Zinc mining in the United States produced 780,000 tonnes (860,000 short tons) of zinc in 2019, making it the world's fourth-largest zinc producer, after China, Australia, and Peru. Most US zinc came from the Red Dog mine in Alaska. The industry employed about 2,500 in mining and milling, and 250 in smelting.[1]

Current zinc-mining districts

In 2019 zinc was mined in six States at 15 mines operated by five companies.[1]

Red Dog Mine, Alaska

In 2019, 552,400 tonnes of zinc, 71 percent of US mined zinc production, and 4.2 percent of world zinc production, came from Teck Resources' Red Dog mine, the world's most productive zinc mine, in northwest Alaska, near Kotzebue.[2][3][1] The mine opened in 1989.[4] The zinc is shipped as concentrate to foreign smelters. The Red Dog is a polymetallic deposit, which also produces lead and silver concentrates.[5]

Admiralty Island, Alaska

Hecla Mining's Greens Creek mine located 17 mi (27 km) south-southwest of Juneau, Alaska, on Admiralty Island, opened in August 1989. The mine produces silver, gold, zinc and lead from a structurally and mineralogically complex VMS deposit. In 2019 it produced 56,805 tonnes of zinc in concentrate as a byproduct of silver-gold mining.[6]

Coeur D'Alene district, Idaho

At the Coeur D'Alene mining district in northern Idaho, zinc is produced as a byproduct of silver mining in Hecla Mining's Lucky Friday mine. In 2019 the mine produced 2,052 tonnes of zinc in concentrate.[7]

Viburnum Trend, Missouri

Doe Run Resources' mines on carbonate-hosted lead-zinc deposits (Mississippi Valley-type deposits) in the Southeast Missouri Lead District include Casteel, Buick, Brushy Creek, Fletcher, Sweetwater and Mine No. 29.

Middle and East Tennessee Zinc Complexes, Tennessee

In the Middle and East Tennessee Zinc Complexes, Nyrstar's six mines produce zinc from carbonate-hosted lead-zinc deposits. They are the Coy, Immel, and Young mines in the East Tennessee Zinc Complex, and the Gordonsville, Elmwood, and Cumberland mines in the Middle Tennessee Zinc Complex. Nyrstar produced 115,000 tonnes of zinc in concentrate from its East and Middle Tennessee mines in 2018.[8]

Metaline district, Washington

In July 2019 Teck Resources' Pend Oreille mine in Washington's Metaline mining district ceased production due to exhaustion of reserves.[1]

Former zinc-mining districts

Tri-state district

The Tri-State district of Missouri, Oklahoma and Kansas was the major zinc mining district in the United States, with production of 10.6 million tonnes of zinc from c.1850 through 1967. The Eagle-Picher mine of Cardin, Oklahoma, the largest and longest lived mine, ceased production in 1967.[9]

Franklin mining district, New Jersey

The Franklin and Sterling Hill deposits with production of 6.3 million tonnes of zinc, account for 15 percent of all recorded zinc production in the contiguous United States. Major mining began about 1870, and the Sterling Hill mine was the last working underground mine in New Jersey when it closed in 1986.[9][10]

Southeast Missouri lead district

Zinc was produced as a byproduct of lead mining in the Southeast Missouri Lead District.

Austinville-Ivanhoe district, Virginia

Mining operations began in 1756 in the Austinville-Ivanhoe District of Wythe County, Virginia. By the time the mine closed in 1981, it was the most continuously mined base metal deposit in North America, with a total production of 1.4 million tonnes of zinc.[11]

Smelting

The US has two smelter facilities, one primary and one secondary, producing commercial-grade zinc metal.

Primary smelters produce metal from ore. The only US primary zinc smelter, the Nyrstar smelter at Clarksville, Tennessee, produced 120 tonnes of zinc, from a mix of ore from six mines in middle and east Tennessee, and recycled zinc products.

Secondary zinc smelters produce zinc from recycled materials. A secondary zinc smelter in Pennsylvania closed in 2014, the operations being shifted to a new smelter in North Carolina using solvent extraction/electrowinning (SXEW). In addition, some non-smelting zinc recycling operations produced small amounts of zinc. The total amount of zinc produced from secondary operations was 70 tons. For primary and secondary smelters taken together, recycled products accounted for 25 percent (30,000 tonnes) of the refined zinc produced in US in 2019.[12][1]

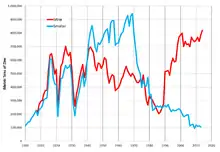

Through 1940, the production of primary zinc by US smelters approximated the mined production of zinc ore. When zinc demand increased during World War II, US smelters turned to foreign zinc ore. US-smelted zinc reached a high of 926,000 tonnes in 1970, then dropped as smelters closed. There were 12 primary zinc smelters in 1970, but only seven in 1980, three in 1990, and two in 2000. Today, there is one operating primary zinc smelter, in Clarksville, Tennessee, which produces zinc from mines in the East Tennessee and Middle Tennessee districts. All other zinc concentrates are exported and smelted abroad.

Byproducts of zinc

A number of elements are recovered in flue gas and flue dust in zinc smelters. These include the metal cadmium and the semi-metals gallium and germanium. In 1970, for every ton of zinc produced at a US smelter, there were also recovered 4.2 kilograms of cadmium, 53 grams of germanium, 18 grams of indium, and 2.9 grams of thallium.[13] These elements are concentrated as impurities in the zinc mineral sphalerite. The elements are more abundant in sphalerite from ore deposits with lower formation temperatures, such as Mississippi Valley-type deposits. The Middle and East Tennessee zinc mines are Mississippi Valley-type.

Cadmium recovered in zinc smelting is the only commercial source of cadmium. Gallium and germanium are also recovered some from other sulfide ores. Some germanium is also recovered from aluminum smelting. In previous years, indium and thallium were recovered from zinc smelting, but as of 2015, they were not being recovered from American zinc smelters.

According to the British Geological Survey, in 2011, US zinc smelting recovered about 600 tonnes of cadmium, three tonnes of gallium, and three tonnes of germanium.[14]

Consumption

In 2019, the US consumed 950,000 tons of zinc. Most zinc is used for galvanizing, followed by brass and bronze, and zinc-based alloys.[1]

International trade

The United States is a net importer of zinc (87% of consumption). In 2019 it imported 830,000 tonnes of refined zinc metal and products. In the same year, the US exported 870,000 tonnes of zinc in ore concentrates, mostly from the Red Dog Mine in Alaska. During the period 2015-2018, imports were primarily from Canada (64%), Mexico (13%), Australia (7%), and Peru (7%).[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tolcin, Amy C. (20 January 2020). "Zinc". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ↑ "Teck 2019 Annual Report" (PDF). Vancouver, BC: Teck Resources Limited. 26 February 2020. p. 22. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ↑ "Industry Trend Analysis - Global Zinc Mining Outlook" (PDF). Mining.com. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ The world's top three zinc mines, Investing News.

- ↑ "About Red Dog". Teck. Vancouver, BC: Teck Resources Limited. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ↑ "Greens Creek Admiralty Island, Alaska". Coeur d’Alene, ID: Hecla Mining Company. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ "Lucky Friday Mullan, Idaho". Coeur d'Alene, ID: Hecla Mining Company. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ "Annual Report 2018" (PDF). Budel, The Netherlands: Nyrstar NV. 27 May 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- 1 2 Long, Keith R.; DeYoung, Jr., John H.; Ludington, Stephen D. (1998). Database of significant deposits of gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc in the United States (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Harrison, Donald K. (1989). "The Mineral Industry of New Jersey". Minerals Yearbook. Washington DC: United States Bureau of Mines. p. 331. ISBN 9780160359316. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Foley, Nora K. (2002). "A geoenvironmental lifecyle model: the Austinville platform carbonate deposit, Virginia". Progress on Geoenvironmental Models for Selected Mineral Deposit Types (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U. S. Geological Survey. p. 101. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Zinc, in Minerals Summary 2015, US Geological Survey.

- ↑ R.A. Heindl, '"Zinc," in Mineral Facts and Problems, US Bureau of Mines, Bulletin 650, 1970, p.814.

- ↑ World Mineral Production 2007-11, British Geological Survey, 2013.