| Waste House | |

|---|---|

_(17).JPG.webp) The building from the south-southeast | |

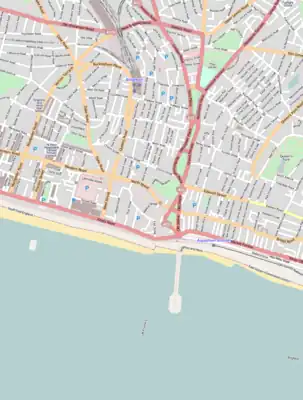

Location in central Brighton | |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Architectural style | Contemporary (Sustainable) |

| Address | University of Brighton Faculty of Arts, 58–67 Grand Parade, Brighton BN2 0JY |

| Town or city | Brighton and Hove |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 50°49′25″N 0°08′05″W / 50.823547°N 0.134809°W |

| Groundbreaking | 26 November 2012 |

| Construction started | May 2013 |

| Completed | April 2014 |

| Opening | 10 June 2014 |

| Cost | £140,000 |

| Owner | University of Brighton |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Duncan Baker-Brown |

| Architecture firm | BBM Sustainable Design |

| Main contractor | Mears Group |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4][5][6][7] | |

Waste House is a building on the University of Brighton campus in the centre of Brighton on the south coast of England. It was built between 2012 and 2014 as a project involving hundreds of students and apprentices and was designed by Duncan Baker-Brown, an architect who also lectures at the university. The materials consist of a wide range of construction industry and household waste—from toothbrushes and old jeans to VHS cassettes and bicycle inner tubes—and it is the first public building in Europe to be built primarily of such products. "From a distance [resembling] an ordinary contemporary town house",[8] Waste House is designed to be low-energy and sustainable, and will be in continuous use as a test-bed for the university's design, architecture and engineering students. The building has won several awards and was shortlisted for the Royal Institute of British Architects' Stephen Lawrence Prize in September 2015.

Background

Waste House has its origins in an earlier project by Duncan Baker-Brown,[9] a senior lecturer at the university and a director of architecture firm BBM Sustainable Design[9] based at Cooksbridge railway station in East Sussex.[10] On Channel 4 television programme Grand Designs, he and designer and television presenter Kevin McCloud assembled a "low-energy ... ecologically friendly" prefabricated house made of organic materials. It was the first such building to be constructed in the United Kingdom.[9][11] Baker-Brown was responsible for the design of this building, which was in turn referred to as "The House that Kevin Built".[7] Originally Baker-Brown planned simply to take down the building and re-erect it at the University.[7] Instead, the temporary building formed the prototype for Waste House, and since 2008 work has been undertaken at the University of Brighton Faculty of Arts to develop the ideas and techniques used on the programme in order to build a permanent house which can be used to test materials, construction theories and new techniques.[12] It is intended to be "a real live research project"[7] as well as a building which the university and other groups can use.[12][13]

Design and construction

Work was planned to begin in 2012 in time for an end-of-year completion date and a public opening in February 2013.[12] These dates were not achieved, but preparation started on 26 November 2012[5] and by May 2013 construction was underway.[4][9] Work finished in April 2014, the building was featured as part of the Brighton Festival the following month,[4] the public were able to view the interior during June 2014, and by August 2014 Waste House was complete.[12] Construction cost £140,000[6] and the total value of the contract was £200,000.[14] Waste House is the first permanent public building in Europe made from waste material.[1][3]

Over 300 students from the University of Brighton, City College Brighton & Hove (CCB) and apprentices from housing provider Mears Group were involved in the project.[1] The construction work was mainly undertaken by CCB students, the Mears apprentices and some volunteers,[4] led by a project manager from Mears Group.[9] Students learning carpentry at CCB designed the timber-framed structure and the "fine timber staircase, finished with a decorative flourish of offcuts".[2] Many of the structural elements were created in the college's own workshops. University of Brighton Faculty of Arts students worked with Baker-Brown on the design, the selection of materials and on interior features such as furniture. Overall, 97.5% of the time taken to build Waste House—2,507 person-days—was provided by students and volunteers,[4] and about 700 people worked on the project.[9] A major aim of the project was to introduce students and apprentices to sustainable building techniques and to allow them to continue testing their ideas by retrofitting new fixtures.[5]

Materials

The purpose of building Waste House was to demonstrate that material considered to be waste, and therefore destined for landfill, could be used to create a viable permanent building. Baker-Brown stated that in the United Kingdom, 20% of construction materials go to waste—so the equivalent of one house worth of unwanted material is generated for every five houses built.[1][2] Between 85%[3] and 90%[1] of the materials used in Waste House are building waste of this type or ordinary household and consumer products which are no longer needed.[12]

_(7).JPG.webp)

Structurally, the building is timber-framed[15] and uses a mixture of reclaimed wood and plywood from various sources around Brighton. It has been constructed on foundations of ground granulated blast-furnace slag.[4][13] The "rather unusual"[15] walls consist of a mixture of waste chalk and clay left over or reclaimed from building sites.[15] These are compressed into rammed earth-style walls using pneumatic equipment—a technique which improves the building's energy conservation, because such walls store solar energy for a long time.[12] On the outside the walls are covered with "a scaly surface of rubbery black shingles"—2,000 carpet tiles from an old office building in Brighton. Their fire-retardant, waterproof underlay faces outwards, providing weatherproof cladding and insulation.[2][4] Their mostly black appearance is varied in places by being laminated with plastic bags in various colours.[7] Between the carpet tiles and the walls themselves, some new material was used: DuPont supplied about 400 square metres (4,300 sq ft) of "breathable membrane", to further weatherproof the building, and "Housewrap" moisture seal.[15] Inside, the walls are laid with reclaimed plasterboard coated with surplus paint from construction sites.[2] The main load-bearing wall is formed of 10 tonnes of compressed chalk spoil from a building site nearby.[4] Throughout the building, the space between the boarding and the exterior clay and chalk blocks has been filled with household rubbish which will act as insulation. Sensors have been installed to monitor how well heat is kept in,[4] which will form part of a PhD project for a University of Brighton student.[12][7] The insulation materials are revealed in various places by "little peephole windows"[2] (transparent panels in the walls):[4] as well as some secondhand conventional (polyurethane) insulation material,[2] there are floppy disks, 4,000 VHS cassettes, 4,000 DVD and video cases, two tonnes of denim offcuts from pairs of jeans and denim jackets, cycle inner tubes to insulate windows, and 20,000 toothbrushes.[2][4] The cassettes and other media came from the stock of rental shops which were closing down; an aeroplane cleaning company at nearby Gatwick Airport donated most of the toothbrushes, which were provided to First and Business Class passengers and discarded after one use,[12] and some others were provided by Brighton schoolchildren; and the denim came from textile traders[4][2][7] (in particular, one company which turned imported jeans into denim shorts by cutting off the legs).[2]

Many materials were obtained on the Freegle website—a free reuse and recycling service developed from The Freecycle Network.[2] These include the clay tiles on the roof,[2] the kitchen[4] and some of the insulation material.[7] Cat Fletcher, one of the founders of Freegle UK, was part of the Waste House project team[9] and was responsible for obtaining many of the materials, both from Freegle members (numbering 18,000 in the Brighton area) and from other sources.[16][17] Other than the specialist cladding materials supplied by DuPont, the only new products used in the building are the triple-glazed windows and the material used in the wiring and plumbing.[2]

Awards and reception

In September 2015, Waste House was nominated for that year's Stephen Lawrence Prize. This Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) award, named after the aspiring architect who was murdered in 1993, is for projects with a budget of up to £1 million. In its shortlisting for the award, which was judged in mid-October 2015, judges from the RIBA stated that the house "has sufficient scientific integrity to be taken seriously by the construction industry" and the potential to alter political attitudes to recycling.[1] Waste House was one of seven buildings nominated for the prize, which was won by a fishing hut designed by Niall McLaughlin Architects.[18]

Waste House was one of several buildings in Sussex, along with the Chichester Festival Theatre and St Botolph's Church at Botolphs, to win an award at the RIBA South East Regional Awards in April 2015. It was described as "a project with an interesting agenda" and "a collective of experiments in which students learn by application".[16] Duncan Baker-Brown also won an Argus Achievement Award from local newspaper The Argus.[16]

RIBA awarded Waste House a Sustainability Award in 2014.[16] It described "some of the experiments [as] extraordinary", commenting specifically on the toothbrush insulation and the vinyl banner vapour control layers, and noted that "the continually evolving [design] brief" would "continue to question important issues of recycling that affect everyone".[14]

The 2Degrees Network, a worldwide collaborative association of sustainable businesses,[19] awarded the building a Champions Award in 2014. Waste House was described as "an investment in educating the next generation of designers and builders to think and build more sustainably".[17]

In view of its low energy use, Waste House has a building energy rating of A.[3] When work started, Baker-Brown stated the aim of making it one of the United Kingdom's first A*-rated buildings.[5][11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 le Duc, Frank (14 September 2015). "Waste House in Brighton shortlisted for Stephen Lawrence Prize". Brighton & Hove News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Wainwright, Oliver (7 July 2014). "The house that 20,000 toothbrushes built". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Brighton 'Waste House'". University of Brighton Faculty of Arts. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Waste House by BBM is "UK's first permanent building made from rubbish"". Dezeen Ltd. 19 June 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Work starts on the house made from waste". Mears Group plc. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 Hartman, Hattie (28 July 2014). "Brighton Waste House". Architects' Journal. EMAP Publishing Ltd Co. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pero, James (November 2014). ""Waste House" an Example of Sustainable Building". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Waste House, Grand Parade Campus, Brighton University". BBM Sustainable Design. 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Team". University of Brighton Faculty of Arts. 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Contact BBM". BBM Sustainable Design. 2015. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Brighton university recreates designer's rubbish house". BBC News. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "About". University of Brighton Faculty of Arts. August 2014. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- 1 2 Mok, Kimberley (25 June 2014). "Built with 85% junk, Waste House will be university's "living laboratory" (Video)". TreeHugger. MNN Holding Company, LLC. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Brighton Waste House, Brighton". RIBA Journal. Royal Institute of British Architects. 24 April 2015. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "DuPont™ Tyvek® advanced breather membranes help waste products to perform in unexpected ways in a new building experiment". DuPont. 2015. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 James, Ben (24 April 2015). "Waste house given a top design gong". The Argus. Newsquest Media (Southern) Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- 1 2 Baker-Brown, Duncan (5 March 2014). "How can 20,000 old toothbrushes be used to insulate a house? Brighton's Waste House explains all". 2degrees Ltd. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Stephen Lawrence Prize 2015". Royal Institute of British Architects. 2016. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Our Story". 2degrees Ltd. 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

External links

Media related to Waste House, Brighton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Waste House, Brighton at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)