Trøndelag County

Trøndelag fylke Trööndelagen fylhke | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trondhjems amt (historic name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

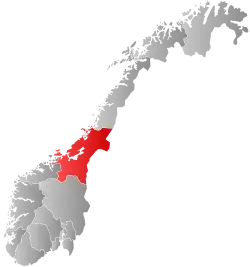

Trøndelag within Norway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates: 63°25′37″N 10°23′35″E / 63.42694°N 10.39306°E | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | Norway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| County | Trøndelag | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| District | Central Norway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Established | 1 Jan 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Preceded by | Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag counties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Administrative centre | Steinkjer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Body | Trøndelag County Municipality | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Governor (2018) | Frank Jenssen (H) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • County mayor (2018) | Tore O. Sandvik (Ap) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 42,202 km2 (16,294 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Land | 39,494 km2 (15,249 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Water | 2,708 km2 (1,046 sq mi) 6.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Rank | #3 in Norway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population (2021) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 471,124 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Rank | #5 in Norway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Density | 11.9/km2 (31/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Change (10 years) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym | Trønder[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official language | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Norwegian form | Neutral | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | NO-50[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Trøndelag (Urban East Norwegian: [ˈtrœ̂ndəˌlɑːɡ];[7][8] or Trööndelage (Southern Sami) is a county in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County (Norwegian: Trondhjems Amt); in 1804 the county was split into Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag by the King of Denmark-Norway, and the counties were reunited in 2018 after a vote of the two counties in 2016.[9][10]

The largest city in Trøndelag is the city of Trondheim. The administrative centre is Steinkjer, while Trondheim functions as the office of the county mayor.[11] Both cities serve the office of the county governor; however, Steinkjer houses the main functions.[12]

Trøndelag county and the neighbouring Møre og Romsdal county together form what is known as Central Norway. A person from Trøndelag is called a trønder. The dialect spoken in the area, trøndersk, is characterized by dropping out most vowel endings; see apocope.

Trøndelag is one of the most fertile regions of Norway, with large agricultural output. The majority of the production ends up in the Norwegian cooperative system for meat and milk, but farm produce is a steadily growing business.

Name

The Old Norse form of the name was Þrǿndalǫg. The first element is the genitive plural of þrǿndr which means "person from Trøndelag", while the second is lǫg (plural of lag which means "law; district/people with a common law" (compare Danelaw, Gulaþingslǫg and Njarðarlǫg). A parallel name for the same district was Þróndheimr which means "the homeland (heim) of the þrǿndr".[13] Þróndheimr may be older since the first element has a stem form without umlaut.

The county and national governments have also approved a Sami language name for the county. The spelling of the Sami language name changes depending on how it is used. It is called Trööndelage when it is spelled alone, but it is Trööndelagen fylhke when using the Sami language equivalent to "Trøndelag county".[14] There are also other alternatives for the various Sami dialects that are not exactly the same as the officially adopted name.

History

People have lived in this region for thousands of years. In the early iron-age Trøndelag was divided into several petty kingdoms called fylki. The different fylki had a common law, and an early parliament or thing. It was called Frostating and was held at the Frosta-peninsula. By some, this is regarded as the first real democracy.

In the time after Håkon Grjotgardsson (838-900), Trøndelag was ruled by the Jarl of Lade. Lade is located in the eastern part of Trondheim, bordering the Trondheimsfjord. The powerful Jarls of Lade continued to play a very significant political role in Norway up to 1030.

Jarls of Lade (Ladejarl) were:

- Håkon Grjotgardsson, the first jarl of Lade.

- Sigurd Håkonsson, son of Håkon. Killed by Harald Greyhide.

- Håkon Sigurdsson, son of Sigurd. Conspired with Harald Bluetooth against Harald Greyhide, and subsequently became vassal of Harald Bluetooth, and in reality independent ruler of Norway. After the arrival of Olaf Trygvason, Håkon quickly lost all support and was killed by his own slave, Tormod Kark, in 995.

- Eirik Håkonsson, son of Håkon. Together with his brother, Svein, governor of Norway under Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark from 1000 to 1012.

- Håkon Eiriksson, son of Eirik. Governor of Norway under Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark from 1012 to 1015.

Trøndelag (together with parts of Møre og Romsdal) was briefly ceded in 1658 to Sweden in the Treaty of Roskilde and was ruled by king Charles X until it was returned to Denmark-Norway after the Treaty of Copenhagen in 1660. During that time, the Swedes conscripted 2,000 men in Trøndelag, forcing young boys down to 15 years of age to join the Swedish armies fighting against Poland and Brandenburg. Charles X feared the Trønders would rise against their Swedish occupiers, and thought it wise to keep a large part of the men away. Only about one-third of the men ever returned to their homes; some of them were forced to settle in the then Swedish Duchy of Estonia, as the Swedes thought it would be easier to rule the Trønders there, utilising the ancient maxim of divide and rule.[15]

In the fall of 1718, during the Great Northern War, General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt was ordered by king Charles XII of Sweden to lead a Swedish army of 10,000 men into Trøndelag to take Trondheim. Because of his poor supply lines back to Sweden, Armfeldt's army had to live off the land, causing great suffering to the people of the region. Armfeldt's campaign failed: the defenders of Trondheim succeeded in repelling his siege. After Charles XII was killed in the siege of Fredriksten in Norway's southeast, Armfeldt was ordered back into Sweden. During the ensuing retreat, his 6,000 surviving threadbare and starving Caroleans were caught in a fierce blizzard. Thousands of Caroleans froze to death in the Norwegian mountains, and hundreds more were crippled for life.[16]

Government

The county is governed by the Trøndelag County Municipality. The town of Steinkjer is the seat of the county governor and county administration. However, both the county governor and Trøndelag County Municipality also have offices in Trondheim.

The county oversees the 41 upper secondary schools, including nine private schools. Six of the schools have more than 1000 students: four in Trondheim plus the Steinkjer Upper Secondary School and the Ole Vig Upper Secondary School in Stjørdalshalsen. The county has ten Folk high schools, with an eleventh folk high school being possibly being opened in Røros, with a possible start in 2019.[17]

Districts

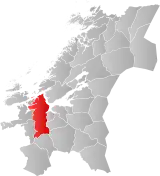

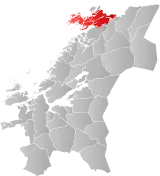

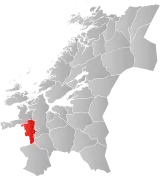

The county is often sub-divided into several geographical regions:

- Namdal, the greater Namsen river valley

- Fosen, the Fosen peninsula and surrounding areas

- Innherred, the areas surrounding the inner Trondheimsfjorden

- Stjørdalen, the Stjørdalen valley

- Trondheim Region, the areas surrounding the large city of Trondheim

- Gauldalen, the Gaula river valley

- Orkdalen, the Orkla river valley

Towns and cities

There are ten towns/cities in Trøndelag, plus the "mining town" of Røros.

- Trondheim (in Trondheim municipality)

- Steinkjer (in Steinkjer municipality)

- Stjørdalshalsen (in Stjørdal municipality)

- Levanger (in Levanger municipality)

- Namsos (in Namsos municipality)

- Rørvik (in Nærøysund municipality)

- Verdalsøra (in Verdal municipality)

- Orkanger (in Orkdal municipality)

- Brekstad (in Ørland municipality)

- Kolvereid (in Nærøy municipality)

- Bergstaden Røros (in Røros municipality)

Geography

Along the coast in the southwest are the largest islands in Norway south of the Arctic Circle, including Hitra and Frøya. The broad and long Trondheimsfjord is a main feature, and the lowland surrounding the fjord are among the most important agricultural areas in Norway. In the far south is the mountain ranges Dovrefjell and Trollheimen, and in the southeast is highlands and mountain plateaus, and this is where Røros is situated. The highest mountain is the 1,985-metre (6,512 ft) tall Storskrymten, which is located in the county border between Møre og Romsdal, Innlandet and Trøndelag. North of the Trondheimsfjord is the large Fosen peninsula, where Ørland is at its southwestern tip. Several valleys runs north or west to meet the fjord, with a river at its centre, such as Meldal, Gauldal, Stjørdal, Verdal. Further north is the long Namdalen with the largest river, Namsen, and Namsos is situated where the river meets the Namsen fjord. The rivers are among the best salmon rivers in Europe, especially Namsen, Gaula, and Orkla. On the northwestern part of the region is the Vikna archipelago with almost 6,000 islands and islets.

There are many national parks in the region, including Dovrefjell–Sunndalsfjella National Park, Forollhogna National Park, Skarvan and Roltdalen National Park, Femundsmarka National Park and Børgefjell National Park.

Climate

Trøndelag is one of the regions in Norway with the largest climatic variation - from the oceanic climate with mild and wetter winters along the coast to the very cold winters in the southeast inland highlands, where Røros is the only place in southern and central Norway to have recorded −50 °C (−58 °F). The first overnight freeze (temperature below −0 °C (32 °F) in autumn on average is August 24th in Røros, October 9th at Trondheim Airport Værnes, and as late as November 20th at Sula in Frøya.[18] Most of the lowland areas near the fjords have a humid continental climate (or oceanic if -3C is used as winter threshold), while the most oceanic areas along the coast have a temperate oceanic climate with all monthly means above 0 °C (32 °F). The inland valleys, hills, and highlands below the treeline have a boreal climate with cold winters and shorter summers, but still with potential for warm summer temperatures. Above the treeline is alpine tundra.

| Climate data for Sula, Frøya 1991-2020 (5 m, extremes 1975-2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13 (55) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.9 (44.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8 (46) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13 (55) |

13.7 (56.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6 (43) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.3 (9.9) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5 (41) |

7.1 (44.8) |

2 (36) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−7 (19) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 92 (3.6) |

75 (3.0) |

80 (3.1) |

55 (2.2) |

46 (1.8) |

53 (2.1) |

57 (2.2) |

74 (2.9) |

104 (4.1) |

88 (3.5) |

108 (4.3) |

113 (4.4) |

945 (37.2) |

| Source 1: Norwegian Meteorological Institute[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA-WMO averages 91-2020 Norway [20] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Trondheim Airport Værnes 1991–2020 (12 m, extremes 1946–2020, sunhrs 2016–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.3 (88.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1 (30) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1 (34) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11 (52) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.1 (24.6) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.6 (−14.1) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64.6 (2.54) |

63.9 (2.52) |

61.3 (2.41) |

42.1 (1.66) |

52.7 (2.07) |

76.1 (3.00) |

74.4 (2.93) |

82.8 (3.26) |

88.9 (3.50) |

77 (3.0) |

64.4 (2.54) |

75 (3.0) |

823.2 (32.43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 149 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 34 | 71 | 124 | 205 | 236 | 234 | 229 | 167 | 130 | 116 | 46 | 16 | 1,608 |

| Source 1: Seklima [21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOOA-WMO averages 91-2020 Norway [22] | |||||||||||||

Trøndelag

There are 38 municipalities in Trøndelag.[23]

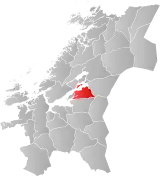

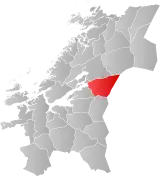

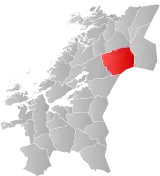

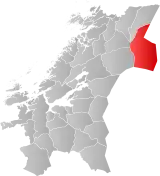

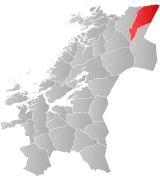

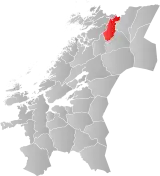

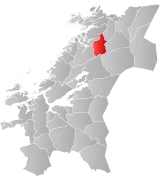

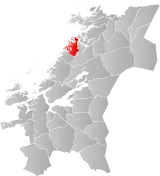

| Municipal Number | Name | Adm. Centre | Location in the county | Established | Old Municipal No. (before 2020) | Former County |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5001 | Trondheim |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 5001 Trondheim 5030 Klæbu | Trøndelag | |

| 5006 | Steinkjer |  | 23 Jan 1858 | 5006 Steinkjer 5039 Verran | ||

| 5007 | Namsos | 1 Jan 1846 | 5005 Namsos 5040 Namdalseid 5048 Fosnes | |||

| 5014 | Sistranda |  | 1 Jan 1964 | 1620 Frøya | Sør-Trøndelag | |

| 5020 | Steinsdalen |  | 1 June 1892 | 1633 Osen | ||

| 5021 | Oppdal |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1634 Oppdal | ||

| 5022 | Berkåk |  | 1 Jan 1839 | 1635 Rennebu | ||

| 5025 | Røros |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1640 Røros | ||

| 5026 | Renbygda |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1644 Holtålen | ||

| 5027 | Støren |  | 1 Jan 1964 | 1648 Midtre Gauldal | ||

| 5028 | Melhus |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1653 Melhus | ||

| 5029 | Børsa |  | 1 Jan 1890 | 1657 Skaun | ||

| 5031 | Hommelvik |  | 1 Jan 1891 | 1663 Malvik | ||

| 5032 | Mebonden |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1664 Selbu | ||

| 5033 | Ås |  | 1 Jan 1901 | 1665 Tydal | ||

| 5034 | Midtbygda |  | 1 Jan 1874 | 1711 Meråker | Nord-Trøndelag | |

| 5035 | Stjørdalshalsen |  | 1 Jan 1902 | 1714 Stjørdal | ||

| 5036 | Frosta |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1717 Frosta | ||

| 5037 | Levanger |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1719 Levanger | ||

| 5038 | Verdalsøra |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1721 Verdal | ||

| 5041 | Snåsa |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1736 Snåsa | ||

| 5042 | Sandvika |  | 1 Jan 1964 | 1738 Lierne | ||

| 5043 | Røyrvik |  | 1 July 1923 | 1739 Røyrvik | ||

| 5044 | Namsskogan |  | 1 July 1923 | 1740 Namsskogan | ||

| 5045 | Medjå |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1742 Grong | ||

| 5046 | Høylandet |  | 1 Jan 1901 | 1743 Høylandet | ||

| 5047 | Ranemsletta |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1744 Overhalla | ||

| 5049 | Lauvsnes |  | 1 Jan 1871 | 1749 Flatanger | ||

| 5052 | Leknes |  | 1 Oct 1860 | 1755 Leka | ||

| 5053 | Straumen |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 1756 Inderøy Mosvik | ||

| 5054 | Årnset |  | 1 Jan 2018 | 1624 Rissa | Sør-Trøndelag | |

| 1718 Leksvik | Nord-Trøndelag | |||||

| 5055 | Kyrksæterøra |  | 1 Jan 2020 | 1571 Halsa | Møre og Romsdal | |

| 5011 Hemne 5012 Snillfjord (part) | Trøndelag | |||||

| 5056 | Fillan |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 5013 Hitra 5012 Snillfjord (part) | ||

| 5057 | Botngård |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 5015 Ørland 5017 Bjugn | ||

| 5058 | Årnes |  | 1 Jan 1838 | 5018 Åfjord 5019 Roan | ||

| 5059 | Orkanger |  | 1 Jan 2020 | 5012 Snillfjord (part) 5016 Agdenes 5023 Meldal 5024 Orkdal | ||

| 5060 | Kolvereid and Rørvik |  | 1 Jan 2020 | 5050 Vikna 5051 Nærøy | ||

| 5061 | Rindal |  | 1 Jan 1858 | 1567 Rindal | Møre og Romsdal |

Other municipalities

Kristiansund in Møre og Romsdal held a referendum on 17 January 2022 on whether to move from Møre og Romsdal to Trøndelag, which was rejected; 36.77% voted to move, while 63.23% voted to stay.[24] Similar referendums were hosted and rejected the preceding autumn in Aure on 13 September 2021 (45% to move, 51% to stay),[25] and in Smøla on 26 September 2021 (27.24% to move, 70.23% to stay).[26]

Bindal in Nordland was originally decreed by Stortinget on 8 June 2017 to become part of Nærøysund (and thus become part of Trøndelag),[27] but the decision was reversed after another hearing on 21 November 2017,[28] well in advance of Nærøysund becoming a municipality on 1 January 2020.

Culture

Arts

The region's official theatre is the Trøndelag Teater in Trondheim.[29] At Stiklestad in Verdal, the historical play called The Saint Olav Drama has been played each year since 1954. It depicts the last days of Saint Olaf.

Jazz on a very high level is frequently heard in Trondheim, due to the high-level jazz education in Trondheim at Institutt for musikk (NTNU). Trondheim is also the national centre of rock music; the popular music museum Rockheim opened there in 2010. Trøndelag is known for its local variety of rock music, often performed in local dialect, called "trønderrock".

Several institutions are nationally funded, including the internationally acclaimed Trondheim Symphony Orchestra, Trondheim Soloists, Olavsfestdagene and Trondheim Chamber Music Festival.

Food and drink

The region is popularly known for its moonshine homebrew, called heimbrent or heimert. Although officially prohibited, the art of producing as pure homemade spirits as possible still has a strong following in parts of Trøndelag. Traditionally the spirit is served mixed with coffee to create a drink called karsk. The strength of the coffee varies, often on a regional basis. The mixing proportions also depend on the strength of the spirit with more coffee being used for spirit with higher alcohol content. In southern regions, people tend to use strong filter coffee, while in the north they typically serve karsk with as weak coffee as possible.

The "official dish" of the region is sodd which is made from diced sheep or beef meat and meatballs in boiled stock. The Norwegian Grey Troender sheep is an endangered breed of domesticated sheep that originated from Trøndelag in the late 19th century. There are currently approximately 50 individual animals remaining and efforts are being made to revive the breed.

Agriculture

Trøndelag is covered with fertile lands, especially the lowlands surrounding the Korsfjord, Trondheimsfjord, Borgenfjord, and Beitstadfjord. Trøndelag is the third largest county in Norway by agricultural land with its 1789sqkm,[30] and has the second highest meat-output with a total of almost 75 000 tonnes in 2022.[31] The county also houses the most milking-cows, and thereby has the highest milk output,[32] with Steinkjer Kommune producing the most.[33]

In 2018 Trøndelag was the largest provider of beef, chicken, milk and eggs, outputting 21.1% of all milk production, and 18.9% of all beef, 28.7% of all chicken, 23.5% of all eggs, 13.2% of cereals and 23.2% of all hay produced in Norway. Trøndelag is very much a rural county, housing merely 8.7% of Norway's population.[34]

Domestic Breeds

Trøndelag is the origin of multiple animal breeds, the best known being Grey Troender sheep and Sided Troender cattle (STN).

Sided Troender cattle, as the name implies, is a white cow with coloured sides. It is based on "Rørosfe" from the Røros area, but later merged with the less standardized Nordland cattle. Together they are viewed as one breed with roots in both Trøndelag and Nordland, and has been since the 1920s. The breed standards are based on the original Trønder standards rather than the looser Nordland standards, with some cows being red, prioritizing black sides on hornless white cows. These are the traits most reminiscing of the old "Rørosfe".[35]

Red Troender cattle is a now extinct breed based on the Scottish Ayrshire cattle. This domestic breed of horned red cows was mixed into extinction in the 1960s, and is now succeeded by Norwegian Red Cattle (NRF).[36]

Tautra sheep (Tautersau) was a breed of sheep from the island Tautra, which was and still is heavily populated by monks, who have held sheep since the 11th century.[37] It is thought that the breed is a fork of Spanish Merino sheep brought to Norway by monks during the 1500s. This theory has little written evidence to support it, which may be explained by Spains monopoly on Merino sheep until the 1800s, and export of the breed was punishable by death. Another theory is that the fine wool-features come from Moroccan sheep that were left on some islands outside Frøya. The presence of Moroccan sheep on Tarva was documented in 1757, and they are thought to have been brought inland. What is known for certain is that Hertfordshire Ryelander rams were imported in the late 1700s to mate with the local Tautra sheep. The Norwegian government held a breeding station on Edøy, that was laid to waste by invading forces during WWII. Despite a couple of desentralized breeding stations the population was too low, and to prevent inbreeding it was mixed, amongst others with Old Norwegian Sheep, to improve the quality of other breeds.

Grey Troender sheep is an endangered breed counting only 50 specimens in the year 2000. The crossbreeding to create the Grey Troender started in the late 1800s with heavy influence from Old Norwegian Sheep and Tautra Sheep.[38] To protect this breed the government subsidises breeders. By 2011 the population had grown to 1200, whereof 500 are fertile ewes, distributed among 35 herds. The Committee on Farm Animal Genetic Resources has collected and frozen 3500 sperm-samples for future breeding.

Troender Rabbit (Trønderkanin) Is the only domestic Norwegian breed of rabbit. The breed was very popular during WWII as it grew fast and provided a fair amount of meat. Interest in the breed tapered off in the 1970s, and the population was as low as 40 specimens in the 1990s. The population in 2017 was around 80 specimens.f[39]

See also

References

- ↑ "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- ↑ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ↑ Bolstad, Erik; Thorsnæs, Geir, eds. (2023-01-26). "Kommunenummer". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget.

- ↑ Statistisk sentralbyrå (2020). "Table: 06913: Population 1 January and population changes during the calendar year (M)" (in Norwegian).

- ↑ "Statistics Norway - Church of Norway". Archived from the original on July 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Statistics Norway - Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance. County. 2006-2010". Archived from the original on 2011-11-02. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- ↑ Berulfsen, Bjarne (1969). Norsk Uttaleordbok (in Norwegian). Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co (W Nygaard). p. 336.

- ↑ Vanvik, Arne (1985). Norsk Uttaleordbok: A Norwegian pronouncing dictionary (in Norwegian and English). Oslo: Fonetisk institutt, Universitetet i Oslo. p. 311. ISBN 978-8299058414.

- ↑ Hofstad, Sigrun (2016-04-27). "Her bankes det for et samlet Trøndelag". NRK (in Norwegian).

- ↑ "Trøndelag fylke: English". Trøndelag fylke. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- ↑ "Fakta om Trøndelag". www.trondelagfylke.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ↑ "Om oss". Trøndelag (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ↑ Sandnes, Jørn; Stemshaug, Ola (1980). Norsk stadnamnleksikon. pp. 322–323.

- ↑ "Stadnamn og rettskriving" (in Norwegian). Kartverket. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ↑ Gjerset, Knut (1915). History of the Norwegian People, Volumes II. The MacMillan Company. pp. 318–320.

- ↑ "Historien" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ↑ Olsen Haugen, Morten, ed. (2018-03-10). "Trøndelag". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- ↑ "Første frostnatt". 25 September 2013.

- ↑ "Norwegian Meteorological Institute".

- ↑ "NOAA WMO normals Norway 1991-2020".

- ↑ seklima.met.no

- ↑ "NOAA WMO normals Norway 1991-2020".

- ↑ List of Norwegian municipality numbers

- ↑ "Folk i Kristiansund vil bli i Møre og Romsdal" (in Norwegian Nynorsk). NRK. 18 January 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ "Aure har stemt over om de vil bli trøndere" (in Norwegian Bokmål). Adressa. 14 September 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ "Smøla har stemt: Vil bli værende i Møre og Romsdal" (in Norwegian Bokmål). Aftenposten. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ "Bindal blir trøndersk" (in Norwegian Bokmål). NRK. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ "Nordlandskommune forsvinner likevel ikke ut av fylket" (in Norwegian Bokmål). Avisa Nordland. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ Haugan, Trond E (2008). Byens magiske rom: Historien om Trondheim kino. Tapir Akademisk Forlag. ISBN 9788251922425.)

- ↑ "09594: Arealbruk og arealressurser, etter arealklasser (Km²) (K) (B) 2011 - 2022. Statistikkbanken".

- ↑ "Fakta om jordbruk - Statistisk sentralbyrå".

- ↑ "Hvor i Norge er det flest melkegårder?".

- ↑ "Store endringer i melkeproduksjonen i Trøndelag".

- ↑ "Faktafredag - Jordbruksproduksjon i Trøndelag".

- ↑ "Blacksided Trondheim and Norland Cattle". Breeds of cattle. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ↑ "Norwegian Red Cattle". Breeds of cattle. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ↑ "About Tautersheep Sheep". Livestock of the world. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ↑ "Tautersau".

- ↑ "Trønderkanin". Nibio.

External links

Trøndelag travel guide from Wikivoyage

Trøndelag travel guide from Wikivoyage- Facts about Trøndelag from Mid-Norway European office

- Insular artifacts from Viking-Age burials from mid-Norway. A review of contact between Trøndelag and Britain and Ireland