Replica of Bounty, built in 1960 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Bethia |

| Owner | Private merchant service |

| Builder | Reputedly Blaydes Yard, Kingston-upon-Hull, England |

| Launched | 1784 |

| In service | 1784–1787 |

| Fate | Sold to the Royal Navy, 23 May 1787 |

| Name | Bounty |

| Cost | purchased for £1,950 |

| Acquired | 23 May 1787 |

| Commissioned | 16 August 1787 |

| In service | 1787–1790 |

| Fate | Burned by mutineers, 23 January 1790 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tons burthen | 22026⁄94 (bm) |

| Length | 90 ft 10 in (27.7 m) |

| Beam | 24 ft 4 in (7.4 m) |

| Depth of hold | 11 ft 4 in (3.5 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 44 officers and men |

| Armament |

|

_RMG_D3970_2.jpg.webp)

_RMG_D3970_3.jpg.webp)

HMS Bounty, also known as HM Armed Vessel Bounty, was a British merchant ship that the Royal Navy purchased in 1787 for a botanical mission. The ship was sent to the South Pacific Ocean under the command of William Bligh to acquire breadfruit plants and transport them to the British West Indies to provide a cheap food source for the West Indies' large enslaved population. That mission was never completed owing to a 1789 mutiny led by acting lieutenant Fletcher Christian, an incident now popularly known as the Mutiny on the Bounty.[1] The mutineers later burned Bounty while she was moored at Pitcairn Island in the Southern Pacific Ocean in 1790. An American adventurer helped land several remains of Bounty in 1957.

Origin and description

Bounty was originally the collier Bethia, which was reportedly built in 1784 at Blaydes Yard in Hull, Yorkshire. The Royal Navy purchased her for £1,950 on 23 May 1787 (equivalent to £222,000 in 2019), and subsequently refitted the ship and renamed her Bounty.[2] The ship was relatively small at 215 tons, but had three masts and was full-rigged. After conversion for the breadfruit expedition, she was equipped with four 4 pdr (1.8 kg)[5] cannon and ten swivel guns.

1787 breadfruit expedition

Preparations

The Royal Navy had purchased Bethia for the sole purpose of carrying out the mission of acquiring breadfruit plants from Tahiti, which would then be transported to the British West Indies as a cheap source of food for the region's slaves. Sugar, produced by slave labor, was by far the West Indies' biggest cash crop, and was then one of the world's most lucrative traded commodities.[6] Sugar was cultivated under conditions so harsh and extreme that enslaved people survived an average of just seven years following arrival on West Indies plantations.[7] English naturalist Sir Joseph Banks originated the breadfruit idea and promoted it in Britain, recommending Lieutenant William Bligh to the Admiralty as the mission's commander. Bligh, in turn, was promoted in rank via a prize offered by the Royal Society of Arts.[8]

In June 1787, Bounty was refitted at Deptford. The great cabin was converted to house the potted breadfruit plants, and gratings were fitted to the upper deck. William Bligh was appointed commanding lieutenant of Bounty on 16 August 1787 at the age of 33, after a career that included a tour as sailing master of the sloop Resolution during the third voyage of James Cook, which lasted from 1776 to 1780. The ship's complement consisted of 46 men, with Bligh as the sole commissioned officer, two civilian gardeners to care for the breadfruit plants and the remaining crew consisting of enlisted Royal Navy personnel.[9]

Voyage out

On 23 December 1787, Bounty sailed from Spithead for Tahiti. For a full month, the crew attempted to take the ship west, around South America's Cape Horn, but adverse weather prevented this. Bligh then proceeded east, rounding the southern tip of Africa (Cape Agulhas) and crossing the width of the Indian Ocean. During the outward voyage, Bligh demoted Sailing Master John Fryer, replacing him with Fletcher Christian . This act seriously damaged the relationship between Bligh and Fryer, and Fryer later claimed that Bligh's act was entirely personal.

Bligh is commonly portrayed as the epitome of abusive sailing captains, but this portrayal has recently come into dispute. Caroline Alexander points out in her 2003 book The Bounty that Bligh was relatively lenient compared with other British naval officers.[10] Bligh enjoyed the patronage of Sir Joseph Banks, a wealthy botanist and influential figure in Britain at the time. That, together with his experience sailing with Cook, familiarity with navigation in the area, and local customs were probably important factors in his appointment.[11]

Bounty reached Tahiti, then called "Otaheite", on 26 October 1788, after ten months at sea. The crew spent five months there collecting and preparing 1,015 breadfruit plants to be transported to the West Indies. Bligh allowed the crew to live ashore and care for the potted breadfruit plants, and they became socialised to the customs and culture of the Tahitians. Many of the seamen and some of the "young gentlemen" had themselves tattooed in native fashion. Master's Mate and Acting Lieutenant Fletcher Christian married Maimiti, a Tahitian woman. Other warrant officers and seamen were also said to have formed "connections" with native women.[12]

Mutiny and destruction of the ship

_RMG_S0713_(cropped).jpg.webp)

After five months in Tahiti, Bounty set sail with her breadfruit cargo on 4 April 1789. Some 1,300 mi (2,100 km) west of Tahiti, near Tonga, mutiny broke out on 28 April 1789. Despite strong words and threats heard on both sides, the ship was taken bloodlessly and apparently without struggle by any of the loyalists except Bligh himself. Of the 42 men on board aside from Bligh and Christian, 22 joined Christian in mutiny, two were passive, and 18 remained loyal to Bligh.

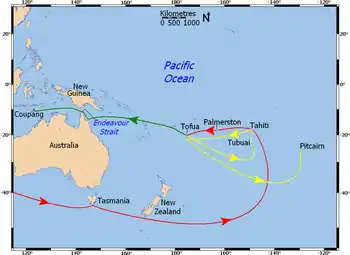

The mutineers ordered Bligh, two midshipmen, the surgeon's mate (Ledward), and the ship's clerk into the ship's boat. Several more men voluntarily joined Bligh rather than remain aboard. Bligh and his men sailed the open boat 30 nmi (56 km) to Tofua in search of supplies, but were forced to flee after attacks by hostile natives resulted in the death of one of the men.

Bligh then undertook an arduous journey to the Dutch settlement of Coupang, located over 3,500 nmi (6,500 km) from Tofua. He safely landed there 47 days later, having lost no men during the voyage except the one killed on Tofua.

The mutineers sailed for the island of Tubuai, where they tried to settle. After three months of bloody conflict with the natives, however, they returned to Tahiti. Sixteen of the mutineers – including the four loyalists who had been unable to accompany Bligh – remained there, taking their chances that the Royal Navy would not find them and bring them to justice.

HMS Pandora was sent out by the Admiralty in November 1790 in pursuit of Bounty, to capture the mutineers and bring them back to Britain to face a court martial. She arrived in March 1791 and captured fourteen men within two weeks; they were locked away in a makeshift wooden prison on Pandora's quarterdeck. The men called their cell "Pandora's box". They remained in their prison until 29 August 1791 when Pandora was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef with the loss of 35 lives, including four mutineers (Stewart, Sumner, Skinner, and Hildebrand).

Immediately after setting the sixteen men ashore in Tahiti in September 1789, Fletcher Christian, eight other crewmen, six Tahitian men, and 11 women, one with a baby, set sail in Bounty hoping to elude the Royal Navy. According to a journal kept by one of Christian's followers, the Tahitians were actually kidnapped when Christian set sail without warning them, the purpose of this being to acquire the women. The mutineers passed through the Fiji and Cook Islands, but feared that they would be found there.

Continuing their quest for a safe haven, on 15 January 1790 they rediscovered Pitcairn Island, which had been misplaced on the Royal Navy's charts. After the decision was made to settle on Pitcairn, livestock and other provisions were removed from Bounty. To prevent the ship's detection, and anyone's possible escape, the ship was burned on 23 January 1790 in what is now called Bounty Bay.

The mutineers remained undetected on Pitcairn until February 1808, when sole remaining mutineer John Adams and the surviving Tahitian women and their children were discovered by the Boston sealer Topaz, commanded by Captain Mayhew Folger of Nantucket, Massachusetts.[13] Adams gave to Folger the Bounty's azimuth compass and marine chronometer.

Seventeen years later, in 1825, HMS Blossom, on a voyage of exploration under Captain Frederick William Beechey, arrived on Christmas Day off Pitcairn and spent 19 days there. Beechey later recorded this in his 1831 published account of the voyage, as did one of his crew, John Bechervaise, in his 1839 Thirty-Six Years of a Seafaring Life by an Old Quarter Master. Beechey wrote a detailed account of the mutiny as recounted to him by the last survivor, Adams. Bechervaise, who described the life of the islanders, says he found the remains of Bounty and took some pieces of wood from it which were turned into souvenirs such as snuff boxes.

Mission details

The details of the voyage of Bounty are very well documented, largely due to the effort of Bligh to maintain an accurate log before, during, and after the actual mutiny. Bounty's crew list is also well chronicled.

Bligh's original log remained intact throughout his ordeal and was used as a major piece of evidence in his own trial for the loss of Bounty, as well as the subsequent trial of captured mutineers. The original log is presently maintained at the State Library of New South Wales, with available transcripts in both print and electronic format.

Mission log

- 1787

- 16 August: William Bligh is ordered to command a breadfruit gathering expedition to Tahiti

- 3 September: Bounty launched from the drydock at Deptford

- 4–9 October: Bounty navigated with a partial crew to an ammunition loading station, south of Deptford

- 10–12 October: Onload of arms and weapons at Long Reach

- 15 October – 4 November: Navigated to Spithead for final crew and stores onload

- 29 November: Made anchor at St Helens, Isle of Wight

- 23 December: Departed English waters for Tahiti

- 1788

- 5–10 January: Anchored off Tenerife, Canary Islands

- 5 February: Crossed equator at 21.50 degrees West

- 26 February: Marked at 100 leagues from the eastern coast of Brazil

- 23 March: Arrived Tierra del Fuego

- 9 April: Entered the Strait of Magellan

- 25 April: Abandoned attempt to round Cape Horn and turned east

- 22 May: Within sight of the Cape of Good Hope

- 24 May – 29 June: Anchored at Simon's Bay

- 28 July: Within sight of Saint Paul's Island, west of Van Diemen's Land

- 20 August – 2 September: Anchored Van Diemen's Land

- 19 September: Past the southern tip of New Zealand

- 26 October: Arrived Tahiti

- 25 December: Shifted mooring to "Toahroah" harbour, Pare "Oparre", Tahiti. Bounty ran aground.[14]

- 1789

- 4 April: Weighed anchor from the harbour at Pare, Tahiti[14]

- 23–25 April: Anchored for provisions off Annamooka (Tonga)

- 26 April: Departed Annamooka for the West Indies

- 28 April: Mutiny – Captain Bligh and loyal crew members set adrift in Bounty's launch

- From this point, Bligh's mission log reflects the voyage of the Bounty launch towards the Dutch East Indies

- 29 April: Bounty launch arrives at Tofua

- 2 May: Bounty launch castaways flee Tofua after being attacked by natives

- 28 May: Landfall on a small island north of New Hebrides. Named "Restoration Island" by Captain Bligh

- 30–31 May: Bounty launch transits to a second nearby island, named "Sunday Island"

- 1–2 June: Bounty launch transits 42 miles to a third island, named "Turtle Island"

- 3 June: Bounty launch sails into the open ocean towards Australia

- 13 June: Bounty launch lands at Timor

- 14 June: Launch castaways circle Timor and land at Coupang. Mutiny is reported to Dutch authorities

- Bligh's mission log from this point reflects his return to England onboard various merchant vessels and sailing ships

- 20 August – 10 September: Sailed via schooner to Pasuruan, Java

- 11–12 September: In transit to Surabaya

- 15–17 September: In transit to the town of Crissey, Madura Strait

- 18–22 September: In transit to Semarang

- 26 September – 1 October: In transit to Batavia (Jakarta)

- 16 October: Sailed for Europe on board the Dutch packet SS Vlydte

- 16 December: Arrived Cape of Good Hope

- 1790

- 13 January: Sailed from Cape of Good Hope for England

- 13 March: Arrived Portsmouth Harbour

Crew list

.jpg.webp)

In the immediate wake of the mutiny, all but four of the loyal crew joined Bligh in the long boat for the voyage to Timor, and eventually made it safely back to England, unless otherwise noted in the table below. Four were detained against their will on Bounty for their needed skills and for lack of space on the long boat. The mutineers first returned to Tahiti, where most of the survivors were later captured by Pandora and taken to England for trial. Nine mutineers continued their flight from the law and eventually settled on Pitcairn Island, where all but one died before their fate became known to the outside world.

| Commissioned officer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | William Bligh | Commanding Lieutenant | Also Acting Purser;[15] died in London on 6 December 1817 | |

| Wardroom officers | ||||

| Loyal | John Fryer | Sailing master | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; died at Wells-next-the-Sea, Norfolk on 26 May 1817 | |

| Mutinied | Fletcher Christian | Acting Lieutenant | To Pitcairn; killed 20 September 1793 | |

| Loyal | William Elphinstone | Master's mate | Went with Bligh; died in Batavia October 1789 | |

| — | Thomas Huggan | Surgeon | Died in Tahiti 9 December 1788, before mutiny | |

| Cockpit officers | ||||

| Loyal | John Hallett | Midshipman | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; died 1794 of illness | |

| Loyal | Thomas Hayward | Midshipman | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; died 1798 in shipwreck | |

| Loyal | Thomas Ledward | Surgeon's mate/Surgeon | Went with Bligh; died in 1789 shipwreck[16] | |

| Loyal | John Samuel | Clerk | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; became Purser [Paymaster] Royal Navy. Died unknown date prior to 1825.[17] | |

| Warrant officers | ||||

| Loyal | William Cole | Boatswain | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; died Royal Navy Hospital March 1833 | |

| Mutinied | Charles Churchill | Master-at-arms | To Tahiti; murdered by Matthew Thompson in Tahiti April 1790 prior to trial | |

| Loyal | William Peckover | Gunner | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; last served in Navy in 1801; died Colchester Essex 16 May 1819, aged 71 | |

| Loyal | Joseph Coleman | Armourer | Detained on Bounty against his will; to Tahiti; tried and acquitted. In 1792 was in Greenwich Naval hospital; last record: discharged from HMS Director to Yarmouth Hospital ship November 1796 | |

| Loyal | Peter Linkletter | Quartermaster | Went with Bligh; died in Batavia October 1789 | |

| Loyal | John Norton | Quartermaster | Went with Bligh; killed by natives in Tofua 2 May 1789 | |

| Loyal | Lawrence LeBogue | Sailmaker | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; joined Bligh on the second breadfruit expedition; died 1795 in Plymouth while serving on HMS Jason | |

| Mutinied | Henry Hillbrandt | Cooper | To Tahiti; drowned in irons during wreck of Pandora 29 August 1791 | |

| Loyal | William Purcell | Carpenter | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; died Haslar Hospital 10 March 1834[18] | |

| Loyal | David Nelson | Botanist (civilian) | Went with Bligh; died 20 July 1789 at Coupang | |

| Midshipmen mustered as Able Seamen | ||||

| Loyal – Likely mutineer | Peter Heywood | Midshipman | Detained on Bounty; to Tahiti; sentenced to death, but pardoned; rose to rank of post-captain and died 10 February 1831 | |

| Loyal | George Stewart | Midshipman | Detained on Bounty; to Tahiti; killed after being hit by gangway at wreck of Pandora 29 August 1791 | |

| Loyal | Robert Tinkler | Midshipman | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; rose to the rank of captain, Royal Navy and died 11 September 1820 age 46 in Norwich, England[19] | |

| Mutinied | Ned Young | Midshipman | To Pitcairn; died 25 December 1800 | |

| Petty Officers | ||||

| Loyal | James Morrison | Boatswain's mate | Stayed on Bounty; to Tahiti; sentenced to death, but pardoned; lost on HMS Blenheim in 1807 | |

| Loyal | George Simpson | Quartermaster's mate | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; died unknown date prior to 1825[17] | |

| Mutinied | John Williams | Armourer's mate | To Pitcairn; killed 20 September 1793 | |

| Loyal | Thomas McIntosh | Carpenter's mate | Detained on Bounty; to Tahiti; tried and acquitted; reported to have gone into Merchant Navy service. | |

| Loyal | Charles Norman | Carpenter's mate | Detained on Bounty; to Tahiti; tried and acquitted; died December 1793[20] | |

| Mutinied | John Mills | Gunner's mate | To Pitcairn; killed 20 September 1793 | |

| Mutinied | William Muspratt | Tailor | To Tahiti; sentenced to death, but released on appeal and pardoned; died on HMS Bellerophon in 1797 | |

| Loyal | John Smith | Steward/Servant | Went with Bligh; arrived safely in England; joined Bligh on the second breadfruit expedition; died unknown date prior to 1825[17] | |

| Loyal | Thomas Hall | Cook | Went with Bligh; died from a tropical disease in Batavia on 11 October 1789 | |

| Mutinied | Richard Skinner | Barber | To Tahiti; drowned in irons during wreck of Pandora 29 August 1791 | |

| Mutinied | William Brown | Botanist's assistant | To Pitcairn; killed 20 September 1793 | |

| Loyal | Robert Lamb | Butcher | Went with Bligh; died at sea en route Batavia to Cape Town | |

| Able Seamen | ||||

| Mutinied | John Adams | Able Seaman | To Pitcairn; pardoned 1825, died 1829; aka Alexander Smith | |

| Mutinied | Thomas Burkitt | Able Seaman | To Tahiti; condemned and hanged 29 October 1792 at Spithead | |

| Loyal | Michael Byrne | Able Seaman | Detained on Bounty; to Tahiti; tried and acquitted | |

| Mutinied | Thomas Ellison | Able Seaman | To Tahiti; condemned and hanged 29 October 1792 at Spithead | |

| Mutinied | Isaac Martin | Able Seaman | To Pitcairn; killed 20 September 1793 | |

| Mutinied | William McCoy | Able Seaman | To Pitcairn; committed suicide c. 1799 | |

| Mutinied | John Millward | Able Seaman | To Tahiti; condemned and hanged 29 October 1792 at Spithead | |

| Mutinied | Matthew Quintal | Able Seaman | To Pitcairn; killed 1799 by Adams and Young | |

| Mutinied | John Sumner | Able Seaman | To Tahiti; drowned in irons during wreck of Pandora 29 August 1791 | |

| Mutinied | Matthew Thompson | Able Seaman | To Tahiti; killed by Tahitians in April 1790 after killing Charles Churchill prior to trial | |

| — | James Valentine | Able Seaman | Died of scurvy at sea 9 October 1788 prior to mutiny; listed in some texts as an Ordinary Seaman | |

Discovery of the wreck

Luis Marden rediscovered[21] the remains of Bounty in January 1957. After spotting remains of the rudder[22] (which had been found in 1933 by Parkin Christian, and is still displayed in the Fiji Museum in Suva), he persuaded his editors and writers to let him dive off Pitcairn Island, where the rudder had been found. Despite the warnings of one islander – "Man, you gwen be dead as a hatchet!"[23] – Marden dived for several days in the dangerous swells near the island, and found the remains of the ship: a rudder pin, nails, a ships boat oarlock, fittings and a Bounty anchor that he raised.[22][27] He subsequently met with Marlon Brando to counsel him on his role as Fletcher Christian in the 1962 film Mutiny on the Bounty. Later in life, Marden wore cuff links made of nails from Bounty. Marden also dived on the wreck of Pandora and left a Bounty nail with Pandora.

Some of the Bounty's remains, such as the ballast stones, are still partially visible in the waters of Bounty Bay.

The last of Bounty's four 4-pounder cannon was recovered in 1998 by an archaeological team from James Cook University and was sent to the Queensland Museum in Townsville to be stabilised through lengthy conservation treatment via electrolysis over a period of nearly 40 months. The gun was subsequently returned to Pitcairn Island, where it has been placed on display in a new community hall. Several other pieces of the ship were found but local law forbids removal of such items from the island.[28]

Modern reconstructions

When the 1935 film Mutiny on the Bounty was made, sailing vessels (often with assisting engines) were still common; existing vessels were adapted to act as Bounty and Pandora. For Bounty, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) had the wooden 19th century schooner Lily[29] transformed into the three masted full square-rigged Bounty. Metha Nelson, which had been featured in movies from 1931 on, was given the role of Pandora.[30] Both reconstructions, the modern Bounty and Pandora, sailed from the US west coast to Tahiti for film shoots at the original location. A model ship was built in two parts to serve as a set design in an MGM studio.

For the 1962 film, a new Bounty was constructed in 1960 in Nova Scotia. For much of 1962 to 2012, she was owned by a not-for-profit organisation whose primary aim was to sail her and other square rigged sailing ships, and she sailed the world to appear at harbours for inspections, and take paying passengers, to recoup running costs. For long voyages, she took on volunteer crew.

On 29 October 2012, sixteen Bounty crew members abandoned ship off the coast of North Carolina after getting caught in the high seas brought on by Hurricane Sandy.[31] The ship sank, according to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, at 12:45 UTC Monday 29 October 2012 and two crew members, including Captain Robin Walbridge, were reported as missing. The captain was not found and presumed dead on 2 November 2012.[32] It was later reported that the Coast Guard had recovered one of the missing crew members, Claudene Christian, descendant of Fletcher Christian of the original Bounty.[33][34] Christian was found to be unresponsive and pronounced dead on arrival at a hospital in North Carolina.[35][36]

A second Bounty replica, named HMAV Bounty, was built in New Zealand in 1979 and used in the 1984 film The Bounty. The hull is constructed of welded steel oversheathed with timber. For many years she served the tourist excursion market from Darling Harbour, Sydney, Australia and appeared in a Tamil language Indian (1996 film), before being sold to HKR International Limited in October 2007. She was then a tourist attraction (also used for charter, excursions and sail training) based in Discovery Bay, on Lantau Island in Hong Kong, and was given an additional Chinese name 濟民號.[37] She was decommissioned on 1 August 2017.[38] The company has not disclosed the ship's fate.

References

- ↑ Knight, C. (1936). Carr Laughton, Leonard George; Anderson, Roger Charles; Perrin, William Gordon (eds.). "HM Armed Vessel Bounty". The Mariner's Mirror. Society for Nautical Research. 22 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1080/00253359.1936.10657185. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ↑ Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.

- ↑ "Cannon from HMAS Bounty". Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Erskine, Nigel (May–June 1999). "Reclaiming the Bounty". Archaeology. 52 (3). Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ See picture of cannon at;[3] for the disposition of the four ship's cannons see.[4]

- ↑ Muhammad, Khalil Gibran (14 August 2019). "The Barbaric History of Sugar in America". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Human Cost".

- ↑ McKinney, Sam (1999) [1989]. Bligh!: The Whole Story of the Mutiny Aboard H.M.S. Bounty. Victoria, British Columbia: TouchWood Editions=. ISBN 978-0-920663-64-6.

- ↑ McKinney, Sam (1999) [1989]. Bligh!: The Whole Story of the Mutiny Aboard H.M.S. Bounty. Victoria, British Columbia: TouchWood Editions=. ISBN 978-0-920663-64-6.

- ↑ Alexander, C. (2003). The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-653246-2.

- ↑ Alexander 2003, p. 48.

- ↑ McKinney, Sam (1999) [1989]. Bligh!: The Whole Story of the Mutiny Aboard H.M.S. Bounty. Victoria, British Columbia: TouchWood Editions=. ISBN 978-0-920663-64-6.

- ↑ Young, Rosalind Amelia (1894). "An transcription of Floger Log entry Concerning the Bounty and Pitcairn Island pp.36–40". Archived from the original on 4 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- 1 2 Bligh, William (2012). Galloway, James (ed.). Bounty Logbook (Kindle ed.). Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ↑ "Bounty's Crew Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ↑ "HMAS Bounty Crew biographies". Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Marshall, John (1825). "Royal Naval Biography pub 1825 p.762". Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ↑ The True Story of Mutiny on the Bounty p.182

- ↑ The Scots Magazine Archived 28 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine Volume 86, 1820

- ↑ ""Bounty's Company"". Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ "Pitcairn Miscellany". Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- 1 2 "The 'Bounty's' Last Relics". Life. Vol. 44, no. 6. 10 February 1958. pp. 38–41. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Jenkins, Mark (3 March 2003). "National Geographic Icon Luis Marden Dies". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ↑ "Bounty anchor at the town square". Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Marden, Luis (December 1957). "I Found the Bones of the Bounty". National Geographic.

- ↑ "HMS Pandora Encyclopedia". Pitcairn Islands Study Center. Pacific Union College. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ For a recent picture of anchor see;[24] Two Bounty anchors was lost off Tubai by the mutineers; one was seen in 1957;[25] the other was recovered by Pandora.[26]

- ↑ "Reclaiming the Bounty". Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ↑ "The Lily, H.M.S Bounty.". Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) from winthrop.dk. access-date May 14, 2023. - ↑ "SECOND BOUNTY LAUNCHED HERE British Consul, Movie Star Participate; Craft Soon to Visit South Seas". San Pedro News Pilot, Volume 7, Number 140. San Pedro, Los Angeles. 15 August 1934. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

About 300 persons witnessed yesterday's re-launched of a "Bounty". Subsequently, about 100 guests of the moving picture company were entertained at a buffet meal aboard the Pandora [...] Formerly the Metha Nelson, the Pandora was reconditioned at Craig shipyard, Long Beach, originally for the filming of "Treasure Island."

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy: Hurricane Sandy sinks tall ship HMS Bounty". CBS News. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Grier, Peter (29 October 2012). "The story behind the HMS Bounty, sunk by Sandy off N.C. coast". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Jonsson, Patrik (30 October 2012). "HMS Bounty casualty claimed tie to mutinous Fletcher Christian". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Allen, Nick (31 October 2012). "Sandy's Bounty victim was descendent of man who led famous mutiny". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Dolak, Kevin; Effron, Lauren (30 October 2012). "Woman Dies After Hurricane Sandy Ship Rescue". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Dalesio, Emery P.; Lush, Tamara (31 October 2012). "HMS Bounty: Search for missing captain continues". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ "The Bounty" (PDF). 24 October 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ "The Bounty web site". www.thebounty.hk. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

External links

- Photo gallery of HMS Bounty replica at Tall Ships Nova Scotia 2009 and 2012. Archived 22 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine