Willem Boy (French: Guillaume Boyen) (1520 – 1592) was a Flemish painter, sculptor, and architect active in Sweden from around 1558 until his death.

Few of Boy's works have survived, and he is mostly remembered for the sarcophagus of King Gustav I in the Uppsala Cathedral.

He is believed to have originated from Mechelen and to have arrived in Sweden no later than 1558 during the late reign of Gustav Vasa to work as a painter of portraits. Within a few years he became one of the country's leading artists whose talents proved useful in a wide range of fields; he, for example, led the construction of the fortification at Vaxholm in 1589. Even though few of his works have survived, his influence on Swedish culture was considerable.[1]

Sarcophagi

Boy is thought to have soon returned to Flanders to spend six years working on the sarcophagus of Gustav Vasa and his two first consorts Catherine and Margaret. In 1571 he was finally able to send the statues of the king and his wives to Sweden. In 1572 he went to England to buy marble and alabaster for the rest of the monument. However, in 1567 he had borrowed 1.000 daler for the project and when the bond proprietor in Antwerp was informed the statues happened to be in the city, she presented the bonds to the city magistrates and, as the defendant failed to present himself, the statues were confiscated.[2]

When Boy was informed of the situation he immediately managed to have the repayment postponed and wrote a letter to the Swedish monarch who happened to be in Kalmar. The infuriated king wrote a letter to the Duke of Alba to have the monument sent to Sweden. Furthermore, to ensure Dutch merchants in Sweden would support his cause, he threatened to free them from their favoured position and demanded that they produce a security at least equal to the value of the monument. The Dutch magistrates eventually backed down and Boy was given a respite. The sarcophagus was safely delivered to Uppsala in 1583. The main volume in red marble measures 2.77×2×1.36 m with pillars on the corners 1.68 m tall. The statues are made of white marble with crowns and sceptres in gilded bronze.[2]

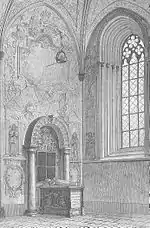

In 1584, he worked on the grave monument of Catherine Jagellon, a monument crowned by marble vault carried by pillars in front of which rests the queen on her sarcophagus.[1]

Palaces

Stockholm

While Boy was abroad, Eric had devoted himself to various architectonic projects; he had the Franciscan monastery in Stockholm (today Riddarholmskyrkan) rebuilt; he appointed Arendt de Roy to repair and enlarge Vadstena Castle; and he employed the Paar brothers at the Castles in Uppsala and Kalmar. However, the king's main undertaking was undoubtedly the castle in Stockholm where Boy was to spend the remaining 16 years of his life.[2]

The king had employed an artist called Anders Målare to lead the works at the castles in Stockholm and at Svartsjö, but in letters in 1573 the king complained Målare failed to accomplish his duties due to age and poor health. Having no one else to choose from, he appointed his chamberlain Phillipe Kern to replace the Swedish artist. Kern, however, proved to be untrustworthy and within a few years had provided himself with sufficient materials to build his private house. To hide his deed, Kern added the names of his subordinates to material specifications and Boy's name appears among them. This situation did not last, however, and in a letter of 25 June 1576 the king mentions Boy as the man leading the works, and on 10 July Boy is addressed "Master Wilhelm, architect at the Stockholm Palace".[2]

As neither the castle nor any associated drawings by architects involved have survived, it is difficult to know what Boy's contribution to the structure was. However, surviving financial documents and letters written by the king while he resided elsewhere offer some hints. During his work on the castle in Stockholm, Boy had to supervise hundreds of employees and ensure materials were delivered in proper order, while keeping his demanding king happy. In 1577, repairs on the royal suite were completed. Two years later, stairs were built south of the castle while the northern gate was furnished with a tower adorned with a spire and a stone tablet carrying the royal coat of arms. Over subsequent years, he was involved in various undertakings at the palace, both decorative work and engineering.[2]

From 1586 Boy focused on the royal church and the decoration of the castle's large square-shaped room. The church was 130 feet in length and located along the northern side of the courtyard. It was topped by a bell tower on which Boy worked in 1589. In 1591 glass and lead were bought for the windows. The king ordered lavish decorations for the square room, including a ceiling in gilded copper for which the gilding alone cost the equivalent of 100 ship pounds (170.000 kg) of copper, which failed to satisfy the king who sent 30 Hungarian gold florins in 1589 to have a large sphere gilded. Boy spent the last years of his life producing sketches for various other projects in the palace, including gilded cornices in the dining room, ashlars for the so-called "Summer Room" and for the two towers flanking the eastern gate, and he had the spires of the three crown tower raised by 20–30 feet.[2]

Svartsjö

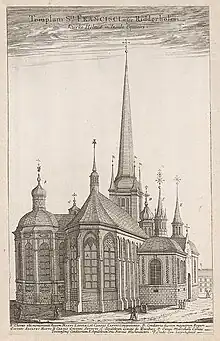

Engraving from Antiqua et hodierna.

A monastery built by Lake Mälaren in the 15th century was made royal property by King Gustav I and, under his sons Eric and John, it was transformed into the Svartsjö Palace. The responsible architects were those working at the royal palace in Stockholm. The main building was a large cube crowned by a cupola and small towers with a round court surrounded by arcades in two stories in front. While it is difficult to determine which parts Boy was responsible for, he was working on the cupola and the towers in 1579; a correspondence between him and the king mentions the completion of the roof; and in 1586 the royal domains and a chapel near the palace were completed; and two years later the surrounding land was arranged in accordance with Boy's plans. However, when the king paid a visit to the palace in 1591, he was not pleased; construction on the palace in Stockholm had kept Boy busy and the palace at Svartsjö had been neglected and remained uncompleted at the time of the architect's death. The palace was destroyed by fire a century later, a fate shared with most of his works, which seems to confirm Boy was apparently not an architect in the proper sense.[2]

Drottningholm

Detail from an engraving in Antiqua et Hodierna.

Starting in 1576, Boy led the construction of the palace that preceded the extant Baroque version of the Drottningholm Palace. The royal mansion named Torvesund on the location was rebuilt into a palace by King John III, who was able to take a few rooms in possession in 1580, and the construction seems to have been complete four years later, save for the adornment of the interior.[3]

The centre of this rectangular Renaissance palace was the vaulted palace church, with surrounding rooms connected by open arcades and loggias. The choirs of the church possibly had ogive and rose windows like those at Vadstena Castle. Characteristic of the palaces built during this era were towers and pinnacles with adorned hoods, bay windows, arcades, and galleries and these were probably also prominent features of the Renaissance palace at Drottningholm.[3]

John named the palace after Queen Catherine Jagellon, which indicates it was never important as a military bastion. While the palace and its chapel were of great importance to the queen, it remained unfinished at the time of her death. An important prototype for the palace was the Wawel Castle in Kraków, and as at Drottningholm, palaces with church gables projecting out of the façades were built throughout Catholic Poland, and a similar scheme was used in Sweden at Borgholm, at the Vadstena Castle, and at the Uppsala Castle, the enlargement of which was also led by Boy.[3]

Drottningholm became an important centre for Counter-Reformation groups while plague tormented Stockholm in 1579. It eventually burned down in 1661, but even before that the Catholic appearance the palace must have had caused it to be neglected and uncompleted. It was passed back and forth between various nobles and gradually decayed, before an inventory around 1640 described it as a ruin with broken windows.[3]

Churches

In 1581, the king ordered the city to add a tall and beautiful spire to the Riddarholmen Church. As the proposal delivered by the magistrate failed to impress the king, he turned to his favourite architect in 1584, and Boy finally had a proposal ready which pleased the king by 1589. The simple and narrow spire lasted until lightning destroyed it in 1835.[2]

King Eric also ordered two other churches to be constructed in the capital: one dedicated to St Henry and the other to the Holy Trinity. From contemporary accounts it is known the first was bought and used by the Finnish and German parishes in 1593. In a letter dated 1584 Boy is said to have led the construction work on St Thomas, and in a letter in 1588 the king orders Boy to decorate the western gable and add a tall spire without replacing the old one. The foundation for the Trinity was laid in 1589 to the plans of Boy but, by the death of the king in 1592, construction work had stopped, with the walls only reaching 6 feet above the ground. St Thomas was rebuilt and enlarged in the 17th century and still exists: Charles IX handed it over to the German parish who renamed it St Gertrude.[2]

Additionally, Boy is believed to be responsible for the design of John III's Renaissance reconstruction of St James's church in Stockholm, built around 1520–1592 and featuring a central nave flanked by two tall aisles resting on sandstone columns.[4]

Portraits

The alabaster monument of Princess Isabella (1564–1566), daughter of John III, is in Strängnäs Cathedral.[1]

Two portraits of Gustav Vasa are assumed to have been made by him: a wooden relief and possibly a watercolour, both found at Gripsholm Castle.[1]

See also Vasa sarcophagi above.

Payment

His initial salary was 200 daler[5] silver coins, a court dress, and emoluments in kind.[1]

On 28 February 1562 Boy travelled to Antwerp, and in 1565 he arrived in Stockholm where King John III appointed him a salary of 1.600 marks silver coins annually and emoluments in kind (corn, hops, a court dress, and lodging).

In 1577 he received 200 daler, 144 hectoliters of corn, 1 court dress, 10 pounds of hop, 1 barrel of salt, 1 barrel of butter, 3 oxen, 8 sheep, 6 pigs, 2 barrels of salmon, 1 barrel of cod, 10 pounds of pike, 1 barrel of herring, and fodder for a horse – in total worth 399½ daler.[2]

Work

- Three Crown Castle, Stockholm

- Gävle Castle, completed in 1597.[3]

- Monument of Gustav Vasa at the Uppsala Cathedral.

- Svartsjö Palace.

- Saint James's church, Stockholm, 1580-93.

- Drottningholm Palace

- Uppsala Castle

Notes

References

- Sandén. Gudrun (2000-09-19). "Villhelm Boy" (PDF) (in Swedish). Upplands-Bro Kulturhistoriska Forskningsinstitut. pp. 6–10. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- "Boy, Willem" (in Swedish). Project Runeberg, Nordisk Familjebok. 1905. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- "Gävle Castle". Swedish National Property Board. Archived from the original on 2007-12-20. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- Bedoire, Fredric (2004). "Johan III:s Drottningholm" (PDF) (in Swedish). Statens fastighetsverk (Swedish National Property Board). pp. 12–13. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- "S:t Jacobs kyrkas historia" (in Swedish). Stockholm domkyrkoförsamling. Retrieved 2008-01-24.