The towers and palaces of the Roero in Asti are medieval buildings located in the San Martino-San Rocco district, in the area between Piazza San Giuseppe, Via Roero, Via Quintino Sella and Piazza San Martino. The Roero or "Rotari", one of the major families of the nobility[1] belonging to the houses of Asti, began to occupy the area at the beginning of the 13th century and, as a result of the increase in their profits obtained from trade and pawn money lending, they exponentially increased the colonization of the area. By the end of the 13th century, the Municipality of Asti, through the financing of the mercantile families was able to weave a fruitful network of alliances and trade agreements. The league that the municipality formed with Pavia, Genoa and the Marquisate of Saluzzo led to the defeat of the Angevin army[2] and enabled it to dominate over most of south-central Piedmont. The increase in Asti's political clout over Piedmont consequently led to a demographic and urban increase in the city of Asti throughout the 14th century. The seventeenth-century Laurus map shows how many strongholds and towers there still were in the city's built-up area and only leaves one to speculate what the actual urban layout was during the period of maximum fourteenth-century expansion.[3]

The density of the Roero dwellings present in the San Martino area also increased in proportion to the influence and expansion of the family. The Roero's power became such that in the 14th century they hosted Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg. At the end of his stay, Arrigo of Dantesque fame[4] as a sign of gratitude bestowed certain privileges that allowed the Contrada to be considered a free and inviolable territory with respect to the other city districts, assuming a connotation of extraterritoriality.[5] Even under Emperor Charles V, the family had special privileges. It was granted the right of asylum in one of their palaces in the contrada.[6]

The area for centuries was referred to as Contrada Roera, and the toponym remained until the late 19th century.

This is what the city of Asti looked like in the early 17th century. There were probably more towers in the medieval period, although many of those that were started were never completed due to the economic inability of the casane to afford the high construction costs.

(Copper engraving by Jacopo Lauro called "Asti, Nobilissima città del Piemonte 1639" from Guido Antonio Malabaila's book, "Compendio historiale della città d'Asti". Rome 1638).

The ward of San Martino

Contrada Roera,

in which by Imperial Privileges

no one can be captured,nor can the deceased be transported through it

— Map of Asti by Antonio Laurus

In the communal period, the shift from the commercial activity of goods to that of money led in Asti to a centralization of wealth around a limited group of families (the casane) that ended up characterizing and changing the urban fabric of the city as well.

These family groups organized themselves into subsystems consisting of fortified houses, connected by curtain walls and protected by towers, to constitute a larger urban whole, gravitating on the wards, within which the power of a specific family group and its allies held sway.[7]

The construction of towers also became the visual yardstick of the "social" rise of the household. They were certainly useful for defense, but they were mainly used to demonstrate economic prosperity and to self-celebrate one's political clout.[8]

The Roero settled in the San Martino district, one of the city's oldest neighborhoods. In fact, still in the statutes of 1379, the ward, referring to the ancient form urbis of the civitas, was considered as one of the two centers of aggregation of the ancient Roman city.[9] Located southwest of the city, the ward developed around some urban environments, military and socio-religious points of aggregation, present in that area: the gate of San Martino, the church of Sant'Ilario and the church of San Martino.

St. Martin's Gate, located at the outlet between Grassi Street and XX Settembre Street, in the southern part of the city, stood next to the present church of St. Roch.

The gate, by jurisdiction was divided into a number of contrade or vicinie with mainly aristocratic connotations:[10]

- a first vicinia comprising part of the contrada of San Sisto, which took its name from the church of the same name present as early as 886 on the ancient Roman decumanus at the level of the present-day Piazza Roma;[11]

- a contrada formed since the 13th century by part of the dwellings of the powerful Guelph Solaro family;

- the contrada Roera, comprising precisely the dwellings of the Roeros in the area of the church and the gate of San Martino.Passing through the San Martino gate, one reached the wall demarcation ditch, formed by the ancient canal, which was the town's first irrigation system and also an important river access for goods that could reach the Tanaro River from there. From there on, as far as the Borbore River, stretched the territory of the hamlet of San Martino, abounding in dyers' and tanners' stores, which, in contrast to the ward, had a strong popular connotation.

--- Nobles' enclosure and St. Martin's gatePiazza San GiuseppePiazza San MartinoLocation of the towers1 Church of San Giuseppe 2 Church of San Martino 3 Confraternity of San Michele a Palace of the Pelletta family of Cortazzone b Ruins of houses of the Roero family c Palace of the "equestrian games" d Palace of Calosso and of Cortanze e Tomatis Palace of Chiusavecchia f Palace and tower of Cortanze g The complex of Monteu h Palace of Settime and Mombarone i Palace and tower Musso-Isnardi

--- Nobles' enclosure and St. Martin's gatePiazza San GiuseppePiazza San MartinoLocation of the towers1 Church of San Giuseppe 2 Church of San Martino 3 Confraternity of San Michele a Palace of the Pelletta family of Cortazzone b Ruins of houses of the Roero family c Palace of the "equestrian games" d Palace of Calosso and of Cortanze e Tomatis Palace of Chiusavecchia f Palace and tower of Cortanze g The complex of Monteu h Palace of Settime and Mombarone i Palace and tower Musso-Isnardi

The contrata Rotariorum

The contrada Roera began to form in the 13th century. The first Roero families began to move from the area of Porta Vivarii di San Paolo into the district of Porta di San Martino, settling mainly along the axis of today's Via Roero.

The houses of the Roero family were arranged starting from the Porta di San Martino along the entire contrada, up to near the contrada maestra (today's Corso Alfieri) on the border with the properties of the Re family.

By the beginning of the 14th century the family's move to the San Martino area was practically complete.

The typology of the dwellings resumed the classic medieval house-fortress, consisting of the noble residence, the tower, the outhouse, the garden and the inner vegetable garden.

These buildings, independent of each other, were provided with a curtain wall when in the 13th century, with the intensification of struggles between the Guelph and Ghibelline parties,[12] there arose the need to fortify and protect properties.

During this period, Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg was hosted for more than a month in the house of Tommaso di Aicardo Roero,[13] a powerful Ghibelline leader. The emperor, grateful to the Roero for the hospitality he received, granted the Asti family certain privileges, among which were to inhibit the transit of funeral processions, forbid the construction of prisons in their district, grant pardons each year to three executioners, and to consider their palace an inviolable place of asylum for every person.[14]

This gave the area a status of "extraterritoriality," at that time the exclusive privilege of religious structures.[15]

Roero palaces in San Martino square

The Roero complex of Monteu

In 1299, a branch of the Roero family was invested by the bishop of Asti, Blessed Guido da Valperga,[16] with the places of Monteu, Santo Stefano Belbo and Castagnito.[17]

The palace located in Piazza San Martino at the corner of Via Roero was purchased by the family around the 14th century. It is the most representative palace of the contrada. Stefano Giuseppe Incisa in the 19th century considered it one of the best-preserved medieval palaces in the city.[18]

The original core of the complex consists of three buildings from the mid-13th century, which originally had their entrance on the alley that separated them from the church of San Martino, once with the facade facing the palaces to create a small square.[19]

Towards the end of the 13th century, the construction of the central tower, the true connecting point of the surrounding buildings, took place.

The entire block was raised with the construction of two floors each comprising three red-and-white biforas with "concave archivolt", typical of Asti architecture, creating a typical 14th-century palatium.

The 7.50-meter tower belongs to the "second period."

Once eight stories high, it presents bricks of lighter coloring at the corners, typical of 13th-century Asti architecture.

The ground floor still has a rib vault with cylindrical ogives that run toward the center, where there is a keystone in the form of a rose window.

Pictorial decorations embellish the tower, depicting the Roero coat of arms,[20] and the top features three bands of small arches ending in merlons.

In the Napoleonic period, the palace became the seat of the prefecture with the prefect's quarters. In 1804, the palace welcomed Pope Pius VII during his journey to France to crown Napoleon Bonaparte Emperor of the French.[21]

In 1814 the tower was lowered to its present height.

Roero Palace of Settime and Mombarone

On the western side of Piazza San Martino is the imposing 18th-century palace that continues throughout the block, following Via Malabayla to the junction of Via Asinari.

Gabiani places the core of the palace among the city's best 13th-century fortified houses.[14]

In reality, the eighteenth-century construction is the result of a number of amalgamations over the centuries.[22]

Falling plasterwork and deterioration that occurred in the last quarter of the 20th century revealed that there were as many as seven building bodies in the palace area.

In the 16th century, the block appeared to be divided into two large properties: the westernmost, toward Via Asinari, consisting of a building made up of bodies V, VI, VII, owned by the Mombarone lineage; the easternmost, toward Piazza San Martino, belonged to the Settime branch and consisted of the other buildings.

The buildings of the two estates, with the unification of the two families into a single lineage called "di Settime e Mombarone," were merged in the 18th century into a single building, not affecting the structural layout, but building externally a single Baroque facade facing San Martino Square.

In the 18th century, ownership passed to the nobleman Antonio Gaspare Guidobono Cavalchini, a court gentleman of the king of Sardinia, who by marrying Baroness Felicita Maria Roero assumed the title of Roero di San Severino.[23]

The palace eventually passed to the Pogliani family and in the early 20th century was used as the seat of the sub-prefecture and Public Security offices.

Roero palaces on Via Roero

Roero palace and tower of Monticello and Piea

This building is located on the western side of Via Roero after Piazza San Martino, on the corner with Via Q. Sella. Abbot Incisa writes that this building in ancient times belonged to the Roero family without, however, mentioning the family branch. In a 17th-century plan, preserved at the parish of San Martino, it is written that the building belonged to the Roero counts of Monticello and Piea.[24]

The 1700 Theatrum plan shows that the palace, now completely remodeled, was provided at the southeast corner with a wide tower similar to that of the Monteu family and a smaller tower adjacent to it. This was because the palace was in a strategic position to defend the district.[14]

The main floor of the palace still has ceilings decorated with 18th-century stucco work. The decorations were probably commissioned by the Cacherano della Rocca family who took over the property at that time.[22]

Roero Palace of Calosso and Cortanze

At the corner of Via Roero and Via Q. Sella, adjacent to the Roero di Cortanze palace and tower, there is a medieval building, named by Gabiani Palazzo Roero di Calosso e di Cortanze.

The palace was originally owned by the marshal and viceroy of Sardinia Tomaso Ercole, count of Calosso. On the occasion of the investiture of the marquis title of Cortanze, the palace took the name of Calosso-Cortanze.[25]

The palace, subject to continuous remodeling over the last few centuries, still retains part of the original palaxetum structure to such an extent that it may be assumed to have consisted of two orthogonal arms (one at Via Q. Sella and one at Via Roero), with a tower in the center of the corner similar to the one still present at the other Roero palace in Cortanze, at the corner with Via San Martino.[26] The palace passed into the ownership of Canon Francesco Oronzo Cagna and, in 1814, was given to the doctor Bruno.

Palace of Monticello and Piea with the hall of "equestrian games"

The building, located at street number 60 on Via Roero, consists of two orthogonal passageways joined to a third building by a seventeenth-century staircase. The first passageway, the one parallel to Via Roero, has a rectangular plan, consisting of three floors, the last two of which are the result of a 14th-century elevation.

The second floor has three biforas that were only recently rediscovered during a recent renovation. The biforas, built of terracotta and sandstone, have lunettes decorated with the three wheels of the Roero coat of arms. On the main floor, the ceiling is decorated with 18th-century friezes and stucco. This ceiling conceals a vault, practically inaccessible, consisting of a wooden ceiling and richly decorated with peacocks, fantastic animals, feats and floral trophies of 16th-century workmanship.

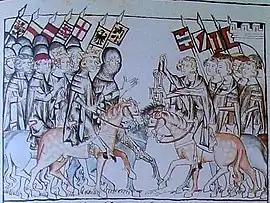

In the image: entrance of Henry VII into Asti, from the manuscript Bilderzyrclus von Kaiser Heinrichs Romfahrt, 1340.[27]

On November 10, 1310, Henry VII of Luxembourg arrived in Asti to subdue the city, which had been at the mercy of continuous civil wars for nearly fifty years. The emperor was accompanied by his brother-in-law Amadeus V of Savoy, his vicar in Piedmont.

During his stay, which lasted almost a month, he brought back the Ghibelline faction of De Castello, confirmed all privileges to the city, and renewed the Major Council: the Podestà and the Capitano del popolo were replaced by an imperial vicar.

The emperor left the city on December 12, 1310, for Milan. As a sign of submission, the people of Asti aggregated 100 militia and more than 1,000 infantrymen[28] to support the emperor engaged in some battles in Lombardy, but after a few years too many taxes and harassment by the imperial vicars (Amadeus V of Savoy and Philip of Acaja) made the city resentful of the sovereign. With the help of the Angevin seneschal Ugo del Balzo, they drove the Ghibelline faction of De Castello out of the city and on April 17, 1312, signed an act of dedication to King Robert of Anjou their lifelong enemy.[29]

The second passageway, orthogonal and leaning against the north side of the previous one, is of lesser importance and extent: it was probably built by the Roero family as part of the overall modernization and expansion of the building. Noteworthy are the monoforas with simple, two-colored archivolt. These two buildings are joined by a third one, also in an orthogonal position, via a seventeenth-century staircase.

The wooden ceiling of this third building is archaic in structure, with wooden rafters embedded in the wall without the support of corbels. It is fully decorated with fourteenth-century tournament scenes, emblems, mottos and heraldic feats.

On the wooden rafters are depicted tournament knights in early fourteenth-century armor with lance in rest on galloping horses.[30] On the cornice of the ceiling are depicted nine knights without armor, but with richly crested horses. These depicted figures, who originally must have numbered more than a hundred, are hoisting shields including one depicting the Roero coat of arms and another a large fleur-de-lis of France. Since the frescoes depict tournament scenes and chivalric exploits, Bera calls it the hall of "equestrian games."[31]

The coats of arms of the Roero family with the motto: "DE TOUT À SON PLAISIR" (everything to his liking) stand out all over the ceiling. Even the windows are completely frescoed with lozenges with heraldic lions inside. It is the most important 14th-century great hall in the city.[32]

Given the richness of the decorations, the knight with the fleur-de-lis, and the presence of a French motto other than that of the family, Bera surmises that this mansion may have been the lodging of Henry VII of Luxembourg who came to Asti in 1310 and stayed for nearly a month.[32]

Roero and Tomatis Palace of Chiusavecchia

Opposite the "house of equestrian games" is the palace that came to the Tomatis counts in the 18th century. This building, now completely remodeled, was part of a larger agglomeration that in its southern part was given to the Carmelites for their convent and the church of San Giuseppe.

The block, in its entirety, included Roero, Sella, and Scarampi streets, joining to the south in Piazza San Giuseppe.

This block was similar to the one opposite and, from the map of the Theatrum, the palaces of the Roero family of Poirino, the Roero family of Calosso, and the convent of the Carmelites are still noted in the 17th century.

The first properties used by the Carmelites must have belonged to the Roero Sanseverino family of Revigliasco.[33] To them belonged a decaying and abandoned three-story late medieval building with a tower, garden, portico, and colonnade.

On the second floor of the building, facing the street, was a gallery of five arches with four stone columns. Some halls had been used as mills in the past.

The first church of the order was made out of this palace, the consecration of which took place on August 12, 1646 while work was still in progress, completed in 1647.

The Carmelites also later built the monastery, owing to a gift in 1660 from Duke Charles Emmanuel II of Savoy of some houses he owned.[34] In late 1660, construction of the new church was begun on the existing structure. The facade was moved from the east to the south toward St. Martin's Gate. Work on the decorations and furnishings was completed in the late 18th century with funding from the Roero family, who held patronage over the high altar,[35] becoming their aristocratic church.[36]

Roero palaces on Via Q. Sella

Roero palace and tower in Cortanze

At number 21 on Via Q. Sella, at the corner of Via San Martino, divided from Palazzo Gazzelli by Via San Martino, is found this typical medieval palaxetum with a corner tower and inner courtyard. The exterior is well preserved and still has the floors bordered by the stringcourse and the round arched windows. The tower, lowered, belongs to the "second period" and measures 7.50 meters on a side. Of particular interest inside is a room with pointed vaults bordered by cylindrical ribs typical of medieval architecture of the 13th century.[37]

In the Archaeological Museum of St. Anastasius, there is a yellow sandstone cornerstone carved on two fronts from the palace and removed in the year 1890.

The stone, probably of French-Piedmontese workmanship, depicts a Gothic escutcheon with the Roero coat of arms, surmounted by a helmet with mantling and crest consisting of a rising donkey.

On the other shield, on the helmet the crest represented is a "Moor's head" framed by two large horns. It is one of the most important testimonies of the Asti courtly-chivalric civilization.[38]

Roero palaces in San Giuseppe square

Roero Palace later belonging to the Pelletta family of Cortazzone

It is an imposing building remodeled in the 17th century that faces the west side of San Giuseppe Square a few meters from San Martino Gate.

Of its medieval remains, the building has very well preserved a large trading depot that occupies the entire perimeter of the building.[39]

The large trading depot suggests that the building was probably a commercial construction of the family, used mainly as a warehouse and storage of goods in a strategic area of the city, a few hundred meters from the gate of San Martino and thus at a point of high density of passage.

In addition, its proximity to the canal and the Borbore also allowed the practical use of river traffic.[40] In the seventeenth century the building passed to the Pelletta family of Cortazzone, who began the work of modernization. The halls on the main floor were frescoed in the early 19th century with scenes on mythological subjects.

Roero Palace in the vicinity of Porta San Martino

On the corner of Piazza San Giuseppe and Via Grassi there is a medieval palace that Gabiani assumed was joined to the gateway through the bastions of the wall circle "of the nobles."[41]

The palace, with a quadrangular ground plan, is mostly covered by plaster, but still has an angle overlooking Piazza San Giuseppe, a large portal with a two-tone red-and-white ferrule and a round window, suggesting that the palace was built in the mid-13th century.[41]

It is speculated that this may have been the first house of the Roero family after their relocation from the houses in the San Paolo district.[42]

The angle positioned about 4 meters above the ground depicts in the center a flower grafting on a branch from which a pine cone emerges in relief. The upper part of the angle features a decoration of geometric notches. The side facing Via Grassi is engraved with a stylized wheel, possibly made at a later date when the house became the property of the Roero family.[43]

The fate of the Contrada

The collapse of the commune and the advent of the seigniories coincided with the decline of Asti's casane.

In 1369, there was still a debt of 10000 florins owed by Count Verde Amadeus VI of Savoy to Domenico and Guglielmo Roero,[44] in the face of a still active banking business.

Moreover, during the Orléans rule, there was a revival of the Asti leadership group. Louis d'Orleans, assuming the regency of the city, although on the one hand diminished its freedom, on the other hand increased its security and comforts.[45] With the exemption of some taxes and the creation in 1397 of the Molleggio society - a sort of ante-litteram joint-stock company devoted to the exploitation of the mills present along the course of the Borbore and the Triversa stream - he made the Asti nobles, who maintained a high economic standard during that period, participate.[46]

Almost a century later, the centralization of power of larger territorial aggregates led to an urban as well as economic decay of the city.

With the advent of Savoyard rule, the closure of all peripheral mints in the kingdom took place. Even the one in Asti was permanently closed around 1590 by Duke Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy.[47] In the period between the Hundred Years' War and the rule of Emmanuel Philibert, interspersed with continuous looting and foreign domination, the city had a long period of recession.[48]

Thus political decline coincided with economic decline: the great Asti families, including the Roero, with the establishment in 1575 of the Monte di Pietà, returned to their primary activity as landowners, scaling back their wealth and political power.[49]

Many "domus" went into decline either because of the exhaustion of the seigneurial line or because the city's leading figures bought large palaces in the Savoy capital and moved there, to make a life of court as diplomats, officials or ecclesiastical dignitaries. They left the management of the city of origin to cadet branches or new families.[50]

The contrada, after Napoleonic rule, lost many of its privileges, including that of prohibiting funeral transports and the passage of prisoners to reach jails.[51]

Via San Martino, the rear parallel of Via Roero that, starting from the church of the same name, descended skirting the palace and tower of the Roero family of Cortanze to arrive in Piazza San Giuseppe, was remembered as the street of the "lesa" (because being downhill, kids used it to "slide" during the winter months when it was covered in snow)[52] or the street of the "dead" (since funerals used to take place at the parish cemetery of San Martino in the 18th century).[53]

Many buildings were abandoned in the early 20th century. In the 1950s and 1960s, some became municipal or state property such as part of the Roero and Tomatis Palace in Chiusavecchia now housing the Gatti Middle School. Others are still being restored or consolidated, such as the Roero Palace in Settime and Mombarone, as part of a larger project of urban redevelopment of the city's historic center.

Image gallery

Roero Tower of Monteu, west side

Roero Tower of Monteu, west side Roero Tower of Monteu, west side window

Roero Tower of Monteu, west side window Roero Palace of Monteu, the alley where the small square of the church of San Martino once stood is visible

Roero Palace of Monteu, the alley where the small square of the church of San Martino once stood is visible Palace of the Roero family of Settime and Mombarone, rear entrance (via Asinari)

Palace of the Roero family of Settime and Mombarone, rear entrance (via Asinari) Roero palace, Malabayla street side

Roero palace, Malabayla street side Roero palace, corner with ruins of the corner tower

Roero palace, corner with ruins of the corner tower Tower and Roero house of Cortanze in Via Q. Sella, facade

Tower and Roero house of Cortanze in Via Q. Sella, facade Roero tower and house of Cortanze in Via Q. Sella

Roero tower and house of Cortanze in Via Q. Sella Roero house in Cortanze, via Q. Sella, corner of via san Martino

Roero house in Cortanze, via Q. Sella, corner of via san Martino House of the Roero family of Calosso and Cortanze, on Roero street, corner of Via Q. Sella, on the right the dome of the church of San Martino, on the left the Monteu Tower

House of the Roero family of Calosso and Cortanze, on Roero street, corner of Via Q. Sella, on the right the dome of the church of San Martino, on the left the Monteu Tower Roero palace and tower of Monticello and Piea

Roero palace and tower of Monticello and Piea Roero palace and tower of Monticello and Piea

Roero palace and tower of Monticello and Piea Roero House, Via Roero, corner of Via San Martino

Roero House, Via Roero, corner of Via San Martino Roero house on Via San Martino, detail of the sundial with the Roero coat of arms

Roero house on Via San Martino, detail of the sundial with the Roero coat of arms Roero Palace, later belonging to the Pelletta family of Cortazzone

Roero Palace, later belonging to the Pelletta family of Cortazzone Piazza san Giuseppe, on the left the Roero palace later belonging to the Pelletta family of Cortazzone, in the background, the ruins of Porta San Martino, on the right the Roero house in Via Grassi

Piazza san Giuseppe, on the left the Roero palace later belonging to the Pelletta family of Cortazzone, in the background, the ruins of Porta San Martino, on the right the Roero house in Via Grassi Roero House on Grassi Street

Roero House on Grassi Street Roero house on Grassi street, detail of the corner piece

Roero house on Grassi street, detail of the corner piece

See also

References

- ↑ Vergano 1953-1957, Vol 2, p. 174.

- ↑ Aldo di Ricaldone, Annali del Monferrato (951-1708). Roma 1987, p. 265

- ↑ Peyrot A., Asti e l'Astigiano, vedute e piante dal XIV al XIX secolo, Torino 1987. (Reproduction of a copper engraving by Jacopo Lauro called "Asti, Nobilissima città del Piemonte 1639" from Guido Antonio Malabaila's book, Compendio historiale della città d'Asti. Roma 1638), p. 54

- ↑ Dante Alighieri, Inferno - Canto VI

- ↑ Bera 2004, p. 824

- ↑ Camerana 1999, p. 291

- ↑ Gabrielli 1976, p. 212

- ↑ Bera 2004, p. 342

- ↑ Renato Bordone, Città e territorio nell'alto medioevo. La società astigiana dal dominio dei Franchi all'affermazione comunale. Biblioteca Storica Subalpina, Torino 1980, p. 190.

- ↑ Comitato Palio Rione S. Martino / S. Rocco. Il Borgo San Martino San Rocco nella storia di Asti. Ed. Comitato Palio SMSR, Asti, 1995

- ↑ Gabotto F., Le più antiche carte dell'archivio capitolare di Asti (Corpus Chart. Italiae XIX). Pinerolo Chiantore-Mascarelli 1904, doc. 16

- ↑ Guglielmo Ventura, in Chapter IV of his Memoriale referring to the year 1271, discusses the clashes between the Guelph faction of the Solaro and the Ghibelline faction of the Guttuari that led to the death and wounding of several Asti nobles. In 1272, the Astians stipulated a truce that lasted until 1300. Thereafter, clashes resumed and continued unrest forced the citizens of Asti to seek protection from the emperor (Gorrini G., Il comune astigiano e la sua storiografia. Firenze, Ademollo & c., 1884, p. 148).

- ↑ M.del Prete, L'aristocrazia bancaria astigiana. Vicende politiche ed economiche della famiglia Roero fino al 1330, dissertation, academic year 1991-1992.

- 1 2 3 Gabiani 1906

- ↑ Bera 2004

- ↑ G. Visconti, Diocesi di Asti e Istituti di vita religiosi, Asti 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Bordone 2001, p. 132

- ↑ Stefano Giuseppe Incisa, Giornale d'Asti, vol. 40, p. 148

- ↑ Incisa 1974, pp. 102-103

- ↑ The coat of arms of the Roero family of Asti was: a red shield with three silver wheels. The crest featured a wild man, armed with a club. On the cartouche the motto: A BON RENDRE, with variants: A BIEN RENDRE or A BUEN RENDRE (A. Manno, Il patriziato subalpino. Volume 26, p. 359 ).

- ↑ Malfatto 1982, p. 248

- 1 2 Bera 2004, p. 844

- ↑ Malfatto 1982, p. 249

- ↑ Gabiani 1906, p. 268

- ↑ Gabiani 1906, p. 271

- ↑ Bera 2004, pp. 829-830

- ↑ The codex from which the miniature was taken was commissioned by the emperor's brother, Baldwin of Luxembourg, archbishop of Trier (Peyrot A., Asti e l'Astigiano, tip. Torinese Ed., 1983).

- ↑ Quintino Sella, Codex Astensis, Volume 1, Roma tip. dei Lincei 1887, pag 118.

- ↑ Vergano 1953-1957, Vol. 3, p. 22.

- ↑ Bera 2004, p. 840

- ↑ Bera 2004, p. 842

- 1 2 Bera 2004, p. 837

- ↑ AA.VV., Ex Chiesa di San Giuseppe, Restauro e consolidamento artistico, Comune di Asti, Assessorato alla cultura.

- ↑ S.G. Incisa, Il giornale di Asti.

- ↑ Incisa 1974, p. 117

- ↑ Andrea M. Rocco, La chiesa di s.Giuseppe e i Roero nel XVIII secolo. Il Platano XVII, Asti, 1992, p. 97.

- ↑ Gabrielli 1976, p. 64.

- ↑ Bordone 2001, p. 193

- ↑ In the first centuries of the Middle Ages, private property extended only for buildings "from the ground to the sky," while cellars and underground buildings were state property. The people of Asti obviated this by constructing three-quarters basement rooms, with a single barrel vault supported by transverse arches, used as warehouses to store goods. The premises usually had three openings to the main street. The central opening was higher to allow people to pass through, the other two lower for loading and unloading goods (Bera 2004, p. 463)

- ↑ Bera 2004, p. 828

- 1 2 Gabiani 1906, p. 345

- ↑ Bera 2004, pp. 828-827

- ↑ Bera 2004, p. 541

- ↑ Quintino Sella, Codex Astensis. Memoria di Quintino Sella. Vol I, Roma, tip. della R. Accademia dei Lincei, 1887, p. 246.

- ↑ C. Vassallo, Gli astigiani sotto la dominazione straniera (1379 - 1531), saggio storico. Firenze, 1878, pag. 8.

- ↑ Fissore 2002, p. 57

- ↑ Bobba & Vergano, 1971

- ↑ A.M. Patrone, Le Casane astigiane in Savoia, Dep. subalpina di storia patria, Torino, 1959.

- ↑ Bordone 2005, p. 96

- ↑ Bordone 2005, p. 42

- ↑ Venanzio Malfatto, Asti nella storia delle sue vie, vol. II Savigliano 1979.

- ↑ U. Modulo, I borghi di San Martino e S.Rocco, Il Platano XII, Asti 1987, pag 6.

- ↑ Bianco 1960, p. 42

Bibliography

- Aldo di Ricaldone, Annali del Monferrato Vol I e II. Collegio Araldico di Roma- Se Di Co libraria L.Fornaca Asti 1987.

- Alfredo Bianco (1960). Asti medievale. Cassa di risparmio di Asti.

- Gianluigi Bera (2004). Asti edifici e palazzi nel medioevo. Asti: Gribaudo.

- Cesare Bobba; Ludovico Vergano (1971). Antiche zecche della provincia di Asti. Bobba.

- Renato Bordone (2001). Araldica astigiana. Allemandi.

- Renato Bordone (2005). Dalla carità al credito. C.R.A.

- A.S. Camerana (1999). "Le vie del sale, Roero. Castelli di Guarene, Monticello e Pralormo". In Francesco Gianazzo di Pamparato (ed.). Storia di famiglie e di castelli. Torino: Centro studi piemontesi.

- C. Cipolla, Appunti per la storia di Asti, 1891.

- Giuseppe Crosa, Asti nel Sette-ottocento. Lorenzo Fornaca editore-Gribaudo Asti, 1993.

- G.S. De Canis, Proposta per una lettura della corografia astigiana, C.R.A 1977.

- Ferro, Arleri, Campassi, Antichi Cronisti Astesi, ed. dell'Orso 1990 ISBN 88-7649-061-2.

- Gian Giacomo Fissore, ed. (2002). Le miniature del Codex Astensis. C.R.A.

- Niccola Gabiani (1906). Le torri le case-forti ed i palazzi nobili medievali in Asti. Brignolo.

- Niccola Gabiani, Asti nei principali suoi ricordi storici vol 1, 2,3. Tipografia Vinassa 1927-1934.

- F. Gabotto, Le più antiche carte dell'archivio capitolare di Asti (Corpus Chart. Italiae XIX). Pinerolo Chiantore-Mascarelli 1904.

- Noemi Gabrielli (1976). Arte e cultura ad Asti attraverso i secoli. Torino: Istituto Bancario San Paolo.

- G. Gorrini, Il comune astigiano e la sua storiografia. Firenze Ademollo & c. 1884.

- S. Grassi, Storia della Città di Asti vol I, II. Atesa ed. 1987.

- Stefano Giuseppe Incisa (1974). Asti nelle sue chiese ed iscrizioni. C.R.A.

- Venanzio Malfatto (1982). Asti antiche e nobili casate. Il Portichetto.

- A. Peyrot, Asti e l'Astigiano, tip.Torinese Ed. 1983.

- Q. Sella, Codex Astensis, Roma tip. dei Lincei 1887.

- S. Taricco, Piccola storia dell'arte astigiana. Quaderno del Platano Ed. Il Platano 1994.

- D. Testa, Storia del Monferrato.Lorenzo Fornaca editore Asti 1987.

- L. Vergano (1953–1957). Storia di Asti Vol. 1, 2, 3. Asti: Tipografia S. Giuseppe.