In logic and mathematics, a truth value, sometimes called a logical value, is a value indicating the relation of a proposition to truth, which in classical logic has only two possible values (true or false).[1][2]

Computing

In some programming languages, any expression can be evaluated in a context that expects a Boolean data type. Typically (though this varies by programming language) expressions like the number zero, the empty string, empty lists, and null evaluate to false, and strings with content (like "abc"), other numbers, and objects evaluate to true. Sometimes these classes of expressions are called "truthy" and "falsy" / "false".

Classical logic

| ⊤ | ·∧· | ||

| true | conjunction | ||

| ¬ | ↕ | ↕ | |

| ⊥ | ·∨· | ||

| false | disjunction | ||

| Negation interchanges true with false and conjunction with disjunction. | |||

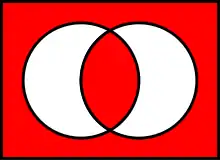

In classical logic, with its intended semantics, the truth values are true (denoted by 1 or the verum ⊤), and untrue or false (denoted by 0 or the falsum ⊥); that is, classical logic is a two-valued logic. This set of two values is also called the Boolean domain. Corresponding semantics of logical connectives are truth functions, whose values are expressed in the form of truth tables. Logical biconditional becomes the equality binary relation, and negation becomes a bijection which permutes true and false. Conjunction and disjunction are dual with respect to negation, which is expressed by De Morgan's laws:

- ¬(p ∧ q) ⇔ ¬p ∨ ¬q

- ¬(p ∨ q) ⇔ ¬p ∧ ¬q

Propositional variables become variables in the Boolean domain. Assigning values for propositional variables is referred to as valuation.

Intuitionistic and constructive logic

In intuitionistic logic, and more generally, constructive mathematics, statements are assigned a truth value only if they can be given a constructive proof. It starts with a set of axioms, and a statement is true if one can build a proof of the statement from those axioms. A statement is false if one can deduce a contradiction from it. This leaves open the possibility of statements that have not yet been assigned a truth value. Unproven statements in intuitionistic logic are not given an intermediate truth value (as is sometimes mistakenly asserted). Indeed, one can prove that they have no third truth value, a result dating back to Glivenko in 1928.[3]

Instead, statements simply remain of unknown truth value, until they are either proven or disproven.

There are various ways of interpreting intuitionistic logic, including the Brouwer–Heyting–Kolmogorov interpretation. See also Intuitionistic logic § Semantics.

Multi-valued logic

Multi-valued logics (such as fuzzy logic and relevance logic) allow for more than two truth values, possibly containing some internal structure. For example, on the unit interval [0,1] such structure is a total order; this may be expressed as the existence of various degrees of truth.

Algebraic semantics

Not all logical systems are truth-valuational in the sense that logical connectives may be interpreted as truth functions. For example, intuitionistic logic lacks a complete set of truth values because its semantics, the Brouwer–Heyting–Kolmogorov interpretation, is specified in terms of provability conditions, and not directly in terms of the necessary truth of formulae.

But even non-truth-valuational logics can associate values with logical formulae, as is done in algebraic semantics. The algebraic semantics of intuitionistic logic is given in terms of Heyting algebras, compared to Boolean algebra semantics of classical propositional calculus.

In other theories

Intuitionistic type theory uses types in the place of truth values.

Topos theory uses truth values in a special sense: the truth values of a topos are the global elements of the subobject classifier. Having truth values in this sense does not make a logic truth valuational.

See also

References

- ↑ Shramko, Yaroslav; Wansing, Heinrich. "Truth Values". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ "Truth value". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d.

- ↑ Proof that intuitionistic logic has no third truth value, Glivenko 1928

External links

- Shramko, Yaroslav; Wansing, Heinrich. "Truth Values". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.