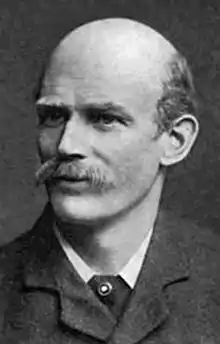

Walter Bache (/ˈbeɪtʃ/; 19 June 1842 – 26 March 1888) was an English pianist and conductor noted for his championing the music of Franz Liszt and other music of the New German School in England. He studied privately with Liszt in Italy from 1863 to 1865, one of the few students allowed to do so, and continued to attend Liszt's master classes in Weimar, Germany regularly until 1885, even after embarking on a solo career. This period of study was unparalleled by any other student of Liszt and led to a particularly close bond between Bache and Liszt. After initial hesitation on the part of English music critics because he was a Liszt pupil, Bache was publicly embraced for his keyboard prowess, even as parts of his repertoire were questioned.

Bache's major accomplishment was the establishment of Liszt's music in England, to which he selflessly devoted himself between 1865 and his death in 1888. This was at the height of the War of the Romantics, when conservative and liberal musical factions openly argued about the future of classical music and the merits of the compositions written in their respective schools. Bache featured several of the orchestral and choral works through an annual series of concerts, which he single-handedly funded, organised and promoted. Likewise, he played an annual series of solo recitals that incorporated Liszt's piano music.

Bache's strategy for presenting these works was one of familiarity. He performed two-piano arrangements of Liszt's orchestral works prior to the debuts of the original versions, and performed some of Liszt's symphonic poems shortly after they had been premiered at the Crystal Palace. He also provided informative, scholarly program notes, written by leading musical analysts and intimates in the Liszt circle. The English musical press, while generally hostile to the music he presented, noted and appreciated Bache's efforts. Liszt remained grateful; without Bache, he acknowledged, his music might not have gained the foothold that it did.

Life

Early years

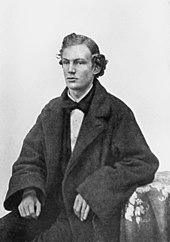

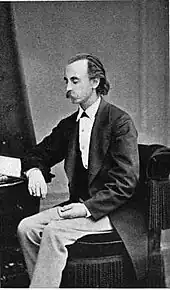

Bache was born in Birmingham, the second-oldest son of well-known Unitarian minister Samuel Bache, who ran a private school in conjunction with his wife, Emily Higginson.[1] His older brother, Francis Edward Bache, was a composer and organist, while his sister, Constance Bache, was a composer, pianist and teacher who would write a joint biography of both brothers under the title Brother Musicians. He received some rudimentary musical education at his father's school, but remained a carefree, undistinguished and funloving child until he followed in Edward's footsteps.[2] Like Edward, he studied with Birmingham City Organist James Stimpson and in August 1858, aged 16, he travelled to Germany to attend the Leipzig Conservatory. His father was supposed to accompany him to the university, but was detained at the bedside of Edward, who was dying of consumption. Undeterred, he made the journey on his own, an early indication of his independence.[1]

In Leipzig, Bache studied piano with Ignaz Moscheles and composition with Carl Reinecke. He also became friends with a fellow student, Arthur Sullivan, who, he wrote, "cannot play well, but ... has written some things which I think show great talent."[3] Another fellow student Bache knew well, though they were not especially close, was Edvard Grieg.[4] While the city was reportedly past the halcyon days it had experienced under Mendelssohn,[5] it proved valuable for exposing Bache to artists such as Pauline Viardot, Giulia Grisi, Joseph Joachim and Henri Vieuxtemps, and to the music of Beethoven, Bellini, Chopin, Moritz Hauptmann and Mendelssohn.[6] He applied himself to his piano studies, but by his own admission wasted much time in Leipzig and lacked direction.[7] In Brother Musicians, Constance quotes "a musician of high standing" who was one of his circle of friends (possibly Sullivan or the pianist Franklin Taylor),[6] who explained, "You see in Leipzig nobody was compelled to work, there being no particular supervision; and there was always plenty to do, in the way of amusement, for the less energetic. As far as my recollection goes Bache was at that time rather given to working by fits and starts, frequently making excellent resolutions, the effect of which did not last many days."[8]

Upon completing his piano studies in December 1861, the 19-year-old Bache travelled to Italy, staying in Milan and Florence with the intent of soaking in Italian culture before returning to England.[9] In Florence he met Jessie Laussot, "who had founded of a flourishing musical society in the city ... and was intimately acquainted with Liszt, Wagner, Hans von Bülow and other leading musicians."[1] While Laussot remained kindly disposed towards Bache, she also quickly summed up his overly easy-going character and decided to help him. She encouraged him to teach harmony as well as piano, then arranged a harmony class that met early in the morning some ways out of town so that he would not oversleep.[10] She eased his way into polite society[6] and also suggested, after hearing him play at several local concerts, that he travel to Rome and seek out Liszt.[1] However, she insisted that he do so without any introduction from her, as she wanted Liszt to judge him solely on his own merits.[11]

Studies with Liszt

Bache arrived in Rome in June 1862. After some initial confusion (Liszt mistook Bache, who was nervous and tongue-tied, for someone wanting to borrow money)[12] Liszt made Bache welcome. Two or three impromptu lessons followed, along with some chamber music appearances, thanks to Liszt's recommendation. Eventually, Liszt suggested that, if Bache were willing to move to Rome the following year, he would take him on as a regular student.[13] Considering this "the greatest possible advantage I could have",[14] Bache wrote to Constance,

I hope I have not exaggerated in talking about Liszt; he won't make me anything wonderful, so that I can come home and set the Thames on fire—not at all, so don't expect it; but—his readings or interpretations are greater and higher than anyone else's; if I can spend some time with him and go through a good deal of music with him, I shall pick up at least a great deal of his ideas;... The two or three lessons I had of him this summer showed me what an immensity I might learn.[15]

After a visit to Birmingham, Bache moved to Rome in 1863 and lived there the next two years. While there he received private lessons from Liszt, one of the few pupils thus privileged; most of Liszt's students attended only his master classes. He also heard Liszt play his own music on many occasions in private homes, including a then-rare performance of the Piano Sonata in B minor. Liszt helped him prepare for several public concerts in Rome and encouraged him to learn some difficult pieces that Bache initially felt unable to play; these pieces included Liszt's transcriptions of Gounod's Faust Waltz and Meyerbeer's "Patineurs" Waltz from his opera Le prophète.[16] These lessons, the kindness that Liszt continually showed, and Bache's exposure to Liszt in general, became a life-defining experience.[17][18] Liszt expected him to work hard and Bache applied himself with a purpose to his keyboard studies.[13] The same "musician of high standing" that Constance quotes about Bache's years in Leipzig also states that "there can be no doubt that it was his friendship with Liszt that he owed that enthusiasm and power of sustained hard work which distinguished him during his career in London, and which was often the astonishment of those who had known him in earlier years."[8]

Bache supported himself as an organist at the English Church, where the chaplain had previously known Bache's brother Edward.[19] As his reputation as a performer grew, he also came into demand as a teacher. These two activities guaranteed financial security.[20] He also became acquainted with several young gifted musicians, including fellow Liszt pupil Giovanni Sgambati and violinist Ettore Pinelli.[20] During this time, Bache began exploring the two-piano repertoire, especially the arrangements of Liszt's symphonic poem Les préludes and Schubert's Wanderer Fantasy, which he performed with Sgambati in concert.[21][22] The two-piano arrangements of Liszt's symphonic poems would become an important feature of Bache's concert series once he returned to England.[21] He was also active in chamber music—the works he performed during this time include Chopin's cello sonata, the David-Pinelli Violin Variations, Mendelssohn's D minor piano trio, a piano trio by Anton Rubinstein and a Schumann violin sonata arranged for viola.[6]

Bache's studies with Liszt did not end when he left Italy. He attended Liszt's master classes in Weimar, Germany regularly until 1885.[21] This period of study was unparalleled by any other student of Liszt and led to a particularly close bond between Bache and Liszt.[23] He also sought out his fellow pupil Hans von Bülow for lessons in 1871; the two spent much time together, which resulted in a lifelong friendship.[24] The fact Bache valued Bülow's advice highly is shown by his warning to Jessie Laussot to "never again attempt to 'mark, learn and inwardly digest' the [Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue] without getting Bülow's edition of it ... it is splendid—quite equivalent to having had a lesson on it from Liszt".[25]

For Bache, Liszt wrote his concert arrangement of the Sarabande and Chaconne from Handel's opera Almira in 1879.[26]

Promoting Liszt's music

Before he moved to Rome, in June 1863, Bache returned to Birmingham to raise funds for the erection of a memorial window to his brother Edward. Among these efforts was a performance of Mendelssohn's oratorio St. Paul, at which his organ playing was noted, and a solo piano recital which featured a few pieces by Liszt.[13] Critics proved unreceptive to Liszt's music and Bache was advised to program less adventurous works if he wanted his career to succeed.[27] Matters had not improved when Bache settled in London in 1865. The War of the Romantics between musically conservative and liberal factions was in full swing and he found himself branded as "dangerous" for having studied with Liszt.[28] This was vividly illustrated when Bache called upon J. W. Davison, then the most powerful music critic in London. Such a call was not unwarranted: Davison had been acquainted with Edward and shared that brother's conservative musical views. Bache related that when he called on Davison and handed in his card, the maid returned and told him, "Please, sir, Mr. Davison says that he is not at home."[28]

Dangerous or not, Bache soon began a lifelong crusade to win popularity for Liszt's works in England. In 1865 he began a series of annual concerts in conjunction with singer Gustave Garcia.[21] They began modestly, in Collard's Rooms, Grosvenor Street. As they increased in popularity, they were relocated to the more spacious Beethoven Rooms in Cavendish Square, then to the Queen's Concert Rooms in Hanover Square, and finally to St James's Hall in Regents Square.[29] At first these concerts were of instrumental and chamber works and piano arrangements. In 1868, they had grown to include choral works, which allowed pieces such as Liszt's Soldatenlied and choruses from Wagner's Tannhäuser and Lohengrin to be programmed.[30] By 1871, the concerts had been changed to an orchestral format.[17][21]

The concerts, which were held in February or March and continued until 1886, became known as the "Walter Bache Annual Concerts."[30][31] They became fixtures on the London music scene, attracting the attention of the press[31] and of eminent musicians.[32] While some of the press coverage he received was positive, overall Bache faced a continual barrage of opposition and scorn from critics and fellow musicians over the music he presented. The notice printed in the Athenaeum after the first concert was typical: "On Tuesday, M. Gustave Garcia, one of the best of rising baritones, and Mr. Walter Bache gave a concert in company. We cannot think Les Préludes, a very difficult duett [sic] by the Abbé Liszt for two pianofortes, worth the labour bestowed on it by a couple of players so skilled as himself and Mr. Dannreuther. It was well received however."[33] Largely through Bache's perseverance, at least some of the public was gradually convinced of the music's worth.[34]

At these concerts, Bache frequently appeared as soloist, accompanist or conductor, but he also engaged other artists in an attempt to show he was not giving the concerts out of self-aggrandizement. Bülow conducted two concerts, Edward Dannreuther led the orchestra in two concerts. August Manns, the conductor of a series of orchestral concerts held at the Crystal Palace and an admirer of Liszt's works, led four concerts.[35] The majority of instrumentalists engaged were also members of the Crystal Palace orchestra to ensure the level of performance was as high as possible.[36] Among guest soloists was the noted violinist August Wilhelmj, who played the Bach Chaconne in D minor at one concert.[31]

For these concerts, Bache programmed five of Liszt's symphonic poems, the Faust and Dante symphonies, the Thirteenth Psalm and the Legend of St. Elisabeth.[34] Works of Berlioz, Schumann and Wagner were also featured, but Liszt's compositions predominated.[37] While the performances of the Faust and Dante symphonies were British premieres, the symphonic poems had previously been introduced at the Crystal Palace; nevertheless, Bache felt that offering repeat performances of the symphonic poems was important in making them familiar to audiences.[36] Les préludes was performed three times at the Bache concerts, Mazeppa, Festklänge and Orpheus each twice and Tasso once.[36] Part of this strategy of familiarity was the inclusion of the two-piano arrangements of the symphonic poems as a way to prepare audiences for the orchestral versions.[32] Bache had begun this practice with his first concert in 1865, when he and Dannreuther presented the two-piano arrangement of Les préludes.[17] Another part of this strategy was supplying learned, well-considered and thoroughly detailed essays for program notes. Sometimes Bache wrote them himself; at other times, he relied on prominent theorists such as Carl Weitman and Frederick Niecks. According to musicologist Alan Walker, they "are filled with insights that were both new and original for their time, and they are lavishly illustrated with music examples—a sure sign that they were aimed at a sophisticated public and were intended to have a potential life after the concert was over."[38] According to Walker, they still are worth study for Liszt scholars as many of the ideas, while transmitted through members of Liszt's inner circle, probably originated with the composer himself.[38] These notes, along with the inclusion of the two-piano arrangements and what musicologist Michael Allis calls "a thoughtful approach to programming ... all contributed to an aggressive marketing of Liszt's new status as a composer".[32]

The concerts were a considerable financial outlay for Bache, who did not have a regular salary until 1881 and had to sustain himself through teaching. By 1873, he wrote, he had to "decide whether I shall sacrifice myself entirely to the production of Liszt's orchestral and choral works (which after all can never be immortal as Bach, Beethoven and Wagner: here I feel that Bülow is right). Or shall I make my own improvement the object of my life, and not spend a third of my income in one evening."[39] Bülow became concerned enough about the situation to waive his fee after one concert he conducted, and to contribute £50 out of his own pocket.[31] Liszt was also concerned, writing, "For years [Bache] has sacrificed money for the performance of my works in London. Several times I advised him against it, but he answered imperturbably, 'That is my business.'"[40] Whenever Bache was asked about finances for the concerts, he would tell whoever was asking that the cost was "a just recompense" and add that even if Liszt had charged him for his lessons at the same rate as the average village piano teacher, he would still be deeply in his debt.[41]

In addition to the orchestral concerts, Bache gave an annual series of solo recitals on Liszt's birthday, 22 October, between 1872 and 1887.[42] In October 1879, Bache gave his first all-Liszt recital.[43] At some of these recitals, the two-piano arrangements of Liszt's orchestral works were given. The two-piano version of Mazeppa was presented in October 1876, two months before the orchestral version was played at the Crystal Palace and four months before Bache presented it at his own orchestral concert. The Monthly Musical Record felt "There was ... good reason in introducing [it] as a duet, with a view to familiarizing hearers with it beforehand",[44] and the Musical Standard found that presenting the two-piano arrangement was "an immense help to those who wished to form a correct judgment on it at its first orchestral performance ... as it is impossible, with even the best intentions, to estimate correctly the larger works of Liszt after only one hearing."[45]

Liszt remained grateful to Bache and thanked him on several occasions, writing to him, "Without Walter Bache and his long years of self-sacrificing efforts in the propaganda of my works, my visit to London were indeed not to be thought of."[46]

Liszt 75th birthday celebrations

Bache had long cherished the wish of bringing Liszt to London, which Liszt had last visited in 1841 while still a touring virtuoso, and Liszt knew that whatever standing his music had in that city had in large part to do with Bache's efforts.[47] At least in part to repay the debt he felt he owed Bache, Liszt accepted Bache's invitation to attend celebrations in April 1886 to commemorate Liszt's 75th birthday. These celebrations included the foundation of a Liszt piano scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music, a performance of his oratorio The Legend of Saint Elizabeth led by Alexander Mackenzie in St. James's Hall, an audience with Queen Victoria and a public reception in Liszt's honour at the Grosvenor Gallery.[48] Bache was involved in all four of these events, which were highly successful; by popular demand, Saint Elizabeth had to be repeated at the Crystal Palace.[49]

The Working Men's Society

In the summer of 1867, Bache and Dannreuther formed "The Working Men's Society," a small association to promote the music of Wagner, Liszt and Schumann in England, with Karl Klindworth as an elder statesman for the group. The Society met regularly at one another's homes for the study and discussion of this music. The first study session met in December and consisted of the "Spinning Song" from Wagner's opera The Flying Dutchman, played by Dannreuther in Liszt's piano transcription. At the meeting the next month, the group tackled the first two scenes of Das Rheingold. The meeting which followed featured a reading of Die Walküre. Neither of the latter two works had been presented anywhere; their world premieres at the Munich Court Opera were still two years away. Klindworth's special relationship with Wagner ensured that the group had access to the scores. In the July 1869 meeting, Liszt pupil Anna Mehlig played Liszt's First Piano Concerto for the group.[50] Wagner and Liszt were not the only composers discussed—Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Henselt, Raff and Schumann were among the others whose music was featured. However, the main focus of the group remained the music of Wagner.[51]

Other achievements

Bache became a professor of piano at the Royal Academy of Music in 1881. The foundation of the Liszt Scholarship at that institution in 1886 was mainly due to his efforts.[52] After Bache's death, the name of the scholarship was changed to the Liszt-Bache Scholarship.[53]

Death

Bache died in London in 1888, at the age of 45, after a brief illness. He developed a chill and an ulcerated throat, which "proved too much for his over-worked and highly strung nature."[54] He had otherwise been in good health and had taught his piano students just a couple of days before his death.[55]

Pianism

Technique and repertoire

From his early concerts, Bache was noted for showing thoughtfulness in his interpretations and an excellent pianistic technique.[56] He was especially noted for the evenness and crispness of his scales and the "great delicacy and refinement of feeling" in his playing.[57] Like Hans von Bülow, he was considered an "intellectual" pianist who gave performances that were well executed.[58] He was also considered to have improved with time, becoming a less mercurial and "fidgety" player and that despite occasional exaggerations in his interpretations, his artistry was beyond question.[59]

While he was not the only pianist in England to play Liszt's works, Bache was significant in that he played works in concert for solo piano, two pianos and piano and orchestra.[60] In addition to the two-piano arrangements of the symphonic poems, the first two piano concertos, the B minor piano sonata and the Dante Sonata, Bache played a handful of transcriptions, five of the Hungarian Rhapsodies and a number of smaller-scaled virtuosic works and miniatures which often highlighted "the melodic nature of Liszt's writing".[60] Bache also played a number of works by other composers in his recitals, many of which are unfamiliar today. Grateful for Bülow's assistance in conducting two of his annual concerts, Bache programmed several of the conductor's piano works in his recitals.[61] He also played various works by Mackenzie, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Raff, Silas, Tchaikovsky and Volkmann and more familiar pieces by Bach, Beethoven and Chopin.[62]

Like Bülow, Bache performed works from memory instead of from the printed page, at a time when doing so was a matter of open debate.[63] Also like Bülow, he began giving recitals devoted entirely to the work of one composer. In 1879, he began giving all-Liszt recitals, and in 1883 he experimented with an all-Beethoven recital.[43]

Reception

Bache was considered authoritative in the music of Liszt. About his performance of the B minor piano sonata, the Musical Standard wrote that Bache had made the work his own, giving the impression that Liszt's interpretation of the piece and Bache's were essentially one.[64] However, while Bache's performances were universally acclaimed, the works he chose to play received a mixed reception. The Musical Standard wrote, after a performance of the First Piano Concerto in 1871, that while Bache's playing was excellent, it did nothing to make Liszt's "bizarre" concerto interesting.[65] The Athenaeum wrote about the same performance that while the concerto was intricate, there was no difficulty in following the work as played by Bache.[66]

Bache received praise for the works of other composers, as well. The Musical Standard wrote that he sounded at home with whatever the musical style of the pieces he played.[67] The Musical World noted that Bache's playing of Chopin, Raff, Schumann and Weber all showed "true artistic spirit and taste".[68] Bache's playing of Bach was singled out for mention, with the Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue "neat and highly finished".[69] Bache was also said to have given a "masterly" performance of the Bach D minor keyboard concerto.[70]

Despite receiving positive reviews for his pianism, Bache's difficulties with the critics on behalf of Liszt's music had a negative backlash on his performing career. He was never invited to play with the Philharmonic Society, even after Liszt personally recommended him as a soloist.[71] After printed inquiries by the Musical Standard, which openly questioned why Bache's career had not advanced despite his obvious talent, he was invited in 1874 to play at the Crystal Palace.[72] While his playing was lauded, his choice of music (the Liszt arrangement of Weber's Polonaise Brillante for piano and orchestra) was derided as astoundingly impudent.[73] He also appeared at concerts led by Hans Richter, as organist in Liszt's symphonic poem Die Hunnenschlacht and as pianist in Beethoven's Choral Fantasy and Chopin's Second Piano Concerto.[72]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Walker (2005), 107.

- ↑ Bache, 130.

- ↑ Quoted in Bache, 132.

- ↑ Carley, 14.

- ↑ Bache, 131.

- 1 2 3 4 Allis (2007), 194.

- ↑ Bache, 132; Walker (2005), 107.

- 1 2 Quoted in Bache, 145.

- ↑ Walker (1996), 38.

- ↑ Bache, 152–153.

- ↑ Bache, 153.

- ↑ Walker (1996), 38; (2005), 108.

- 1 2 3 Walker (2005), 108.

- ↑ Quoted in Bache, 156.

- ↑ Quoted in Bache, 157.

- ↑ Walker (1996), 39.

- 1 2 3 Temperley, 1:879.

- ↑ Bache, 161.

- ↑ Bache, 157.

- 1 2 Walker (2005), 109.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allis (2007), 195.

- ↑ Bache, 162, 174.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 106.

- ↑ Bache, 206; Walker (2010), 184–185, footnote 7.

- ↑ Quoted in Bache, 163.

- ↑ Baker, 103.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 108–109.

- 1 2 Bache, 185; Walker (2005), 111.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 111.

- 1 2 Allis (2006), 56.

- 1 2 3 4 Walker (2005), 112.

- 1 2 3 Allis (2007), 196.

- ↑ The Athenaeum (8 July 1865). Quoted in Bache, 189.

- 1 2 Temperley, 1:879–880.

- ↑ Bache, 322–324.

- 1 2 3 Allis (2006), 58.

- ↑ Brown and Stratton, 21.

- 1 2 Walker (2005), 115.

- ↑ Quoted in Walker (2005), 111.

- ↑ Quoted in Walker (2005), 116.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 116.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 114.

- 1 2 Allis (2007), 212.

- ↑ Monthly Musical Record, 6 (December 1876): 194. Quoted in Allis (2006), 63–64.

- ↑ Musical Standard, 10 November 1877, 291. Quoted in Allis (2006), 64.

- ↑ Liszt, 2:478.

- ↑ Walker (1996), 477.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 119.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 121, 123.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 115–116.

- ↑ Bache, 199.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 122.

- ↑ Bache, 320.

- ↑ Bache, 317–318.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 126.

- ↑ The Musical Times, 12 (1865): 117; Monthly Musical Record, 7 (1877): 196; and The Musical Times, 23 (1882): 664. Quoted in Allis (2007), 196.

- ↑ Musical World, 53 (1875): 749 and Musical Standard, (10 November 1877): 291. Quoted in Allis (2007), 196.

- ↑ Allis (2006), 64.

- ↑ The Athenaeum (2 November 1878): 571. Quoted in Allis (2007), 196.

- 1 2 Allis (2007), 197.

- ↑ Allis (2007), 205.

- ↑ Allis (2007), 206.

- ↑ Allis (2007), 214.

- ↑ Wyatt-Smith, Blanche Fanny, Musical Standard (27 October 1883): 256. Quoted in Allis (2007), 197.

- ↑ Musical Standard, (3 June 1871): 54. Quoted in Allis (2007), 197.

- ↑ The Athenaeum, (3 June 1871): 695. Quoted in Allis (2007), 197.

- ↑ Musical Standard, (6 November 1875): 306. Quoted in Allis (2007), 205.

- ↑ Musical World, 51 (1873): 817. Quoted in Allis (2007), 205.

- ↑ The Musical Times, 22 (1881): 186. Quoted in Allis (2007), 212.

- ↑ Musical Standard, (31 October 1874): 273. Quoted in Allis (2007), 212.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 118, 124.

- 1 2 Allis (2007), 215.

- ↑ Walker (2005), 117.

References

- Allis, Michael, "Promotion Through Performance: Liszt's Symphonic Poems in the London Concerts of Walter Bache." In Europe, Empire and Spectacle in Nineteenth-Century British Music, ed. Rachel Cowgill and Julian Rushton (Burlington: Ashgate, 2006). ISBN 0-7546-5208-4.

- Allis, Michael, "'Remarkable force, finish, intelligence and feeling': Reassessing the Pianism of Walter Bache." In The Piano in Nineteenth-Century British Culture: Instruments, Performers and Repertoire, ed. Therese Marie Ellsworth and Susan Wollenberg (Burlington: Ashgate, 2007). ISBN 0-7546-6143-1.

- Bache, Constance, Brother Musicians: Reminiscences of Edward and Walter Bache (London: Methuen & Co., 1901). ISBN 1-120-26866-4.

- Baker, James M., "A Survey of the Late Piano Works." In The Cambridge Companion to Liszt, ed. Kenneth Hamilton (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-521-64462-3 (paperback).

- Brown, James Duff, and Stephen Samuel Stratton, British Musical Biography: A Dictionary of Musical Artists, Authors, and Composers Born in Britain and Its Colonies (London: S.S. Stratton, 1897). ISBN 1-4365-4339-8.

- Carley, Lionel, Edvard Grieg in England (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2006). ISBN 1-84383-207-0.

- Liszt, Franz, col. La Mara and trans. Constance Bache, Letters of Franz Liszt, Volume 2: From Rome to the End (Charleston: BiblioLife, 2009). ISBN 0-559-12774-X.

- Temperley, Nicholas, "Bache. English family of musicians. – (2) Walter Bache." In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), 20 vols. ISBN 0-333-23111-2

- Walker, Alan, Franz Liszt, Volume 3: The Final Years, 1861–1886 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-394-52540-X.

- Walker, Alan, Reflections on Liszt (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-8014-4363-6.

- Walker, Alan, Hans von Bülow: A Life and Times (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). ISBN 0-19-536868-1.