lieutenant), the promotion backdated to 1916. The Strachwitz family grew further when on 22 March 1925 a third child, a son named Hubertus Arthur, nicknamed "Harti", was born on their manor at Schedlitz, later renamed Alt Siedel—present-day Siedlec.[27]

In 1925, Strachwitz and his family moved from Groß Stein to their manor in Alt Siedel, because of personal differences with his father, who remained in Groß Stein. Between 1924 and 1933 Strachwitz founded two dairy cooperatives which many local farmers joined. In parallel he studied a few semesters of forestry. He used his influence in Upper Silesia to modernize forestry and farming. His ambitions were aided by his presidency of the Forstausschuss (Forestry Committee) of Upper Silesia and his membership in the Landwirtschaftskammer (Chamber of Agriculture).[27] Strachwitz completely took over his father's estate in 1929, first as the general manager and then as owner. This made Strachwitz one of the most wealthy land and forest owners in Silesia. Along with the palace in Groß Stein he owned a lime kiln and quarry in Klein Stein—present-day Kamionek—and Groß Stein, a distillery in Groß Stein and Alt Siedel.[28]

National Socialism

Strachwitz applied for membership in the Nazi Party with the Reichsleitung (Reich Leadership) of the Nazi Party in Munich in 1931. He was accepted and in 1932 joined the Ortsgruppe (Local Group) of the party in Breslau with a membership number 1,405,562. On 17 April 1933 he became a member of the Allgemeine-SS with the SS membership number 82,857, and reached the rank of SS-Sturmbannführer in 1936. In parallel to his SS career, his military rank in the military reserve force also advanced. He attained the rank of Hauptmann of the Reserves in 1934 and a year later became a Rittmeister (cavalry captain) of the Reserves.[28]

On 30 January 1933, the Nazi Party, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, came to power and began to rearm Germany. The Germany Army was increased and modernized with a strong focus on the Panzer (tank) force. Personnel were recruited from the cavalry. In October 1935 Panzer Regiment 2 was created and was subordinated to the 1st Panzer Division, at the time under command of General Maximilian von Weichs. Strachwitz, who had served as an officer of the reserves in the 7th Cavalry Regiment in Breslau, had asked to be transferred to the Panzer force and, in May 1936 and then from July to August 1937, Strachwitz was involved in manoeuvres and training exercises.[28] The 1st Panzer Division was moved to Silesia in preparation for the invasion of Poland on 25 August 1939.[29]

World War II

Panzer-Regiment 2, as part of the 1st Panzer Division, consisted of four light companies and two medium companies totaling 54 Panzer Is, 62 Panzer IIs, 6 Panzer IIIs, 28 Panzer IVs and 6 command tanks. The Wehrmacht invaded Poland without a formal declaration of war on 1 September 1939, and Strachwitz's regiment crossed the border that day. In early October the division was transferred back to Germany; Strachwitz returned to his regiment in late 1939.[30]

Battle of France

The 1st Panzer Division was preparing for the attack on France and the Low Countries, with Strachwitz serving as a supply officer in the 2nd Panzer Regiment. He was out sick with meningitis and in a hospital from 1–9 March 1940, and then from 28 April – 9 May 1940 with an injured foot. The division was subordinated to XIX Army Corps under the command of General Heinz Guderian.[31] The German attack, under the Fall Gelb directive, began on the morning of 10 May 1940. The XIX Army Corps advanced without resistance through Luxemburg and reached the Belgian border at 10:00.[32] During the crossing of the Meuse, the first objective, Strachwitz organized the traffic across the bridge and ensured delivery of the anti-aircraft ammunition to help fend off an Allied aerial attack. The French resistance was broken near Vendresse.[33]

The 1st Panzer Division continued to push forward, reaching the Channel coast near Calais on 23 May 1940, where they encountered heavy British resistance. The 10th Panzer Division was tasked with taking Calais, while Guderian ordered the 1st Panzer Division to head for Gravelines.[34] Elements of the 1st Panzer Brigade and the subordinated Infantry Regiment (motorized) Großdeutschland reached the river Aa south of Gravelines that night, 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) southwest of Dunkirk. Strachwitz went on one of his "solo runs", penetrated the French and British lines and almost reached Dunkirk, where he observed the evacuation of British and allied forces by sea, which he reported to his commanding officer and the divisional staff.[35]

Parts of the 1st Panzer Division were relocated to Rethel on 2 June. The second phase of the Battle of France, Fall Rot (Case Red), was about to begin and Strachwitz returned to the 2nd Panzer Regiment where he again served as a supply officer. Strachwitz in the meantime had been awarded the Clasp to the Iron Cross 1st Class on 6 June for his daring "solo runs". The two regiments of the 1st Panzer Division crossed the Aisne on the night of 9/10 June 1940. The final objective was Belfort, which capitulated after a short resistance. This ended the Battle of France for Strachwitz's regiment.[35] After having detached two Panzer companies for Operation Sea Lion, the planned and aborted invasion of the United Kingdom, the remaining units of the 2nd Panzer Regiment were transferred to East Prussia.[36]

Balkans campaign

On 2 October 1940, following the Battle of France, Panzer Regiment 2 was subordinated to the 16th Panzer Division. Strachwitz asked the divisional commander Generalmajor Hans Hube for the command of a Panzer company, and Hube gave Strachwitz the 1st Battalion, a position he held until October 1942.[37] In December 1940, 16th Panzer Division was declared a Lehrtruppe (demonstration troop), a unit to be involved in experimentation with new weapons and tactics. Via Bavaria, Austria and Hungary they were transferred to Romania, with Strachwitz's I. Battalion stationed at Mediaș.[36]

The division was tasked with the protection of the oil fields at Ploiești, which were vital to the German war effort. They trained some Romanian officers in German Panzer tactics. Apart from training, the soldiers had nothing to do and became bored. In March 1941 Strachwitz was sent back to Cosel in Germany where a new replacement unit was to be founded. He returned via his home town and 24 hours later a telegram from Hube called him back. This was preceded by a series of events in Belgrade. On 25 March 1941, the government of Prince Paul of Yugoslavia had signed the Tripartite Pact, joining the Axis powers in an effort to stay out of World War II. This was immediately followed by mass protests in Belgrade and a military coup d'état led by Air Force commander General Dušan Simović. As a result, Hitler chose not only to support Mussolini's ambitions in Albania and in the Greco-Italian War but also to attack Yugoslavia. For this purpose the mobilized forces of 1st Panzer Group under the command of Generaloberst Ewald von Kleist were ordered to attack Belgrade in what would become the Invasion of Yugoslavia.[36]

Strachwitz's 1st Battalion received the order to prepare for the attack on 6 April 1941. His orders were to break through with the Infanterie-Regiment (motorized) "Großdeutschland" to Belgrade via Werschetz—present-day Vršac. His right flank was protected by the SS-Division "Das Reich" and his left flank by the 11th Panzer Division.[36] The attack was preceded by a heavy artillery barrage and the Germans crossed the border at 10:30. The defences were quickly taken and the German troops reached the Werschetz where they were greeted by cheering inhabitants and a band. Their next objective was the River Danube. They reached the Danube at Pančevo only to find the bridge there destroyed. At Pančevo Strachwitz's unit linked up with the 11th Panzer Division. Here he encountered his oldest son Hyazinth, who was serving with the 11th Panzer Division. Strachwitz started confiscating boats and barges in an attempt to cross the Danube. This work had begun when Strachwitz received the order to halt all activities. His unit was ordered to retreat to Timișoara. On 16 April Hube announced that the 16th Panzer Division would no longer be needed in the campaign and were ordered to regroup at Plovdiv. In early May 1941 Oberstleutnant Rudolf Sieckenius was given command of Panzer-Regiment 2. The entire 16th Panzer Division was ordered back to their home bases in Germany, with Panzer-Regiment 2 ordered to Ratibor—present-day Racibórz, where their equipment was overhauled. Strachwitz was awarded the Coroana României on 9 June 1941.[38]

In mid-June 1941, the division received new orders to relocate. The 16th Panzer Division crossed the German-Polish border at Groß Wartenberg—present-day Syców, heading for Ożarów at the Vistula, which was reached on 19 June 1941. The German soldiers initially believed that they were just going to transit through Russia, on their way to the Middle East where they would link up with Erwin Rommel's Afrika Corps. But Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Walther von Reichenau, who visited his son, a Leutnant in the 4th company of Panzer-Regiment 2, revealed to them the true objective of the next campaign. It would be Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.[38]

War against the Soviet Union

The German offensive began at 3:30 on 22 June 1941 with an artillery strike against the Soviet Union. The 16th Panzer Division was subordinated to Army Group South under the command of Field Marshal von Rundstedt. The goal, together with the 6th Army and 17th Army as well as Panzer Group 1, was to follow the pincers of both armies, heading for Kiev and rolling up the Soviet flanks in the process, and encircling them at the Dnieper River. The main objective was to occupy the economically important Donets Basin as well as the oil field in the Caucasus.[39]

German Army reconnaissance aircraft spotted the first enemy formations in the vicinity of the 16th Panzer Division on the morning of 26 June. By this date the division had already progressed 125 kilometres (78 mi) beyond the German-Soviet demarcation line and secured a bridgehead over the Bug River. Supplies were lagging behind and not before 28 June was his regiment resupplied. His unit first encountered the T-34 and a few KV-1 and KV-2 tanks the following day. These tanks had stronger armour and outgunned his Panzer III tanks. With the support of the 88 mm Flak artillery, deployed in an anti tank role, they were able to repulse the Soviet forces.[40] The brigade crossed the Dnieper on the night of 11/12 September. Following the encirclement of Soviet forces in the Battle of Kiev the brigade was dispatched to prevent Soviet troops from escaping the pocket. The brigade remained in action until 4 October 1941.[41]

Strachwitz was promoted to Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) of the Reserves on 1 January 1942. He returned to the Eastern Front in mid-March 1942.[42] Throughout the summer of 1942 Strachwitz led his tanks in the advance to the Don River and across it to Stalingrad.[43] His unit was the first to reach the Volga River north of Stalingrad on 23 August 1942.[44] By this time the 16th Panzer Division was assigned to the 6th Army, which was encircled at Stalingrad in November 1942. By now, Strachwitz had been promoted to command the Panzer-Regiment.[43]

Strachwitz was severely wounded on 13 October 1942, requiring immediate treatment in a field hospital. A direct hit on his command tank caused severe burns. Strachwitz handed over command of his I./Panzer-Regiment 2 to Hauptmann Bernd Freytag von Loringhoven.[45] He then had to be flown out and was treated at a hospital at Breslau until 10 November 1942. He received further treatment at the Charité in Berlin from 11 to 18 November 1942. During this stay he received news that he had been awarded the Oak Leaves to his Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. He was ordered to the Führerhauptquartier in December 1942 for the presentation of the Oak Leaves by Hitler himself. He then went to Bad Gastein for a period of convalescence before spending his vacation at home in Alt Siedel. Strachwitz was promoted to Oberst (colonel) of the Reserves on 1 January 1943.[46]

Großdeutschland Panzer-Regiment

At the end of January 1943 Strachwitz was ordered to the Führerhauptquartier. Talking to General Rudolf Schmundt and Kurt Zeitzler, the Chief of Staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres, he was tasked with the creation of the Panzer-Regiment "Großdeutschland". The regiment was subordinated to the Infanterie-Division (motorized) "Großdeutschland" then under the command of Generalmajor Walter Hörnlein.[47] Strachwitz was officially placed in command of the regiment on 15 January, arriving with this unit in late February at Poltava. According to Tewes, this assignment intended to increase the combat effectiveness of the "Großdeutschland" division. Hörnlein had little experience with tank warfare and needed an experienced tank commander as an advisor.[48] He led the regiment when it took part in the Third Battle of Kharkov, fighting alongside SS-Gruppenführer Paul Hausser's II SS Panzer Corps.[49] Strachwitz was awarded the Swords to his Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves on 28 March 1943. He received the latter for his leadership at Kharkov and Belgorod.[50][51]

On 5 July 1943, the first day of Operation Citadel (5–16 July 1943), the German code name for the Battle of Kursk, in the Großdeutschland area of operations, the Panther battalion got bogged down in the mud near Beresowyj and failed to support the Füsilier's attack. Nipe indicates that often Oberst Karl Decker and Oberstleutnant Meinrad von Lauchert have been made responsible for this failure. However, Nipe argues "that it can safely be assumed that Strachwitz was present; thus, any responsibility regarding actions of Großdeutschland's Panzers belongs to the Panzer Count."[52] Following the battle, Decker wrote a letter to Guderian complaining about the unnecessary losses infringed by the Großdeutschland division. In this letter Decker stated, that how Strachwitz lead his tanks on the first day of Kursk must be characterized as "idiotic".[53]

Strachwitz was wounded again on 10 July. His battle group had been ordered into combat by Hörnlein. The objective was to capture Hill 258.4, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) west of Werchopenje. The battle group encountered roughly 30 Soviet tanks on evening of 9 July. An attack proved unfeasible due to the settling darkness. During these events he received news that his son, Hyazinth, had been severely wounded. At dusk on 10 July he ordered the attack on the Soviet tanks. The first T-34s had been destroyed and Strachwitz was directing the attack from his command tank and had ordered his gunner to hold fire. Strachwitz was carelessly resting his left arm on the gun-breech. The gunner, without orders, fired the gun, causing the recoiling gun to smash his left arm. Strachwitz was immediately evacuated to a field hospital.[54] In consequence, Strachwitz passed command of the battle group to Hauptmann Walter von Wietersheim.[55] Strachwitz's arm was put in a cast and against medical advice returned to his regiment. When Hörnlein learned of this he went furious and gave Strachwitz a direct order to return to the field hospital.[56] In November 1943, Strachwitz left the "Großdeutschland".[57]

Battle for the Krivasoo Bridgehead

The severe injury to Strachwitz's left arm had forced him to retire from the front line.[57] After a stay in the hospital at Breslau and a period of convalescence at home he received an order assigning him as "Höheren Panzerführer" (higher tank commander) to the Army Group North. Strachwitz reported to the commander-in-chief of the 18th Army, Generaloberst Georg Lindemann, commander of Army Group North.[58]

On 26 March 1944, the Strachwitz Battle Group consisting of the German 170th, 11th, and 227th Infantry Divisions and a tank hunting brigade, attacked the flanks of the Soviet 109th Rifle Corps south of the Tallinn railway, supported by an air strike. The tanks led the attack and the infantry followed, penetrating the fortified positions of a Soviet rifle corps. By the end of the day, the Soviet 72nd and parts of the 109th Rifle Corps in the Westsack (west sack) of the bridgehead were encircled. The rest of the Soviet rifle corps retreated, shooting the local civilians who had been used for carrying ammunition and supplies from the rear.[59]

As Strachwitz had predicted, the rifle corps counterattacked on the following day. It was repelled by the 23rd East Prussian Grenadier Regiment which inflicted heavy casualties on the Soviets. Two small groups of tanks broke through the lines of the rifle corps on 28 March in several places, splitting the bridgehead in two. Fierce air combat followed, with 41 German dive bombers shot down. The west half of the bridgehead was destroyed by 31 March, with an estimated 6,000 Soviet casualties.[60] On April 1, 1944, Strachwitz was promoted to Generalmajor (Major General) of the Reserves.[61]

The Ostsack (east sack) of the Krivasoo bridgehead, defended by the Soviet 6th and the 117th Rifle Corps, were confused by the Strachwitz Battle Group's diversionary attack on 6 April. The attack deceived the Soviet forces into thinking that the German attack intended to cut them out from the west flank. The actual assault came directly at the 59th Army and started with a heavy bombardment. The positions of the 59th Army were attacked by dive bombers and the forest there was set afire. At the same time, the 61st Infantry Division and the Strachwitz tank squadron pierced deep into the 59th Army's defences, splitting the two rifle corps apart and forcing them to retreat to their fortifications. Marshal of the Soviet Union Leonid Govorov was outraged by the news, sending in the freshly re-deployed 8th Army. Their attempt to cut off the Tiger I tanks was repelled. On 7 April, Govorov ordered his troops to switch on to the defensive. The 59th Army, having lost another 5,700 troops from all causes, was withdrawn from the bridgehead. For these successes Strachwitz received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds on 15 April 1944.[62] The official presentation was made a few weeks later by Hitler.[63]

The spring thaw meant that the tanks were then impossible to use. The 8th Army repelled the German attack, which lasted from 19 to 24 April. The Germans lost 2,235 troops, dead and captured, in the offensive, while the total of German casualties in April, from all causes, was 13,274. Soviet casualties in April are unknown, but are estimated by Mart Laar to be at least 30,000 men from all causes. The losses exhausted the strengths of both sides. The front subsequently stagnated with the exception of artillery, air, and sniper activity and clashes between reconnaissance platoons for the next several months.[64]

Final battles

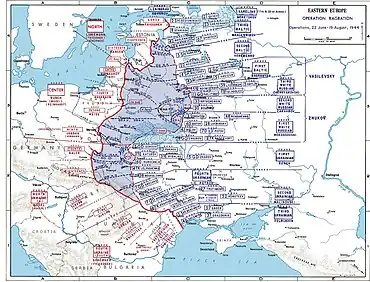

Strachwitz led an ad-hoc formation in Operation Doppelkopf as part of Dietrich von Saucken's XXXIX Panzer Corps counter-offensive following the major Soviet advance in Operation Bagration. Saucken's goal was to relieve the encircled forces in the Courland Pocket. Strachwitz's attack on 18 August was preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment from the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen; forces inside the pocket attacked to link up with Strachwitz's force. His troops reached the 16th Army at Tukums by midday.[65]

During a visit to a division command post on 24 August 1944 Strachwitz was badly injured in an automobile accident. The vehicle rolled over and the other occupants were killed. He sustained a fractured skull and other injuries, and his survival was in doubt. He was treated at a field hospital, and then at Riga and Breslau.[66] Strachwitz signed himself out of the hospital and convalesced at his manor in Alt Siedel from 28 November to 23 December 1944.[66]

The Red Army started the Vistula–Oder Offensive on 12 January 1945. Within a matter of days the Soviet forces had advanced hundreds of kilometres, taking much of Poland and striking deep within the borders of the Reich. The offensive broke Army Group A and much of Germany's remaining capacity for military resistance. The Soviet forces crossed the Silesian border on 19 January and Generaloberst Ferdinand Schörner was appointed commander of the army group on 20 January.[67] At Schörner's headquarters at Oppeln, Strachwitz requested a frontline command. Schörner initially assigned him to his staff where Strachwitz developed a proposal that would create a specialized Panzerjagdbrigade (tank-hunting brigade).[68] The 3rd Guards Tank Army occupied Oppeln and Groß Stein on 23 and 24 January 1945, respectively.[69] Schörner authorized the creation of tank destroyer brigade. These brigades were not mechanized units but rather infantry soldiers deploying hand-held weapons such as the Panzerfaust.[70] On 30 January 1945, he was promoted to Generalleutnant of the Reserves and put in command of the newly created Panzerjäger Brigade Upper Silesia.[71]

Strachwitz's command received about 8,000 recruits, mostly from the threatened territories of Pomerania, East Prussia and Silesia. Strachwitz' tactics quickly made news within the Wehrmacht.[70] Strachwitz then became commander of the Panzerjagdverbände of Army Group Vistula, and, in April, of the Panzerjagdeinheiten of Army Group Centre. Strachwitz and his men fought under the command of Schörner until the German capitulation on 8 May 1945.[70] Strachwitz surrendered to the US Army in Bavaria. He was taken to the prisoner of war camp at Allendorf near Marburg, where he was interned together with former Wehrmacht generals Franz Halder, Heinz Guderian and Adolf Galland.[72]

Involvement with the German resistance

According to the historian Steinbach, Strachwitz was in contact with the German military resistance to Nazism.[73] Hoffmann states, with Generals Hubert Lanz, Hans Speidel and Paul Loehning, he is shown as being associated with "Plan Lanz", as testified by General der Gebirgstruppe Hubert Lanz. The plan was to arrest or kill Hitler in early February 1943 during Hitler's scheduled visit to Army Detachment Lanz at Poltava. In this account, Strachwitz's role was to surround Hitler and his escorts shortly after Hitler's arrival with his tanks. Lanz stated that he would have then arrested Hitler, and in the event of resistance, Strachwitz's tanks would have shot and killed the entire delegation. Hitler cancelled the visit and the plan was dropped.[74] In addition, Tewes states that this plan was discussed by Lanz and Strachwitz at Valky. The idea was to arrest and hand over Hitler into the custody of Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge, at the time commander-in-chief of Army Group Centre.[10]

Author Röll however casts doubt on this account citing that Strachwitz's cousin, Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff, who attempted to assassinate Hitler in 1943, had recounted that Strachwitz had expressed the belief to him several times that killing Hitler would have constituted murder. Röll concludes that Strachwitz was too much a Prussian officer to consider assassinating Hitler.[75]

After World War II and final years

Strachwitz was released by the Allies in June 1947. By the time of his release, he had lost his wife, his youngest son and his estate. Alda was killed in a traffic accident on 6 January 1946, run over by a US military truck in Velden an der Vils. Strachwitz, still a US prisoner of war in camp Allendorf near Marburg, was denied permission to attend the funeral.[72] Harti, who had lost a leg, was killed in action shortly before the end of the war on 25 March 1945 near Holstein. Strachwitz married Nora von Strumm (1916–2000), granddaughter of Baron Ferdinand Eduard von Stumm, on 30 July 1947 in Holzhausen. He and Nora had four children, two daughters and two sons, born between 1951 and 1960.[76]

At the invitation of Husni al-Za'im, Strachwitz was in Syria acting as an agricultural and military advisor for the Syrian Armed Forces from January–June 1949 during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[77] The influential man behind Husni al-Za'im was Adib Shishakli, who wanted a Pan-Arabian revolution and was trying to run the state from behind the scenes. Seeing himself as a state-maker, the Otto von Bismarck of the Arabian peoples, Shishakli's goal was to transform Syria into a kind of "Prussian Arabia". Under his leadership, Syria brought over 30 advisors to Syria. Strachwitz, bragging about his military successes in Russia, had a very difficult time with the Syrian officers, and his agricultural suggestions were ignored as well. When Adib Shishakli seized power, Strachwitz and his wife left Syria. In the meantime, they had received a visa for Argentina, where they hoped to find another advisory position. Via Lebanon, they arrived in Livorno, Italy, where they changed their plans and ran a winery. They returned to Germany in 1951 with a Red Cross passport. He settled on an estate in Winkl near Grabenstätt in Bavaria and founded the "Oberschlesisches Hilfswerk" (Upper Silesian Fund) supporting fellow Silesians in need.[76]

Strachwitz died on 25 April 1968 of lung cancer in hospital in Trostberg. He was laid to rest in the village cemetery of Grabenstätt, beside his first wife.[78] The Bundeswehr provided an honour guard as a mark of respect. Heinz-Georg Lemm delivered the eulogy.[79]

Awards

- Iron Cross (1914)

- Silesian Eagle 2nd and 1st Class with Oak Leaves and Swords (1921)[61]

- Clasp to the Iron Cross (1939)

- Order of the Crown (Romania) (9 June 1941)[38]

- Panzer Badge

- Eastern Front Medal (August 1942)[61]

- Wound Badge (1939)

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

- Knight's Cross on 25 August 1941 as Major of the Reserves and commander of the I./Panzer-Regiment 2[82][83]

- 144th Oak Leaves on 13 November 1942 as Oberstleutnant of the Reserves and commander of the I./Panzer-Regiment 2[82][84]

- 27th Swords on 28 March 1943 as Oberst of the Reserves and commander of the Panzer-Regiment "Großdeutschland"[82][85]

- 11th Diamonds on 15 April 1944 as Oberst of the Reserves and commander of a Panzer-Gruppe with the Heeresgruppe Nord[82][86]

- Units under his command have been mentioned numerous times in the Wehrmachtbericht[61]

Notes

- ↑ Her full name was Maria Aloysia Hedwig Friederike Therese Oktavie, Gräfin von Matuschka, Freiin von Toppolczan und Spaetgen.[2][3]

- ↑ Regarding personal names: Freiin was a title before 1919, but now is regarded as part of the surname. It is translated as Baroness. Before the August 1919 abolition of nobility as a legal class, titles preceded the full name when given (Graf Helmuth James von Moltke). Since 1919, these titles, along with any nobiliary prefix (von, zu, etc.), can be used, but are regarded as a dependent part of the surname, and thus come after any given names (Helmuth James Graf von Moltke). Titles and all dependent parts of surnames are ignored in alphabetical sorting. The title is for unmarried daughters of a Freiherr.

References

Citations

- ↑ Von Ehrenkrook 2000, p. 497.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, p. 14.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 13, 16.

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Röll 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, p. 15.

- ↑ Perrett, B. Iron Fist Classic Armoured Warfare Studies 1999 p.172 ISBN 1860199542

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 3 Tewes 2020, p. 295.

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, p. 21.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 188.

- ↑ Bagdonas 2013, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 14.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 20–22.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 30.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 31.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 32.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 48.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 43.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Röll 2011, p. 49.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 50, 187.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 51, 189.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 52.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 53.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 54.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 Röll 2011, p. 70.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 70, 188.

- 1 2 3 Röll 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 93.

- 1 2 Williamson 2006, p. 26.

- ↑ Beevor 1999, pp. 104–108.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 109.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 110.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Tewes 2020, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 114.

- ↑ Tewes 2020, p. 314.

- ↑ Nipe 2011, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Nipe 2011, p. 447.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 135.

- ↑ Tewes 2020, p. 1158.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 136.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 138.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 139.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 140.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 140–142.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Röll 2011, p. 189.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 148.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 152.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 167–170.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 171.

- ↑ Röll 2011, p. 172.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 173–174.

- 1 2 3 Röll 2011, p. 174.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 174, 189.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 175.

- ↑ Steinbach 1999, pp. 1150–1170.

- ↑ Hoffmann 1985, pp. 348–350.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 184–186.

- 1 2 Röll 2011, p. 176.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 176, 188.

- ↑ Hartmann 2000, p. 160.

- ↑ Röll 2011, pp. 176, 181.

- 1 2 Thomas 1998, p. 356.

- 1 2 Federl 2000, p. 284.

- 1 2 3 4 Scherzer 2007, p. 728.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 413.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 63.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 37.

Bibliography

- Bagdonas, Raymond (2013). The Devil's General: The Life of Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz – the "Panzer Graf". Philadelphia; Oxford: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-222-4. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Beevor, Antony (1999). Stalingrad. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-024985-9.

- Von Ehrenkrook, Hans Friedrich (2000). Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Gräfliche Häuser Band XVI. Band 123 der Gesamtreihe (in German). Limburg (Lahn), Germany: C. A. Starke Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7980-0823-6.

- Federl, Christian (2000). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Deutschen Panzerdivisionen 1939–1945 Die Panzertruppe (in German). Zweibrücken, Germany: VDM Heinz Nickel. ISBN 978-3-925480-43-0.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer [in German] (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Hartmann, Wolfgang (2000). Breslauer Passion 1945–1947: Festschrift zum 70. Geburtstag des schlesischen Heimatforschers Horst G.W. Gleiss am 26. August 2000 (in German). Natura et Patria Verlag. ISBN 978-3-921060-06-3. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- Hoffmann, Peter (1985). Widerstand – Staatsstreich – Attentat. Der Kampf der Opposition gegen Hitler [Resistance, Coup d'etat, Assassination — The Battle of the Opposition against Hitler] (in German). München, Germany: Piper. ISBN 978-3-492-00718-4.

- Meyer, Hermann Frank (2008). Blutiges Edelweiß: Die 1. Gebirgs-Division im Zweiten Weltkrieg [Bloody Edelweiss: The 1st Mountain Division in World War II] (in German). Berlin, Germany: Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-447-1.

- Nipe, George M. (2011). Blood, Steel and Myth—The II. SS-Panzer-Korps and the road to Prochorowka, July 1943. Stamford, CT: RZM Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9748389-4-6.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941 – 1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941 – 1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Röll, Hans-Joachim (2011). Generalleutnant der Reserve Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz von Groß-Zauche und Camminetz: Vom Kavallerieoffizier zum Führer gepanzerter Verbände [Lieutenant General of the Reserve Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz von Groß-Zauche und Camminetz: From a Cavalry Officer to a Leader of Armoured Units] (in German). Würzburg, Germany: Flechsig. ISBN 978-3-8035-0015-1.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Miltaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Steinbach, Peter (1999). Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Volkmann, Hans-Erich (eds.). Die Wehrmacht: Mythos und Realität [The Wehrmacht: Myth and Reality] (in German). Munich, Germany: Military History Research Office. ISBN 978-3-486-56383-2.

- Thomas, Franz (1998). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 2: L–Z [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 2: L–Z] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2300-9.

- Tewes, Ludger [in German] (2020). Die Panzergrenadierdivision Großdeutschland im Feldzug gegen die Sowjetunion 1942 bis 1945 [The Panzergrenadierdivision Großdeutschland in the campaign against the Soviet Union from 1942 to 1945] (in German). Essen, Germany: Klartext. ISBN 978-3-8375-2089-7.

- Williamson, Gordon (2006). Knight's Cross with Diamonds Recipients 1941–45. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-644-7.

External links

- Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz in the German National Library catalogue

- "Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz". Der Spiegel (in German). 1949. Retrieved 10 February 2013.