Thomas Davies | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1737 Shooter's Hill (London), England |

| Died | 16 March 1812 (aged 74–75) Blackheath (London), England |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Royal Artillery |

| Rank | Lieutenant-general |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

Thomas Davies FRS FLS (c. 1737 – 16 March 1812) was a British Army officer, artist, and naturalist.

He was born c. 1737 in Shooter's Hill (London), England and died 16 March 1812 in Blackheath (London). He rose to the rank of Lieutenant-general in the Royal Artillery. He studied drawing and recorded military operations in water-colours during several military campaigns in North America. He later became a noted artist and naturalist. He was the first to illustrate and describe the superb lyrebird.

His work was not well known until after a 1953 auction from the Earl of Derby's library.[1][2] His paintings were later shown as part of a major exhibition, 2 July – 4 September 1972, at the National Gallery of Canada.[3]

Early life

Very little is known of his early life. In his will, he lists his father as David Davies from Shooter's Hill.[4]

Military service

Davies began military service at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich in 1755. There he received training in topographic drawing to provide detailed and accurate drawings for military use. By 1757 he became second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery and began service abroad in Canada.[5]

French and Indian War

His earliest work is a drawing of Halifax during the failed Louisbourg expedition in 1757. The next year, he recorded the military operations during the Siege of Louisbourg, including the Expulsion of the Acadians.[5]

Starting in 1759, he was with General Jeffery Amherst's forces, first at the Fort Ticonderoga and then at Fort Crown Point. In 1760, he fought in the attack against Montreal and commanded a boat in a naval battle, which he also illustrated.[5]

Davies's 1760 painting A View of Fort La Galette, Indian Castle, and Taking a French Ship of War on the River St. Lawrence, by Four Boats of One Gun Each of the Royal Artillery Commanded by Captain Streachy contains a large amount of documentary information—not only about the fort, but also the river battle and the clothing worn by Indigenous observers. In 1755, 3,000 Haudenosaunee lived at Fort La Galette.[6]

After the attack against Montreal, he surveyed the regions surrounding Lake Ontario for several years, producing both military maps and artistic landscapes.[7] He painted a series of waterfalls, including views of Great Seneca Falls and Niagara Falls. His 1762 watercolour of Niagara Falls, An East View of the Great Cataract of Niagara, was the first eyewitness painting and the first accurate view of the falls.[1][8]

American Revolutionary War

In 1776, Davies returned to North America with General William Howe during the American War for Independence.[9] After the Battle of Long Island in August, he illustrated the British fleet in the harbour.[10] Later that year, he continued with General Howe at the Battle of White Plains and the subsequent Battle of Fort Washington, where he illustrated the battle scene.[11]

Under the command of General Charles Cornwallis at the Battle of Fort Lee, Davies captured the landing at and ascent of the Palisades by the British forces. This work has sometimes been attributed to Lord Francis Rawdon, since he later bought it from Davies.[12]

In 1777, he was sent to command Fort Knyphausen, previously known as Fort Washington. In 1780, he returned to England.[13]

- Battle Illustrations

A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel Redouts near New York on the 16 of November 1776 by the British and Hessian Brigades

A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel Redouts near New York on the 16 of November 1776 by the British and Hessian Brigades The Landing of the British Forces in the Jerseys on the 20th of November 1776 under the command of the Rt. Hon. Lieut. Gen. Earl Cornwallis

The Landing of the British Forces in the Jerseys on the 20th of November 1776 under the command of the Rt. Hon. Lieut. Gen. Earl Cornwallis

Royal Artillery command

After the war, he received several promotions and was assigned to command posts in Gibraltar, the West Indies, and Canada. In 1799, he was appointed colonel commandant of the Royal Artillery. His last promotion was to the rank of lieutenant-general in 1803.[13]

Artist and naturalist

In 1781, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society.[14] He was also a fellow of the Linnean Society of London[15] and contributed several articles, especially regarding ornithology in Australia.[5] In 1800, he was the first to illustrate and describe the superb lyrebird, in the Transactions of the Linnean Society of London.[16][17][18] He also read reports to the society on the southern emu-wren of Australia and the meadow jumping mouse of Canada.[19]

Style

Davies' style combines the precision of military artists with the skills of naturalists. His works have been compared to those of Henri Rousseau, George Edwards, and Paul Sandby.[20]

Publications

- Davies, Thomas (6 June 1797). . Transactions of the Linnean Society. Vol. 4. London (published 1798). pp. 155–7.

- Davies, Thomas (6 February 1798). . Transactions of the Linnean Society. Vol. 4. London (published 1798). pp. 240–2.

- Davies, Thomas (4 November 1800). . Transactions of the Linnean Society. Vol. 6. London (published 1802). pp. 207–10.

Gallery

A View of Halifax in Nova Scotia, earliest dated painting (1757)

A View of Halifax in Nova Scotia, earliest dated painting (1757) A View of the Plundering and Burning of the City of Grimross, forcing the expulsion of the Acadians (1758)

A View of the Plundering and Burning of the City of Grimross, forcing the expulsion of the Acadians (1758).jpg.webp) St. John River Campaign: The Construction of Fort Frederick (1758)

St. John River Campaign: The Construction of Fort Frederick (1758) A View of Fort La Galette, Indian Castle, and Taking a French Ship of War on the River St. Lawrence, by Four Boats of One Gun Each of the Royal Artillery Commanded by Captain Streachy, one boat commanded by Thomas Davies (1760)

A View of Fort La Galette, Indian Castle, and Taking a French Ship of War on the River St. Lawrence, by Four Boats of One Gun Each of the Royal Artillery Commanded by Captain Streachy, one boat commanded by Thomas Davies (1760)

A View of the Casconchiagon or Great Seneca Falls, Lake Ontario, taken 1766

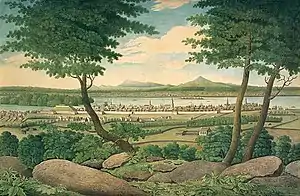

A View of the Casconchiagon or Great Seneca Falls, Lake Ontario, taken 1766 Montreal, last work, panorama of Montreal (1812)

Montreal, last work, panorama of Montreal (1812)

References

- 1 2 "Captain Thomas Davies (1737–1812): An East View of the Great Cataract of Niagara". Christie's. 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Hubbard (1972), pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Hubbard (1972), p. 4.

- ↑ Hubbard (1972), p. 46.

- 1 2 3 4 Hubbard, R. H. (1983). "Davies, Thomas". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 5. University of Toronto.

- ↑ Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- ↑ Tovell, Rosemarie L. "Thomas Davies". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Dickenson (1998), p. 195.

- ↑ Murdoch (1894), p. 37.

- ↑ Davies, Thomas (1776). The British fleet in New York Harbor just after the Battle of Long Island.

- ↑ Davies, Thomas (1776). A view of the attack against Fort Washington.

- ↑ Lefkowitz (1998), Notes to illustration 6–7, after p. 100.

- 1 2 Murdoch (1894), p. 38.

- ↑ Dickenson (1998), p. 198.

- ↑ List of the Linnean Society of London. London. 1805.

- ↑ Olsen (2001), p. 42.

- ↑ Olsen (2010), p. 178.

- ↑ Chisholm (1911), p. 179.

- ↑ Dickenson (1998), pp. 199.

- ↑ Dickenson (1998), pp. 198–9.

Bibliography

- Brandon, Laura. War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2021. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 179.

- Dickenson, Victoria (1998). Drawn from Life: Science and Art in the Portrayal of the New World. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-08020-8073-8.

- Hubbard, R. H. (1972). Thomas Davies, c. 1737–1812. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada.

- Lefkowitz, Arthur S. (1998). The Long Retreat: The Calamitous American Defense of New Jersey, 1776. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-08135-2759-8.

- Murdoch, R. H. (1894). "The Brome-Walton Family". Minutes of Proceedings. Woolwich, London: Royal Artillery Institution.

- Olsen, Penny (2001). Feathers and brush: three centuries of Australian bird art. ISBN 0-643-06547-4.

- Olsen, Penny (2010). Upside down world: early European impressions of Australia's curious animals. National Library of Australia. ISBN 978-06422-7706-0.

External links

- War Art in Canada: A Critical History, by Laura Brandon published by the Art Canada Institute.

- "Thomas Davies". National Gallery of Canada.

- "Thomas Davies". Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- "Thomas Davies". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013.