Pensacola | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Pensacola | |

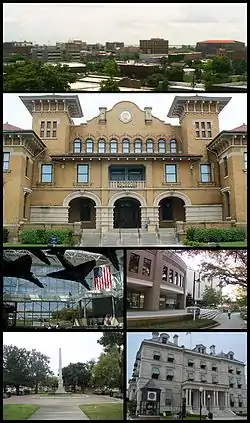

Clockwise from top: Pensacola skyline, Pensacola Museum of History, University of West Florida Library, Escambia County Courthouse, William Dudley Chipley Obelisk, National Naval Aviation Museum | |

Location in Escambia County and the state of Florida | |

Pensacola Location in Florida  Pensacola Location in the United States  Pensacola Pensacola (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 30°25′17″N 87°13′02″W / 30.42139°N 87.21722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Escambia |

| First settled | 1559 |

| Resettled | 1667 |

| Incorporated | 1821 |

| Founded by | Don Tristan de Luna |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Pensacola City Council |

| • Mayor | D. C. Reeves |

| • Council Vice President | Delarian Wiggins |

| Area | |

| • City | 41.12 sq mi (106.49 km2) |

| • Land | 22.76 sq mi (58.95 km2) |

| • Water | 18.36 sq mi (47.54 km2) |

| • Metro | 1,669.30 sq mi (4,323.5 km2) |

| Elevation | 102 ft (31 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 54,312 |

| • Density | 2,386.19/sq mi (921.30/km2) |

| • Urban | 390,172 (US: 108th) |

| • Urban density | 1,486.2/sq mi (573.8/km2) |

| • Metro | 509,905 (US: 110th) |

| • Metro density | 1,669.30/sq mi (644.52/km2) |

| Demonym | Pensacolian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 32501, 32512, 32534, 32591, 32502, 32513, 32559, 32592, 32503, 32514, 32573, 32593, 32504, 32516, 32574, 32594, 32505, 32520, 32575, 32595, 32506, 32521, 32576, 32596, 32507, 32522, 32581, 32597, 32508, 32523, 32582, 32598, 32509, 32524, 32589, 32511, 32526, 32590 |

| Area code(s) | 850/448 |

| FIPS code | 12-55925[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0294117[3] |

| Website | www |

Pensacola (/ˌpɛnsəˈkoʊlə/ PEN-sə-KOH-lə) is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida.[4] Pensacola is the principal city of the Pensacola Metropolitan Area, which had an estimated 502,629 residents in 2019.[5] At the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312.

Pensacola was first settled by the Spanish in 1559, predating the establishment of St. Augustine by 6 years, although the settlement was abandoned due to a hurricane and not re-established until 1698. Pensacola is a seaport on Pensacola Bay, which is protected by the barrier island of Santa Rosa and connects to the Gulf of Mexico. A large United States Naval Air Station, the first in the United States, is located southwest of Pensacola near Warrington; it is the base of the Blue Angels flight demonstration team and the National Naval Aviation Museum. The main campus of the University of West Florida is situated north of the city center.

The area was originally inhabited by Muskogean-speaking peoples. The Pensacola people lived there at the time of European contact, and Creek people frequently visited and traded from present-day southern Alabama and Mississippi and southeast of Louisiana. Spanish explorer Tristán de Luna founded a short-lived settlement in 1559.[6] In 1698 the Spanish established a presidio in the area, from which the modern city gradually developed. The area changed hands several times as European powers competed in North America. During Florida's British rule (1763–1781), fortifications were strengthened.

It is nicknamed "The City of Five Flags", due to the five governments that have ruled it during its history: the flags of Spain (Castile), France, Great Britain, the United States of America, and the Confederate States of America. Other nicknames include "World's Whitest Beaches" (due to the white sand of Florida panhandle beaches), "Cradle of Naval Aviation", "Western Gate to the Sunshine State", "America's First Settlement", "Emerald Coast", and "P-Cola".

History

Spanish Empire 1559–1719, 1722–1763 and 1781–1821

French Empire 1719–1722

British Empire 1763–1781

United States 1821–1861

Confederate States of America 1861–1865

United States 1865 to present

Pre-European

The original inhabitants of the Pensacola Bay area were Native American peoples. At the time of European contact, a Muskogean-speaking tribe known to the Spanish as the Pensacola, lived in the region. This name was not recorded until 1677, but the tribe appears to be the source of the name "Pensacola" for the bay and thence the city.[7] Creek people, also Muskogean-speaking, came regularly from present-day southern Alabama to trade, so the peoples were part of a broader regional and even continental network of relations.[8]

The best-known Pensacola culture site in terms of archeology is the Bottle Creek site, a large site located 59 mi (95 km) west of Pensacola north of Mobile, Alabama. This site has at least 18 large earthwork mounds, five of which are arranged around a central plaza. Its main occupation was from 1250 CE to 1550. It was a ceremonial center for the Pensacola people and a gateway to their society. This site would have had easy access by a dugout canoe, the main mode of transportation used by the Pensacola.[9]

Spanish

The area's written recorded history begins in the 16th century, with documentation by Spanish explorers who were the first Europeans to reach the area. The expeditions of Pánfilo de Narváez in 1528 and Hernando de Soto in 1539 both visited Pensacola Bay, the latter of which documented the name "Bay of Ochuse".[10]

In the age of sailing ships Pensacola was the busiest port on the Gulf of Mexico, having the deepest harbor on the Gulf.[11]

In 1559, Tristán de Luna y Arellano landed with some 1,500 people on 11 ships from Veracruz, Mexico.[12][10][13][14] The expedition was to establish an outpost, ultimately called Santa María de Ochuse by Luna, as a base for Spanish efforts to colonize Santa Elena (present-day Parris Island, South Carolina.) But the colony was decimated by a hurricane on September 19, 1559,[12][10][14] which killed an unknown number of sailors and colonists, sank six ships, grounded a seventh, and ruined supplies.

The survivors struggled to survive, most moving inland to what is now central Alabama for several months in 1560 before returning to the coast; but in 1561, the effort was abandoned.[12][14] Some of the survivors eventually sailed to Santa Elena, but another storm struck there. Survivors made their way to Cuba and finally returned to Pensacola, where the remaining fifty at Pensacola were taken back to Veracruz. The Viceroy's advisers later concluded that northwest Florida was too dangerous to settle. They ignored it for 137 years.[12][14]

In the late 17th century, the French began exploring the lower Mississippi River with the intention of colonizing the region as part of La Louisiane or New France in North America. Fearful that Spanish territory would be threatened, the Spanish founded a new settlement in western Florida. In 1698 they established a fortified town near what is now Fort Barrancas, laying the foundation for permanent European-dominated settlement of the modern city of Pensacola.[15] The Spanish built three presidios in Pensacola:[16]

- Presidio Santa Maria de Galve (1698–1719): the presidio included fort San Carlos de Austria (east of present Fort Barrancas) and a village with church;[16]

- Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa (1722–1752): this next presidio was on western Santa Rosa Island near the site of present Fort Pickens, but hurricanes battered the island in 1741 and 1752. The garrison was moved to the mainland;[16]

- Presidio San Miguel de Panzacola (1754–1763): the final presidio was built about 5 mi (8 km) east of the first presidio; the present-day historic district of downtown Pensacola, named from "Panzacola", developed around the fort.[16]

During the early years of settlement, a tri-racial creole society developed. As a fortified trading post, the Spanish had mostly men stationed here. Some married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek or African women, both slave and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizos and mulattos. The Spanish encouraged fugitive slaves from the Southern colonies to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine,[17] but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola.

British

After years of settlement, the Spanish ceded Florida to the British in 1763 as a result of an exchange following British victory over both France and Spain in the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War), and French cession of its territories in North America. The British designated Pensacola as the capital of their new colony of West Florida. From 1763, the British strengthened defenses around the mainland area of fort San Carlos de Barrancas, building the Royal Navy Redoubt. George Johnstone was appointed as the first British Governor, and in 1764 a colonial assembly was established.[18][19] The structure of the colony was modeled after the existing British colonies in America, as opposed to French Canada, which was based on a different structure. West Florida was invited to send delegates to the First Continental Congress which was convened to present colonial grievances against the British Parliament to George III, but along with several other colonies, including East Florida, they declined the invitation. Once the American War of Independence had broken out, the colonists remained overwhelmingly loyal to the Crown. In 1778 the Willing Expedition proceeded with a small force down the Mississippi, ransacking estates and plantations, until they were eventually defeated by a local militia. In the wake of this, the area received a small number of British reinforcements.

British military resources were limited and Pensacola ranked fairly low on their list of priorities. For this reason only small token amounts of British military forces were ever sent to defend Pensacola. This was in contrast to colonies such as South Carolina, where large numbers of British soldiers were sent.[20] After Spain joined the American Revolution in 1779 on the side of the rebels, Spanish forces captured the city in the 1781 Siege of Pensacola, gaining control of West Florida.[13] After the war, the British officially ceded both West Florida and East Florida to Spain as part of the post-war peace settlement.

In 1785 many Creek from southern Alabama and Georgia came to trade and Pensacola developed as a major trade center. It was a garrison town, predominantly males in the military or trade.[8] Americans made raids into the area, and settlers pressured the federal government to gain control of this territory.

United States

In the final stages of the War of 1812, American troops launched an offensive on Pensacola against the Spanish and British garrisons protecting the city, which surrendered after two days of fighting. Pensacola was conquered again by the US in 1818. In 1819, Spain and the United States negotiated the Adams–Onís Treaty, by which Spain recognized the American control over Florida in exchange of the American recognition of Spanish control over Texas.[13] A Spanish census of 1820 indicated 181 households in the town, with a third of mixed-blood. The people were predominantly French and Spanish Creole. Indians in the area were noted through records, travelers' accounts, and paintings of the era, including some by George Washington Sully and George Catlin. Creek women were also recorded in marriages to Spanish men, in court records or deeds.[8]

In 1821, with Andrew Jackson as provisional governor, Pensacola became part of the United States.[13] The Creek continued to interact with European Americans and African Americans, but the dominant whites increasingly imposed their binary racial classifications: white and black ("colored", within which were included free people of color, including Indians). However, American Indians and mestizos were identified separately in court and Catholic church records, and as Indians in censuses up until 1840, attesting to their presence in the society. After that, the Creek were not separately identified as Indian, but the people did not disappear. Even after removal of many Seminole to Indian Territory, Indians, often of mixed-race but culturally identifying as Muskogean, lived throughout Florida.[8]

St. Michael's Cemetery was established in the 18th century at a location in a south central part of the city, which developed as the Downtown area. Initially owned by the Church of St. Michael, it is now owned and managed by St. Michael's Cemetery Foundation of Pensacola, Inc.[21] Preliminary studies indicate that there are over 3,200 marked burials as well as a large number unmarked.[21]

Tensions between the white community and Indians tended to increase during the Removal era. In addition, an increasing proportion of Anglo-Americans, who constituted the majority of whites by 1840, led to a hardening of racial discrimination in the area.[8] There was disapproval of white men living with women of color, which had previously been accepted. In 1853 the legislature passed a bill prohibiting Indians from living in the state, and provided for capture and removal to Indian Territory.[8]

_(14762797155).jpg.webp)

While the bill excluded mixed-Indians and those already living in white communities, they went "underground" to escape persecution. No Indians were listed in late 19th and early 20th century censuses for Escambia County. People of Indian descent were forced into the white or black communities by appearance, and officially, in terms of records, "disappeared". It was a pattern repeated in many Southern settlements. Children of white fathers and Indian mothers were not designated as Indian in the late 19th century, whereas children of blacks or mulattos were classified within the black community, related to laws during the slavery years.[8]

Pensacola experienced the Civil War when in 1861 Confederate forces lost the nearby Battle of Santa Rosa Island and federal forces of the United States subsequently failed to win the Battle of Pensacola. After the fall of New Orleans in 1862 the Confederacy abandoned the city and it was occupied by the North.[22] In June, 1861, the Pensacola Guards were mustered in as a company in the 1st Florida Infantry Regiment.[23]

In 1907–1908 there were 116 Creek in Pensacola who applied for the Eastern Cherokee enrollment, thinking that all Indians were eligible to enroll. Based on Alabama census records, most of these individuals have been found to be descendants of Creek who had migrated to the Pensacola area from southern Alabama after Indian removal of the 1830s.[8]

In 1908, a citywide streetcar strike occurred in the city, this led to state militia being stationed in the city and marital law being declared.[24][25]

Geography

Topography

Pensacola is located on the north side of Pensacola Bay. It is 59 mi (95 km) east of Mobile, Alabama, and 196 mi (315 km) west of Tallahassee, the capital of Florida. According to the United States Census Bureau, Pensacola has a total area of 40.7 sq mi (105.4 km2), consisting of 22.5 sq mi (58.4 km2) of land and 18.1 sq mi (47.0 km2), 44.62%, water.[26]

The land is sloped up northward from Pensacola Bay, with most of the city at an elevation above that which a potential hurricane storm surge could affect.[27]

Climate

Weather statistics since the late 20th century have been recorded at the airport. The city has seen single digit temperatures (below −12 °C) on three occasions: 5 °F (−15 °C) on January 21, 1985; 7 °F (−14 °C) on February 13, 1899; and 8 °F (−13 °C) on January 11, 1982.[28] According to the Köppen climate classification system, Pensacola has a humid subtropical climate,[29] (Köppen Cfa), with short, mild winters and hot, humid summers. Typical summer conditions have highs in the lower 90s °F (32–34 °C) and lows in the mid 70s °F (23–24 °C).[30] Afternoon or evening thunderstorms are common during the summer months. Due partly to the coastal location, temperatures above 100 °F (38 °C) are relatively rare, and last occurred in June 2011, when two of the first four days of the month recorded highs reaching the century mark.[31] The highest temperature ever recorded in the city was 106 °F (41 °C) on July 14, 1980.[30]

In the 1991–2020 climate normals, the daily average temperature in January is 53.2 °F (11.8 °C). Freezing temperatures occur an average of 11 days per winter, with the average first and last dates for a freeze being December 12 and February 14, giving Pensacola an average growing season of 301 days. However, the relatively recent winter season of 2018-19 did not record a freeze, the median first and last freeze dates are earlier and later than the averages of December 12 and February 14, and the median number of freezes per season is 11 or fewer.[32] The mean coldest temperature reached in a given winter season is about 24 °F (−4.4 °C); although the median is slightly higher, at no colder than 25 °F (−3.9 °C) most years, placing Pensacola in USDA zone 9b. Temperatures below 20 °F (−6.7 °C) are very rare, and last occurred on January 8, 2015,[33] when a low of 19 °F (−7.2 °C) was seen.[34] The lowest temperature ever recorded in the city was 5 °F (−15 °C) on January 21, 1985.[30]

Snow is rare in Pensacola, but does occasionally fall. The most recent snowfall event occurred December 9, 2017,[35] and the snow event previous to it occurred on February 12, 2010.[36] The city receives 68.31 in (1,740 mm) of precipitation per year, with a slightly more rainy season in the summer. The rainiest month is July, with 7.89 in (200 mm), with May being the driest month at 3.90 in (99 mm).[30] In June 2012 over one foot (300 mm) of rain fell on Pensacola and adjacent areas, leading to widespread flooding.[37] On April 29, 2014, Pensacola was drenched by at least 20 inches of rain within a 24-hour period, causing the worst flooding in 30 years.[38]

The city suffered a major blow on February 23, 2016, when a large EF3 wedge tornado hit the northwest part of Pensacola, causing major damage and several injuries.[39]

| Climate data for Pensacola, Florida (Pensacola Int'l), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1879–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

84 (29) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

97 (36) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.9 (23.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

82.5 (28.1) |

85.2 (29.6) |

92.6 (33.7) |

95.7 (35.4) |

97.0 (36.1) |

96.2 (35.7) |

94.8 (34.9) |

88.9 (31.6) |

82.3 (27.9) |

77.6 (25.3) |

98.4 (36.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 62.7 (17.1) |

66.4 (19.1) |

72.0 (22.2) |

77.6 (25.3) |

85.1 (29.5) |

90.0 (32.2) |

91.6 (33.1) |

91.0 (32.8) |

88.5 (31.4) |

81.1 (27.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

65.1 (18.4) |

78.6 (25.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.2 (11.8) |

56.8 (13.8) |

62.3 (16.8) |

68.3 (20.2) |

76.0 (24.4) |

81.7 (27.6) |

83.5 (28.6) |

83.0 (28.3) |

80.0 (26.7) |

71.3 (21.8) |

61.4 (16.3) |

55.5 (13.1) |

69.4 (20.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 43.7 (6.5) |

47.2 (8.4) |

52.7 (11.5) |

59.0 (15.0) |

66.9 (19.4) |

73.5 (23.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

75.0 (23.9) |

71.5 (21.9) |

61.6 (16.4) |

51.0 (10.6) |

45.9 (7.7) |

60.3 (15.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 25.7 (−3.5) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

35.1 (1.7) |

44.0 (6.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

66.7 (19.3) |

70.4 (21.3) |

69.2 (20.7) |

60.3 (15.7) |

44.6 (7.0) |

34.1 (1.2) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 5 (−15) |

7 (−14) |

22 (−6) |

33 (1) |

44 (7) |

55 (13) |

61 (16) |

60 (16) |

43 (6) |

32 (0) |

22 (−6) |

11 (−12) |

5 (−15) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.03 (128) |

4.77 (121) |

5.25 (133) |

5.52 (140) |

3.90 (99) |

7.32 (186) |

7.89 (200) |

7.50 (191) |

6.61 (168) |

4.70 (119) |

4.42 (112) |

5.40 (137) |

68.31 (1,735) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.6 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 12.0 | 15.3 | 14.7 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 9.5 | 115.3 |

| Source: NOAA[40][32] | |||||||||||||

Hurricanes

Pensacola's location on the Florida Panhandle makes it vulnerable to hurricanes. Hurricanes which have made landfall at or near Pensacola since the late 20th century include Eloise (1975), Frederic (1979), Juan (1985), Erin (1995), Opal (1995), Georges (1998), Ivan (2004), Dennis (2005), and Sally (2020). In July 2005, Hurricane Dennis made landfall just east of the city, sparing it the damage received from Ivan the year before. However, hurricane and near-hurricane-force winds were recorded in downtown, causing moderate damage.

Pensacola received only a glancing blow from Hurricane Katrina in 2005, resulting in light to moderate damage reported in the area. The aftermath of the extensive damage from Katrina was a dramatic reduction in tourism coming from Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

Hurricane Ivan

On September 16, 2004,[41] Pensacola and several surrounding areas were devastated by Hurricane Ivan. Pensacola was on the eastern side of the eyewall, which sent a large storm surge into Escambia Bay; this destroyed most of the I-10 Escambia Bay Bridge. The storm knocked 58 spans off the eastbound and westbound bridges and misaligned another 66 spans, forcing the bridge to close to traffic in both directions.[42] The surge also destroyed the fishing bridge that spanned Pensacola Bay alongside the Phillip Beale Memorial Bridge, locally known as the Three Mile Bridge.[43]

Over $6 billion in damage occurred in the metro area and more than 10,000 homes were destroyed, with another 27,000 heavily damaged. 105,000 households in Northwest Florida were impacted in some way by the storm, and 4,300 businesses in the area permanently closed as a result of Hurricane Ivan.[44] NASA created a comparison image to illustrate the massive damage. This widespread destruction of property caused a temporary lack of affordable housing in the Pensacola real estate market, and Hurricane Dennis and Hurricane Katrina contributed to a general scarcity of construction labor and resources along the Gulf Coast.[44]

Hurricane Sally

In September 2020, Pensacola suffered heavy damage by Hurricane Sally. Damages in Escambia County were estimated by local officials at $29 million. Downtown Pensacola was flooded.[45]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,164 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,876 | 32.9% | |

| 1870 | 3,347 | 16.4% | |

| 1880 | 6,845 | 104.5% | |

| 1890 | 11,750 | 71.7% | |

| 1900 | 17,747 | 51.0% | |

| 1910 | 22,982 | 29.5% | |

| 1920 | 31,035 | 35.0% | |

| 1930 | 31,579 | 1.8% | |

| 1940 | 37,449 | 18.6% | |

| 1950 | 43,479 | 16.1% | |

| 1960 | 56,752 | 30.5% | |

| 1970 | 59,507 | 4.9% | |

| 1980 | 57,619 | −3.2% | |

| 1990 | 58,165 | 0.9% | |

| 2000 | 56,255 | −3.3% | |

| 2010 | 51,923 | −7.7% | |

| 2020 | 54,312 | 4.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[46] | |||

Pensacola's first appearance in the U.S. Census dataset was in 1850, with a total recorded population of 2,164.[47] Pensacola was Florida's largest city in 1860 with the population of 2,876.[48]

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[49] | Pop 2020[50] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 33,383 | 35,105 | 64.29% | 64.64% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 14,420 | 12,054 | 27.77% | 22.19% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 269 | 194 | 0.52% | 0.36% |

| Asian (NH) | 1,024 | 1,290 | 1.97% | 2.38% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 62 | 43 | 0.12% | 0.08% |

| Some other race (NH) | 58 | 269 | 0.11% | 0.50% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 996 | 2,519 | 1.92% | 4.64% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,711 | 2,838 | 3.30% | 5.23% |

| Total | 51,923 | 54,312 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the census of 2020, there were 509,905 people in the Pensacola metropolitan area (MSA).

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 54,312 people, 22,926 households, and 12,247 families residing in the city.[51]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 51,923 people, 23,768 households, and 13,646 families residing in the city.[52]

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 448,991 people in the Pensacola-Ferry Pass-Brent, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). The population density was 2,303.5 inhabitants per square mile (889.4/km2). There were 26,848 housing units at an average density of 1,189.4 per square mile (459.2/km2).

In 2010, there were 24,524 households, out of which 24.6% had children living with them, 39.7% were married couples living together, 16.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.2% were non-families. 32.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.92.

In 2010, the median income for a household in the city was $34,779, and the median income for a family was $42,868. Males had a median income of $32,258 versus $23,582 for females. The per capita income for the city was $30,556. About 12.7% of families and 16.3%[53] of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.2% of those under age 18 and 9.2% of those age 65 or over.

Religion

Out of the total population of Pensacola in 2010, 45.9% identified with a religion, slightly lower than the national average of 48.3%.[54] Over 48% of Pensacola residents who practice a religion identify as Baptists (22.1%).[54] Other Christian denominations include Roman Catholics (9.2% of city residents), Pentecostal (3.8%), Methodist (3.8%), Episcopal (1.1%), Presbyterian (1.1%), and Orthodox (0.3%).[54]

As of 2010, Pensacola is home to a small (0.2% of city residents)[54] but significant Jewish community, whose roots date mostly to German Jewish immigrants of the mid-to-late 19th century. There were also Sephardic Jewish migrants from other areas of the South, and immigrants from other areas of Europe. The first Florida chapter of B'nai Brith was founded downtown in 1874, as well as the first temple, Beth-El, in 1876. Apart from the Reform Beth-El, Pensacola is also served by the Conservative B'nai Israel Synagogue.[55] Paula Ackerman, the first woman who performed rabbinical functions in the United States, was a Pensacola native and led services at Beth-El.

Economy

Military

The city has been referred to as "The Cradle of Naval Aviation".[56] Naval Air Station Pensacola (NASP) was the first Naval Air Station commissioned by the U.S. Navy in 1914. Tens of thousands naval aviators have received their training there, including John H. Glenn, USMC, who became the first American to orbit the Earth in 1962, and Neil Armstrong, who became the first man to set foot on the Moon in 1969.[57] The Navy's Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels, is stationed there.

The National Museum of Naval Aviation is located on the Naval Air Station and is free to the public. The museum cares for and exhibits hundreds of vintage Naval Aviation aircraft and preserves the history of Naval Aviation through displays, symposiums, IMAX movies and tours.

Corry Station Naval Technical Training Center serves as an annex for the main base and the center for Information Dominance. CWO3 Gary R. Schuetz Memorial Health Clinic is at Corry Station, Naval Hospital Pensacola, as is the main Navy Exchange and Defense Commissary Agency commissary complex for both Corry Station and NAS Pensacola. The Army National Guard B Troop 1-153 Cavalry, Bravo Company 146th Expeditionary Signal Battalion is stationed in Pensacola.

Tourism

Pensacola is home to a number of annual festivals, events, historic tours, and landmarks. The Pensacola Seafood Festival and the Pensacola Crawfish Festival have been held for nearly 30 years in the city's historic downtown. The Great Gulfcoast Arts Festival is held annually in November in Seville Square, and often draws more than 200 regional and international artists. The Children's Art Festival, also held in Seville Square, displays art by local schoolchildren. Pensacon is a comic convention held each February, with nearly 25,000 attendees from around the world. The Pensacola Interstate Fair is held each fall.[58]

Scuba diving and deep sea fishing are a large part of Pensacola's tourism industry. The USS Oriskany was purposefully sunk in 2004 to create an artificial reef off the shores of Pensacola.[59]

There are several walking tours of restored 18th-century-era neighborhoods in Pensacola.

Pensacola is the site of the Vietnam Veterans' Wall South. There are a number of historical military installations from the Civil War, including Fort Barrancas. Fort Pickens served as a temporary prison for Geronimo. Other military landmarks include the National Naval Aviation Museum and Pensacola Lighthouse at NAS Pensacola.

The city's convention and visitors' bureau, Visit Pensacola,[60] is overseen by the Greater Pensacola Chamber.[61]

Top employers

| Rank | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Navy Federal Credit Union | 7,723 |

| 2 | Baptist Health Care | 6,633 |

| 3 | Sacred Heart Health Systems | 4,820 |

| 4 | Florida Power And Light | 1,774 |

| 5 | West Florida Healthcare | 1,200 |

| 6 | Ascend Performance Materials | 888 |

| 7 | Alorica (fka West Corporation) | 800 |

| 8 | Innisfree Hotels | 750 |

| 9 | Santa Rosa Medical Center | 521 |

| 10 | Medical Center Clinic | 500 |

Arts and culture

The arts and theatre

There are a number of performance venues in the Pensacola area, including the Pensacola Bay Center (formerly the Pensacola Civic Center),[63] often used for big-ticket events, and the Saenger Theater, used for performances and mid-level events. Other theatres used for live performances, plays, and musicals include the Pensacola Little Theatre, Pensacola State College, University of West Florida, Vinyl Music Hall, and Loblolly Theatre. Pensacola is also home to the Pensacola Opera, Pensacola Children's Chorus, Pensacola Symphony Orchestra, Pensacola Civic Band, Pensacola Bay Concert Band, and the Choral Society of Pensacola, as well as Ballet Pensacola. There is also the Palafox Place entertainment district.

Architecture

Pensacola does not have a prominent skyline, but has several low-rise buildings. The tallest is the 15-floor Crowne Plaza Grand Hotel, at 146 ft (45 m). Other tall buildings include the Scenic Apartments (98 feet; 30 m), SunTrust Tower (96 feet; 29 m), Seville Tower (88 feet; 27 m), and the AT&T Building (76 feet; 23 m).

Historic buildings in Pensacola include the First National Bank Building.

Museums

Pelican Drop

The Pelican Drop was a New Year's Eve celebration that took place each year in downtown Pensacola. At the ceremony, an aluminum pelican, the city's mascot, was dropped instead of the typical New Year's ball. The event included live music and fireworks. From 2008 to 2018, The Pelican Drop was a significant attraction in the area, drawing in crowds of up to 50,000 local residents and visitors, making it one of the largest events of its kind in the Central Time Zone. In 2014, the event was named as one of the Top 20 Events in the Southeast by the Southeast Tourism Society.[64]

History

The First Pelican Drop New Year's Celebration took place in 2008. The Pensacola News Journal released an article stating that the Pensacola Community Redevelopment Agency was planning a new kind of New Year's Eve celebration, to be held at the Plaza Ferdinand VII and broadcast live on WEAR-TV; beginning with the 2017 celebration, events were carried in simulcast on WEAR's website. Almost 45,000 people showed up for the event, including residents of Mobile, Alabama (which hosts its own competing drop, a Moon Pie), Milton, Florida, Navarre, Florida, and Destin, Florida.[65]

In December 2019, organizers announced that the Pelican Drop had been canceled due to financial issues and the burden the event had caused on local police and public services. A smaller fireworks display, which does not require the same amount of traffic disruption, would be held instead.[66]

The pelican was made and designed by Emmett Andrews LLC.[67] Made of polished aluminum and decorated with over 2,000 lights, the bird had a 17-foot (5.2 m) wingspan and is 12 ft (3.7 m) high.[64]

Sports

Notable sports teams in Penascola include:

| Team | Sport | League | Venue |

| Pensacola Ice Flyers | Ice hockey | SPHL | Pensacola Bay Center |

| Gulf Coast Riptide | American football | Women's Spring Football League | Escambia High School |

| Pensacola Blue Wahoos | Baseball | Southern League (AA) | Pensacola Bayfront Stadium |

| Pensacola FC | Soccer | Gulf Coast Premier League | Ashton Brosnaham Stadium |

| West Florida Argonauts | Baseball, Basketball, American Football | NCAA Division II Gulf South Conference | University of West Florida |

| Pensacola Roller Gurlz | Flat Track Roller Derby | Women's Flat Track Derby Association | Dreamland Skate Center |

Previously, the Pensacola Pelicans was an independent league baseball team that played at Jim Spooner Field from 2002 to 2010.

The city hosted professional golf tournaments such as the Pensacola Open (PGA Tour, 1958–1988), the Pensacola Ladies Invitational (LPGA Tour, 1965–1968) and Pensacola Classic (Nike Tour, 1990–1995).

America's Cup team American Magic call Pensecola their home port until the 2024 America's Cup commences.

The Five Flags Speedway is a half-mile paved racetrack that opened in 1953. It hosts the Snowball Derby stock car race every December since 1968. It has also hosted rounds of the NASCAR Grand National (now NASCAR Cup Series), Superstar Racing Experience, NASCAR Southeast Series, ARCA Racing Series, ARCA Menards Series East, ASA National Tour, CARS Pro Cup Series and Southern Super Series.

Parks and recreation

- Gulf Islands National Seashore

- Big Lagoon State Park - approximately 10 mi (16 km) southwest of Pensacola on Gulf Beach Highway[68]

- Perdido Key State Park - located on a barrier island 15 mi (24 km) southwest of Pensacola, off S.R. 292[69]

- Tarkiln Bayou Preserve State Park - 10 mi (16 km) southwest of Pensacola,[70]

- Pensacola Bayfront Stadium - a multi-use park in Pensacola[71]

- Plaza Ferdinand VII

- Bayview Park[72]

- Miraflores Park[73]

Government

| Council Members | |

| District | Council member |

|---|---|

| 1 | Jennifer Brahier |

| 2 | Charles Bare |

| 3 | Casey Jones |

| 4 | Jared Moore |

| 5 | Teniade Broughton |

| 6 | Allison Patton |

| 7 | Delarian Wiggins |

The city of Pensacola utilizes a strong mayor-council form of government, which was adopted in 2011 after citizens voted in 2009 to approve a new city charter. An elected mayor serves as the chief executive of the city government, while a seven-member city council serves as the city's governing body. A council president is selected by the council from its members, along with a vice president.

City voters approved a charter amendment on June 11, 2013, which eliminated the then-nine member council's two at-large seats; one seat was phased out in November 2014, and the other expired in November 2016. Two additional charter amendments were approved on November 4, 2014, which made the position of mayor subject to recall and provided the city council with the authority to hire staff. The current city hall was opened in 1986.

Politics

After the Civil War, Pensacola, like the rest of the South, was controlled by Republicans during the Reconstruction era (1865-1877). The Republican government had numerous African American politicians, including several county commissioners, city aldermen, constables, state representatives, and even one African American mayor—Salvador Pons. However, with the 1884 election of native Pensacolian and former Confederate general Edward Perry, a dramatic shift occurred. Perry, a Democrat who actually lost the Escambia County vote during the statewide election, acted to dissolve the Republican city government of Pensacola and in 1885 replaced this government with hand-picked successors, including railroad magnate William D. Chipley. The only African American to remain in city government was George Washington Witherspoon, a pastor with the African Methodist Episcopal Church who was previously a Republican and switched parties to the Democrats. Following Governor Perry's dissolution of the Republican government, the city remained Democratic for more than a century after the Civil War with no African Americans serving in an elected capacity for nearly a century.

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 51.5% 18,181 | 46.4% 16,356 | 2.1% 751 |

| 2016 | 46.7% 15,183 | 47.3% 15,386 | 6.1% 1,974 |

This changed in 1994, when Republican attorney Joe Scarborough defeated Vince Whibbs, Jr., the son of popular former Democratic mayor Vince Whibbs, in a landslide to represent Florida's 1st congressional district, which is based in Pensacola. Republicans also swept all of the area's seats in the state legislature, the majority of which were held by Democrats. Since then, Republicans have dominated every level of government, although municipal elections are officially nonpartisan.

Regional representatives

Pensacola is currently represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by Matt Gaetz (R), in the state senate by Doug Broxson (R),[75] and in the state house by District 2 representative Alex Andrade (R).[76]

Education

The main campus of Pensacola State College is in the City of Pensacola. The University of West Florida (UWF) operates a campus in downtown Pensacola. Its main campus, located north of the city, has the largest library in the region, the John C. Pace Library. UWF is the largest post-secondary institution in the area.

Public primary and secondary schools in Pensacola are administered by the Escambia County School District. The district operates two high schools (Booker T. Washington and Pensacola) within the City of Pensacola. District-run high schools near the city include Escambia, J. M. Tate, and Pine Forest. Other public schools in the city include A.K. Suter Elementary, Cordova Park Elementary, J.H. Workman Middle, N.B. Cook Elementary, O.J. Semmes Elementary, and Scenic Heights Elementary. The district also operates one magnet high school (West Florida High School of Advanced Technology) near the city.

Several private schools operate within or near the city: East Hill Academy, East Hill Christian School, Episcopal Day School of Christ Church, Pensacola Catholic High School, Pensacola Christian Academy, Sacred Heart Cathedral School, Saint John the Evangelist Catholic School, Saint Paul Catholic School, Little Flower Catholic School, and Seville Bayside Montessori. The campus of Pensacola Christian College is near the city.

Media

The largest daily newspaper in the area is the Pensacola News Journal, with offices on Romana Street in downtown; the News Journal is owned by the Gannett Company. There is an alternative weekly newspaper, Inweekly.

Pensacola is home to WEAR-TV, the ABC affiliate for Pensacola, Navarre, Fort Walton Beach, and Mobile, Alabama, and WSRE-TV, the local PBS member station, which is operated by Pensacola State College. Other television stations in the market include WALA-TV, the Fox affiliate; WKRG, the CBS affiliate; and WPMI, the NBC affiliate, which are all located in Mobile. Cable service in the city is provided by Cox Communications and AT&T U-Verse. WUWF is the area's NPR affiliate and is based at the University of West Florida. WPCS (FM) is broadcast from the Pensacola Christian College campus, where the nationwide Rejoice Radio Network maintains its studio.[77]

Pensacola Magazine, the city's monthly glossy magazine, and Northwest Florida's Business Climate, the only business magazine devoted to the region, are published locally. The News Journal also publishes Home & Garden Weekly magazine as well as the monthly Bella, devoted to women.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Aviation

Major air traffic in the Pensacola and greater northwest Florida area is handled by Pensacola International Airport. Pensacola International is the largest airport in Northwest Florida by passenger count and is the second busiest in all of North Florida, just behind Jacksonville. As of August 2023, airlines serving Pensacola International Airport are American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Frontier Airlines, Silver Airways, Southwest Airlines, Spirit Airlines, and United Airlines.[78]

Railroads

Pensacola was first connected by rail with Montgomery, Alabama, via the Alabama and Florida Railroad, completed in 1861 just before the start of the Civil War. During the war, most of the rails between Pensacola and the Alabama state line were removed to construct other railroad lines urgently needed elsewhere in the Confederacy. The line to Pensacola was not rebuilt until 1868, and was acquired by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad in 1880. In 1882, the Pensacola and Atlantic Railroad was completed from Pensacola to Chattahoochee, Florida, linking Pensacola with the rest of the state. This line was also acquired by the L&N.

By 1928, a number of short lines built northward from Pensacola to Kimbrough, Alabama, were acquired by the Frisco Railroad, giving it access to the port of Pensacola.[79][80] Some thirty years later, retired Frisco steam engine 1355 was donated to the city and stands in the median of Garden Street, near the site of the now-demolished Frisco passenger station.[81]

Frisco passenger service to Pensacola ended in 1955, and L&N passenger service, including the streamlined Gulf Wind, ended in 1971 with the advent of Amtrak. However, from early 1993 through August 2005 Pensacola was served by the tri-weekly Amtrak Sunset Limited, but service east of New Orleans to Jacksonville and Orlando was suspended due to damage to the rail line of CSX during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[82]

In the 21st century, freight service to and from Pensacola is provided by L&N successor CSX as well as Frisco successor Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway, a short line. On June 1, 2019, the newly formed Florida Gulf & Atlantic Railroad, a Class III railroad headquartered in Tallahassee, acquired the CSX main line from Pensacola to Baldwin, Florida, near Jacksonville, becoming the Panhandle's only east–west freight hauler. A news report on the new railroad in mid-2019 noted that Amtrak indicated that the Panhandle had a "near-zero chance" of seeing passenger service restored.[83] Pensacola and Tallahassee are the two largest metropolitan areas in Florida without any passenger rail service.

Major highways

Interstate 10

Interstate 10 Interstate 110

Interstate 110 U.S. Route 29

U.S. Route 29 U.S. Route 90 & U.S. Route 90 Alternate

U.S. Route 90 & U.S. Route 90 Alternate U.S. Route 98 & U.S. Route 98 Business

U.S. Route 98 & U.S. Route 98 Business State Road 289 Ninth Avenue

State Road 289 Ninth Avenue State Road 291 Davis Highway

State Road 291 Davis Highway State Road 292 Pace Boulevard

State Road 292 Pace Boulevard State Road 295 New Warrington Road, Farfield Drive

State Road 295 New Warrington Road, Farfield Drive State Road 296 Michigan Avenue, Beverly Parkway, Brent Lane, Bayou Boulevard, Perry Street

State Road 296 Michigan Avenue, Beverly Parkway, Brent Lane, Bayou Boulevard, Perry Street State Road 742 Creighton Road, Burgess Road

State Road 742 Creighton Road, Burgess Road State Road 750 Airport Boulevard

State Road 750 Airport Boulevard

Mass transit

The local bus service is the Escambia County Area Transit.[84] ECAT operates fixed route bus service and paratransit service. The ECAT system currently provides fixed-route bus service, as well as the seasonal Pensacola Beach trolley and University of West Florida on-campus trolley.[84] There is a website and an app for bus times called moovit.[85] The app can be downloaded from this site, which also shows the service area and lists the routes.[86]

Pensacola also has a ferry service owned by the National Park Service. It has stops in Downtown Pensacola, Pensacola Beach and Fort Pickens.

Bus

The city is served by Greyhound Bus and Greyhound Lines.[87]

Hospitals

Hospitals in Pensacola include Ascension Sacred Heart Hospital, Baptist Hospital, Encompass Health Rehabilitation Hospital, HCA Florida West Hospital, Select Specialty Hospital, and West Florida Hospital.[88]

Notable people

Bands from Pensacola

- Finite Automata, an industrial band

- This Bike is a Pipe Bomb, a folk-punk band

- Twothirtyeight, indie rock band

- Body Head Bangerz, hip hop group

- McAlyster, country music group

Sister cities

Pensacola's sister cities are:[89]

Chimbote, Peru

Chimbote, Peru Escazú, Costa Rica

Escazú, Costa Rica Gero, Japan

Gero, Japan Isla Mujeres, Mexico

Isla Mujeres, Mexico Horlivka, Ukraine

Horlivka, Ukraine Miraflores, Peru

Miraflores, Peru Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Kaohsiung, Taiwan Macharaviaya, Spain

Macharaviaya, Spain

See also

References

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- 1 2 "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Annual Estimares of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018 - United States - Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area, and for Puerto Rico - 2018 Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ↑ Worth, John E. "The Tristán de Luna Expedition, 1559-1561". uwf.edu. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016.

- ↑ Swanton, John Reed (2003). The Indian tribes of North America. Genealogical Publishing. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jane E. Dysart, "Another Road to Disappearance: Assimilation of Creek Indians in Pensacola, Florida during the Nineteenth Century", The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 1 (July 1982), pp. 37–48, Published by: Florida Historical Society, Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30146156 Archived 2019-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 26 June 2014

- ↑ Dean R. Snow, Archaeology of Native North America (2010), New York: Prentice-Hall. pp. 248–249

- 1 2 3 ""History" (Luna colony at Ochuse/Pensacola)". MyFlorida.com. State of Florida, Office of Cultural & Historical Programs. 2007. Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ↑ Davis, Jack E. (2017). The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea. Liveright. ISBN 978-0871408662.

- 1 2 3 4 John E. Worth, The Tristán de Luna Expedition, 1559–1561, http://uwf.edu/jworth/spanfla_luna.htm Archived 2016-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson, Jane. "Santa Rosa Island - a History (Part 1)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 14, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Pinson, Steve. "The Tristan de Luna Expedition". Pensacola Archeology Lab. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Floripedia: Pensacola, Florida". University of South Florida. 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa". University of West Florida. 2003. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ↑ Gene Allen Smith, Texas Christian University, Sanctuary in the Spanish Empire: An African American officer earns freedom in Florida, National Park Service, archived from the original on January 10, 2021, retrieved April 5, 2018

- ↑ John Richard Alden (1957). The South in the Revolution, 1763–1789. Louisiana State University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8071-0013-4.

- ↑ Coker, William S; Shofner, Jerrell H.; Morris, Joan Perry; Malone, Myrtle Davidson (1991). Florida from the Beginning to 1992 : a Columbus Jubilee Commemorative. Houston: Pioneer Publications. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ↑ Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763-1783 By James W. Raab

- 1 2 "St. Michael's Cemetery Foundation of Pensacola, Inc". Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Museum of Florida History". www.museumoffloridahistory.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ↑ Sheppard, Jonathan C. (2012). By the noble daring of her sons : the Florida Brigade of the Army of Tennessee. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780817317072.

- ↑ "A century ago, martial law shuttered Pensacola as streetcars were bombed, militia took over city". The Pulse. April 7, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ↑ Flynt, Wayne (1965). "Pensacola Labor Problems and Political Radicalism, 1908". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 43 (4): 315–332. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30140132.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Pensacola city, Florida". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Story Map Series". noaa.maps.arcgis.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ↑ "STORM2K - South Florida Cold Snap Is Overhyped - Much Warmer". Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Pensacola, Florida Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Monthly Averages for Pensacola, Fla". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ↑ "History for Pensacola, Florida on Wednesday, June 1, 2011". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- 1 2 "Station: Pensacola RGNL AP, FL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ↑ Team, National Weather Service Corporate Image Web. "National Weather Service Climate". w2.weather.gov. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "History for Pensacola, Florida on Tuesday, January 7, 2014". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Past Weather in Pensacola, Florida USA - December 2017?". CustomWeather Monitor. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ "What's with these snowstorms?". Christian Science Monitor. February 13, 2010. Archived from the original on November 9, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Floods, Water Rescues Along Gulf Coast". weather.com. June 10, 2012. Archived from the original on December 25, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ↑ "'Life-Threatening' Flooding Submerges Pensacola, Florida". NBC News. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Tornado aftermath: 300+ homes destroyed, damaged". Pensacola News Journal. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ↑ "Powerful Hurricane Ivan Slams the Central Gulf Coast as a Category 3 Hurricane". National Weather Service (September 16, 2004). United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ↑ "Repairing Florida's Escambia Bay Bridge". ACP Construction. Archived from the original on January 27, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Bridge Replacement over Escambia Bay". Florida Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- 1 2 "Ivan Turned Gulf Coast Real Estate Upside Down". WUWF. September 23, 2014. Archived from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sally a 'major disaster' but no individual assistance coming without public's help". Pensacola News Journal. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "1850 Census of Population: Florida" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ↑ "1860 Census of Population: Florida" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ↑ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Pensacola city, Florida". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ↑ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Pensacola city, Florida". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ↑ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Pensacola city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Pensacola city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Pensacola (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Pensacola, Florida - Religion". Bestplaces.net. Archived from the original on December 30, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ↑ "借金天国". Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "About". Commander, Navy Installations Command. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Naval Air Station Pensacola Base Guide". Military.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ↑ "The Pensacola Interstate Fair". Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ↑ Edlund, Martin (May 6, 2006). "You Sank My Tourist Attraction!". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Official Tourism Website of Pensacola, Florida". Archived from the original on August 2, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Greater Pensacola Chamber - Home". Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "TOP EMPLOYERS" (PDF). floridawesteda.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ↑ "Civic Center renamed "Pensacola Bay Center" | Pensacola Digest". Archived from the original on October 20, 2012.

- 1 2 Scheurich, Hal (December 31, 2010). "Pensy Pelican readies for New Year drop". Fox10 TV. WALA-TV. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Visit South No Longer Exists But Travel Sweepstakes Are Still Here". Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ↑ Beninate, Renee (December 30, 2019). "Fireworks, but no Pelican Drop, for this year's NYE celebration in downtown Pensacola". WEAR. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ↑ Ross, Rebecca (December 7, 2008). "Build-a-bird". Pensacola News Journal. Pensacola, FL. pp. E1. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Big Lagoon State Park Unit Management Plan" (PDF). Division of Recreation and Parks. STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION. October 13, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Perdido Key State Park". Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Tarkiln Bayou Preserve State Park". Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ↑ "HUNTER AMPHITHEATRE". Joe DeReuil Associates, LLC. 2007. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Bayview Park". City of Pensacola. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Miraflores Park". City of Pensacola. Archived from the original on August 14, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Dave's Redistricting". Archived from the original on February 28, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Senator Broxson - The Florida Senate". www.flsenate.gov. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ↑ "Florida House of Representatives - Robert Alexander "Alex" Andrade - 2018 - 2020 (Speaker Oliva )". www.myfloridahouse.gov. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ↑ "About Us". WPCS Rejoice Radio. Pensacola, FL: Pensacola Christian College. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Airlines". Pensacola International Airport. 2019. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ↑ "Frisco Will Spend $2,500,000 in Rehabilitating Pensacola Road" (PDF). The Frisco Employes' Magazine. III (4): 8–9. January 1926. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ↑ "The Frisco Meets the Gulf" (PDF). The Frisco Employes' Magazine. V (11): 14–21. August 1928. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ↑ "History". West Florida Railroad Museum. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ↑ "Amtrak - Error". Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ Flanigan, Tom (July 29, 2019). "Florida Gulf And Atlantic Assumes Ownership of North Florida Rail Line". WFSU.org. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- 1 2 "Mass Transit/ECAT Authority". Escambia County, Florida. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Trip Planner". ECAT. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Moovit App for ECAT". ECAT. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Pensacola station". Greyhound.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ↑ "List of Facilities". Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ↑ "How to help Pensacola's Japanese Sister City devastated by flooding". Pensacola News Journal. July 25, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2021.