William Hodge Kitchin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from North Carolina's 2nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1879 – March 3, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Curtis Hooks Brogden |

| Succeeded by | Orlando Hubbs |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 22, 1837 near Lauderdale County, Alabama |

| Died | February 2, 1901 (aged 63) Scotland Neck, North Carolina, US |

| Political party | Democrat Populists |

| Alma mater | Emory and Henry College |

William Hodge Kitchin (December 22, 1837 – February 2, 1901) was an American lawyer, Confederate soldier and politician who served one-term U.S. Congressman from North Carolina as a Democrat. A white supremacist, Kitchin spent much of his political career attempting to curb African American advances within the state, although he briefly was a member of the Populists which worked with African Americans.

Early and family life

Kitchin was born in Lauderdale County, Alabama on December 22, 1837. He moved with his parents to North Carolina in 1841 and later attended Emory and Henry College in Emory, Virginia. He left college in April 1861 to enlist in the Confederate States Army, was promoted to the rank of captain in 1863 and served throughout the Civil War.

In 1864, Kitchin married Maria Figures Arrington, who would bear eight sons and a daughter who survived to adulthood.

Kitchin's sons and daughters, in order of their ages were: Samuel Boaz, planter; William Walton Kitchin, lawyer, Congressman, governor; Claude Kitchin, lawyer, Congressman; John Arrington, planter; Paul, lawyer, state senator; Gertrude (Mrs. A. McDowell): Richard Vann, various; Annie Maria (Mrs. Charles L. McDowell); Thurman Delna, physician, President of Wake Forest College; Leland H., planter; Teddy Alston, various.[1]

Legal career

After the war, Kitchin studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1869 and practiced in Scotland Neck, North Carolina. He traveled to California to settle a land claim that resulted in a princely fee for him of $20,000; as an obituary in his home town newspaper noted upon his death thirty years later, the money made him "easy" in the business world. He was an active Mason.

Political career

In 1878, Kitchin was elected from North Carolina's 2nd U.S. House district as a Democrat to the Forty-sixth United States Congress (March 4, 1879 – March 3, 1881). His election was tainted by accusations of irregularities and was aided by a split among Republicans between candidates James E. O'Hara and James Harris (both African-Americans).[2] O'Hara unsuccessfully contested the election.[3][4]

Kitchin failed to win reelection in 1880, and returned to North Carolina and his legal career, building a house named "Gallberry" in 1885.[5]

A bombastic orator, especially harsh toward black political influence in his area of the state, Kitchin defeated a former slave to win his Congressional term. He split with the Democratic party in 1890, criticizing President Grover Cleveland for pandering to the black vote. He briefly joined the People's Party or Populists, served on its state executive committee in the mid-1890s, and worked with them for a time to build an alliance with African American voters. Although disillusioned with his new allies because of the "fusion" rule between Populists and Republicans in the state legislature in 1895, he was a delegate to the national Populist convention in 1896 where he worked to gain the party's nomination of the Democratic slate (William J. Bryan and Arthur Sewall) that year.[6] He returned to the Democratic party, now one of "white men and white metal" (silver), both important issues to him.

Death and legacy

Kitchin died in Scotland Neck, North Carolina on February 2, 1901. Although he declared himself as a "militant Baptist", he was interred in the family plot in the cemetery of Trinity Episcopal Church. Kitchin began a North Carolina political dynasty, as two of his eight sons, Claude Kitchin and William Walton Kitchin, and a grandson, Alvin Paul Kitchin, became prominent politicians, and another son, Thurman Delna Kitchin, was a long-time president of Wake Forest College. North Carolina erected a highway marker near his home, Gallberry.[7]

References

- ↑ Alex Arnett, Claude Kitchin and the Wilson War Policies (New York: Russell and Russell, 1937), 9

- ↑ Eric Anderson (1981). Race and Politics in North Carolina, 1872–1901. LSU Press. ISBN 0-8071-0784-0.

- ↑ United States Congress. "O'HARA, James Edward (id: O000054)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑ James H. Ellsworth (1883). Digest of Election Cases. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 378.

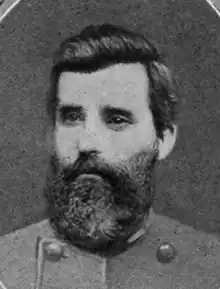

william h. kitchin.

- ↑ "Marker: E-47".

- ↑ James Logan Hunt (2003). Marion Butler and American populism. UNC Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-8078-2770-3.

w. h. kitchin populist.

- ↑ "Marker: E-47".

External links

United States Congress. "KITCHIN, William Hodges (id: K000251)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.