| Vietnamese clothing Trang phục Việt Nam | |

|---|---|

A woman from Northern Vietnam wearing an áo tứ thân, a common dress in the north. | |

A woman from Southern Vietnam wearing an áo bà ba, a common dress in the south. | |

| Vietnamese name | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | Trang phục Việt Nam Quần áo Việt Nam Việt phục |

| Hán-Nôm | 裝服越南 裙襖越南 |

| Chữ Hán | 越服 |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Vietnam |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Vietnamese clothing is the traditional style of clothing worn in Vietnam by the Vietnamese people. The traditional style has both indigenous and foreign elements due to the diverse cultural exchanges during the history of Vietnam. This all eventually led to the birth of a distinctive Vietnamese style of clothing, including the birth of the unofficial national dress of Vietnam, the áo dài.

For daily wear in Vietnam, Vietnamese people just wear normal everyday clothing (đồ Tây; Western clothing), but the common name for everyday clothing is quần áo thường ngày (literally "normal day clothing").

History

The clothing and textile history of Vietnam reflects the culture and tradition that has been developed since the ancient Bronze Age wherein people of diverse cultures were living in Vietnam, the long influence of the Chinese and their associated cultural influence, as well as the short-lived French colonial rule.[1]: 9 The dynamic cultural exchanges which took place with those foreign cultural influences had a significant impact on the history of clothing in Vietnam; this has eventually lead to the birth to a distinctive Vietnamese clothing style, the áo dài is only one of such clothing for example.[1]: 9 Moreover, as Vietnam has multiple ethnicities, there are many distinctive styles of clothing which reflect their wearer's ethnicity.[1]: 20

Since the ancient times, textiles used and produced in Vietnam have been silk in Northern Vietnam, barkcloth, and banana fiber cloth; kapok and hemp were also generally used prior to the introduction of cotton.[1]: 1–2, 17

For at least a thousand years, Vietnam was ruled by the Chinese in the north while the south of Vietnam was ruled by the Indian-culture influenced, independent kingdom of Champa.[1]: 1–2 During this period, the clothing styles which were developed in Vietnam contained both indigenous and imported foreign elements; the upper classes tended to be more easily influenced by those foreign influences than the common people.[1]: 1–2 The upper classes of Vietnam in Northern Vietnam tended to wear clothing which mirrored and was influenced by the fashions of the Chinese, and this style of clothing persisted even after the end of the Chinese rule in the independent kingdom of Đại Việt and in Champa.[1]: 1–2

For centuries, peasant women typically wore a halter top (yếm) underneath a blouse or overcoat, alongside a skirt (váy or quần không đáy). It was until the 1920s in Vietnam's north area in isolated hamlets where skirts were worn.[2] Before the Nguyễn dynasty, the cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt) was worn popularly.[3][4]: 295

Bách Việt period (1000 BC - 1 BC)

Most of ancient northern Vietnam was referred as the Lạc Việt which was considered to be part of the Baiyue region in ancient Chinese texts.[1]: 26 Prior to the Chinese conquest, the Tai nobles first came in Northern Vietnam during the Đông Sơn era, and they started to assimilate the local Mon-Khmer and Kra-dai people in a processed referred as Tai-ization or Tai-ification as the Tai people were politically and culturally dominant in Baiyue; this led to the adoption of the Tai people's clothing and the formation of dress style influenced by the Tai people.[1]: 20, 26

The Han Chinese referred to the various non-Han "barbarian" peoples of North Vietnam and Southern China as "Yue" (Việt) or Baiyue, saying they possessed common habits like adapting to water, having their hair cropped short and having tattoos.[5][6]

Statue of a man with Yue-style short hair and tribal body tattoos, from the state of Yue among the non-Chinese Baiyue peoples of southern China and north Vietnam.

Statue of a man with Yue-style short hair and tribal body tattoos, from the state of Yue among the non-Chinese Baiyue peoples of southern China and north Vietnam.

Nanyue

Nanyue (204 BC–111 BC) was an independent state which was founded by a Chinese general.[7] However, in the Kingdom of Nanyue, it was the elite who were primarily influenced by Chinese clothing as the presence of the Chinese was limited.[1]: 21 The clothing of the elites of Nanyue was mixed of Tai and Chinese clothing styles.[1]: 50 The clothing of the Elites include Chinese fashion from the Warring States period and the Qin dynasty; the style of clothing was mainly a V-shaped collar gown which was tight fitting that was folded to the right.[1]: 50 The clothing was multi-layered; it was common to wear three layers of clothing and tended to have narrow and straight sleeves.[1]: 50 The elites women on the other-hand tended to wear a blouse and a skirt.[1]: 50

Chinese Conquest Period of Vietnam

The Kingdom of Nanyue (204 BC–111 BC) was conquered and colonized by the Han Chinese under the Han dynasty in 111 BC.[7] The Chinese ruled over Northern Vietnam for 1000 years until c. 900 AD.[7][1]: 21 This time, it was the Chinese which lead to acculturation process referred as Sinicization.[1]: 21 The clothing of officials in Northern Vietnam followed the regulations of the Chinese dress.[1]: 50 However, even during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), there was still very little Chinese migration into Northern Vietnam.[1]: 21 It was in the subsequent centuries after the fall of the Han dynasty that there was a large influx of Chinese in the region of Annan.[1]: 21

From period of 43 AD to 939 AD, the direct rule of the Chinese in Northern Vietnam led to the Chinese clothing influence on the local clothing styles, especially the local elites; this also included the leaders who rebelled against the rule of the Chinese who typically wore Chinese-style clothing.[1]: 50 The Elites wore clothing made of silk which were colourful and decorated while commoners wore plain hemp-based clothing.[1]: 50 According to the Book of the Later Han by Fan Ye, the civilization of Lingnan started with Ren Yan and Xi Guang (both Han Officials in Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen respectively) who were credited for introducing hats and sandals to the people of Lingnan along with many other aspects, such as agriculture.[4]: 25

Non-Chinese immigrants were attracted to the Tang dynasty-ruled Annan, and non-Chinese migrants started settling in the neighbouring areas; the blending of Chinese culture, Mon-Khmer, and Tai-Kradai in northern Vietnam led to the development of the national majority, the Vietnamese people.[1]: 21 The elites followed the Chinese clothing system more closely once the regions had been incorporated into the Chinese imperial system.[1]: 21 During the thousand years of colonization, the Vietnamese adopted Chinese clothing, but local customs and styles yet were not assimilated and lost.[7]

Lý dynasty to Trần dynasty (1009–1400)

After Northern Vietnam became independent from China, the Vietnamese elites both followed the Chinese fashions and created distinctive, but still heavily Chinese-influenced local Vietnamese styles.[1]: 21 The Chinese style dress gradually spread to Vietnamese commoners and among the people who were living in the surrounding regions which was being formally ruled by the Vietnamese; however, the form of the commoner clothing were distinct from those worn by the elite class.[1]: 21 Almost all male commoners of the Việt ethnic and ethnic minorities started to wear Chinese style trousers and shirts.[1]: 21

Vietnamese wore a round neck costume, which was made from 4 parts of cloth called áo tứ điên.[8] Both men and women wore it. There are also other types such as: áo tràng vạt (long-flap robe). The garments "áo" (áo is for the upper part of body) are below knee length, and round neck garments have buttons when the long-flap robe is tied to the right.

Short hair or a shaven head was popular in Vietnam since the ancient period. Vietnamese men had shaven head or short hair during Trần dynasty.[9] This can be seen in the painting "The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains" which portrayed Emperor Trần Nhân Tông and his men during the Trần dynasty[10] as well as the Chinese encyclopedia "Sancai Tuhui" from 17th century. The convention was popular until the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam.

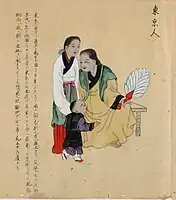

Vietnamese in Sancai Tuhui: short hair, wearing áo tứ điên (left) and loincloth (right)

Vietnamese in Sancai Tuhui: short hair, wearing áo tứ điên (left) and loincloth (right) Trần dynasty clothing as depicted in "The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains".

Trần dynasty clothing as depicted in "The Mahasattva Trúc Lâm Coming Out of the Mountains".

Hồ dynasty (1400–1407)

In 1400s, Emperor Lê Quý Ly wrote a poem to describe his country and his government to the Ming dynasty envoys, explaining shared cultural status between Đại Ngu and Ming by referring to the Han and Tang dynasties during a time when Đại Việt was a part of China, "You inquire about the state of affairs in Annan. Annan’s customs are simple and pure. Moreover, official clothing is according to the Tang system. The rites and music that control intercourse between the ruler and the officials are those of the Han [...]".[4]: 72

Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam (1407–1427)

When the Han Chinese ruled the Vietnamese in the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, due to the Ming dynasty's conquest during the Ming–Hồ War they imposed the Han Chinese style of men wearing long hair on short-haired Vietnamese men. The Vietnamese were ordered to stop cutting their hair and instead to grow their hair long and switch to Han Chinese clothing within a month by a Ming official. Ming administrators said their mission was to civilize the unorthodox Vietnamese barbarians.[11] Women had to wear Chinese style clothing.[12]: 528 The Ming dynasty only wanted the Vietnamese to wear long hair and to stop teeth blackening so they could have white teeth and long hair like Chinese.[13]: 110

An old Kinh lady with blackened teeth (nhuộm răng đen).

An old Kinh lady with blackened teeth (nhuộm răng đen). A picture from the book, Technique du peuple Annamite (Vietnamese: Kỹ thuật của người An Nam), depicting the Vietnamese custom of teeth blackening. It has chữ Nôm, 染𦝄 and Vietnamese alphabet, Nhuộm răng.

A picture from the book, Technique du peuple Annamite (Vietnamese: Kỹ thuật của người An Nam), depicting the Vietnamese custom of teeth blackening. It has chữ Nôm, 染𦝄 and Vietnamese alphabet, Nhuộm răng.

Later Lê dynasty (1428–1789)

In 1435, Nguyễn Trãi, a scholar official, and his colleagues compiled the Geography (Dư địa chí) based on the lessons he had taught to the prince, who then became Emperor Lê Thái Tông; his teachings also included how Vietnamese were different from their neighbours in terms of language and clothing customs: "The people of our land should not adopt the languages or the clothing of the lands of the Wu [Ming], Champa, the Lao, Siam, or Zhenla [Cambodia], since doing so will bring chaos to the customs of our land".[4]: 138 [13]: 82 They viewed the Ming as having been affected by Mongolian customs in terms of clothing customs (e.g. with their hair hanging down the back, white teeth, short clothing, long sleeves, and bright and lustrous robes and caps) despite returning to the ways of Han and Tang and the people of Lao as wearing Indian-style clothing like the robes of Buddhist monks "like the irrigated fields of dysfunctional families".[4]: 138 [13]: 82 Therefore, they considered that all those styles, including those of Champa and Khmer, should not be worn as they disregarded the customs of the Vietnamese, who continued to follow the rites of Zhou and Song dynasties: in the Dư địa chí, it is written that according to the scholar Lý Tử Tấn, during the reign of Trần Dụ Tông, Emperor Taizu of Ming bestowed a poem saying, "An Nan [Đại Việt] has the Trần clan, and its customs are not those of the Yuan [Mongols]. Its clothing and caps are in the classic pattern of the Zhou dynasty. Its rites and music follow the relationship between ruler and minister, as in the Song dynasty” and therefore Emperor Taizu promoted the ambassador of Đại Việt (Đoàn Thuận Thân) by 3 ranks to be equal that of Joseon.[4]: 138

The Lê dynasty encouraged the civilians to return to traditional customs: teeth blackening as well as short hair or shaved heads. A royal edict was issued by Vietnam in 1474 forbidding Vietnamese from adopting foreign languages, hairstyles and clothes like that of the Lao, Champa or the "Northerners" which referred to the Ming. The edict was recorded in the 1479 Complete Chronicle of Đại Việt of Ngô Sĩ Liên.[4]: 87

Two women and a child in Tonkin around the 1700s.

Two women and a child in Tonkin around the 1700s.

Revival Lê dynasty

The dragon robe (áo Long Bào) was worn in Vietnam since the Restored Late-Lê period, Phan Huy Chú wrote in the Categorized Records of the Institutions of Successive Dynasties (Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí):[14]

"Since the Restored Later-Lê era, for grand and formal occasions, (the emperors) always wore Xung Thiên hat and Long Bào robe...."

Through many portraits and images of rulers during the Ming, Joseon, and more recently, during the Nguyễn dynasty, one could see that this standard (the wearing of Long Bào) existed for a long period of time within a very large region.[14]

Đàng Trong and Đàng Ngoài

Before 1744, people of both Đàng Ngoài (Tonkin) and Đàng Trong (Cochinchina) wore áo tràng vạt with a thường (a kind of long skirt; 裳). The tràng vạt dress appeared very early on in Vietnamese history, possibly during the first Chinese domination by Eastern Han, after Ma Yuan was able to finally defeat the Trưng Sisters’ rebellion. Those of the lower classes would prefer sleeves with reasonable widths or tight sleeves, and of simple colors. This stemmed from its flexibility in work, allowing people to move around with ease.[14] Both male and female had loose long hair.

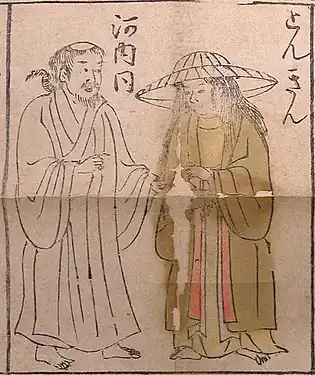

A servant woman and a mandarin of the Lê dynasty.

A servant woman and a mandarin of the Lê dynasty. Clothing of people of Đàng Trong, 1675.

Clothing of people of Đàng Trong, 1675. Clothing of people of Đàng Ngoài, 1645.

Clothing of people of Đàng Ngoài, 1645. Portrait of Nguyễn Quý Đức in Đàng Ngoài. He was wearing a cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt) and had loose long hair.

Portrait of Nguyễn Quý Đức in Đàng Ngoài. He was wearing a cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt) and had loose long hair. Portrait of Prince Tôn Thất Hiệp (Nguyễn Phúc Thuần) of Đàng Trong from the 17th century. He wears a cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt).

Portrait of Prince Tôn Thất Hiệp (Nguyễn Phúc Thuần) of Đàng Trong from the 17th century. He wears a cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt). Portrait of Lady Minh Nhẫn Mrs. Bùi Thị Giác (1738-1805), Thai Binh province of Đàng Ngoài in Revival Lê dynasty.

Portrait of Lady Minh Nhẫn Mrs. Bùi Thị Giác (1738-1805), Thai Binh province of Đàng Ngoài in Revival Lê dynasty.

The Nguyễn lords were key players in promoting Chinese-influenced clothing in Central and Southern Vietnam where they expanded their territories and extended control over all the territories which used to be ruled by Champa and the Khmer Empire.[1]: 73 While expanding their territories, Vietnamese people immigrated to the south and the Nguyễn lords allowed Ming dynasty Chinese refugees to settle in those areas, thus creating a mixed society which was composed of Vietnamese, Chinese, and Cham peoples.[1]: 73 Both Vietnamese and the Chinese brought their own clothing style in Đàng Trong (Huế) and continued to wear their clothing until a proclamation by Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát who decreed that all the people under his rule had to changed their clothing into Ming-influenced Chinese clothing in order to make his people dressed differently from those under the rule of the Trịnh lords.[1]: 73 As a result, the gown and skirt which was worn by the Vietnamese and which was common in the north was replaced by trousers and gown with Chinese-influenced fasteners; this new form of clothing was described by Lê Quý Đôn as the predessor to the áo dài, the áo ngũ thân which was composed of a 5-piece gown.[1]: 73 In 1744, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of Đàng Trong (Huế) both men and women at his court wear trousers and a gown with buttons down the front. The members of the Đàng Trong court (southern court) were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Đàng Ngoài (Hanoi),[15][4]: 295 who wore áo tràng vạt with long skirts.[1]: 72

- Paintings about Đàng Ngoài

"Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Scholars and students wear cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt). Adults have loose and long hair.

"Giảng học đồ" (講學圖 - Teaching): Scholars and students wear cross-collared robe (áo tràng vạt). Adults have loose and long hair.

Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1945)

During unified period of Vietnam, the people in the northern and southern regions of Vietnam (i.e. previously Champa) continued to wear their local ethnic clothing.[1]: 1–2 In the Southern regions, the people continued to wear their local clothing and became increasingly similar whereas in the northern regions, the clothing worn was very varied.[1]: 1–2 When the Vietnamese started to assimilate the majority of the Cham and the Khmer Krom living in their new conquered southern territories; and the Vietnamese-ification of the Cham and the Khmer Krom lead to them adopting Vietnamese style clothing while at the same time retaining several distinctive ethnic elements.[1]: 21

Áo ngũ thân (predecessor of the current áo dài, which made of 5 parts) with standing collar and trousers was forced on Vietnamese people by the Nguyễn dynasty. Skirts (váy) were banned due to Emperor Minh Mệnh's extreme Neo-Confucianism.[16] However, it was up to the 1920s in Vietnam's north area in isolated hamlets where skirts were worn.

The Vietnamese had adopted the Chinese political system and culture during the 1,000 years of Chinese rule, but after the Qing conquest of China, Han Chinese were forced to adapt to Manchurian customs like wearing a queue. So the Vietnamese viewed their surrounding neighbors like Khmer and the Han Chinese under the Qing dynasty as barbarians and themselves as a small version of China (the Middle Kingdom) who still maintained Han culture (civilised culture).[17] By the Nguyễn dynasty, the Vietnamese themselves were ordering the Khmer to adopt Han Chinese culture by ceasing "barbarous" habits like cropping hair and ordering them to grow it long besides making them replace skirts with trousers.[18]

Áo tràng vạt was still worn during Nguyễn dynasty. Other styles of clothing were also created during this time such as the áo nhật bình and the áo tấc (formal wear for rituals and formal occasions).

The áo dài was created when tucks which were close-fitting and compact were added in the 1920s to the áo ngũ thân. The Chinese-influenced clothing in the form of trousers and tunic were mandated by the Nguyễn dynasty. The Chinese Ming dynasty, Tang dynasty, and Han dynasty clothing was referenced in order to be adopted by the Vietnamese military and bureaucrats by the Nguyễn Lord, Nguyễn Phúc Khoát (Nguyễn Thế Tông) from 1744.[4]: 295

- Imperial and noble clothing

Clothing of Emperor Khải Định.

Clothing of Emperor Khải Định. Empress Nam Phương wearing an áo nhật bình and khăn vành dây.

Empress Nam Phương wearing an áo nhật bình and khăn vành dây. Princess Mỹ Lương wearing an áo nhật bình and khăn vành dây.

Princess Mỹ Lương wearing an áo nhật bình and khăn vành dây. Vietnamese ambassadors in Paris wearing traditional formal clothing.

Vietnamese ambassadors in Paris wearing traditional formal clothing. Nguyễn dynasty mandarins dressed in formal wear.

Nguyễn dynasty mandarins dressed in formal wear. The mandarin uniform of Nguyễn Tri Phương. His uniform shows that he is a sixth ranked mandarin (quan viên lục phẩm).

The mandarin uniform of Nguyễn Tri Phương. His uniform shows that he is a sixth ranked mandarin (quan viên lục phẩm).

- Artifacts of Nguyễn dynasty

Imperial headgear "Mũ Xung Thiên"

Imperial headgear "Mũ Xung Thiên" Court attires of the Nguyễn dynasty

Court attires of the Nguyễn dynasty Ceremonial dress of Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương[lower-alpha 1]

Ceremonial dress of Marshall Nguyễn Tri Phương[lower-alpha 1] Student uniforms of the imperial academy

Student uniforms of the imperial academy 19th century Phốc Đầu cap, with ornamented gold Kim Bác Sơn

19th century Phốc Đầu cap, with ornamented gold Kim Bác Sơn Mandarin boots and shoes. Gilded metal, Nguyễn dynasty, 19th-early 20th century[lower-alpha 2]

Mandarin boots and shoes. Gilded metal, Nguyễn dynasty, 19th-early 20th century[lower-alpha 2] Gilded metal hat, Nguyễn dynasty, 19th-early 20th century. Object for worship

Gilded metal hat, Nguyễn dynasty, 19th-early 20th century. Object for worship A mũ cánh chuồn made out of metal and horse hair during the 19th century, Nguyễn dynasty.

A mũ cánh chuồn made out of metal and horse hair during the 19th century, Nguyễn dynasty.

- Common outfits of the Nguyễn dynasty

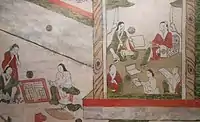

_(14580626259).jpg.webp) A painting depicting traditional clothing during the Nguyễn dynasty.

A painting depicting traditional clothing during the Nguyễn dynasty. A northern Vietnamese girl with black teeth sitting on a chair.

A northern Vietnamese girl with black teeth sitting on a chair. A northern Vietnamese girl smiling.

A northern Vietnamese girl smiling. A picture depicting traditional wedding costumes.

A picture depicting traditional wedding costumes.

Twentieth century

From the twentieth century onward, Vietnamese people began wearing Western clothing due to modernisation and French influence. The áo dài was briefly banned after the fall of Saigon, but was reintroduced back into the scene.[19] It is worn in white by high school girls, often as part of school uniform in Vietnam. It is also worn by female receptionists and secretaries. Styles can differ in Northern and Southern Vietnam.[20] The most popular type of Vietnamese clothing today, is the áo dài for men and women, and suits or sometimes áo gấm (modified áo dài) for men.

Two women wearing áo dài walking in Saigon, 1947.

Two women wearing áo dài walking in Saigon, 1947. Two women in áo dài chatting.

Two women in áo dài chatting. A man wearing an áo dài

A man wearing an áo dài

Twenty-first century

In the 21st century, some companies and individuals are working on reviving, preserving, and upholding Vietnamese traditional culture, including Vietnamese clothing and designs. In 2013, researcher Trần Quang Đức published the book Ngàn năm áo mũ, marking the first step in restoring traditional costumes in Vietnam. Currently, there are many companies that research and reproduce traditional Vietnamese clothing, for example, a company called Ỷ Vân Hiên started to provide tailoring services of ancient Vietnamese clothing which included the áo ngũ thân and áo tràng vạt.[21] Ỷ Vân Hiên company largely reproduces clothing worn in the Nguyễn dynasty period.[22] Other tailoring companies, such as Trần Thị Trang's company specializes in making ancient Vietnamese clothing which was typically worn between the Ngô dynasty and the Nguyễn dynasty.[23] Painter Cù Minh Khôi and his friends launched the Hoa Văn Đại Việt project which digitized 250 ancient Vietnamese decorative patterns which spanned from the Lý dynasty to Nguyễn dynasty and applied them to variety of modern products such as keychains, calendars, T-shirts, and lucky money packets.[21]

In 2018, a book called Dệt Nên Triều Đại in Vietnamese language and Weaving a Realm in English language was published by the Vietnam Centre, an independent, non-government and non-profit organization which aims to promote Vietnamese culture to the world.[24] The book contained historical facts about ancient Vietnamese fashion, illustrations and photos.[25] The book Dệt Nên Triều Đại only covers the early years of the Later Lê era's clothing traditions from 1437 to 1471 AD after the Ming dynasty's forces were defeated by Emperor Lê Lợi.[25]

In 2008, there was a festival in Huế, where the Nam Giao ceremony[26] was performed again after being revived again for the first time in 2004. Traditional clothing was worn during the ceremony and highlighted the clothing worn during the Nguyễn dynasty (however, some of the clothing of the Nguyễn dynasty in this event are still inaccurate).

A parade in front of the Huế citadel.

A parade in front of the Huế citadel. People in formal mandarin official uniforms walking in a parade.

People in formal mandarin official uniforms walking in a parade. A man playing as the role of the emperor, wearing traditional clothing for the ritual.

A man playing as the role of the emperor, wearing traditional clothing for the ritual. Mandarins sitting uptop chairs while royal guards hold umbrellas.

Mandarins sitting uptop chairs while royal guards hold umbrellas. The procession of the emperor going towards the ritual altar.

The procession of the emperor going towards the ritual altar. Musicians of the royal court playing traditional court music (nhã nhạc).

Musicians of the royal court playing traditional court music (nhã nhạc). Reenactment of the moment that Emperor Quang Trung ascended the throne atop Bân mountain (Núi Bân).

Reenactment of the moment that Emperor Quang Trung ascended the throne atop Bân mountain (Núi Bân).

Types of clothing

Áo dài

.jpg.webp)

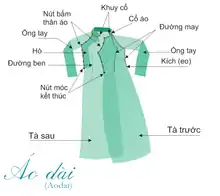

The áo dài is considered to be the traditional Vietnamese national garment. Besides suits and dresses nowadays, men and women can also wear áo dài on formal occasions. It is a long, split tunic worn over trousers. Áo translates as shirt and dài means "long". The outfit was derived from its predecessor, the áo ngũ thân, a five piece outfit that was worn in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The male version of áo dài or modified áo dài are also worn during weddings or formal occasions. The áo dài can be paired with the nón lá or the khăn vấn.

Parts of the outfit

- Tà sau: back flap

- Nút bấm thân áo: hooks used as fasteners and holes

- Ống tay: sleeve

- Đường bên: inside seam

- Nút móc kết thúc: main hook and hole

- Tà trước: front flap

- Khuy cổ: collar button

- Cổ áo: collar

- Đường may: seam

- Kích (eo): waist

Khăn vấn

Khăn vấn or khăn đóng is a kind of turban traditionally worn by Vietnamese people. The word vấn means coil around. The word khăn means cloth, towel or scarf. It is typically worn with other outfits, most often the áo dài. The Nguyễn Lords introduced the predecessor to the áo dài, the áo ngũ thân. It was traditionally worn with a handwrapped turban. The members of the Đàng Trong court (southern court) were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Đàng Ngoài, who wore áo tràng vạt with long skirts and loose long hair. Hence, wrapping scarf around head became a unique custom in the south then. From 1830, Minh Mạng emperor force every civilian in the country to change their clothes, that custom became popular in the all of Vietnam.

A bride and a groom wearing khăn vấn on their wedding.

A bride and a groom wearing khăn vấn on their wedding. Vietnamese women wear a version of áo Nhật bình with khăn vấn.

Vietnamese women wear a version of áo Nhật bình with khăn vấn.

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

A girl siting in the Huế Citadel wearing the áo dài.

A girl siting in the Huế Citadel wearing the áo dài..jpeg.webp)

Quan họ ensemble all wearing the áo tứ thân.

Quan họ ensemble all wearing the áo tứ thân. Quan họ ensemble wearing traditional clothing.

Quan họ ensemble wearing traditional clothing. A lady wearing an áo yếm

A lady wearing an áo yếm

Examples of garments

- Áo nhật bình - a popular costume for the nobility under the Nguyễn dynasty.

- Áo giao lĩnh - is a type of cross-collared robe that was commonly used throughout all dynasties of Vietnam, but by the Nguyễn dynasty, áo giao lĩnh was only used in rituals. Also known as áo tràng vạt.

- Áo viên lĩnh - Is a type of round neck shirt popular throughout the dynasties of Vietnam, under the Nguyễn dynasty they were still used as vestments for mandarins, emperors, empress, and royal aristocrats.

- Áo tứ điên - is a type of áo viên lĩnh, this costume was popular before the Nguyễn dynasty, especially popular in the Lý and Trần dynasties.

- Áo đối khâm - a type of costume usually worn outside, popular in the Lý - Trần dynasties.

- Áo tứ thân - a four-piece woman's dress widely popular in the North of Vietnam.

- Áo ngũ thân - a dress with five parts, this costume is divided into two types: áo ngũ thân tay chẽn (áo chẽn) and áo ngũ thân tay thụng (áo tấc). In addition, this dress is also the predecessor of the áo dài.

- Khăn mỏ quạ - crow beak scarf is a traditional headscarf of ancient Vietnamese women.

- Áo yếm - woman's undergarment.

- Áo gấm – formal brocade tunic for government receptions, or áo the for the man in weddings.

- Mũ chữ Đinh - It is a type of hat with the shape of the character Đinh (丁), it was worn by officers and middle-class men during the Lê dynasty.

- Mũ Phốc Đầu - formal headwear for the royal court, traditionally mandarin officials wore it. It is derived from the Chinese Futou.

- Nón lá and nón ba tầm (nón quai thao) - traditional hats worn in the south and north of Vietnam.

- Khăn vấn – a type of turban worn by the Vietnamese people from Nguyễn dynasty to the present day.

- Áo tràng Phật tử – typically shortened to "áo tràng" it is a robe worn by Upāsaka and Upāsikā in Vietnamese Buddhist temples.[lower-alpha 3]

- Áo dài – the typical Vietnamese formal dress

- Áo bà ba – two-piece ensemble for men and women[27]

Notes

- ↑ The dress was taken as a trophy by Garnier in the capture of Hanoi in 1873

- ↑ Objects for worship, at the National Museum Vietnamese History

- ↑ Typically light blue but can be found in brown and is similar to the ones worn by Vietnamese Buddhist monastics in regards to the trademark collar similar to the Áo Giao lĩnh but without the sleeves with hidden pockets. While there are matching pants they are not a required part of the outfit for the laity. They are also known as áo giao lĩnh.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Howard, Michael C. (2016). Textiles and clothing of Viet Nam : a history. Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4766-6332-6. OCLC 933520702.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ A. Terry Rambo (2005). Searching for Vietnam: Selected Writings on Vietnamese Culture and Society. Kyoto University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-920901-05-9.

- ↑ T., Van (4 July 2013). "Ancient costumes of Vietnam". VietNamNet Global.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Introduction to Asian Civilizations (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231511100.

- ↑ Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Issue 15. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 1996. p. 94.

- ↑ Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Congress (1996). Indo-Pacific Prehistory: The Chiang Mai Papers, Volume 2. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Vol. 2 of Indo-Pacific Prehistory: Proceedings of the 15th Congress of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5–12 January 1994. The Chiang Mai Papers. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Australian National University. p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 Montero, Darrel (2019). Vietnamese Americans patterns of resettlement and socioeconomic adaptation in the United States. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-00451-9. OCLC 1159420864.

- ↑ Trần, Quang Đức (2013). Ngàn năm áo mũ. Vietnam: Công Ty Văn Hóa và Truyền Thông Nhã Nam. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1629883700.

- ↑ Wang, Qi (1609). Sancai Tuhui. China.

- ↑ 石渠寶笈秘殿珠林續編 (PDF) (in Chinese).

- ↑ The Vietnam Review: VR., Volume 3. Vietnam Review. 1997. p. 35.

- ↑ Columbia chronologies of Asian history and culture. John Stewart Bowman. New York: Columbia University Press. 2000. ISBN 0-231-50004-1. OCLC 51542679.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 3 Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam : Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-107-12424-0. OCLC 922694609.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 Organization, Vietnam Centre (2020). Weaving a Realm (Dệt Nên Triều Đại). Vietnam: Dân Trí Publisher. ISBN 978-604-88-9574-7.

- ↑ Tran, My-Van (2005). A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan: Prince Cuong De (1882–1951). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415297165.

- ↑ Woodside, Alexander (1988). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 134. ISBN 9780674937215.

- ↑ Chanda, Nayan (1986). Brother Enemy: The War After the War (illustrated ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 53, 111. ISBN 9780151144204.

- ↑ Chandler, David (2018). A History of Cambodia (4 ed.). Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-0429964060.

- ↑ Vo, Nghia M. (2011). Saigon: A History. McFarland. p. 202. ISBN 9780786464661.

The new government banned the wearing of the traditional áo dài. Their income from sewing áo dài suddenly plummeted, forcing them to sell everything to survive: refrigerator, radio, food, and clothing. Only after the ban was lifted ten years later

- ↑ Taylor, Philip (2007). Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 157. ISBN 9789812304407.

The contemporary versions of Áo dài are of considerable sociological interest as they represent regional variations, as well as age and gender arrangements (men rarely wear them nowadays and usually dress in Western-style suits

- 1 2 "Vietnamese youngsters work to retrieve the glory of ancient culture". en.nhandan.vn. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ↑ AGENCY. "The designer making Vietnamese 19th-century outfits fashionable again". The Star. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ↑ "Vietnamese woman revives country's ancient clothes". Tuoi Tre News. 8 October 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ↑ "Home | Vietnam Centre - Bring Vietnam To You". Vietnam Centre. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- 1 2 "Weaving a Realm: Documenting Vietnam's Royal Costumes From the 15th Century | Saigoneer". saigoneer.com. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ↑ "Festival Huế 2008: Tôn nghiêm lễ tế Nam Giao". 5 June 2008.

- ↑ Harms, Erik (2011). Saigon's Edge: On the Margins of Ho Chi Minh City. University of Minnesota Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780816656059.

She then left the room to change out of her áo Ba Ba into her everyday home clothes, which did not look like peasant clothes at all. In Hóc Môn, traders who sell goods in the city don "peasant clothing" for their trips to the city and change back

- Nguyễn Khắc Thuần (2005), Danh tướng Việt Nam, Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục.

Sources

- Leshkowich, Ann Marie. "History of Ao Dai".

- Ay-leen (20 October 2010). "The Ao Dai and I: A Personal Essay on Cultural Identity and Steampunk".

External links

![]() Media related to Clothing of Vietnam at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Clothing of Vietnam at Wikimedia Commons