Royal Navy ranks, rates, and uniforms of the 18th and 19th centuries were the original effort of the Royal Navy to create standardized rank and insignia system for use both at shore and at sea.

History

Prior to the 1740s, Royal Navy officers and sailors had no established uniforms, although many of the officer class typically wore upper-class clothing with wigs to denote their social status. Coats were often dark blue to reduce fading caused by the rain and spray, with gold embroidery on the cuffs and standing collar to signify the officer's wealth and status. The early Royal Navy also had only three clearly established shipboard ranks: captain, lieutenant, and master. This simplicity of rank had its origins in the Middle Ages, where a military company embarked on ship (led by a captain and a lieutenant) operated independently from the handling of the vessel, which was overseen by the ship's master.

Over time, the nautical command structure merged these two separate command chains into a single entity with captain and lieutenant as commissioned officer ranks while sailing master (often shortened to simply "master") was seen as a type of warrant officer specializing in navigation and ship handling. In 1758, the rank of midshipman was introduced, which was a type of officer candidate position. The rank of "master and commander" (completely separate from the rank of master) first appeared in the 1760s and was originally a temporary appointment, rather than a substantive rank, whereby a lieutenant was appointed to command a vessels without a captain's commission (and the associated seniority and privileges). By the 1790s, the "master and commander" was routinely shortened to simply "commander" and was functionally a permanent rank. The practice of appointing lieutenants to command smaller vessels continued, however, and the term "lieutenant commanding" eventually evolved into the rank of "lieutenant commander."

Lord Anson first issued uniform regulations for naval officers in 1748; this was in response to the naval officer corps wishing for an established uniform pertaining to their service.[1] Officer uniforms were at first divided into a "best uniform", consisting of an embroidered blue coat with white facings worn unbuttoned with white breeches and stockings, as well as a "working rig" which was a simpler, less embroidered uniform for day-to-day use.

In 1767, the terms "dress" and "undress" uniform had been adopted and, by 1795, epaulettes were officially introduced. The epaulette style uniforms and insignia endured slight modifications and expansions until a final version appeared in 1846. In 1856, Royal Navy officer insignia shifted to the use of rank sleeve stripes – a pattern which has endured to the present day.

Ranks and positions

Naval ranks and positions of the 18th and 19th-century Royal Navy were an intermixed assortment of formal rank titles, positional titles, as well as informal titles used onboard oceangoing ships. Uniforms played a major role in shipboard hierarchy since those positions allocated a formal uniform by navy regulations were generally considered of higher standing, even if not by rank.

Shipboard hierarchy

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

In the 18th century Royal Navy, rank and position on board ship was defined by a mix of two hierarchies, an official hierarchy of ranks and a conventionally recognized social divide between gentlemen and non-gentlemen.[2] Royal Navy ships were led by commissioned officers of the wardroom, which consisted of the captain, his lieutenants, as well as embarked Royal Marine officers, all of whom were officers and gentlemen. The higher ranked warrant officers on board, the Sailing Master, Purser, Surgeon and Chaplain held a warrant from the Navy Board but not an actual commission from the Crown. Warrant officers had rights to mess and berth in the wardroom and were normally considered gentlemen; however, the Sailing Master was often a former sailor who had "come through the ranks" therefore might have been viewed as a social unequal. All commissioned and warrant officers wore a type of uniform, although official Navy regulations clarified an officer uniform in 1787 while it was not until 1807 that masters, along with pursers, received their own regulated uniform.[3]

Next came the ship's three "standing officers", the Carpenter, Gunner and Boatswain (Bo'sun), who along with the master were permanently assigned to a vessel for maintenance, repair, and upkeep. Standing officers were considered the most highly skilled seaman on board, and messed and berthed with the crew. As such, they held a status separate from the other officers and were not granted the privileges of a commissioned or warrant officer if they were captured.[3]

"Cockpit mate" was a colloquial term for petty officers who were considered gentlemen and officers under instruction and messed and berthed apart from the ordinary sailors in the cockpit. This included both midshipmen, who were considered gentlemen and officers under instruction, and master's mates, who derived their status from their role as apprentices to the sailing master. A midshipman outranked most other petty officers and lesser warrant officers, such as the Master-at-arms.[4][5] Boys aspiring for a commission were often called young gentlemen instead of their substantive rating to distinguish their higher social standing from the ordinary sailors.[6] Occasionally, a midshipman would be posted aboard a ship in a lower rating such as able seaman but would eat and sleep with his social equals in the cockpit (all Midshipman would be 'rated able' at some point in their service – it was a requirement for them to have been so before they could stand as a Mate, another requirement for promotion to Lieutenant).[7][N 1]

The remainder of the ship's company, who lived and berthed in the common crew quarters, were the petty officers and seamen. Petty officers were seamen who had been "rated" to fill a particular specialist trade on board ship. This rating set the petty officers apart from the common seaman by virtue of technical skill and slightly higher education. No special uniform was allocated for petty officers, although some Royal Navy ships allowed such persons to don a simple blue frock coat to denote their status.

Seamen were further divided into two grades, these being ordinary seaman and able seaman. Seamen were normally assigned to a watch, which maintained its hierarchy consisting of a watch captain in charge of a particular area of the ship. Grouped among the watches were also the landsmen, considered the absolute lowest rank in the Royal Navy and assigned to personnel, usually from press gangs, who held little to no naval experience.

Enlisted seamen and marines discharged due to disability or advanced age could be admitted to the Royal Hospital, Greenwich. From 1805 until 1869, pensioners were issued with a distinctive uniform comprising a blue frock coat with brass buttons, white waistcoat and pantaloons, black shoes, and a tricorn hat similar to those issued to their army counterparts at Chelsea.[9]

Minors in the Royal Navy

Until the child labour laws of the late 19th century, poor children started work as soon as they were able.[10] Child labour was considered both necessary and desirable; being good for the child's development and providing additional income to struggling families.[11] From the ages of five or six, farmers' children would assist with the sowing and gathering crops while a chimney sweep's climbing boy might be as young as three or four.[12][13] The view that child labour was both morally and legally acceptable was prevalent not just in Britain but throughout the world's most advanced nations.[14]

The Royal Navy was not exceptional in its employment of young boys, who were rated in three classes: A Boy Third Class was under 15 and was usually employed as an officer's servant, a Boy Second class was between 16 and 18 and undertook normal seaman's duties. Boy First Class was a rating reserved for those training to become officers; usually young gentlemen from well-to-do families.[15][16] This was a popular and recognised route, offering an opportunity to accumulate knowledge and sea time, prior to becoming a midshipman. Service as a ship's boy was recorded as sea-service; officers' servants could obtain credit towards the mandatory six years of sea time needed before attempting the lieutenant's exam.[17] It was not uncommon for these boys to be signed on in name only while they remained on land at school, high-ranking officers supplying fictitious seatime in exchange for some reward or favour.[18]

The number of second and third class boys allowed on each ship was dictated by the Admiralty and could be as many as 13 and 19 respectively for first rate ships while a large frigate might have 10 third class and six second class.[16] The youngest were not supposed be less than 13, or 11 if they were the son of an officer, but this rule was often broken.[19] The Marine Society, founded in 1756 by Jonas Hanway, was a charity that encouraged poor and destitute young boys to seek a better life in the navy. The society provided food, clothing and bedding, and an education which included basic seaman skills. At its peak, in the 1790s, it was providing 500 to 600 boys a year for the Royal Navy.[20]

Once a boy, further advancement could be obtained through various specialties. A cabin boy assisted with the ship's kitchen, as well as other duties, while a powder monkey helped in the ship's armoury. After the Age of Sail ended, the position of ship's boy became an actual Royal Navy rank known as "boy seaman".

| Position | Status | Appointing Agency | Messing & berthing | Uniform | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commodore | Commissioned officer | Admiralty | Great Cabin | Blue frock coat with gold laced buttons.[N 2] | Special grade for captains in charge of multiple vessels[N 3] |

| Captain | Vessel commanding officer | ||||

| Commander | Blue frock coat white waist coat.[N 4] | Non-rated ship captain. (Full title "master and commander") | |||

| Lieutenant | Wardroom | Division officer/watch officer | |||

| Acting lieutenant | Warrant officer | Ship's captain | No established uniform (recipients would wear the uniform of the last grade held) | Later known as sub-lieutenant[N 5] | |

| Master | Navy Board | Blue frock coat with gold Navy buttons | Highest ranked warrant officer on board | ||

| Purser | Victualling Board | Ship's accountant, responsible for supplies | |||

| Surgeon | Sick and Hurt Board | Ship's medical officer | |||

| Chaplain | Church of England | Only present on larger vessels | |||

| Midshipman | Cockpit officer | Various methods for appointment | Cockpit | Blue frock coat, white button collar patch | Officer candidate position |

| Midshipman's mate | Cockpit mate | Blue frock coat with white trim | Special grade reserved for master's mates who had passed the examination for lieutenant | ||

| Master's mate | Could also be rated as "second master" | ||||

| Surgeon's mate | Sick and Hurt Board[N 6] | Ship's medic on smaller vessels | |||

| Captain's Clerk | Civilian | Typically hired by captain | Civilian clothing | Clerical duties on board ship | |

| School teacher | Only present on larger ships. Primary duty to instruct midshipmen in academic matters | ||||

| Steward | Crew's messing and berthing | A more senior cook and servant, usually reserved for flagships and larger vessels | |||

| Cook | Normally an older retired or injured seaman | ||||

| Gunner | Standing officer | Shipboard appointment by captain | Blue frock coat with Navy buttons | In charge of all ship's armaments | |

| Boatswain | Most experienced deck seaman aboard | ||||

| Carpenter | Shipboard issued crew clothing | Head of the carpenter's team | |||

| Armourer | Petty officer | Senior petty officers | |||

| Ropemaker | |||||

| Caulker | |||||

| Master-at-arms | |||||

| Sailmaker | Mid-grade petty officer | ||||

| Yeoman | Two on board: Yeoman of the sheets & yeoman of the powder room | ||||

| Coxswain | Deck hand specialist petty officer | ||||

| Quartermaster | Helmsman on board the ship serving watch at the ship's wheel | ||||

| Cooper | Worked directly for the ship's purser | ||||

| Ship's corporal | Assistant to the master-at-arms | ||||

| Watch captains | Experienced seaman in charge of a watch team | ||||

| Armourer's mate | Junior petty officer | ||||

| Gunner's mate | |||||

| Boatswain's mate | |||||

| Caulker's mate | |||||

| Carpenter's mate | |||||

| Sailmaker's mate | |||||

| Quartermaster's mate | |||||

| Gunsmith | Seaman | Seaman specialists | |||

| Quarter gunner | |||||

| Carpenter's crew | |||||

| Able seaman | Seaman with more than three years experience | ||||

| Ordinary seaman | Seaman with at least one year experience | ||||

| Landsman | Seaman with less than one year experience | ||||

| Boy | Servant | Lowest possible position on board, normally held by boys 12 years or younger. |

Promotion and advancement

Promotion and advancement within the 18th and 19th century Royal Navy varied depending on the status of the sailor in question. At the lower levels, most inexperienced sailors began in the rank of landsman – those joining ships at a very young age were typically entered in the navy as cabin boys or officers' servants.

After a year at sea, landsmen were normally advanced to ordinary seaman. Three more years, with appropriate ability displayed, would see a sailor advanced to able seaman. For the "common seaman", this level is where the career path usually ended, and many sailors spent their entire Royal Navy careers as able seaman on various vessels.

Advancement into the petty officer positions required some level of technical skill. A ship's captain typically made petty officer appointments – sailors could also be "rated on the books" as a petty officer when a ship was in port searching for a crew[N 7] Honesty was implied, as a sailor falsely claiming experience in order to rate a billet on board ship would be quickly discovered once at sea.

Senior petty officers could also be rated as a standing officer, of which only three such positions normally existed (boatswain, carpenter, and gunner). These were highly coveted positions since Standing officers were highly valued due to their skill and experience. Additionally the Standing Officers remained with a vessel, and continued to be paid, during lay-up and maintenance, whereas the rest of the officers and crew would often be discharged and lose their income if they could not find another ship to join.

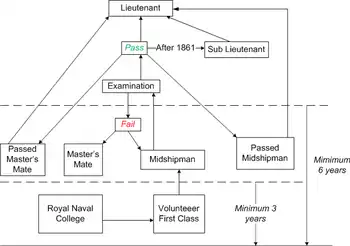

Warrant officers were given their positions by various certification boards and had nearly the same rights and respect as commissioned officers, including access to the quarterdeck and wardroom. Advancement into the commissioned officer grades required a royal appointment, following a certification by the lieutenant's examination board. Board eligibility was most often achieved by serving as a midshipman, although the career path of a master or master's mate also permitted this opportunity.

Once commissioned, lieutenants would be rated onboard based on seniority, such as "1st lieutenant", "2nd lieutenant", "3rd lieutenant", etc. with the 1st lieutenant filling the modern-day role of executive officer and second-in-command. Lieutenants, like ordinary sailors, were required to be signed on to various vessels due to manpower needs. If a lieutenant could not find a billet, the officer was said to be on "half-pay" until a sea billet could be obtained.

The title of commander was originally[21] a temporary position for lieutenants placed in charge of smaller vessels. Successful commanders (who were known by courtesy on board their ships as "captain") could aspire for promotion to captain which was known as "making post". Such post captains were then assigned to-rated vessels in the rating system of the Royal Navy. Once a captain, advancement to admiral was strictly determined by seniority – if a captain served long enough for more senior officers to retire, resign, or die, he would eventually become an admiral. One distinguishing element among captain was, however, determined by the rating of the vessel they commanded. The captain of a sixth rate, for instance, was generally junior to a captain of a first-rate.

Watch organization

Royal Navy vessels operated on a number of parallel hierarchies in addition to formal ranks and positions, paramount of which was the vessel's watch organization.[22] Watches were stood 24 hours a day and divided into "watch sections" each of which was led by an "officer of the watch", typically a lieutenant, midshipman, or master's mate (the captain and master did not stand watch but were on call 24 hours a day)

The heart of the watch were the watch teams, each led by a petty officer known as a captain (separate entirely from the vessel's commanding officer). There were six watch teams on most Royal Navy vessels, divided into three "deck" teams and three "aloft" teams. The aloft teams were manned by sailors known as "topmen" and were considered the most experienced men aboard. In all, the six watch teams were as follows:

- Aloft: Fore topmen, main topmen, mizzen topmen

- Deck: Forecastle men, waisters, afterguard

A special watch team of quartermasters handled the navigation and steering of the vessel from the quarterdeck. Furthermore, the ship's boatswain and his mates were interspersed among the various watch teams to ensure good order and discipline. The remainder of the ships' company, who did not stand a regular watch, included the ship's carpenter's crew and the gunnery teams (in charge of the maintenance of the ship's guns). Any other person on board who did not stand watch was collective referred to as an "idler" but was still subject to muster when the "all hands on deck" was called by the boatswain.

Quarters and stations

In addition to the standard watch organisation of a Royal Navy vessel, additional organisational hierarchies included the division, headed by a lieutenant or midshipman, mainly to muster, mess, and berth; divisions were typically present only on the larger rated vessels.

The term "Action Stations" was a battle condition in which a Royal Navy vessel manned all of its guns with gun crews, stood up damage control and emergency medical teams, and called the ship's senior officers to the quarterdeck in order to direct the ship in battle. A sailor's action station was independent of their watch station or division, although in many cases groups of sailors manning the same action station were assigned from the same division or watch section.

A unique readiness condition of some Royal Navy vessels was known as "in ordinary". Such vessels were usually permanently moored with masts and sails removed and manned only by a skeleton crew. In ordinary vessels did not maintain full watch sections and were normally maintained as receiving ships, shore barges, or prison ships.

Chronology of uniforms

1748–67

The first uniforms of the Royal Navy were issued to commissioned officers only and consisted of a blue dress uniform or 'suit', which featured 'boot cuffs'; based upon formal court wear of the time, and a 'frock', which was a simpler uniform that featured 'mariners cuffs' which were used to turn back the cuffs of the coat when strenuous or dirty work was being done. The frock also featured (unlike the single-breasted suit) double-breasted lapels that could be worn either buttoned back or worn buttoned across the chest to protect the wearer from the elements.

Both the dress suit and frock worn by lieutenants were rather plain, the dress suit featuring plain white boot cuffs and the frock being plain blue with no other distinction. Although included in the 1748 dress regulations, midshipmen were only issued with a frock to act as an all-purpose uniform. This featured (from 1758) the white 'turnback' that is still used as rank insignia for midshipmen to the present day. Both the dress 'suit' and undress 'frock' uniforms were worn with blue breeches and black cocked hats; which were gold-laced and featured a black cockade.

1767–1774

The next major change in Royal Navy uniforms occurred in 1767 when the dress uniform 'suit' was abolished, and the frock became an all-purpose uniform. This state of affairs continued until 1774; when the former frock became the full dress uniform, and a new working or 'undress' uniform was introduced. Enlisted sailors had no established uniform, but were often issued standardised clothing by the ship on which they served to create a uniform appearance among seaman.

1774–1787

In this year the former 'all-purpose' uniform became full dress. A simpler blue 'frock' was introduced for everyday purposes. In 1783, flag officers were granted a new full-dress uniform; again a heavily embroidered single-breasted coat as before, but for the first time denoted what rank the bearer was by stripes on the cuffs; three for Admirals, two for vice admirals, and one for rear admirals.

1787–1795

1787 saw the slashed cuffs of the full-dress for commissioned officers replaced with white round cuffs with three buttons (the lapels and cuffs were blue for Masters and Commanders). For flag officers, the embroidery on the coat and cuffs was replaced with lace. This year also saw Warrant officers (Masters, Surgeons, Pursers, Boatswains, and Carpenters) being granted a standardised, plain blue uniform as well. Midshipmen's cuffs were changed from slashed cuffs to blue round cuffs with three buttons as well.

1795–1812

The most significant uniform change of the late 1700s was on 1 June 1795 when flag officers, captains and commanders were granted epaulettes.[23] Uniforms for all ranks lost their white facings.[24] Over the next fifty years, epaulettes were the primary means of determining officer rank insignia. Surgeons, who had hitherto worn the standard warrant officer's uniform, were, in June 1805, given waistcoat and breeches, a blue, single-breasted coat with white lining, standing collar and eight buttons for dress occasions. An undress coat was also provided which had a falling collar and no cuff or pocket buttons.[25] A full-dress uniform for pursers and masters was introduced in June 1807.[25]

1812-1827

From March 1812 the full-dress uniform reinstated the white lapels, collars and cuffs that had been replaced by blue in 1795, except on the undress uniform.[23] Midshipmen also retained the all blue jacket[26] and the captain's uniform was now double-breasted.[27] Lieutenants were granted a single gold epaulette on the right-hand side.[23] In 1812, the fouled anchor insignia on uniform buttons was topped with a crown.[28]

1825-1827

1825 saw the introduction of the 'undress tailcoat'; which was a blue tailcoat, similar to that worn by civilians at the time, that was worn with the epaulettes.

1827-1830

A radical change in the full-dress coat occurred in 1827 when a new pattern was introduced that was very similar to the undress coat of the 1812-1825 pattern. Instead of sloping away from the chest, the tails of the coat were now cut away at the waist (like a modern-day civilian tailcoat) and were ordered to be buttoned up at all times. Midshipmen, Masters, Volunteers of the First and Second class and Surgeons were to keep their existing uniforms but were to wear them fully buttoned up. In 1827, regulations; there was ordered to be no distinction between full dress and undress, the only distinction between the two being that officers were allowed to wear plain blue trousers in undress. In 1829, however, a single-breasted frock coat was allowed to officers for wear in the vicinity of their ships. This featured sleeve lace to denote rank: a braid for midshipmen and mates, two stripes for lieutenants, two stripes for commanders, and three stripes for captains. Flag officers were to wear their epaulettes with the frock coat. This garment was worn with plain blue trousers and a peaked cap by all officers. Although short-lived (it was abolished in 1833), this frock-coat was an important precursor and influence on later styles of uniform, particularly in undress.

1830-1843

In 1830, the facings of the full-dress coat were changed from white to scarlet. This was the case until 1843.

1843-1846

1843 saw the return of white facings to the full dress uniforms of commissioned officers. Lieutenants were granted two plain epaulettes in place of the former one.

1846-1856

1847 saw the adoption of a double-breasted frock coat, worn in undress that featured rank lace on the sleeves similar to the single-breasted frock coat of the 1820s and 30s. This could be worn either with the peaked cap or with the cocked hat, sword and sword belt for more formal occasions.

Sleeve stripes were introduced for full dress and on the undress tailcoat for all commissioned officers as well from 1856.

After 1856

Although they had always been authorized for undress uniforms, 1878 saw a clarification of the wearing of cuff buttons worn on the undress coats (the frock coat and undress tailcoat) this were worn beneath the cuff stripes. For flag officers, the buttons were worn between the thicker line of braid and the thinner ones above. 1880 saw the introduction of the 'ship jacket' (similar to today's reefer jacket) for wear at night or in inclement weather in undress. In 1885, a white tunic, worn with white trousers and white sun helmet and black boots, was introduced for wear in hot climates, as well as a navy blue tunic and trousers, of the same cut, for wear in undress in temperate climates. On both garments, rank was initially worn on the sleeve: in white silk for the white uniform, in gold for blue. The reefer jacket replaced the blue tunic in 1889. The white tunic was redesigned at the same time, with rank being worn on shoulder-boards instead of the sleeve.

Flag officers

Flag rank advancement in the 18th and 19th century Royal Navy was determined entirely by seniority. Initial promotion to flag rank from the rank of captain occurred when a vacancy appeared on the admirals' seniority list due to the death or retirement of a flag officer. The captain in question would then be automatically promoted to rear admiral and assigned to the first of three coloured squadrons, these being the blue, white and red squadrons.

As further vacancies occurred, the British flag officer would be posted to the same rank in higher squadrons. For instance, a rear admiral of the blue squadron would be promoted to become rear admiral of the white, and then rear admiral of the red squadron. When reaching the highest position of the rank (rear-admiral of the red), the flag officer would next be promoted to the rank of vice admiral, and begin again at the lowest coloured squadron (vice-admiral of the blue). The process would continue again, until the vice-admiral of the red was promoted to admiral of the blue. The highest possible rank was admiral of the red squadron, which until 1805 was synonymous with admiral of the fleet (originally this rank wore the same insignia as a regular admiral – a special insignia was first created in 1843).

Situations did occur where flag officers would "jump" to a higher rank in a different squadron, without serving their time in each rank of each squadron. Such was the case with William Bligh, who was promoted directly from rear admiral to vice-admiral of the blue without ever having served as a rear-admiral of the red or white squadron. On the opposite, a higher-ranked admiral in a lower squadron (i.e. vice-admiral of the blue) could not be demoted to a lower rank yet in a higher rated squadron (i.e. rear admiral of the red).

Some flag officers were not assigned to a squadron and thus were referred to simply by the generic title "admiral". Formally known as "admiral without distinction of a squadron", the common term for such officers was "yellow admiral". Still another title was port admiral which was the title for the senior naval officer of a British port.

Notes

- ↑ Horatio Nelson served as an able seaman aboard the Seahorse,[7] and Peter Heywood served as an able seaman aboard HMS Bounty.[8]

- ↑ After 1795, blue coat with epaulettes

- ↑ Commodores second class commanded their own vessels while commodores first class were appointed a captain to command their flagship

- ↑ After 1795 (Commander) and 1812 (Lieutenant), blue coat with epaulettes

- ↑ Acting lieutenants were normally senior midshipman who were granted wardroom status due to their tenure and experience, although the designation was also extended on occasion to masters and master's mates. One historical case of a master's mate appointed as an acting lieutenant was that of Fletcher Christian, appointed by William Bligh much to the derision of John Fryer, master of the Bounty.

- ↑ In some cases, surgeon's mates were appointed aboard by the commanding officer, usually in remote or distant settings where a formal appointment was not possible

- ↑ Unlike modern day navies, the Royal Navy of the 18th and 19th century did not maintain a standing enlisted force. Sailors were signed onto ships in port in order to fill manning requirements.

References

- ↑ "National Maritime Museum". www.nmm.ac.uk. National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Lewis 1939, p. 228

- 1 2 Blake & Lawrence 2005, p. 71

- ↑ Lewis 1939, p. 270

- ↑ Lavery 1989, p. 270

- ↑ Blake & Lawrence 2005, p. 72

- 1 2 Lewis 1939, p. 267

- ↑ "Pitcairn Crew". Pitcairn Island Study Center. 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Jack Tar: Life in Nelson's Navy (2008), by Roy and Leslie Adkins, page 389

- ↑ Emma Griffin (2014). "Childhood and Childrens Literature". British Library. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "Child Labour in Historical Perspective" (PDF). UNICEF. 1996. p. 41. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "The Struggle for Democracy - Child Labour". House of Lords Records office. 1996. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ Jessica Brain (2021). "Chimney Sweeps' Climbing Boys". Historic UK. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "Child Labour in Historical Perspective" (PDF). UNICEF. 1996. p. 8. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ Lavery p. 129

- 1 2 Lavery p. 138

- ↑ Rodger p. 263

- ↑ Blake & Lawrence p. 72

- ↑ Rodger p. 27

- ↑ Lavery p. 124

- ↑ N.A.M. Rodger (2001) Commissioned officers' careers in the Royal Navy, 1690–1815, Journal for Maritime Research, 3:1, 85-129, DOI: 10.1080/21533369.2001.9668314

- ↑ O'Neill 2003, p. 75

- 1 2 3 Blake & Lawrence pp.75-79

- ↑ Blake & Lawrence pp. 74 - 79

- 1 2 Blake & Lawrence p. 70

- ↑ Blake & Lawrence p. 73

- ↑ Blake & Lawrence p. 77

- ↑ Blake & Lawrence p. 68

Sources

- Blake, Nicholas; Lawrence, Richard (2005), The Illustrated Companion to Nelson's Navy, Stackpole Books, ISBN 0-8117-3275-4, OCLC 70659490

- Lavery, Brian (1989), Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-258-3, OCLC 20997619

- Lewis, Michael (1939), England's Sea-Officers, London: George Allen & Unwin, OCLC 1084558

- O'Neill, Richard (2003), Patrick O'Brian's Navy, London: Salamander Books, ISBN 0-7624-1540-1

- Roger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World - An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. London: Fontana Press. ISBN 978-0-00-686152-2.