The transmission of hepadnaviruses between their natural hosts, humans, non-human primates, and birds, including intra-species host transmission and cross-species transmission, is a topic of study in virology.

Hepadnaviruses are a family of viruses that can cause liver infections in humans and animals. They are Group VII viruses that possess double-stranded DNA genomes and replicate using reverse transcriptase. This unique replication strategy, combined with their extremely small genomes and a very narrow host and tissue tropism, has distinguished them enough to be classified in the family Hepadnaviridae.[1] There are two recognized genera:

- Orthohepadnavirus, type species: hepatitis B virus (HBV)

- Avihepadnavirus, type species: duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV)

Structure

With the example of human HBV: the particular feature of the HBV structure is the presence of three different forms in the plasma of infected patients:

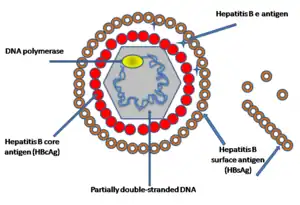

- Dane particle (diameter ≈ 42 nm): the complete virion, which is infectious and consists of an enveloped icosahedral nucleocapsid containing the viral genome, consisting of core protein and protecting the partially double-stranded DNA genome, bounding with DNA polymerase. The capsid is enveloped by a lipid bilayer that contains three forms of envelope proteins: small (S) proteins, intermediated (M) proteins, and large (L) proteins, and these proteins have different surface antigenes domains which contribute the viral infectivity: L protein (Pre S1, Pre S2, S), M protein (Pre S2, S), S protein (S). In figure 1, showing the simplified structure of HBV particles.

- Subviral sphere particles (diameter ≈ 22 nm), these smaller, non-infectious and are the most abundant particle in the blood of an infected one. They are assumed to have the ability of absorbing virus-neutralizing antibodies to facilitate the virus spread and maintenance in the host.[2]

- Filaments (diameter ≈ 22 nm, length: 50 nm-70 nm), which are less known about, but they are actually consisted of many subviral sphere particles.

Genome

As with the example of HBV, showing in figure 2, four open reading frames are encoded (ORFs), all ORFs are in the same direction, defining the minus- and plus-strands. And the virus has four known genes, which encode the core protein, the virus polymerase, surface antigens (preS1, preS2, and S) and the X protein. The minus-strand DNA is complete and spans the entire genome, while the plus strand spans only about two-thirds of the genome length and have variable 3' ends. But for the avihepadnaviruses they normally extend plus-strands almost all the way to the modified 5' end.[1] The minus-strand is linked to the viral reverse transcriptase and can encode all the known viral proteins, but the plus-strain cannot encode viral proteins.

Replication

With the example of HBV: the mechanisms of infecting hepatocytes are still not well understood, but among the studies, it was revealed that the PreS1 domain of the L protein, plays a critical role in the infection, thus exhibiting different host specificity between different hepadnaviruses. Figure show the general process of the HBV infecting host cell: attachment-entry-uncoating-replicate-assembly-release. About the viral entry, several proteins have been identified as possible virus receptors, and studies show that the binding of virion with receptors can be neutralized by anti-PreS1 antibodies.

The replication is the unique reverse transcriptase strategy: after uncoating, nucleocapsids are transported to the host cell nucleus, the virion DNA will be converted into covalently closed circular (CCC) DNA, the template for the transcription of the viral RNAs. Then undergoes transcription by the host cell RNA polymerase and the transcript is translated by host cell ribosomes;[1] the high capacity of this replicating part contributes many errors which may help the virus adapt to the host.

New virus particles are formed, which acquire lipid from the endoplasmic reticulum of the host cell, and the genome is packaged within these particles, which then bud off from the cell; and some part of the new genome may return to the host cell nucleus for replication more genomes.

Phylogenetic tree

All the members of family hepadnaviridae share remarkable similarities in the genome organization and the replication strategies, however, it also shows the differences between different species, different genotypes, and different subtypes. The species specificity of them are determined, to some extent, at the level of virus entry, involving the PreS1 part of the large envelop protein L, which could be a reason for their specificity of host range.

Orthohepadnavirus

Viruses in this genus infect mammals, including human, apes, and rodents, with a narrow host range for each virus. The only known natural host for HBV is human, chimpanzees maybe infected experimentally. The orthohepadnaviruses have been divided into four distinct species, with HBV (human hepatitis B virus), WHV (woodchuck hepatitis virus), GSHV (ground squirrel hepatitis virus ), and WMHBV (woolly monkey hepatitis B virus) as the prototypes, based on the host range from a limited number of studies. From the result of molecular studies about the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays, information about the number and geographic distribution of HBV genotypes and naturally occurring HBV mutants are gained. Eight HBV genotypes, A to H, have been identified in human and three closely related genotypes in apes are found, like gibbon, orangutan, chimpanzee; and he eight HBV genotypes have further diverged into at least 24 subgenotypes.[3] With different analysis, including analysis of recombinants, the new Genotype J was provisionally assigned to be a genetic variant of HBV which is divergent from known human and ape genotypes, it was isolated from a Japanese patient.[4]

Avihepadnavirus

Viruses in this genus exclusively infect birds; duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) and heron hepatitis B virus (HHBV) are the prototypes. Avihepadnaviruses have been detected in various duck species. As the same with the orthohepadnaviruses, avihepadnaviruses have a rather narrow host range, but its common host are ducks and geese, other possible hosts are herons, stocks and crane.[3]

Differences between orthohepadnaviruses and avihepadnaviruses

- Low nucleotide sequence identity

- Differences in genome size, with genomes of orthohepadnaviruses generally larger than that of avihepadnaviruses

- Larger core proteins and no M surface for avihepadnaviurses; for orthohepadnaviruses, virions and filaments are enriched in L proteins and empty spheres consist predominantly of S proteins, while for duck hepatitis B virus, L and S proteins are distributed evenly between particle types[1]

- Different host range restrictions (exclusively mammals for orthohepadnaviruses and exclusively birds for avihepadnaviruses)

- Different predominant transmission strategies (horizontal transmission for orthohepadnaviruses and vertical transmission for avihepadnaviruses)

Transmission

Orthohepadnaviruses

Within humans

- Horizontal

- Direct transmission

- person-to-person

- From healthcare workers

- Sexual contact

- Parenteral exposure

- Indirectly

- Unsafe medical practices

- Transfusions and haemodialysis

- Direct transmission

- Vertical

- Perinatal period

- Mother-to-offspring

Until 2000, there were more than 5.2 million cases of acute hepatitis B infection, and chronically infects approximately 5% of the human population.[2] HBV is the most common one among those hepatitis viruses. It can cause chronic infection of liver in humans, which has become a global public health problem, since chronic hepatitis can cause cirrhosis or death from liver failure within certain times. And it is the major cause of HCC, contributing about 60-80% of the HCC cases around the world.

HBV is transmitted by parenteral contact with body fluids, such as blood and lymph; perinatal exposure of infants to carrier mothers. It is thought that mother-to-child perinatal transmission and the establishment of a lifelong highly infectious carrier state are responsible for the observed high rates of endemicity in high-prevalence regions such as South and East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In some cases breast milk of HBsAg positive mothers has been found to be positive for the virus, but there have not been any reports of HBV transmission through breast-feeding, even before the availability of hepatitis B vaccine for infants.

- Horizontal transmission: through directly contacts with infected body fluids, like blood and lymph, in ways like sexual contacts, from health-care workers, or parenteral exposure; indirectly through transfusions and haemodialysis, and contaminated medical practices.

- Vertical transmission: through perinatal periods, mother to child.

Cross-species transmission

Cross-species transmission has not been proven yet, but if this occurs, the chance to eradicate HBV infection by immunization will be diminished due to the difficulty in controlling of natural virus reservoir. And increasing human encroachment on rainforest habitat and fragmentation of declining populations increases the interactions and consequently the risks of disease transmission between wild primates and human populations. Transmission of mammalian hepadnavirus strains between cross-species primate hosts has been found in many cases, recombination of hepadnavirus strains from cross-species primate hosts, further demonstrates that primate associated HBV strains can indeed share hosts in nature, and cross-species transmission of primate-associated HBV strains provides the probability of interspecies recombination.[5]

Within non-human mammals

- Gibbon HBV: Between gibbon and chimpanzee: the inoculation of GiHBV to a chimpanzee resulted in the acute hepatitis infection, and the virus isolated from the infected chimpanzee was GiHBV too.[6]

- Woolly monkey HBV: Since black-handed spider monkey belongs to the same family and subfamily as the woolly monkey, it was chosen as a suitable small primate model to study WMHBV. The results showed that the black-handed spider monkey was susceptible to WMHBV, but developed only a subclinical infection. The susceptibility of chimpanzees to WMBHV was only limited.[7]

- WHV: has only been detected in eastern woodchucks (Marmota monax), and does not infect related alpine marmosets. It infects woodchucks, but not other rodents like ground squirrels. But HDV with a WHV envelope (wHDV) has been shown to infect chimpanzees, and primary human hepatocytes. Vice versa a human enveloped hHDC could enter and (transiently) infect woodchuck hepatocytes in vivo without the need for a helper virus, but an infection of woodchucks or primary woodchuck hepatocytes with HBV has not been described.[8]

- GSHV: infects woodchucks and ground squirrels, specifically some species of squirrel (Spermophilus beecheyi and Spermophilus richardsonii) and the phylogenetically closely related chipmunks. GSHV runs a milder course when inoculated into woodchucks with the delayed onset of HCC.[9]

Between humans and non-human mammals

Since the similarity between human and apes, and common ancestors human and apes shared long time ago, there are possibilities to happen transmission of HBVs among them. The prevalence of HBV infection in the natural primate habitat is unknown. Most data resulted from the studies performed on samples obtained from captive animals, wild-born or captive-born. Human HBV infects only humans and closely related primates, such as chimpanzee, chacma baboon, and to some extent, tree shrew, but does not infect woolly monkeys. HBV isolates have been shown to infect gibbon apes and chimpanzees, but not convincing evidence of an infection of macaques or other members of the Cercopithecidea family. Macaca sylvanus is able to replicate HBV in vivo replication in primary macaque hepatocytes. However, susceptibility of these animals has not been shown.

- Gibbons: studies show that the vertical transmission is essential in the transmission of HBV in the non-human primates. But, there is also a possibility of horizontal transmission confirmed by HBV DNA detection in gibbon saliva. If the gibbons were housed in the same habitat, they would likely transmit HBV to the other gibbons through sexual contact or horizontal transmission of family members.[10]

- Chimpanzees: viral hepatitis had been known to occur in captive chimpanzees even prior to the discovery of HBV. Many studies used the chimpanzee models which have been limited now, showed that shortly after the first cloning of the HBV genome, the cloned DNA was infectious in chimpanzees, mostly developed hepatic pathology similar to the acute HBV infection in human, but they did not develop a chronic liver disease.[11]

- Tupaias: they are susceptible to the human HBV. However, the experimental infection is not highly efficient and causes only a mild, transient infection with low viral titers. Primary hepatocytes isolated from the liver of Tupaias are well susceptible to HBV infection.[1]

- Mice: Several researchers developed transgenic mice in order to study the expression of coding regions for the surface antigens, products of preS, S, and X gene of HBVs. The transgenic mice were not susceptible to HBV, but mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) can develop chronic liver disease. In addition, they permitted HBV to replicate in human hepatocytes that were able to proliferate in these mice.[7]

In general, these results imply that nonhuman primate HBV variants may be transmittable to humans. At least they infect representatives of the families Pongidae and Hylobatidae. However, at present it remains to be elucidated if nonhuman primate HBV variants are transmittable to humans and whether they cause disease in humans. And till now, no report of HBV transmission from captive animals to humans currently exists.[3] However the potential for zoonotic disease transmission exists where blood or body fluid exposure is common. Such scenarios could include chronically infected animals kept as family pets, close contact with caretakers, in situations in which chimpanzees are slaughtered and used as bushmeat.

Avihepadnaviruses

Within birds

Many cases about avihepadnaviruses transmission between or within species have been studied.

- DHBV: infects only certain duck and goose species, but does not even infect Muscovy ducks or chickens, or infects them inefficiently.[12]

- Heron HBV: does not infect ducks and only infects primary duck hepatocytes very inefficiently. Studies on different heron species which are geographically isolated populations suggest that lateral transmission, virus adaptation and environmental factors all play a role in HHBV spreading and evolution, but it is not clear whether HHBV infection occurs at all in free-living herons, due to the possibility of cross-species virus transmission.[13]

- Crane HBV: cranes are phylogenetically very distant from ducks and are more closely to herons and stocks, but CHBV infects primary duck hepatocytes with efficiency similar to DHBV.

Between humans and birds

There is no evidence for transmission of avian hepadnavirus between avian and human, but recombination of avihepadnavirus strains between cross-species avian hosts can offer potentials for the transmission between human and bird, considering that many birds are one of the main sources of food for human.[5]

Factors affecting transmission

- Species specificity

The special replication strategy gives this genus a special character, but also the high replication capacity and high error rate of the viral reverse transcriptase, thus HBVs from this genus have the ability to adapt to the host's environment, and varies from different hepadnaviruses, thus exhibiting species specificities.

- Proteins

Pre S1 regions of the L protein, exhibiting different host specificity, if proteolytically being removed from HBV particles results in a loss of infectivity. The S protein therefore is needed, but not sufficient for HBV entry. In contrast to the M protein, the L protein is essential for the viral infectivity. These special proteins plays different role in different viruses, thus determining the different host ranges, if this were strictly true, we would expect that divergence in pre-S would affect cross-species infection,[14] which then can contribute the different transmission of different hepadnaviruses.

- Replacing the special region of the envelope protein of one hepadnavirus with another hepadnavirus's.[8]

- HHBV by DHBV:infect ducks and derived primary hepatocytes

- WMHBV by HBV:infect human hepatocytes

- Subviral sphere particles: They are assumed to have the ability of absorbing virus-neutralizing antibodies to facilitate the virus spread and maintenance in the host.

Potentials

- Co-infection

A lot of studies have well characterized the horizontal transmission of HBV through parenteral routes and co-infections with different genotypes of HBV have also been reported, including genotypes A and D, genotypes A and G, and genotypes B and C. In Asia, genotypes B and C account for almost all HBV infections. Infection with genotype C may induce more severe liver diseases than infection with genotype B. Recombination between genotypes B and C can occur as the result of co-infection of the two genotypes and recombinant strains may possess an enhanced disease-inducing capacity compared with genotype B. It has also been reported that the predominance of recombinant strains between genotypes B and C might be associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in young carriers in Taiwan.[12]

- Recombination

Though the hepadnaviruses have a very limited host range, with the potential cross-species transmission of hepadnavirus among primates and some families of birds, combined with recombinants, it might change the hepadnavirus host specificity. Interspecies recombination between hepadnaviruses from cross-species hosts would provide a large variation of virus genome, which will change the pathogenicity and transmissibility, and enlarge the host range; the first evidence of potential recombination between chimpanzee HBV and human HBV genome was documented, recombination between human and non-human primate HBV strains, between GiHBV strains from different genera of gibbons, and between birds HBV strains from different avian sub-families were confirmed. All those experiments provided data allowing us to better understand the background, virus hosts, and zoonotic transmission of the non-human primate HBVs.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seeger, Christoph; Zoulim, Fabien; Mason, William S (2006). "Hepadnaviruses". In Knipe, David M; Howley, Peter M; Griffin, Diane E; et al. (eds.). Fields Virology (5th ed.). ISBN 978-0-7817-6060-7.

- 1 2 Visualization and Characterization Of hbv-Receptor Interactions, by Anja. Meier, Faculty of Life Sciences (2010),volume 92, pages 3-6.

- 1 2 3 Schaefer, S (2007). "Hepatitis B virus taxonomy and hepatitis B virus genotypes". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (1): 14–21. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.14. PMC 4065870. PMID 17206751.

- ↑ Tatematsu, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Kurbanov, F.; Sugauchi, F.; Mano, S.; Maeshiro, T.; Nakayoshi, T.; Wakuta, M.; et al. (2009). "A Genetic Variant of Hepatitis B Virus Divergent from Known Human and Ape Genotypes Isolated from a Japanese Patient and Provisionally Assigned to New Genotype J". Journal of Virology. 83 (20): 10538–47. doi:10.1128/JVI.00462-09. PMC 2753143. PMID 19640977.

- ↑ Lanford, R. E.; Chavez, D.; Rico-Hesse, R.; Mootnick, A. (2000). "Hepadnavirus Infection in Captive Gibbons". Journal of Virology. 74 (6): 2955–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.6.2955-2959.2000. PMC 111792. PMID 10684318.

- 1 2 Sa-Nguanmoo, P.; Rianthavorn, P.; Amornsawadwattana, S.; Poovorawan, Y. (2009). "Hepatitis B virus infection in non-human primates". Acta Virologica. 53 (2): 73–82. doi:10.4149/av_2009_02_73. PMID 19537907.

- 1 2 Grethe, S.; Heckel, J.-O.; Rietschel, W.; Hufert, F. T. (2000). "Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus Variants in Nonhuman Primates". Journal of Virology. 74 (11): 5377–81. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.11.5377-5381.2000. PMC 110896. PMID 10799618.

- ↑ Trueba, Daniel; Phelan, Michael; Nelson, John; Beck, Fred; Pecha, Brian S.; Brown, R. James; Varmus, Harold E.; Ganem, Don (1985). "Transmission of ground squirrel hepatitis virus to homologous and heterologous hosts". Hepatology. 5 (3): 435–9. doi:10.1002/hep.1840050316. PMID 3997073. S2CID 31754671.

- ↑ Noppornpanth, S.; Haagmans, BL; Bhattarakosol, P; Ratanakorn, P; Niesters, HG; Osterhaus, AD; Poovorawan, Y (2003). "Molecular epidemiology of gibbon hepatitis B virus transmission". Journal of General Virology. 84 (Pt 1): 147–55. doi:10.1099/vir.0.18531-0. hdl:1765/8468. PMID 12533711.

- ↑ Hu, X.; Margolis, H. S.; Purcell, R. H.; Ebert, J.; Robertson, B. H. (2000). "Identification of hepatitis B virus indigenous to chimpanzees". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (4): 1661–4. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1661H. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.4.1661. PMC 26492. PMID 10677515.

- 1 2 Liu, Wei; Zhai, Jianwei; Liu, Jing; Xie, Youhua (2010). "Identification of natural recombination in duck hepatitis B virus". Virus Research. 149 (2): 245–51. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2010.02.002. PMID 20144903.

- ↑ Lin, L.; Prassolov, A; Funk, A; Quinn, L; Hohenberg, H; Frölich, K; Newbold, J; Ludwig, A; et al. (2005). "Evidence from nature: interspecies spread of heron hepatitis B viruses". Journal of General Virology. 86 (Pt 5): 1335–42. doi:10.1099/vir.0.80789-0. PMID 15831944.

- ↑ Guo, H.; Mason, W. S.; Aldrich, C. E.; Saputelli, J. R.; Miller, D. S.; Jilbert, A. R.; Newbold, J. E. (2005). "Identification and Characterization of Avihepadnaviruses Isolated from Exotic Anseriformes Maintained in Captivity". Journal of Virology. 79 (5): 2729–42. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.5.2729-2742.2005. PMC 548436. PMID 15708992.