_-_Wasserturm.JPG.webp)

Water supply in Vienna is ensured by two high-source pipelines (also known as high-source water pipelines) as well as various groundwater sources that are integrated into the pipeline system in exceptional cases. In total, up to 589,000 m³ of drinking water can thus be piped into the Austrian capital every day.

The average daily consumption is 367,917 m³ of drinking water, which corresponds to about 221 liters per inhabitant (as of 2010). The highest daily consumption in 2010 was 506,980 m³, the lowest 298,850 m³. The pipe network in the city has a length of about 3,023 km (2010) and supplies about 100,000 houses in Vienna. The operator of the entire water supply system is the Magistrate Department 31 (Wiener Wasserwerke) of the Municipality of Vienna, which is responsible for operation and maintenance. Used water is discharged through the Vienna sewerage system.

History

As early as Roman times, an approximately 20 to 30 km long water pipeline supplied the Roman military camp of Vindobona. It received its water from the streams on the eastern edge of the Vienna Woods. The exact source area is unknown. The last place of discovery is in the Liesing valley near Rodaun, which points to a use of waters of the Liesing catchment area. Although there are references in the literature to an origin of the water from the area of today's Perchtoldsdorf and Gumpoldskirchen on the thermal line, there is no concrete evidence or archaeological sites for this. Regarding the transport capacity of this pipeline, it is published that it could deliver four to eight million liters of water per day. This is considered sufficient to supply a settlement of about 20,000 people including animals according to the state of the art at that time, especially since there was also another pipeline from the area of Hernals (and probably also domestic wells).[1] After the end of Roman rule, the underground pipeline system fell into disrepair and from the Middle Ages until the beginning of the 16th century, water needs were again met from domestic wells. Due to the clayey subsoil and the hygienic conditions of the time, the quality of the well water continuously deteriorated.

It was not until after the great fire in 1525 that the construction of a water distribution system was again considered, primarily to increase the fire-fighting water capacity. In 1562, the House of Habsburg was finally the first to receive its own water supply through the Siebenbrunn court water pipeline, which was built by order of King Ferdinand I. The water was collected in seven wells in Oberreinprechtsdorf (district part of Margareten) and piped in cast-iron pipes to a reservoir under the Augustinerbastei in Vienna, from where it was in turn forwarded to the Hofburg.

From 1565, the Hernalser Wasserleitung (Hernals water pipeline) finally also supplied fresh water for the population. Of the original 1,500 m³ per day, only 45 m³ later remained. The water was now sold from public wells by so-called watermen and waterwomen. Emperor Charles VI, on the other hand, had the water from Kaiserbrunn brought to him in tubs by water riders. From the spring, which the emperor discovered during a hunt, these transports took two and a half days each.

In the 17th century, the fountain at Neuer Markt, which was fed by a spring line, supplied the first parts of the city with fresh water by means of several smaller water pipes. This remained the only water supply system within Vienna until well into the 19th century. So-called waterers – they sold water from tanks on their horse-drawn carts, with which they drove through the city – and house wells continued to supply the majority of the population with water. In 1804, the then suburbs were also supplied with water for the first time thanks to the Albertine water pipeline from Hütteldorf, which was built under Albert of Saxe-Teschen. As pollution increased with the growth of the city, a cholera epidemic struck Vienna for the first time in 1830, killing around 2,000 people by December 1831.

Finally, between 1835 and 1841, Vienna's first area-wide water pipeline system was built: The Kaiser-Ferdinands-Wasserleitung, which brought 20,000 m³ of filtered Danube water into the city every day. The growth of the city soon overtaxed this system – only about four to five liters per day were possible for each inhabitant. Since the water was taken from the nearby Danube Canal, the water was not much purer than that from the domestic wells. Many cases of typhoid and cholera forced action.

In 1861, when seven times the amount of what the Emperor Ferdinand's water pipeline supplied was already needed, there was a public tender in the Wiener Zeitung for a new water supply system. The winning bid was the project of Eduard Suess, a Viennese geologist and municipal councillor, and his associate Carl Junker, which included a 120 km long long pipeline, water reservoirs and a distribution system. The Vienna Council approved the project on 12 July 1864.

Construction work began in 1870. Only three years later, the line running from the Rax-Schneeberg region of Lower Austria along the Thermenlinie to Vienna, the First Vienna Mountain Spring Pipeline was completed and opened by Emperor Franz Joseph I on the occasion of the Vienna World's Fair on 24 October 1873, as Europe's largest water pipeline. To commemorate this construction, the high-jet fountain was erected in Vienna on Schwarzenbergplatz. At the same time, the elevated tanks on Rosenhügel, Schmelz, Wienerberg and Laaerberg were built.

As early as 1888, 90% of the residential buildings in Vienna at that time were connected to the network, which meant that the majority of the approximately 900,000 inhabitants could be supplied with clean drinking water. Every floor had a faucet with a vitreous enamel – the bassena, which is still present in many houses of that time.

On 6 November 1896 the first pumping station in Vienna, the Breitensee pumping station at Hütteldorfer Strasse 142, was put into operation.

After a long legal dispute, the Wienerwaldsee was constructed in Untertullnerbach between 1895 and 1898 by the Belgian Compagnie des Eaux de Vienne, Societé anonyme. The water treated in the Wientalwasserwerk was sold as utility water to the city of Vienna, which resold it to various customers. In 1958, the city of Vienna acquired the waterworks and, after appropriate modifications, used it as a drinking water plant until 2004. Today, the Wiental reservoir serves as a retention basin – in other words, as a rainwater retention basin.

Due to the rapid development of the city, the water supplied by the first high-spring pipeline was soon no longer sufficient. Therefore, already at the beginning of the 20th century, under Mayor Karl Lueger, the II. Vienna high spring line was built. This is fed by springs in the Hochschwab Mountains and was also opened by Emperor Franz Joseph in 1910.

The deep wells in the Lobau have existed since 1966 and are used in special cases or in the event of exceptionally high water consumption. The water is bank filtrate from the Danube, which is somewhat harder than spring water due to the long flow time underground.

In the 1970s, groundwater lakes were developed in the eastern Vienna Basin, the Mitterndorfer Senke. However, because of groundwater lake contamination, including from the former Fischer landfill, this water has to be treated. The many tests and procedures took until 2004, so they have only been supplying water since 2006.

As of 2023, about 1,300 municipal drinking fountains are served in Vienna, including 100 with spray installations, as well as 55 monumental fountains.[2]

General

Capacity

The individual plants can deliver the following maximum quantities per day:

- I. High source pipeline: 220.000 m³

- II. High source pipeline: 217.000 m³

- Lobau groundwater plant: 80.000 m³

- Waterworks Moosbrunn: 62.000 m³

- Various smaller water dispensers: 10.000 m³

This results in a total of 589,000 m³. The average daily consumption of about 375,000 m³ is served by the two high-source pipes (I. 173,000 m³, II. 202,000 m³). In the event of exceptionally high water consumption and in special cases, such as maintenance work or so-called sweeping, recourse is made to the deep wells in the Lobau, the Moosbrunn waterworks or other even smaller wells.

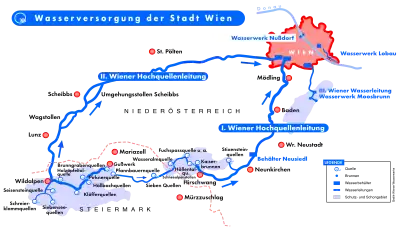

General Map

First high source line

The sources of the largely brickwork Kaiser Franz Josefs-Wasserleitung, as the First high source line was originally called, are located near Kaiserbrunn in the Schwarza Valley between the high plateau of the Rax, which rises to 2,007 meters, and the Schneeberg, the highest mountain in Lower Austria at 2,076 meters. Over the years, other springs, such as those in Gußwerk or at the foot of the Schneealpe, were fed into the First High source line. The course leads from Kaiserbrunn via Hirschwang through the Höllental by means of a 3 km long tunnel, through a walled canal further on via Payerbach, Neunkirchen, Bad Vöslau, Baden, Mödling to the water reservoirs such as the elevated tank at Rosenhügel in Hietzing, from where it is then further distributed.

The water flows for 16 hours until it arrives in Vienna. The difference in altitude is 276 m. It warms up by 1.5 – 2 °C in the process. Since the water flows freely downhill the entire way, no pumping stations are necessary. In the years 1953–1959 the water reservoir Neusiedl am Steinfeld was built with a capacity of 600,000 m³, which is one of the largest water reservoirs in Europe. The Schneealpen tunnel, which was built between 1965 and 1968, also allows spring water to be fed in from Styria.

The pipe network for the first high spring pipeline was built by the company Elsner & Stumpf, which equipped many buildings with water pipes.

Along the First high source line, the water pipeline trail was established, which leads from Kaiserbrunn to Gloggnitz and Bad Vöslau to Mödling.

The spring areas on Rax and Schneeberg largely belong to the municipality of Vienna, are managed by the forestry administration of the city of Vienna and are today almost entirely designated as water protection, spring protection and landscape protection areas.

Second high source line

The Second High Springs Pipeline is fed by springs in the Hochschwab region. It was opened in 1910, also by Emperor Franz Joseph. It, too, has sufficient gradient to Vienna so that no pumps are needed. As with the first high-spring pipeline, there are already large differences in altitude in the spring area. This pressure is relieved in turbines as a pressure brake, which supply the surrounding area from Wildalpen to Mariazell with electricity. One of the best known of these power plants is the Gaming water pipeline power plant. The 200 km long pipeline, which largely consists of stone galleries, runs over 100 aqueducts and 19 culverts, which were built from cast iron pipes, as they have to withstand up to 9 bar in places. The water needs about 36 hours for the distance from the source area to Vienna. The pressure of the inflow to the Lainz elevated tank is also so high that a turbine was also installed there, which is now to be reactivated for energy generation. In the area of larger rivers, drain sluices have been installed, which allow the pipeline to be drained for maintenance and cleaning work, the so-called sweep.

The largest of the springs is the Kläfferquelle at the foot of the Hochschwab in the Styrian Salzatal, which has a discharge of 10,000 l/s when the snow melts (that is about 860,000 m³ or 860 million liters per day), making it one of the largest sources of drinking water in Europe. However, the pipeline has a capacity of only 210,000 m³ per day with an average pipeline cross-section of 1.16 to 1.92 m wide and 1.58 to 2.08 m high.

The course of the pipeline leads from Wildalpen, Lunz am See, Scheibbs, Wilhelmsburg and Neulengbach via Preßbaum to Vienna.

The largest part of the spring area belongs to the municipality of Vienna, which had bought it from Admont Abbey.

Third water pipe

The III. Vienna water pipeline connects the Moosbrunn waterworks in the Mitterndorf Valley about 30 km south of Vienna. It supplies about 64,000 cubic meters per day, which is a good quarter of the supply of each of the two high-source pipelines. The plant has been in operation since 2006.[3]

Elevated tank

About thirty elevated tanks supply drinking water to the city, which is divided into seven pressure zones.[4] 95% of the households are supplied due to gravitational energy – i.e. without a pump. Only a few pressure zones ("yellow") have to be supplied with pumps, for example the residential park Alterlaa or the Millennium Tower, which have their own pumps.

Striking elevated tanks are the meanwhile decommissioned water tower Favoriten at Wienerberg or also the water tank Bisamberg, whose facade was designed by the sculptor Gottfried Kumpf. Due to the many reservoirs, the daily peaks can be covered.

Water quality

Due to the location of the springs in the pure karst area, the flow rate through the soil is usually very high. Since the water flows through the limestone stock after 8 to 10 hours already again from the source, the purification effect is not very strong. However, the spring area in the foothills of the Alps was declared a water protection area as early as 1965, covering an area of 600 km2. As a result, even today, despite changes in environmental conditions, the water from the two high spring water lines is so clean that it does not need to be treated.

Wiener Wasserwerke works closely with the city of Vienna's Forestry Department to carry out targeted reforestation to increase the formation of humus, which is capable of storing and purifying water. In addition, the city of Vienna has also participated in a professional water disposal system for the mountain huts located in the area. Due to the short stay of the water in the ground, it is rather soft with 7–9 German degrees of hardness (dH). Water from the Lobau waterworks has a total hardness of about 18 dH. The hardness of tap water varies in all districts between 6 and 11 (in some up to 14 dH).

Water price

In 2019, the water price was 1.92 euros per cubic meter, and the water meter fee was 25 to 309 euros per calendar year, depending on the connection size.[5]

Museums

There are two museums in Kaiserbrunn and in Wildalpen, which deal specifically with the construction and operation of the water pipeline:

- Kaiserbrunn Water Pipeline Museum in Reichenau an der Rax.

- Water Pipeline Museum Wildalpen in the Styrian Salzatal valley

The water tower on the Wienerberg is regularly used for exhibitions that have nothing to do with water. To the west of it is the water playground Wasserturm, where the water festival is held in June.

Additional tasks for the city of Vienna

On the occasion of the granting of the water consents for the two high spring water pipelines, the city of Vienna was also obliged, among other things, to supply drinking water to Naßwald and Matzendorf, but also to maintain roads and bridges in the forest areas. For example, in the province of Lower Austria, the city of Vienna looks after 32 bridges in the Nasswald, Hirschwang and Stixenstein areas, and in the province of Styria, 21 bridges in the Wildalpen area. In 2011, for example, the Rechenbrücke and the Schneiderbrücke were newly built by the city of Vienna.[6]

International Association of Water Service Companies in the Danube River Catchment Area (IAWD)

The International Association of Water Service Companies in the Danube River Catchment Area, founded in 1993, has its headquarters at the Vienna Waterworks in the Grabnergasse office building in Vienna (Mariahilf).

See also

- Assistance Wildalpen Scream Spring

References

- ↑ Ruth Koblizek, Nicole Süssenbek (2020). Die Trinkwasserversorgung der Stadt Wien von ihren Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie eingereicht an der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Wien. Römische Wasserleitung, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Brunnen in Wien. wien.gv.at. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ↑ Wasserwerk Moosbrunn. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ Franz Weyrer. Rohrnetzrehabilitation Strategie 2008 (mit Stadtplan der Druckzonen auf p. 4)

- ↑ Wasserbezugs- und Wasserzählergebühr – Meldung. Stadt Wien. Retrieved 10 May 2020 (see Unterpunkt „Kosten und Zahlung“).

- ↑ Neubau der Rechenbrücke und der Schneider Brücke. Wiener Brückenbau und Grundbau (Magistratsabteilung 29). Retrieved 21 May 2014.

Bibliography

- A. Drennig: Die I. Wiener Hochquellenwasserleitung. Festschrift herausgegeben vom Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Abt. 31 – Wasserwerke, aus Anlass der 100-Jahr-Feier am 24. Oktober 1973. Jugend und Volk, Wien 1973, ISBN 3-7141-6829-X

- A. Drennig: Die II. Wiener Hochquellenwasserleitung. Festschrift herausgegeben vom Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Abt. 31 – Wasserwerke. Compress-Verlag, Wien 1988, ISBN 3-900607-11-7

External links

- Municipal Department 31 – Vienna Waterworks

- History of the Water Supply in Vienna

- Museum HochQuellenWasser Wildalpen

- Vienna's two high-spring water pipelines – what else they bring (Memento of 18 December 2010 in the Internet Archive)

- Interview with Hans Sailer, Director of Wiener Wasserwerke

- Waterworks Vienna

- Wiener Wasser Documentary by Georg Riha, Manfred Christ and Harald Pokieser, ORF 2010, 3sat