Xicalcoliuhqui (also referred to as a "step fret" or "stepped fret" design and greca in Spanish) is a common motif in Mesoamerican art.[1][2][3][4] It is composed of three or more steps connected to a hook or spiral, reminiscent of a "greek-key" meander.[5] Pre-Columbian examples may be found on everything from jewelry, masks, ceramics, sculpture, textiles and featherwork to painted murals, codices and architectural elements of buildings.[6][7][8] The motif has been in continual use from the pre-Columbian era to the present.[2][9]

Connotations

The word xicalcoliuhqui (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ʃikaɬkoˈliʍki]) means "twisted gourd" (xical- "gourdbowl" and coliuhqui "twisted") in Nahuatl.[1][2][10] The motif is associated with many ideas, and is variously thought to depict water, waves, clouds, lightning, a serpent or serpent-deity like the mythological fire or feathered serpents, as well as more philosophical ideas like cyclical movement, or the life-giving connection between the light of the sun and the earth, and it may have been a protection against death, but no single meaning is universally accepted.[2][6][9] It is also possible that the motif represents the cut conch shell which is an emblem of Ehecatl, the wind god, an aspect of Quetzalcoatl.[6][11] It seems likely that the multivalent nature of the symbol gave rise to its potency and longevity.[6]

Xicalcoliuhqui chimalli, the stepped-fret shield

Xicalcoliuhqui chimalli, are shields featuring a single iteration of the stepped fret motif which were painted or covered with featherwork.[4] They are depicted frequently in the Codex Mendoza, and many other central Mexican codices, usually with the xicalcoliuhqui design shown in yellow and green.[2]

Architectural embellishments

The xicalcoliuhqui motif appears in embellishments on temples and other buildings at archaeological sites around Mexico.

References

- 1 2 Hernández Sánchez, Gilda. ' 'Ceramics and the Spanish Conquest: Response and Continuity of Indigenous Pottery Technology in Central Mexico' '. BRILL, 2011. ISBN 9004217452. pg 69

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berdan, Frances and Anawalt, Patricia Rieff. ‘ ‘Codex Mendoza: Four-Volume Set’ ‘. University of California Press, 1992. ISBN 0520908694. pg 190, 193

- ↑ Nicholson, H. B. The Mixteca-Puebla Concept Revisited. The Art and Iconography of Late Post-Classic Central Mexico: A Conference at Dumbarton Oaks, October 22nd and 23rd, 1977 ed. Boone, Elizabeth Hill. Dumbarton Oaks, 1982. ISBN 0884021106. pg 229.

- 1 2 Pohl, John. Aztec Warrior: AD1325-1521. Osprey Publishing, 2012 ISBN 1780967578 pg 20, 22.

- ↑ Enciso, Jorge. ‘ ‘Design Motifs of Ancient Mexico’ ‘ Courier Corporation, 1953. ISBN 0486200841 pg. 21-30

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sharp, Rosemary. Chacs and Chiefs: The Iconology of Mosaic Stone Sculpture in Pre-conquest Yucatán, Mexico, Issues 24-28. Dumbarton Oaks, 1981. ISBN 0884020991 pg. 6-10.

- ↑ Bernal, Ignacio. The Olmec World. University of California Press, 1969. ISBN 0520028910 pg 166.

- ↑ de la Fuente, Beatriz. La pintura mural prehispánica en México, Volume 1. UNAM, 1995. ISBN 9683647421. pg. 103

- 1 2 Montón-Subías, Sandra and Sánchez Romero, Margarita. Engendering social dynamics: the archaeology of maintenance activities. British Archaeological Reports British Series, Volume 1862. Archaeopress, 2008. ISBN 1407303457. pg ii

- ↑ de Sahagún, Fray Bernardino. ‘ ‘Primeros Memoriales’ ‘ ed. Sullivan, Thelma D. et al. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997, pg 99

- ↑ McCafferty, Sharisse and McCafferty, Geoffrey G. Weaving Space: Textile Imagery and Landscape in the Mixtec Codices. Space and Spatial Analysis in Archaeology. ed Elizabeth C. Robertson University of Calgary. Archaeological Association. Conference. UNM Press, 2006. ISBN 0826340229. pg 339

- ↑ Mexico Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic, Volume 1. Saragoza, Alex, Ambrosi, Ana Paula, Zárate, Silvia Dolores eds. ABC-CLIO, 2012. ISBN 0313349487 pg. 35.

Gallery

A miniature xicalcoliuhqui chimalli, or step-fret shield from Yanhuitlan, Oaxaca. |

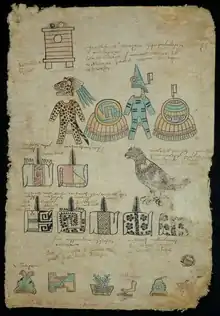

This page from the Matrícula de tributos shows the xicalcoliuhqui motif in three places, on the xicalcoliuhqui chimalli, the shield to the right of the jaguar-warrior costume, as well as on the two bundles on the left side of the page. |

.jpg.webp) An example of xicalcoliuhqui motif on the bottom left from the Codex Magliabechiano, folio 6r. |

A Xicalcoliuhqui Chimalli |