Zangezur (Armenian: Զանգեզուր) is a historical and geographical region in Eastern Armenia[1][2][3] on the slopes of the Zangezur Mountains which largely corresponds to the Syunik Province of the Republic of Armenia. It was ceded to Russia by Qajar Iran according to the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. In Soviet times, the Goris, Kapan, Meghri and Sisian regions of the Armenian SSR were located within Zangezur, which in 1995 became part of the Syunik Province of Armenia.

Etymology

There are several theories about of the origin of the name Zangezur. According to Armenian scholar Ghevont Alishan, Zangezur is derived from the name of Dzagadzor fortress (now a village near Goris), which was named after a patriarch of the Sisak clan, Dzagik. Over time the name Dzagadzor changed and became Zangezur.[4]

Some sources also mention a possible connection between the name Zangezur and another toponym—the name of the Tsakedzor gorge (Armenian: Ծակեձոր, from the Armenian tsak - "hole", dzor - "gorge, ravine")[5] located to the northwest of Goris in the valley of the Goris River.[6]

There are also various explanations of the name stemming from folk tradition and legends. For example, the name is interpreted as a combination of Armenian zang ("bell") and dzor ("gorge") or alternatively as zang and zor ("power"), that is, a powerful bell.[4] There was a monastery about 2 kilometers away from Goris which had a loud bell.[4] Another tradition connects the name with the time of the conquests of Timur. According to this tradition, an Armenian prince named Mher offered his help to Timur, saying that he will not be able to conquer Syunik as long as there is the great bell in the village of Khot which will notify the principality in case of danger. Timur promised gold and power to Mher if he would silence the bell, and the latter with his conspirators lit a fire under the bell at night, muffling its sound. When Timur's army crossed the Aras River and invaded Syunik, attempts to notify the people using the bell were in vain. The principality fell overnight, and people asked in amazement "why didn't they ring the bell?" Some answered "ringing in vain", in Armenian: “zange zur e” (Armenian: զանգը զուր է). After that, the principality was also called Zangezur.[7]

Historical outline

Historically Zangezur was the southern part of the ancient Armenian province of Syunik. A. Redgate notes that the discovery of an Athenian coin of the 6th century BC in Zangezur indicates the presence of trade relations between Armenia and Asia Minor.[8] Inscriptions of the king of Great Armenia Artashes I (189–160 BC) have been found on the territory of Zangezur.[9] At the beginning of the 4th century, Syunik, along with other provinces of Armenia,[10] was converted to Christianity.[11] Of the twelve gavars (regions) of Syunik, seven were located within Zangezur (Chaguk, Agakhechk, Gaband, Bagk or Balk, Dzork, Arevik and Kusakan[12]). At the beginning of the 5th century, the Armenian scientist and educator Mesrop Mashtots conducted preaching and educational activities here.[13] From 428 to the beginning of the 7th century it was a part of the Armenian province of Persia. In the middle of the 7th century, Zangezur, along with the whole of Armenia, was conquered by the Arabs.

At the end of the 9th century, Zangezur, as a part of Syunik,[14] became a part of the Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia.[15] Later, it became a part of the Kingdom of Syunik (this was due to the fact that in 970–980s the political center of the Syunik region began to move to the south, to the gavar of Balk).

In 1170 the Kingdom of Syunik was defeated by the Seljuks. After the expulsion of the Seljuks, an Armenian principality ruled by the Orbelians existed in this territory (in 1236 they submitted to the Mongols). The principality fell in the first half of the 15th century[16] as a result of several invasions of Khan Tokhtamysh, Timur, the Turkoman tribes of Kara-Koyunlu, and the Timurid Shah Rukh.[17]

In the 15th century, Zangezur fell under the rule of the Kara-Koyunlu confederation of Turkic nomadic tribes, and later under the rule of the Ak-Koyunlu. The domination of the Mongol Ilkhans and especially the Turkmen conquerors Kara-Koyunlu and Ak-Koyunlu had extremely grave consequences: the productive forces were destroyed, part of the population was plundered and exterminated, and many cultural monuments were destroyed.[18] Lands were taken away from the local population and were settled by newcomer nomads,[19] and part of the Armenian population was forced to emigrate from their historical lands.

In the 16th century, Zangezur became a part of the Tabriz beglerbegdom of the Safavid state, and from the second half of the 18th century it was a part of the Karabakh Khanate.[20] During the 16th-17th centuries, Armenian feudal meliks continued to exist in Zangezur, along with Karabakh and Lori.[21]

In the 17th–18th centuries, Zangezur and some neighboring regions became the area of the liberation struggle of the Armenian people against the Ottoman Empire and Persia.[22] In 1722, an Armenian uprising broke out in Zangezur and Karabakh. A few years later, under the leadership of David Bek, Mkhitar Bek and Ter-Avetis, the Armenians fought against the Ottoman invaders. The Persian Shah Tahmasp II recognized the authority of David Bek over this region.[23]

According to the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813, Zangezur was ceded to the Russian Empire. On January 25, 1868, when the Elisabethpol Governorate was created, the Zangezur district was formed from a part of the Shusha district of the Baku province and the Ordubad district of the Erivan province.

20th and 21st centuries

After the October Revolution of 1917 and the creation and disintegration of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federal Republic, disputes arose between the newly created republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan over the ownership of a number of territories with a mixed population, including Zangezur, which also became the site of fierce Armenian-Azerbaijani clashes.[24]

Having entered into conflict with both the British interventionists and the Armenian government, the Armenian military commander Andranik withdrew his army from Zangezur to Echmiadzin and in April 1919 disbanded it. In September 1919, after the withdrawal of British troops, Garegin Nzhdeh was appointed head of the defense of the southern part of Zangezur (Kapan), while Poghos Ter-Davtyan was charged with defending its northern part (Sisian). In November, near Geryusy (Goris), Armenian troops managed to stop an Azerbaijani offensive, after which they launched a counterattack.

On April 27, 1920, the units of the 11th Army of the Red Army crossed the border of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and entered Baku on April 28. Here the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed.

On August 10, 1920, an agreement was concluded between the First Republic of Armenia and the RSFSR, according to which Soviet troops were sent to the disputed regions (Karabakh, Zangezur and Nakhichevan) until the settlement of territorial disputes. After the signing of the agreement, General Dro, who commanded the Armenian troops in Zangezur, left Zangezur, but his assistants – the commander of the Kapan region Garegin Nzhdeh and the commander of the Sisian region Poghos Ter-Davtyan – refused to recognize the agreement, fearing that Zangezur would be surrendered to Soviet Azerbaijan.

Dashnak detachments began a partisan war against Soviet troops and allied Turkish units. In early October 1920, a massive uprising against Soviet power broke out in the region. Ter-Davtyan soon died in battles with the Red Army, and Nzhdeh single-handedly led the uprising. By the end of November, two brigades of the 11th Army of the Red Army and several Turkish battalions (a total of 1200 Turks) were defeated by the rebels, and Zangezur completely came under the control of the rebels.

On December 25, the congress held in the Tatev Monastery proclaimed the "Autonomous Syunik Republic", which was actually headed by Nzhdeh, who assumed the ancient title of sparapet (commander-in-chief). Subsequently, Nzhdeh also extended his power to part of Nagorno-Karabakh, joining with the rebels operating there.

Meanwhile, on November 29, 1920, Soviet power was proclaimed in Armenia, after which on November 30, the AzRevCom of Soviet Azerbaijan, declaring its intention to end territorial disputes, agreed to the inclusion of Zangezur in the newly formed Soviet Armenia.[25][26]

In December 1920, an agreement was concluded between the RSFSR and Armenia, according to which Zangezur was assigned to the Armenian SSR.[27]

After the defeat of the February Uprising in central Armenia, parts of the rebels moved to Zangezur and joined the Nzhdeh's forces.

On April 27, 1921, the Republic of Mountainous Armenia was proclaimed in the territory controlled by the rebels, in which Nzhdeh took the posts of Prime Minister, Minister of War and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In connection with the transition of the Red Army units to the offensive, on July 9, 1921, Nzhdeh, having secured guarantees from the leadership of Soviet Armenia regarding the preservation of Zangezur as a part of Armenia, went to Iran with the remaining rebels.[28]

According to the agricultural census of 1922, the population of the part of the Zangezur district that seceded from the Armenian SSR numbered 63,533 thousand people, including 56,886 thousand (89.5%) Armenians, 6,464 thousand (10.2%) Turko-Tatars (Azerbaijanis) and 182 (0.3%) Russians.[29] The Armenian percentage has been cited as somewhat smaller before the First World War but that figure took in several lowland districts and even so had always shown a clear Armenian majority.[30]

Another aggravation of interethnic relations in this region took place in the late 1980s, against the backdrop of the Karabakh conflict, during which all of the Azerbaijanis living in Zangezur and other parts of Armenia fled to Azerbaijan concurrently with the flight of Armenians from Azerbaijan to Armenia.

In Soviet times, the railways Ordubad-Agarak-Meghri-Minjivan and Kapan-Zangelan-Minjivan passed through the territory of Zangezur. The railway communication in this section was stopped with the beginning of the first Karabakh war. The land connection of Nakhichevan with Azerbaijan through Armenia was interrupted.[31]

Industry

In Zangezur, the Kajaran copper-molybdenum plant, the largest in Armenia plant for the enrichment of copper-molybdenum ores, operates, exploiting the Kajaran copper-molybdenum deposit, one of the largest deposits of copper-molybdenum ores in the world. The part of molybdenum in this deposit in the world is approximately 7%. The plant's products are exported to Europe.

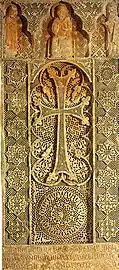

Gallery

Vahanavank, 10th-11th century monastery

Vahanavank, 10th-11th century monastery 4th-6th century bridge near the town of Kapan

4th-6th century bridge near the town of Kapan Meghri, Church of the Holy Mother of God, 1673

Meghri, Church of the Holy Mother of God, 1673 13th century Armenian manuscript from Zangezur

13th century Armenian manuscript from Zangezur

Tatev hermitage, 17th-18th centuries

Tatev hermitage, 17th-18th centuries Zorats-Karer prehistoric observatory. 3rd-5th millennia BC

Zorats-Karer prehistoric observatory. 3rd-5th millennia BC

References

- ↑ Петрушевский, И. П. (1960). Земледелие и аграрные отношения в Иране XIII-XIV веков. Л.: Изд. АН СССР. p. 79.

- ↑ Волкова, Н. Г. (1969). "Этнические процессы в Закавказье в XIX-XX вв". Кавказский этнографический сборник. IV: 29.

- ↑ Токарев, С. А. (1968). Основы этнографии. М.: Высшая школа. p. 303.

- 1 2 3 Avetisyan, Kamsar (1979). Hayrenagitakan ētyudner (in Armenian). Yerevan: Sovetakan grogh.

- ↑ Мкртчян, Ш. М. (1988). Историко-архитектурные памятники Нагорного Карабаха. Ереван: Айастан. p. 105.

- ↑ Мелик-Башхян, Ст. С. (1988). Словарь топонимов Армении и прилегающих территорий. Ер. p. 830.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Дорога Мгера. Армянские легенды и предания. p. 22.

- ↑ Redgate, A. E. (2000). The Armenians. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 60.

- ↑ Периханян, А. Г. (1965). "Арамейская надпись из Зангезура (Некоторые вопросы среднеиранской диалектологии)". Ист.-филол. журн. 4: 107–128.

- ↑ Агатангелос. "История Армении»; «Спасительное обращение страны нашей Армении через святого мужа-мученика". p. 795 CXII.

- ↑ Орбелян, Степанос (1985). История Сюника. Ер.: Советакан грох. p. 421.

- ↑ Багдасарян, А. Зангезур. Армянская советская энциклопедия. Ер. p. 656.

- ↑ Henri-Jean Martin (1995). The History and Power of Writing. University of Chicago Press. p. 39.

- ↑ Зангезур // Большой энциклопедический словарь. 2012. p. 467.

- ↑ Сюникское царство // Большая советская энциклопедия. Советская энциклопедия. 1969–1978.

- ↑ Петрушевский, И. П. (1949). Очерки по истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI – начале XIX вв. Л. p. 157.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Hovhannisian, R. G. (1997). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5.

- ↑ Петрушевский, И. П. (1949). Очерки по истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI – начале XIX вв. Л. p. 35.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Закавказье в XI—XV вв. // История Востока. Восточная литература. 1997.

- ↑ Петрушевский, И. П. (1949). Очерки истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI—XIX вв. Л.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Петрушевский, И. П. (1949). Очерки истории феодальных отношений в Азербайджане и Армении в XVI—XIX вв. Л. p. 126.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Зангезур // Большой энциклопедический словарь. 2012. p. 467.

- ↑ Bournoutian, G. "Encyclopædia Iranica. Armenia and Iran".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Волкова, Н. Г. (1969). "Этнические процессы в Закавказье в XIX—XX веках". Кавказский Этнографический сборник. IV: 10.

- ↑ Нагорный Карабах в 1918—1923 гг. Сборник документов и материалов. Ереван. 1992. p. 601.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ К истории образования Нагорно-Карабахской автономной области Азербайджанской ССР. Документы и материалы. Баку. 1989. p. 44.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Altstadt, Audrey L. (1992). The Azerbaijani Turks: power and identity under Russian rule. Hoover Press. p. 116.

- ↑ "Нжде в Энциклопедии Геноцид.ру".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Население Армении по полу, возрасту, грамотности и национальности. Материалы сельскохозяйственной переписи 1922 г.". руды Центрального Статистического Управления: 74–75. 1924.

- ↑ Wright, John F. R., ed. (2003). Transcaucasian Boundaries. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 101. ISBN 9780203214473.

- ↑ "Вышли в коридор: Азербайджан готовится проложить дорогу через Армению". May 13, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)