| Tourbillon Castle | |

|---|---|

Château de Tourbillon | |

| Sion | |

Tourbillon Castle | |

Tourbillon Castle  Tourbillon Castle | |

| Coordinates | 46°14′11″N 7°22′01″E / 46.236455°N 7.366948°E |

| Type | Castle Ruins |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Tourbillon Castle foundation |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1297–1308 |

| Built by | Boniface de Challant |

| Battles/wars | Raron affair (1417) |

| Official name | Tourbillon, ruines du château - Moyen Age |

| Reference no. | 7044 |

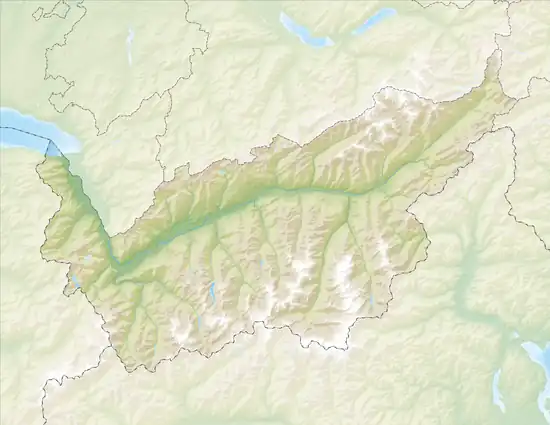

Tourbillon Castle (French: Château de Tourbillon) is a castle in Sion in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. It is situated on a hill and faces the Basilique de Valère, located on the opposite hill.

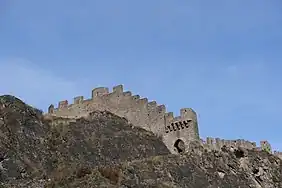

It was built at the end of the 13th century under the direction of Bishop Boniface de Challant. Of a defensive nature and perched on the top of a steep, rocky hill, it served as the residence of the bishops of Sion. The Tourbillon Castle was badly damaged by the conflicts between the bishops and the people of Valais. It was burnt down in 1417 during the Raron affair, a war between the people of Sion and the Raron family. It was rebuilt by Bishop William III of Raron some thirty years later. In 1788 it was completely destroyed by another fire. The stones of the castle were used for some time for construction in the region before the ruins were reinforced in the 19th century to make it a historical monument. The castle is a Swiss heritage site of national significance.

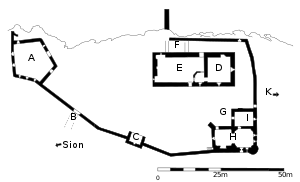

The castle is protected by nature; very steep terrain surrounds the structure. Accessible only from the east or west, it consists of a courtyard protected by surrounding walls. The castle has a keep, its own chapel and a garrison building.

Location

The Tourbillon Castle is located in Switzerland, in the canton of Valais, on the territory of the municipality of Sion. It is located on the Tourbillon hill and rises 182 meters (597 ft) above the city of Sion.[1] The hill consists of biogenic and clastic sedimentary rocks based on marly phyllites and calcareous shales.[2][3] The top of the hill forms a natural plateau with an average length of 200 m (660 ft) and a maximum width of 50 m (160 ft). The castle rests on the western part of the plateau, and its keep, in the center of the plateau, is located on a small rocky mound.[4]

History

Before the castle

The first known mention of the name "Tourbillon" dates back to 1268 in the form of "Turbillon". Its origin is not known, but there are two hypotheses proposed by the archaeologist François-Olivier Dubuis in 1960. The name could come from the terms "turbiculum" or "turbil," meaning "spinning top" or "small cone," or from a combination of the terms "turris," "tour," and the proper name "Billion" or "Billon," which appears in several documents from the thirteenth century.[5]

In 1994, excavations on the plateau east of the Tourbillon Castle revealed a Neolithic dwelling dated to the fifth millennium BC. Other discoveries, such as dry stone walls, prove that the castle site was used during the prehistoric period. In the nineteenth century, historians claimed that a Roman tower occupied the top of Tourbillon Hill before the construction of the castle. However, historians have never been able to prove the existence of this tower; the ruins that are supposed to be the foundations of the tower actually date back to the construction of the castle chapel in the Middle Ages.[6]

The Diocese of Sion was founded in Octodurum, now called Martigny in the early 4th century. In 589 the bishop, St. Heliodorus, transferred the see to Sion, as Octodurum was frequently endangered by the inundations of the Rhône and the Drance. Very little is known about the early Bishops and the early churches in Sion. However, in the late 10th century the last King of Upper Burgundy Rudolph III, granted the County of Valais to Bishop Hugo (998–1017). The combination of spiritual and secular power made the Prince-Bishops the most powerful nobles in the Upper Rhone valley. Sion became the political and religious center of the region. By the 12th century they began building impressive churches and castles in Sion to represent their power and administer their estates.[7] Valère, as the residence of the cathedral chapter in Sion, was one-third of the administrative center of the powerful Diocese of Sion. In the 12th century the Cathedral Notre Dame de Sion (du Glarier) was built in the town below Valère hill. The Cathedral became the seat of the Diocese of Sion, while the Prince-Bishop of Sion lived in the castle.[8]

Construction

The construction of Tourbillon castle is most probably linked to a major project to improve the fortifications of the town of Sion between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The beginning of the works is estimated at 1297 or 1298. They were supervised by Boniface de Challant, bishop of Sion at that time and descendant of the Viscounts of Aosta family. He imitated other members of his family, who had castles built in the Aosta Valley to strengthen their power on several occasions.[9]

Several deeds signed in Tourbillon as early as May 1307 show that the habitable parts of the castle were completed when Boniface died on 13 June 1308. However, according to the dating of some of the joists, it would appear that the castle was not completely finished at that time. It was therefore Boniface's successor and cousin, Aymon de Châtillon, who completed the work.[10]

Constant conflict

The Tourbillon Castle became the main residence of the Bishops of Sion from the time of its construction until Guichard Tavelli, who preferred the Soie Castle. After Tavelli bought Majorie Castle in 1373, Tourbillon became a temporary residence for the bishop but retained its military importance. On several occasions, Tourbillon was taken by force by Tavelli's enemies. On two occasions, the inhabitants of Sion laid siege to the castle and the bishop was forced to call for help from Amadeus VI of Savoy, who sent negotiators who managed to reach agreements with the people of Sion. A third conflict, this time with a nobleman from the Upper Valais named Pierre de la Tour, broke out in 1352 when he wanted to emancipate the bishop.[11] Pierre de la Tour's men set fire to a castle in Sierre and were arrested while trying to inflict the same fate on the castle of Tourbillon.[12] In exchange for the help of Amadeus VI, Tavelli offered the office of bailiff to the Count of Savoy. The latter appointed a vice-bailiff to administer the region and installed him in Tourbillon.[11]

This did not prevent new revolts, which were violently punished by Amédée VI; he ordered the town of Sion to be pillaged and partially burnt down. Although the castle was not affected by the revolts, the Count of Savoy asked the vice-bailiff to improve the defences of Tourbillon. The modifications included building new trebuchets, glacis at the bases of the castle walls and digging ditches on the plateau east of the castle. More than 5,000 crossbow bolts and several thousand trebuchet stones were stored in the castle, hoardings were built at the top of the castle walls and tower and the castle cistern was filled in the event of a siege.[13]

In March 1361, after nine years as bailiff, Amédée VI signed the Treaty of Evian and gave up interfering in the affairs of the bishop of Sion. In 1375, Guichard Tavelli was assassinated by supporters of Antoine de la Tour, son of Pierre, which led the Valaisans to ally themselves with Peter of Raron, a member of a powerful family from the Upper Valais who was a rival of the de la Tour family.[14][15] After having beaten Antoine de la Tour, the Valaisans, pushed by Peter of Raron, rose several times against the successor of Tavelli, Édouard de Savoie-Achaïe. In 1384, the Valaisans took over the Tourbillon, Majorie and Soie castles. Amedeus VII, a relative of Édouard de Savoie, laid siege to Sion and partially destroyed the town. Once the revolt had been brought under control, he imposed a severe peace treaty on the rebels allowing the bishop to recover his castles.[16][15] This did not prevent the bishop from leaving his post two years later, and it was not until 1392 that a unanimous candidate was found by the diocese of Sion.[17] Between the resignation of Édouard de Savoie-Achaïe and the election of the new bishop, the Count of Savoy made men available to guard the castle. As conflicts between the diocese and the people were still going on, the members of the diocese did not dare to show themselves in public, and they had to pay a chaplain to say mass in the Tourbillon chapel.[18]

Victim of the Raron affair

A final conflict took place at the beginning of the 15th century. Witschard of Raron, son of Peter, succeeded his father as Grand Bailiff, and the Raron family held the episcopal office, as two members of the family – William I in 1392, then William II, Witschard's uncle, in 1402 – succeeded each other at the head of the bishopric of Sion. The population then organised such a huge uprising that William II fled to the Soie Castle and Witschard went to Bern to seek help. Tourbillon and Montorge Castles were taken by force and then burnt down by the population in 1417.[19][20] Shortly afterwards, the Soie Castle was also besieged and destroyed and the bishop fled to Bern as well. The Bernese agreed to help the Raron, and their troops set fire to Sion in 1418. Peace was finally signed in 1420, and the Raron family regained all its rights.[20]

The castle of Tourbillon was in a pitiful state; its interiors and roofs were totally destroyed by fire and its walls were cracked in many places. It was therefore unusable.[21]

Return to peace and reconstruction

In 1418, André dei Benzi de Gualdo was appointed administrator of the diocese of Sion before becoming bishop in 1431 on the death of William II, who remained in Bern. He managed to restore peace, so that his successor, William III of Raron, nephew of William II, was accepted by the clergy and the people in 1437 despite belonging to the family of Raron.[22] In the years 1440 to 1450, de Gualdo organised the total reconstruction of Tourbillon Castle.[23] From that point the castle would no longer be subject to major modifications for several centuries, but was regularly maintained; it even withstood several armed conflicts in the 15th and 16th centuries. In the 17th century, it seems to have been used as a summer residence and, at the end of the century, it still seems to have been used for military purposes, mainly as a watchtower to warn the surrounding castles in the event of invasion.[24]

In the 18th century, the castle was used less and less, as its difficult access had led the bishops to look for houses elsewhere. Developments in siege warfare also meant that the castle was no longer of great strategic use. The Tourbillon castle was then emptied and was no longer guarded.[25]

The fire of 1788

On 24 May 1788, a fire broke out near the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Sion before being spread by a violent wind towards the north-east of the town. Although Valère Castle was spared, a large part of the town, including the Majorie Castle and Tourbillon, were seriously affected. In Tourbillon, all the woodwork – roofs, floors and furniture – disappeared entirely. The dungeon chambers were furnished with portraits of all the bishops of Sion, all of whom were lost in the fire. However, the lack of testimonies from the period makes it impossible to know the exact extent of the losses caused by the fire.[26]

With the destruction of the Majorie and de Tourbillon castles, the bishop of Sion was deprived of his residence in Sion. He quickly ordered the reconstruction of La Majorie, but left the renovation of Tourbillon for later, while ensuring that its walls did not collapse.[27] The various conflicts affecting the Valais finally left the bishopric of Sion without the resources needed to finance the work, and Tourbillon remained in ruins.[28] In the 19th century, when the Bishop of Sion Maurice-Fabien Roten had an episcopal palace built in Sion and abandoned the Majorie Castle, the materials remaining in Tourbillon – iron, stone slabs, etc. – were reused for other constructions, and the castle fell into oblivion.[29]

Conservation

In the second half of the 19th century, the people and authorities of the Valais began to worry about the conservation of the Tourbillon Castle. With financial assistance from the State, restoration projects were launched; the idea of restoring Tourbillon to its medieval appearance was soon abandoned as it was considered too costly. The castle walls were consolidated, the tower to the south of the enclosure was rebuilt and the wall in the north-west corner was partially destroyed and then rebuilt identically. The work was completed in 1887, and Tourbillon became a favourite destination for tourists and the people of Sion.[30]

The castle underwent several small arrangements over time: a small lodge was built in 1893 in the dovecote tower; in 1917 the watertightness of the chapel roof was reassured; in the 1930s, the north-east corner of the keep was rebuilt to support its eastern face.[31] Tourbillon Castle was recognised as a historical monument by the canton of Valais at the beginning of the 20th century.[32] In the 1960s, the condition of some of the masonry made tourist visits risky. In 1963, a Pro Tourbillon association was created and, two years later, the Swiss League for National Heritage organised the sale of a gold shield which enabled consolidation work to begin.[33] In 1970, Tourbillon was recognised as a monument of national importance. The last major consolidation work took place between 1993 and 1999.[34] In 1999, the Bishopric of Sion ceded the site to the Tourbillon Castle Foundation, and 400,000 francs were set aside by the Canton of Valais, the municipality of Sion and its bourgeoisie to maintain the castle.[35] Since 2009, the chapel has been undergoing restoration.[36]

The castle is open to the public with free admission from 15 March to 16 November.[37] An on-site guide is available to visit the chapel as well as for a guided tour of the castle ruins.[38] The castle is a Swiss heritage site of national significance.[39]

| 3D models of the Tourbillon Castle | |

|---|---|

In 2023, a 3D model of the castle was created by the Valais-Wallis Time Machine association. At a cost of 20,000 Swiss francs, this model enabled to visualise Tourbillon before the fire of 1788. The project is based on period sources as well as laser scanning and aerial and terrestrial photogrammetry. The model is available for free online, and has also been used to create a scale model.[40]

Description

Access and fortifications

Access to the Château de Tourbillon is either from the east or the west; the other sides of the hill are too steep. The western access is cut off by a fortification wall, equipped with a gate, which was most certainly overhung by a bypass, as the remaining machicolations and merlons suggest. To the north of the gate – thus higher up the hill – there is a semi-circular watchtower built into the wall. The wall once had a narrow sentry walk.[41]

- The castle fortifications to the west.

The fortifications of the western access seen from the outside.

The fortifications of the western access seen from the outside. The fortification gate of the western access.

The fortification gate of the western access. Path leading to the castle.

Path leading to the castle. The fortifications of the western access seen from the inside.

The fortifications of the western access seen from the inside.

The access to the east was also fortified, but the only remaining elements are ruins of walls pierced with narrow openings for archers.[42]

- The castle fortifications to the east.

The ruins of the fortifications of the eastern access.

The ruins of the fortifications of the eastern access..jpg.webp) The ruins of the fortifications of the eastern access.

The ruins of the fortifications of the eastern access.

Court

The main gate of the castle can be reached from the west access. Crossing this gate leads to a large courtyard bounded by a high crenellated wall. All of the castle buildings date from the construction of the castle in the 13th century and all of them, with the exception of the large tower to the north-east, are attached to the wall of the enclosure. The large main tower is similar to a dungeon and is divided into two parts: the bishop's flats to the east and a reception room to the west. To the west of the courtyard are the garrison quarters, to the south a corner tower, to the south-east a chapel, its sacristy and another corner tower, and to the north a cistern for use in case of siege.[43][44] To the east, a gate gives access to the rest of the plateau of the Tourbillon hill and to the ancient fortifications of the eastern access.[43]

- The buildings of the castle.

The garrison quarters.

The garrison quarters. The castle cistern.

The castle cistern. The corner tower to the south of the enclosure seen from the inside.

The corner tower to the south of the enclosure seen from the inside. The building housing the chapel and sacristy.

The building housing the chapel and sacristy. The corner tower to the south-east of the enclosure seen from the inside.

The corner tower to the south-east of the enclosure seen from the inside.

Keep

In the Middle Ages, the tower of the keep was covered with a pyramidal roof, and the reception room had a low-pitched gable roof. The tower included the bishop's room, which can be located thanks to a large window on the south side, and traces of a chimney remain, although it seems to have disappeared during the reconstruction of the 15th century.[45] At the same period, a floor was added to the keep, and a new staircase was built.[46] The original entrance to the building was on the north side, but was later moved to the south side. The reception room was lit by large low arched windows reminiscent of those in Chillon Castle. The large window on the west side of this room did not exist originally; it replaced two small openings during the reconstruction.[47]

- The castle's keep.

The keep as seen from south-west.

The keep as seen from south-west..jpg.webp) View from the north-west of the keep.

View from the north-west of the keep. Stairwell of the keep.

Stairwell of the keep. Interior of the keep

Interior of the keep

Chapel

Architecture

The chapel of Tourbillon Castle, dedicated to Saint George, is located to the south-east of the enclosure and consists of two bays; the one accessible from the north-west serves as the nave. Originally, the ceiling of the west bay was made of wood, but during one of the reconstructions it was reworked into a vaulted ceiling. The only opening on the south side dating from the construction of the building was an oculus, but subsequent renovation work has led to three other openings which make the oculus badly centred. The choir of the chapel is adorned by two tori resting on columns and has had a vaulted ceiling since its construction. This ceiling rests on a crossing of ogives.[48]

The north wall of the choir overlooks the sacristy. The sacristy is illuminated by three openings on the east wall – two lancets topped by an oculus – and by a group of lancets on the south wall; one of them, at man's height, was probably used for the defence of the castle. On the south wall are the remains of a liturgical pool.[49]

- The chapel of Tourbillon.

East bay of the chapel.

East bay of the chapel. Keystone to the Agnus Dei.

Keystone to the Agnus Dei.

Mural paintings

The Tourbillon Chapel has undergone two different cycles of mural paintings: one during its construction in the 14th century and the other in the 15th century. While the construction of the latter slightly damaged the former, it helped above all to preserve it.[50] For both cycles, the paintings were located in the same place: on the chevet wall, around the north and south windows of the chevet, on the south wall and around its windows, on the vault, on the north wall and finally on the triumphal arch.[51] The paintings in the first cycle depict various scenes, such as the Annunciation, the Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth or Saint George slaying a dragon.[50] The wall paintings of the second cycle also represent the Annunciation and Saint George, but also other saints that are more difficult to identify.[52]

- Mural paintings of the chapel.

Mural painting of King David from the first cycle.

Mural painting of King David from the first cycle. Mural painting of the Annunciation from the first cycle.

Mural painting of the Annunciation from the first cycle. Mural painting of the Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth.

Mural painting of the Crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth. Mural painting of Saint Sebastian and Saint Apollina from the second cycle.

Mural painting of Saint Sebastian and Saint Apollina from the second cycle. Mural painting of the coat of arms of the Raron family from the second cycle.

Mural painting of the coat of arms of the Raron family from the second cycle. Mural painting of Saint Fabian and Saint Catherine from the second cycle.

Mural painting of Saint Fabian and Saint Catherine from the second cycle.

References

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 240.

- ↑ "Groupes lithologiques sur la carte de Tourbillon". map.geo.admin.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- ↑ "Données géologiques sur la carte de Tourbillon". map.geo.admin.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 257.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 18.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 17–19.

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sion". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Sion". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Patrick Elsig (2000). Le château de Valère (in French). Sion: Sedum Nostrum. pp. 12–14.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 22–24.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 25–26.

- 1 2 Elsig 1997, p. 47–48.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 21.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 49–51.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 22.

- 1 2 Elsig 1997, p. 52.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 23.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 52–54.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 54.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 24.

- 1 2 Elsig 1997, p. 55–56.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 56.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 58.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 60.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 75–77.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 80–81.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 82–84.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 85.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 86-87.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 88.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 94–97.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 100–101.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 106.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 101–102.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 106–107.

- ↑ Vincent Gillioz (16 September 1999). Le Nouvelliste (ed.). "Histoire et avenir d'un château" (in French).

- ↑ "Les campagnes de restauration récentes". Château de Tourbillon (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ↑ "Château de Tourbillon – Bienvenue". Château de Tourbillon (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ↑ Sonia Bellemare (2 June 2010). "Il hante le château". Le Nouvelliste (in French). p. 27.

- ↑ "Kantonsliste A-Objekte". KGS Inventar (in German). Federal Office of Civil Protection. 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ Noémie, Fournier (2023-06-19). "Et si Tourbillon n'avait pas brûlé? Une reconstitution 3D montre à quoi ressemblait le château avant sa destruction". Le Nouvelliste (in French). Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 12.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 12, 16.

- 1 2 Elsig 1997, p. 17.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 51.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 28–29.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 60–63.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 29–30.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 33–35.

- ↑ Elsig 1997, p. 37.

- 1 2 Delaloye 1999, p. 7.

- ↑ Delaloye 1999, p. 7–15.

- ↑ Delaloye 1999, p. 8.

Bibliography

- Delaloye, Claire (1999). Les peintures murales du XVe siècle de la chapelle du château de Tourbillon (PDF) (in French). Genève: Université de Genève. p. 132.

- Elsig, Patrick (1997). Le château de Tourbillon (in French). Constantin. p. 112.

- Donnet, André; Blondel, Louis (1963). Châteaux du Valais (in French). Olten: Éditions Walter. p. 295.

External links

Media related to Château de Tourbillon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Château de Tourbillon at Wikimedia Commons