| Wayang | |

|---|---|

| |

| Types | Traditional puppet theatre |

| Ancestor arts | Javanese people |

| Originating culture | Indonesia |

| Originating era | Hindu - Buddhist civilisations |

| Wayang Puppet Theatre | |

|---|---|

Wayang kulit performance by the famous Indonesian dalang (puppet master) Manteb Soedharsono, with the story "Gathutkaca Winisuda", in Bentara Budaya Jakarta, Indonesia, on 31 July 2010 | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Criteria | Performing arts, Traditional craftsmanship |

| Reference | 063 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2008 (3rd session) |

| List | Representative List |

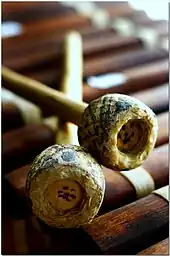

Wayang Kulit (the leather shadow puppet), Wayang Klithik (the flat wooden puppet), Wayang Golek (the three-dimensional wooden puppet) | |

| This article is a part of the series on |

| Indonesian mythology and folklore |

|---|

|

|

|

Wayang, also known as wajang (Javanese: ꦮꦪꦁ, romanized: wayang), is a traditional form of puppet theatre play originating from the Indonesian island of Java.[1][2][3] Wayang refers to the entire dramatic show. Sometimes the leather puppet itself is referred to as wayang.[4] Performances of wayang puppet theatre are accompanied by a gamelan orchestra in Java, and by gender wayang in Bali. The dramatic stories depict mythologies, such as episodes from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, as well as local adaptations of cultural legends.[2][5][6] Traditionally, a wayang is played out in a ritualized midnight-to-dawn show by a dalang, an artist and spiritual leader; people watch the show from both sides of the screen.[2][5]

Wayang performances are still very popular among Indonesians, especially in the islands of Java and Bali. Wayang performances are usually held at certain rituals, certain ceremonies, certain events, and even tourist attractions. In ritual contexts, puppet shows are used for prayer rituals (held in temples in Bali),[7] ruwatan ritual (cleansing Sukerto children from bad luck),[8] and sedekah bumi ritual (thanksgiving to God for the abundant crops).[9] In the context of ceremonies, usually it is used to celebrate mantenan (Javanese wedding ceremony) and sunatan (circumcision ceremony). In events, it is used to celebrate Independence Day, the anniversaries of municipalities and companies, birthdays, commemorating certain days, and many more. Even in the modern era with the development of tourism activities, wayang puppet shows are used as cultural tourism attractions.[10]

Wayang traditions include acting, singing, music, drama, literature, painting, sculpture, carving, and symbolic arts. The traditions, which have continued to develop over more than a thousand years, are also a medium for information, preaching, education, philosophical understanding, and entertainment.[11]

UNESCO designated wayang – the flat leather shadow puppet (wayang kulit), the flat wooden puppet (wayang klitik), and the three-dimensional wooden puppet (wayang golek) theatre, as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on 7 November 2003. In return for the acknowledgment, UNESCO required Indonesians to preserve the tradition.[12]

Etymology

The term wayang is the Javanese word for 'shadow'[3][13] or 'imagination'. The word's equivalent in Indonesian is bayang. In modern daily Javanese and Indonesian vocabulary, wayang can refer to the puppet itself or the whole puppet theatre performance.

History

Wayang is the traditional puppet theatre of Indonesia.[14][2][5] It is an ancient form of storytelling known for its elaborate puppets and complex musical styles.[15] The earliest evidence of wayang comes from medieval-era texts and archeological sites dating from late 1st millennium CE. There are four theories concerning where wayang originated (indigenous to Java; Java–India; India; and China), but of these, two are more favored: Java and India.

Regardless of its origins, states Brandon, wayang developed and matured into a Javanese phenomenon. There is no true contemporary puppet shadow artwork in either China or India that has the sophistication, depth, and creativity expressed in wayang in Java, Indonesia.[16]

Indigenous origin in Java

According to academic James R. Brandon, the puppets of wayang are native to Java. He states wayang is closely related to Javanese social culture and religious life, and presents parallel developments from ancient Indonesian culture, such as gamelan, the monetary system, metric forms, batik, astronomy, wet rice field agriculture, and government administration. He asserts that wayang was not derived from any other type of shadow puppetry of mainland Asia, but was an indigenous creation of the Javanese. Indian puppets differ from wayang, and all wayang technical terms are Javanese, not Sanskrit. Similarly, some of the other technical terms used in the wayang kulit found in Java and Bali are based on local languages, even when the play overlaps with Buddhist or Hindu mythologies.[16]

G. A. J. Hazeu also says that wayang came from Java. The puppet structure, puppeteering techniques, and storytelling voices, language, and expressions are all composed according to old traditions. The technical design, the style, and the composition of the Javanese plays grew from the worship of ancestors.

Kats argues that the technical terms come from Java and that wayang was born without the help of India. Before the 9th century, it belonged to the Javanese. It was closely related to religious practices, such as incense and night / wandering spirits. Panakawan uses a Javanese name, different from the Indian heroes.

Kruyt argues that wayang originated from shamanism, and makes comparisons with ancient archipelago ceremonial forms which aim to contact the spirit world by presenting religious poetry praising the greatness of the soul.

Origin in India

Hinduism and Buddhism arrived on the Indonesian islands in the early centuries of the 1st millennium, and along with theology, the peoples of Indonesia and Indian subcontinent exchanged culture, architecture, and traded goods.[16][17][6] Puppet arts and dramatic plays have been documented in ancient Indian texts, dated to the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE and the early centuries of the Common Era.[18] Further, the eastern coastal region of India (Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu), which most interacted with Indonesian islands, has had traditions of intricate, leather-based puppet arts called tholu bommalata, tholpavakoothu, and rabana chhaya, which share many elements with wayang.[2][19]

Some characters such as the Vidusaka in Sanskrit drama and Semar in wayang are very similar. Indian mythologies and characters from the Hindu epics feature in many major wayang plays, which suggests possible Indian origins, or at least an influence in the pre-Islamic period of Indonesian history.[16] Jivan Pani states that wayang developed from two art forms from Odisha in eastern India: the Ravana Chhaya puppet theatre and the Chhau dance.[20]

Records

The oldest known record concerning wayang is from the 9th century. Old Javanese (Kawi) inscriptions called Jaha Inscriptions, dating from around 840 CE and issued by Maharaja Sri Lokapala from the Mataram Kingdom in Central Java, mention three sorts of performers: atapukan (lit. 'mask dance show'), aringgit (lit. 'wayang puppet show'), and abanwal / abanol (lit. 'joke art'). Ringgit is described in an 11th-century Javanese poem as a leather shadow figure.

In 903 CE, the Mantyasih inscription (Balitung charter) was created by King Balitung of the Sanjaya dynasty of the Ancient Mataram Kingdom. They state, "Si Galigi Mawayang Buat Hyang Macarita Bimma Ya Kumara", which means 'Galigi held a puppet show for gods by taking the story of Bima Kumara'.[21] It seems certain features of traditional puppet theatre have survived from that time. Galigi was an itinerant performer who was requested to perform for a special royal occasion. At that event he performed a story about the hero Bhima from the Mahabharata.

Mpu Kanwa, the poet of Airlangga's court of the Kahuripan kingdom, writes in 1035 CE in his kakawin (narrative poem) Arjunawiwaha, "santoṣâhĕlĕtan kĕlir sira sakêng sang hyang Jagatkāraṇa", which means, "He is steadfast and just a wayang screen away from the 'Mover of the World'." As kĕlir is the Javanese word for the wayang screen, the verse eloquently comparing actual life to a wayang performance where the almighty Jagatkāraṇa (the mover of the world) as the ultimate dalang (puppet master) is just a thin screen away from mortals. This reference to wayang as shadow plays suggested that wayang performance was already familiar in Airlangga's court and wayang tradition had been established in Java, perhaps even earlier. An inscription from this period also mentions some occupations as awayang and aringgit.[22]

Wayang kulit is a unique form of theatre employing light and shadow. The puppets are crafted from buffalo hide and mounted on bamboo sticks. When held up behind a piece of white cloth, with an electric bulb or an oil lamp as the light source, shadows are cast on the screen. The plays are typically based on romantic tales and religious legends, especially adaptations of the classic Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Some of the plays are also based on local stories like Panji tales.[23]

- Wayang puppet theatre performances in Indonesia

Wayang kulit performance with gamelan accompaniment in the context of the appointment of the throne for Hamengkubuwono VIII's fifteen years in Yogyakarta, between 1900 and 1940

Wayang kulit performance with gamelan accompaniment in the context of the appointment of the throne for Hamengkubuwono VIII's fifteen years in Yogyakarta, between 1900 and 1940 A dalang (puppeteer) in a wayang golek (wooden puppet) performance, between 1880 and 1910

A dalang (puppeteer) in a wayang golek (wooden puppet) performance, between 1880 and 1910 Wayang Beber performance of the desa Gelaran at the home of Dr. Wahidin Soedirohoesodo at Yogyakarta; in the middle Dr. GAJ Hazeu, Dutch East Indies, in 1902

Wayang Beber performance of the desa Gelaran at the home of Dr. Wahidin Soedirohoesodo at Yogyakarta; in the middle Dr. GAJ Hazeu, Dutch East Indies, in 1902

Art form

Wayang kulit

Wayang kulit are without a doubt the best known of the Indonesian wayang. Kulit means 'skin', and refers to the leather construction of the puppets that are carefully chiselled with fine tools, supported with carefully shaped buffalo horn handles and control rods, and painted in beautiful hues, including gold. The stories are usually drawn from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[24]

There is a family of characters in Javanese wayang called punokawan; they are sometimes referred to as "clown-servants" because they normally are associated with the story's hero, and provide humorous and philosophical interludes. Semar is actually the god of love, who has consented to live on earth to help humans. He has three sons: Gareng (the eldest), Petruk (the middle), and Bagong (the youngest). These characters did not originate in the Hindu epics, but were added later.[25] They provide something akin to a political cabaret, dealing with gossip and contemporary affairs.

The puppet figures themselves vary from place to place. In Central Java, the city of Surakarta (Solo) and city of Yogyakarta have the best-known wayang traditions, and the most commonly imitated style of puppets. Regional styles of shadow puppets can also be found in Temanggung, West Java, Banyumas, Cirebon, Semarang, and East Java. Bali's wayang are more compact and naturalistic figures, and Lombok has figures representing real people. Often modern-world objects as bicycles, automobiles, airplanes and ships will be added for comic effect, but for the most part the traditional puppet designs have changed little in the last 300 years.

Historically, the performance consisted of shadows cast by an oil lamp onto a cotton screen. Today, the source of light used in wayang performance in Java is most often a halogen electric light, while Bali still uses the traditional firelight. Some modern forms of wayang such as wayang sandosa (from Bahasa Indonesia, since it uses the national language of Indonesian instead of Javanese) created in the Art Academy at Surakarta (STSI) employ theatrical spotlights, colored lights, contemporary music, and other innovations.

Making a wayang kulit figure that is suitable for a performance involves hand work that takes several weeks, with the artists working together in groups. They start from master models (typically on paper) which are traced out onto skin or parchment, providing the figures with an outline and with indications of any holes that will need to be cut (such as for the mouth or eyes). The figures are then smoothed, usually with a glass bottle, and primed. The structure is inspected and eventually the details are worked through. A further smoothing follows before individual painting, which is undertaken by yet another craftsman.

Finally, the movable parts (upper arms, lower arms with hands and the associated sticks for manipulation) mounted on the body, which has a central staff by which it is held. A crew makes up to ten figures at a time, typically completing that number over the course of a week. However, there is not strong continuing demand for the top skills of wayang craftspersons and the relatively few experts still skilled at the art sometimes find it difficult to earn a satisfactory income.[26]

The painting of less expensive puppets is handled expediently with a spray technique, using templates, and with a different person handling each color. Less expensive puppets, often sold to children during performances, are sometimes made on cardboard instead of leather.

- Some examples of wayang kulit figures (leather shadow puppet)

Princess Tari, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1934

Princess Tari, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1934

Wayang golek

Wayang golek (Sundanese: ᮝᮚᮀ ᮍᮧᮜᮦᮊ᮪) are three-dimensional wooden rod puppets that are operated from below by a wooden rod that runs through the body to the head, and by sticks connected to the hands. The construction of the puppets contributes to their versatility, expressiveness and aptitude for imitating human dance. wayang golek is mainly associated with the Sundanese culture of West Java. In Central Java, the wooden wayang is also known as wayang menak, which originated from Kudus, Central Java.

Little is known for certain about the history of wayang golek, but scholars have speculated that it most likely originated in China and arrived in Java sometime in the 17th century. Some of the oldest traditions of wayang golek are from the north coast of Java in what is called the Pasisir region. This is home to some of the oldest Muslim kingdoms in Java and it is likely that the wayang golek grew in popularity through telling the wayang menak stories of Amir Hamza, the uncle of Muhammad. These stories are still widely performed in Kabumen, Tegal, and Jepara as wayang golek menak, and in Cirebon, wayang golek cepak. Legends about the origins of the wayang golek attribute their invention to the Muslim saint Wali Sunan Kudus, who used the medium to proselytize Muslim values.

In the 18th century, the tradition moved into the mountainous region of Priangan, West Java, where it eventually was used to tell stories of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata in a tradition now called wayang golek purwa, which can be found in Bandung, Bogor and Jakarta. The adoption of Javanese Mataram kejawen culture by Sundanese aristocrats was probably the remnant of Mataram influence over the Priangan region during the expansive reign of Sultan Agung. While the main characters from the Ramayana and Mahabharata are similar to wayang kulit purwa versions from Central Java, some punakawan (servants or jesters) were rendered in Sundanese names and characteristics, such as Cepot or Astrajingga as Bagong, and Dawala or Udel as Petruk. Wayang golek purwa has become the most popular form of wayang golek today.

- Some examples of wayang golek figures (3D wooden puppet)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Ramawijaya, Indonesia in 2004

Ramawijaya, Indonesia in 2004 Gatot kaca, Indonesia in 2015

Gatot kaca, Indonesia in 2015 Kumbakarna, Indonesia before 1976

Kumbakarna, Indonesia before 1976 Dewi Drupadi, Indonesia before 1976

Dewi Drupadi, Indonesia before 1976

Wayang klitik

Wayang klitik or wayang karucil figures occupy a middle ground between the figures of wayang golek and wayang kulit. They are constructed similarly to wayang kulit figures, but from thin pieces of wood instead of leather, and, like wayang kulit figures, are used as shadow puppets. A further similarity is that they are the same smaller size as wayang kulit figures. However, wood is more subject to breakage than leather. During battle scenes, wayang klitik figures often sustain considerable damage, much to the amusement of the public, but in a country in which before 1970 there were no adequate glues available, breakage generally meant an expensive, newly made figure. On this basis the wayang klitik figures, which are to appear in plays where they have to endure battle scenes, have leather arms. The name of these figures is onomotopaeic, from the sound klitik-klitik that these figures make when worked by the dalang.

Wayang klitik figures come originally from eastern Java, where one still finds workshops turning them out. They are less costly to produce than wayang kulit figures.

The origin of the stories involved in these puppet plays comes from the kingdoms of eastern Java: Jenggala, Kediri and Majapahit. From Jenggala and Kediri come the stories of Raden Panji and Cindelaras, which tells of the adventures of a pair of village youngsters with their fighting cocks. The Damarwulan presents the stories of a hero from Majapahit. Damarwulan is a clever chap, who with courage, aptitude, intelligence and the assistance of his young lover Anjasmara makes a surprise attack on the neighboring kingdom and brings down Minakjinggo, an Adipati (viceroy) of Blambangan and mighty enemy of Majapahit's beautiful queen Sri Ratu Kencanawungu. As a reward, Damarwulan is married to Kencanawungu and becomes king of Majapahit; he also takes Lady Anjasmara as a second wife. This story is full of love affairs and battles and is very popular with the public. The dalang is liable to incorporate the latest local gossip and quarrels and work them into the play as comedy.

- Some examples of wayang klithik figures (flat wooden puppet)

Menak Jingga, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1953

Menak Jingga, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1953

Figure of Batara Guru

Figure of Batara Guru

Brathasena, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1986

Brathasena, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1986

Wayang beber

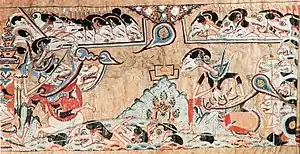

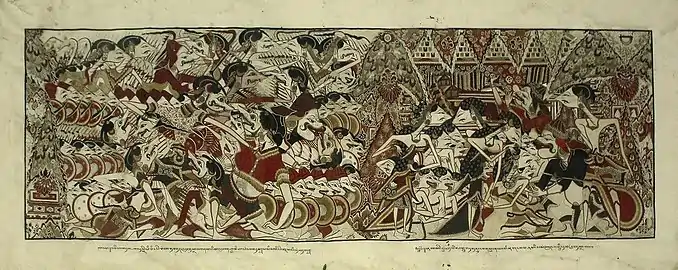

Wayang beber relies on scroll-painted presentations of the stories being told.[27] Wayang beber has strong similarities to narratives in the form of illustrated ballads that were common at annual fairs in medieval and early modern Europe. They have also been subject to the same fate—they have nearly vanished, although there are still some groups of artists who support wayang beber in places such as Surakarta (Solo) in Central Java.[28] Chinese visitors to Java during the 15th century described a storyteller who unrolled scrolls and told stories that made the audience laugh or cry. A few scrolls of images remain from those times, found today in museums. There are two sets, hand-painted on hand-made bark cloth, that are still owned by families who have inherited them from many generations ago, in Pacitan and Wonogiri, both villages in Central Java. Performances, mostly in small open-sided pavilions or auditoriums, take place according to the following pattern:

The dalang gives a sign, the small gamelan orchestra with drummer and a few knobbed gongs and a musician with a rebab (a violin-like instrument held vertically) begins to play, and the dalang unrolls the first scroll of the story. Then, speaking and singing, he narrates the episode in more detail. In this manner, in the course of the evening he unrolls several scrolls one at a time. Each scene in the scrolls represents a story or part of a story. The content of the story typically stems from the Panji romances which are semi-historical legends set in the 12th–13th century East Javanese kingdoms of Jenggala, Daha and Kediri, and also in Bali.[29]

- Some examples of wayang beber scenes

Radèn Gunung Sari on horse says goodbye to his advisers Tratag and Gimeng before travelling to princess Kumuda Ningrat, 18th century

Radèn Gunung Sari on horse says goodbye to his advisers Tratag and Gimeng before travelling to princess Kumuda Ningrat, 18th century Princess Sekar Taji and Panji meet in Paluhamba market, 17th century

Princess Sekar Taji and Panji meet in Paluhamba market, 17th century Princess Sekar Taji in palace garden approached by Klana, 17th century

Princess Sekar Taji in palace garden approached by Klana, 17th century Competition between Panji Sepuh (left) and Jaya Puspita (right), 18th century

Competition between Panji Sepuh (left) and Jaya Puspita (right), 18th century

Wayang wong

Wayang wong, also known as wayang orang (literally 'human wayang'), is a type of Javanese theatrical performance wherein human characters imitate the movements of a puppet show. The show also integrates dance by the human characters into the dramatic performance. It typically shows episodes of the Ramayana or the Mahabharata.[30]

- Some examples of wayang wong scenes

King Duryodana in a wayang wong performance in Taman Budaya Rahmat Saleh, Semarang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia

King Duryodana in a wayang wong performance in Taman Budaya Rahmat Saleh, Semarang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia Giants in a wayang wong performance

Giants in a wayang wong performance Punokawan in a wayang wong performance

Punokawan in a wayang wong performance

Opening of wayang wong performance, usually showing traditional Javanese dance

Opening of wayang wong performance, usually showing traditional Javanese dance

Wayang topeng

Wayang topeng or wayang gedog theatrical performances take themes from the Panji cycle of stories from the kingdom of Janggala. The players wear masks known as wayang topeng or wayang gedog. The word gedog comes from kedok which, like topeng, means 'mask'.

Wayang gedog centers on a love story about Princess Candra Kirana of Kediri and Raden Panji Asmarabangun, the legendary crown prince of Janggala. Candra Kirana was the incarnation of Dewi Ratih (the Hindu goddess of love) and Panji was an incarnation of Kamajaya (the Hindu god of love). Kirana's story has been given the title Smaradahana ("The fire of love"). At the end of the complicated story they finally marry and bring forth a son named Raja Putra. Originally, wayang wong was performed only as an aristocratic entertainment in the palaces of Yogyakarta and Surakarta. In the course of time, it spread to become a popular and folk form as well.

Stories

Wayang characters are derived from several groups of stories and settings. The most popular and the most ancient is wayang purwa, whose story and characters were derived from the Indian Hindu epics the Ramayana and Mahabharata, set in the ancient kingdoms of Hastinapura, Ayodhya, and Alengkapura (Lanka). Another group of characters is derived from the Panji cycle, natively developed in Java during the Kediri Kingdom; these stories are set in the twin Javanese kingdoms of Janggala and Panjalu (Kediri).

Wayang purwa

Wayang purwa (Javanese for 'ancient' or 'original wayang') refer to wayang that are based on the Hindu epics the Ramayana and Mahabharata. They are usually performed as wayang kulit, wayang golek, and wayang wong dance dramas.[31]

In Central Java, popular wayang kulit characters include the following (Notopertomo & Jatirahayu 2001):[32]

|

|

- Wayang purwa figures from Balinese wayang kulit

Wayang kulit (shadow puppet) Kendran, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1900

Wayang kulit (shadow puppet) Kendran, Tropenmuseum collection, Indonesia, before 1900

Wayang panji

Derived from the Panji cycles, natively developed in Java during the Kediri Kingdom, the story set in the twin Javanese kingdoms of Janggala and Panjalu (Kediri). Its form of expressions are usually performed as wayang gedog (masked wayang) and wayang wong dance dramas of Java and Bali.

- Raden Panji, alias Panji Asmoro Bangun, alias Panji Kuda Wanengpati, alias Inu Kertapati

- Galuh Chandra Kirana, alias Sekartaji

- Panji Semirang, alias Kuda Narawangsa, the male disguise of Princess Kirana

- Anggraeni

Wayang Menak

Menak is a cycle of wayang puppet plays that feature the heroic exploits of Wong Agung Jayengrana, who is based on the 12th-century Muslim literary hero Amir Hamzah. Menak stories have been performed in the islands of Java and Lombok in the Indonesian archipelago for several hundred years. They are predominantly performed in Java as golek, or wooden rod-puppets, but also can be found on Lombok as the shadow puppet tradition, wayang sasak.[33] The wayang golek menak tradition most likely originated along the north coast of Java under Chinese Muslim influences and spread East and South and is now most commonly found in the South Coastal region of Kabumen and Yogyakarta.[34]

The word menak is a Javanese honorific title that is given to people who are recognized at court for their exemplary character even though they are not nobly born. Jayengrana is just such a character who inspires allegiance and devotion through his selfless modesty and his devotion to a monotheistic faith called the "Religion of Abraham." Jayengrana and his numerous followers do battle with the pagan faiths that threaten their peaceable realm of Koparman. The chief instigator of trouble is Pati Bestak, counselor to King Nuresewan, who goads pagan kings to capture Jayengrana's wife Dewi Munninggar. The pagan Kings eventually fail to capture her and either submit to Jayengrana and renounce their pagan faith or die swiftly in combat.

The literary figure of Amir Hamzah is loosely based on the historic person of Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib who was the paternal uncle of Muhammad. Hamzah was a fierce warrior who fought alongside Muhammad and died in the battle of Uhud in 624 CE. the literary tradition traveled from Persia to India and from then on to Southeast Asia where the court poet Yasadipura I (1729-1802) set down the epic in the Javanese language in the Serat Menak.[35]

[36] The wooden wayang menak is similar in shape to wayang golek; it is most prevalent on the northern coast of Central Java, especially the Kudus area.

- Wong Agung Jayengrana/Amir Ambyah/Amir Hamzah

- Prabu Nursewan

- Umar Maya

- Umar Madi

- Dewi Retna Muninggar

- Menak figures from Javanese wayang golek

Wayang Golek menak, King Maktal (Albania), a collection at Tropenmuseum, the Netherlands, before 2003

Wayang Golek menak, King Maktal (Albania), a collection at Tropenmuseum, the Netherlands, before 2003

Wayang Kancil

Wayang kancil is a type of shadow puppet with the main character of kancil and other animal stories taken from Hitopadeça and Tantri Kamandaka. Wayang kancil was created by Sunan Giri at the end of the 15th century and is used as a medium for preaching Islam in Gresik.[37] The story of kancil is very popular with the children, has a humorous element, and can be used as a medium of education because the message conveyed through the wayang kancil media is very good for children. Wayang kancil is not different from wayang kulit; wayang kancil is also made from buffalo skin. Even the playing is not much different, accompanied by a gamelan. The language used by the puppeteer depends on the location of the performance and the type of audience. If the audience is a child, generally the puppeteer uses Javanese Ngoko in its entirety, but sometimes Krama Madya and Krama Inggil are inserted in human scenes. The puppets are carved, painted, drawn realistically, and adapted to the puppet performance. The colors in the detail of the wayang kancil sunggingan are very interesting and varied. Figures depicted in the form of prey animals such as tigers, elephants, buffaloes, cows, reptiles, and fowl such as crocodiles, lizards, snakes, various types of birds, and other animals related to the kancil tale. There are also human figures, including Pak Tani and Bu Tani, but there are not many human figures narrated. The total number of puppets is only about 100 pieces per set.

- Kancil figures in wayang kulit

Kancil

Kancil Srigala

Srigala Macan

Macan Baya

Baya Keong

Keong Nenek Petani

Nenek Petani

Other stories

The historically popular wayang kulit typically is based on the Hindu epics the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.[38] In the 1960s, the Christian missionary effort adopted the art form to create wayang wahyu. The Javanese Jesuit Brother Timotheus L. Wignyosubroto used the show to communicate to the Javanese and other Indonesians the teachings of the Bible and of the Catholic Church in a manner accessible to the audience.[38] Similarly, wayang sadat has deployed wayang for the religious teachings of Islam, while wayang pancasila has used it as a medium for national politics.[38]

There have also been attempts to retell modern fiction with the art of wayang, most famously Star Wars as done by Malaysians Tintuoy Chuo and Dalang Pak Dain.[39]

Cultural context

Its initial function, wayang is a ritual intended for ancestral spirits of the hyang belief. Furthermore, wayang undergoes a shift in role, namely as a medium for social communication. The plays that are performed in the wayang, usually hold several values, such as education, culture, and teachings of philosophy. Wayang functions as an effective medium in conveying messages, information, and lessons. Wayang was used as an effective medium in spreading religions ranging from Hinduism to Islam. Because of the flexibility of wayang puppets, they still exist today and are used for various purposes. Wayang functions can be grouped into three, namely:

Tatanan (norms and values)

Wayang is a performance medium that can contain all aspects of human life. Human thoughts, whether related to ideology, politics, economy, social, culture, law, defense, and security, can be contained in wayang. In the wayang puppets contain order, namely a norm or convention that contains ethics (moral philosophy). These norms or conventions are agreed upon and used as guidelines for the mastermind artists. In the puppet show, there are rules of the game along with the procedures for puppetry and how to play the puppet, from generation to generation and tradition, over time it becomes something that is agreed upon as a guideline (convention).

Wayang is an educational medium that focuses on moral and character education. Character education is something that is urgent and fundamental; character education can form a person who has good behavior.[40]

Tuntunan (guidelines)

Wayang is a communicative medium in society. Wayang is used as a means of understanding a tradition, an approach to society, lighting, and disseminating values. Wayang as a medium for character education lies not only in the elements of the story, the stage, the instruments, and the art of puppetry, but also the embodiment of values in each wayang character. The embodiment of wayang characters can describe a person's character. From the puppet one can learn about leadership, courage, determination, honesty, and sincerity. Apart from that, the puppets can reflect the nature of anger, namely greed, jealousy, envy, cruelty, and ambition.[40]

Tontonan (entertainment)

Wayang puppet performances are a form of entertainment (tontonan) for the community. Wayang performances in the form of theatre performances are still very popular especially in the islands of Java and Bali. Puppet shows are still the favorite of the community and are often included in TV, radio, YouTube, and other social media. Wayang performances present a variety of arts such as drama, music, dance, literary arts, and fine arts. Dialogue between characters, narrative expressions (janturan, pocapan, carita), suluk, kombangan, dhodhogan, and kepyakan are important elements in wayang performances.[40]

Artist

Dalang

The dalang, sometimes referred to as dhalang or kawi dalang, is the puppeteer behind the performance.[2][5][41] It is he who sits behind the screen, sings and narrates the dialogues of different characters of the story.[42] With a traditional orchestra in the background to provide a resonant melody and its conventional rhythm, the dalang modulates his voice to create suspense, thus heightening the drama. Invariably, the play climaxes with the triumph of good over evil. The dalang is highly respected in Indonesian culture for his knowledge, art and as a spiritual person capable of bringing to life the spiritual stories in the religious epics.[2][5][42]

The figures of the wayang are also present in the paintings of that time, for example, the roof murals of the courtroom in Klungkung, Bali. They are still present in traditional Balinese painting today. The figures are painted, flat (5 to at most 15 mm — about half an inch — thick) woodcarvings with movable arms. The head is solidly attached to the body. Wayang klitik can be used to perform puppet plays either during the day or at night. This type of wayang is relatively rare.

Wayang today is both the most ancient and the most popular form of puppet theatre in the world. Hundreds of people will stay up all night long to watch the superstar performers, dalang, who command extravagant fees and are international celebrities. Some of the most famous dalang in recent history are Ki Nartosabdho, Ki Anom Suroto, Ki Asep Sunandar Sunarya, Ki Sugino, and Ki Manteb Sudarsono.

Sindhen

PasindhènPesindhén or sindhén (from Javanese) is the term for a woman who sings to accompany a gamelan orchestra, generally as the sole singer. A good singer must have extensive communication skills and good vocal skills as well as the ability to sing many songs. The title Sinden comes from the word Pasindhian which means 'rich in songs' or 'who sing the song'. Pesindhen can be interpreted as someone singing a song. In addition, sinden is also commonly referred to as waranggana which is taken from a combination of the words wara and anggana. The word wara itself means 'someone who is female' and anggana which means 'itself'; in ancient times, the waranggana was the only woman in the wayang or klenengan performance.

Wiyaga

Wiyaga is a term in the musical arts which means a group of people who have special skills playing the gamelan, especially in accompanying traditional ceremonies and performing arts. Wiyaga is also called niyaga or nayaga which means 'gamelan musician'.

Wayang Museum

The Wayang Museum is located in the tourist area of the Kota Tua Jakarta (old city) in Jalan Pintu Besar Utara No.27, Jakarta 11110, Indonesia. The Wayang Museum is adjacent to the Jakarta Historical Museum.[43]

This museum has various types of Indonesian wayang collections such as wayang kulit, wayang golek, wayang klithik, wayang suket, wayang beber, and another Indonesian wayang. There is also a collection of masks (topeng), gamelan, and wayang paintings. The collections are not only from Indonesia, but there are many collections of puppets from various countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Suriname, China, Vietnam, France, India, Turkey, and many other countries.

Gallery

- Wayang Puppet Theater

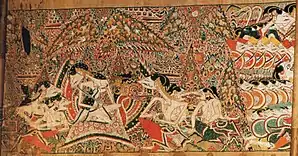

Wayang glass painting depiction of Bharatayudha battle.

Wayang glass painting depiction of Bharatayudha battle. A wayang kulit set and a gamelan ensemble collection, Indonesia section at the Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

A wayang kulit set and a gamelan ensemble collection, Indonesia section at the Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, United States.

_from_central_Java%252C_a_scene_from_'Irawan's_Wedding'.jpg.webp) Wayang (shadow puppets) from central Java, a scene from Irawan's Wedding, mid-20th century, University of Hawaii Dept. of Theater and Dance.

Wayang (shadow puppets) from central Java, a scene from Irawan's Wedding, mid-20th century, University of Hawaii Dept. of Theater and Dance. Wayang beber depiction of a battle.

Wayang beber depiction of a battle..jpg.webp) Wayang kulit and wayang golek dalang (puppeteer), Ki Entus Susmono.

Wayang kulit and wayang golek dalang (puppeteer), Ki Entus Susmono. Wayang golek performance in Yogyakarta.

Wayang golek performance in Yogyakarta. Wayang kulit (leather shadow puppet) performance.

Wayang kulit (leather shadow puppet) performance.%252C_Arjuna_and_Sumbadra_from_Java.JPG.webp) Kayon (Gunungan).

Kayon (Gunungan). Wayang makassar

Wayang makassar

See also

References

- ↑ ""Wayang puppet theatre", Inscribed in 2008 (3.COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (originally proclaimed in 2003)". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Wayang: Indonesian Theatre". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2012.

- 1 2 "History and Etymology for Wayang". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ Siyuan Liu (2016). Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. Routledge. pp. 72–81. ISBN 978-1-317-27886-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Don Rubin; Chua Soo Pong; Ravi Chaturvedi; et al. (2001). The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Asia/Pacific. Taylor & Francis. pp. 184–186. ISBN 978-0-415-26087-9.

- 1 2 Yves Bonnefoy (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- ↑ ""Pertunjukan Wayang Kulit sebagai Atraksi Budaya Baik atau Buruk?"". www.kompasiana.com. 15 December 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ ""Dalang Ruwat, Profesi Tak Sembarangan Ki Manteb Soedharsono"". www.cnnindonesia.com. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ ""Sedekah Bumi dan Wayang Kulit, Cara Bersyukur Petani Atas Panennya"". www.jawapos.com. 10 October 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ ""Wayang Seni Ritual, Dulu Dimainkan Oleh Saman"". www.balihbalihan.com. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ ""Wayang: Aset Budaya Nasional Sebagai Refleksi Kehidupan dengan Kandungan Nilai-nilai Falsafah Timur"". Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture (Kemdikbud). Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ ""Wayang puppet theatre", Inscribed in 2008 (3.COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (originally proclaimed in 2003)". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ↑ Mair, Victor H. Painting and Performance: Picture Recitation and Its Indian Genesis. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988. p. 58.

- ↑ James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 143–145, 352–353. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

- ↑ ""Wayang puppet theatre", Inscribed in 2008 (3.COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (originally proclaimed in 2003)". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 42–44, 65, 92–94, 278. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

- ↑ Miyao, J. (1977). "P. L. Amin Sweeney and Akira Goto (ed.) An International Seminar on the Shadow Plays of Asia". Southeast Asia: History and Culture. Japan Society for Southeast Asian Studies. 1977 (7): 142–146. doi:10.5512/sea.1977.142.

- ↑ Kathy Foley (2016). Siyuan Liu (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. Routledge. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1-317-27886-3.

- ↑ Kathy Foley (2016). Siyuan Liu (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. Routledge. pp. 182–184. ISBN 978-1-317-27886-3.

- ↑ Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1987). History of Indian Theatre, Volume 1. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 75. ISBN 9788170172215.

- ↑ "Keragaman Wayang Indonesia". indonesia.go.id. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ Drs. R. Soekmono (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed. 5th reprint edition in 1988. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 56.

- ↑ "Cerita Panji, Pusaka Budaya Nusantara yang tidak Habis Digali". www.mediaindonesia.com. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ Sumarsam (15 December 1995). Gamelan: Cultural Interaction and Musical Development in Central Java. University of Chicago Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-226-78011-5. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ↑ Eckersley. M. (ed.) 2009. Drama from the Rim: Asian Pacific Drama Book. Drama Victoria. Melbourne. 2009. (p. 15)

- ↑ Simon Sudarman, 'Sagio: Striving to preserve wayang', The Jakarta Post, 11 September 2012.

- ↑ Ganug Nugroho Adil, "Joko Sri Yono: Preserving 'wayang beber'", The Jakarta Post, 27 March 2012.

- ↑ Ganug Nugroho Adil, 'The metamorphosis of "Wayang Beber"', The Jakarta Post, 19 April 2013.

- ↑ Ganug Nugroho Adil, "Sinhanto: A wayang master craftsman", The Jakarta Post, 22 June 2012.

- ↑ James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 46–54, 143–144, 150–152. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

- ↑ Inna Solomonik. "Wayang Purwa Puppets: The Language of the Silhouette", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 136 (1980), no: 4, Leiden, pp. 482–497.

- ↑ Notopertomo, Margono; Warih Jatirahayu. 2001. 51 Karakter Tokoh Wayang Populer. Klaten, Indonesia: Hafamina. ISBN 979-26-7496-9

- ↑ Petersen, Robert S. "The Island in the Middle: The Domains of Wayang Golek Menak, The Rod Puppetry of Central Java. In Theatre Survey 34.2.

- ↑ Sindhu Jotaryono. The Traitor Jobin: A Wayang Golek Performance from Central Java. Translated by Daniel Mc Guire and Lukman Aris with an introduction by Robert S. Petersen. Ed. Joan Suyenaga. Jakarta, Lontar Foundation, 1999.

- ↑ Pigeaud, Th. G. "The Romance of Amir Hamzah in Java." In Binkisan Budi: Een Bundel Opstellen Voor P. S. Van Ronkel: A. W. Sijthoff's Uitgeversmaatschappij N.V., Leiden, 1950.

- ↑ "Amir Hamzah, uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, spreader of Islam, and hero of the Serat Menak". Asian Art Education.

- ↑ ""Wayang Kancil, Seni Pertunjukan"". jakarta-tourism. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 Poplawska, Marzanna (2004). "Wayang Wahyu as an Example of Christian Forms of Shadow Theatre". Asian Theatre Journal. Johns Hopkins University Press. 21 (2): 194–202. doi:10.1353/atj.2004.0024. S2CID 144932653.

- ↑ Sharmilla Ganesan (12 September 2017). "Everything old is new again". The Star. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Pengertian Wayang, Fungsi, Kandungan dan Jenis-Jenis Wayang Lengkap". pelajaran.co.id. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ Sedana, I Nyoman; Foley, Kathy (1993). "The Education of a Balinese Dalang". Asian Theatre Journal. University of Hawaii Press. 10 (1): 81–100. doi:10.2307/1124218. JSTOR 1124218.

- 1 2 Siyuan Liu (2016). Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. Routledge. pp. 166, 175 note 2, 76–78. ISBN 978-1-317-27886-3.

- ↑ ""Museum Wayang Jakarta"". Museum Jakarta. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Signell, Karl. Shadow Music of Java. 1996 Rounder Records CD #5060, Cambridge MA.

- This article was initially translated from the German-language Wikipedia article.

- Poplawska, Marzanna. Asian Theatre Journal. Fall 2004, Vol. 21, p. 194–202.

Further reading

- Alton L. Becker (1979). "Text-Building, Epistemology, and Aesthetics in the Javanese Shadow Theatre". In Aram Yengoyan and Alton L. Becker (ed.). The Imagination of Reality: Essays in Southeast Asian Coherence Systems. Norwood, NJ: ABLEX.

- Brandon, James (1970). On Thrones of Gold — Three Javanese Shadow Plays. Harvard.

- Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof (1994). Dictionary of Traditional South-East Asian Theatre. Oxford University Press.

- Clara van Groenendael, Victoria (1985). The Dalang Behind the Wayang. Dordrecht, Foris.

- Keeler, Ward (1987). Javanese Shadow Plays, Javanese Selves. Princeton University Press.

- Keeler, Ward (1992). Javanese Shadow Puppets. OUP.

- Long, Roger (1982). Javanese shadow theatre: Movement and characterization in Ngayogyakarta wayang kulit. Umi Research Press.

- Mellema, R.L. (1988). Wayang Puppets: Carving, Colouring, Symbolism. Amsterdam, Royal Tropical Institute, Bulletin 315.

- Mudjanattistomo (1976). Pedhalangan Ngayogyakarta. Yogyakarta (in Javanese).

- Signell, Karl (1996). Shadow Music of Java. CD booklet. Rounder Records CD 5060.

- Soedarsono (1984). Wayang Wong. Yogyakarta, Gadjah Mada University Press.

External links

- Historical Development of Puppetry: Scenic Shades (includes information about wayang beber, kulit, klitik and golek)

- Seleh Notes article on identifying Central Javanese wayang kulit

- Wayang Orang (wayang wong) traditional dance, from Indonesia Tourism

- Wayang Klitik: a permanent exhibit of Puppetry Arts Museum

- Wayang Golek Photo Gallery, includes description, history and photographs of individual puppets by Walter O. Koenig

- Wayang Kulit: The Art form of the Balinese Shadow Play by Lisa Gold

- Wayang Puppet Theatre on the Indonesian site of UNESCO

- The Wayang Golek Wooden Stick Puppets of Java, Indonesia (commercial site)

- An overview of the Shadow Puppets tradition (with many pictures) in a site to Discover Indonesia

- Wayang Kulit exhibition at the Museum of International Folk Art

- Wayang Kulit Collection of Shadow Puppets, Simon Fraser University Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology digitized on Multicultural Canada website

- Contemporary Wayang Archive, by the National University of Singapore

- Wayang Kontemporer, an interactive PhD dissertation on Contemporary Wayang Archive

_2.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)