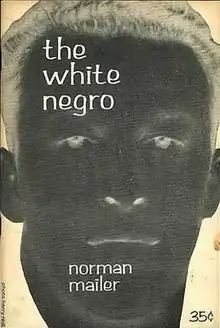

(publ. City Lights) | |

| Author | Norman Mailer |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Essay |

| Publisher | City Lights |

Publication date | 1957 |

| Media type | |

The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster is a 9,000-word essay by Norman Mailer that connects the "psychic havoc" wrought by the Holocaust and atomic bomb to the aftermath of slavery in America in the figuration of the Hipster, or the "white negro".[1] The essay is a call to abandon Eisenhower liberalism and a numbing culture of conformity and psychoanalysis in favor of the rebelliousness, personal violence and emancipating sexuality that Mailer associates with marginalized black culture.[2] The White Negro was first published in the 1957 special issue of Dissent, before being published separately by City Lights.[3] Mailer's essay was controversial upon its release and received a mixed reception, winning praise, for example, from Eldridge Cleaver and criticism from James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, and Allen Ginsberg. Baldwin, in particular, heavily criticized the work, asserting that it perpetuated the notorious "myth of the sexuality of Negros" and stating that it was beneath Mailer's talents.[4] The work remains his most famous and most reprinted essay[5] and it established Mailer's reputation as a "philosopher of hip".[6][7]

Background

The origins of The White Negro (WN) date from the mid-1950s. According to the biography of Carl Rollyson, Mailer wanted to tap into the energy of the Beat Generation and the changes of consciousness members such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac inspired.[8] Mailer used "Quickly: A Column for Slow Readers", his column in The Village Voice, to develop and explore his philosophy of "Hip", or "American existentialism".[9] In the psychopathic character Marion Faye from his 1955 novel The Deer Park Mailer considered he had created a prototypical Hipster.[10][11] Mailer also tapped into the contemporary cultural dialogue about black male sexuality and, with the prompting of Lyle Stuart, published four paragraphs about black male super-sexuality in the Independent.[12] Mailer's outrageous sentiment was not well received (notable critics included William Faulkner, Eleanor Roosevelt, and W. E. B. Du Bois) but the debate prompted him to begin work on WN.[13][14]

Lipton's Journal, Mailer's unpublished 105,000-word diary of self-analysis (written over four months while experimenting with marijuana), also contributed to the essay's genesis.[15] The journal documents "his insights [that] challenge some of the dominant ideas of Western thought", specifically the dualisms that Mailer saw within every individual, like that of the saint and the psychopath.[16] Mailer had planned to use the insights from Lipton's Journal in a series of novels which he ultimately never wrote, but he did incorporate some ideas from the journal into WN.[7] Mailer summarizes these ideas in one of the journal's last entries:

Generally speaking we have come to the point in history—in this country anyway—where the middle class and upper middle class is composed primarily of the neurotic-conformists, and the saint-psychos are found in some of the activities of the working class (as opposed to the working class itself), in the Negro people, in Bohemians, in the illiterates, among the reactionaries, a few of the radicals, some of the prison population, and of course in the mass communication media.[14]

Other influences on both Lipton's Journal and The White Negro include the psycho-sexual theories of Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Reich, the writings of Karl Marx, and the music of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie and other bebop jazz artists.[17] Dearborn writes that Mailer saw these great men of jazz as quintessential figures of Hip: Miles Davis, for example, "was the avatar of Hip, and, with his lean, chiseled good looks and his ultra cool manner he was distinctly a sex symbol as well, appealing to white women as well as black".[18] These elements provided the background for Mailer's new-found understanding of social reality.[19]

Synopsis

The White Negro is a 9,000-word essay divided into six sections of varying lengths.[20]

In Section 1, Mailer argues that the twin horrors of the atom bomb and the concentration camps have wrought "psychic havoc" by subjecting individual human lives to the calculus of the state machine. The collective practices of Western progress seem to render life and death meaningless for the individual who is compelled to join the numbed masses in a "collective failure of nerve".[21] Courage only seems to be present in marginalized, isolated people who can stand in opposition to these practices.[22]

The hipster had absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro, and for practical purposes could be considered a white Negro.

—§2, p. 341

Section 2 proposes that the marginalized figure — "the American existentialist" — lives with the knowledge of quick death, the possibility of state violence, the compulsory need to conform, and the sublimation of baser desires. He knows that the only answer is to accept these conditions, divorce himself from the bored sickness of society, and seek the "rebellious imperatives of the self". Mailer presents a dichotomy: one path leads to a quiet prison of the mind and body, that is, to boredom, sickness, and desperation, while the other leads to "new kinds of victories [that] increase one's power for new kinds of perception". Either one is a rebel — the Hip, the psychopath — or, tempted by the promise of success, one conforms to "the totalitarian tissues of an American society", and becomes Square.[22] Because he has lived on the margins of society, for Mailer the American Negro is the model for the Hipster: someone living for the primitive present and the pleasures of the body.[23] Mailer links this proposition with jazz and its appeal to the sensual, the improvisational, and the immediate, in other words, to what Mailer calls the "burning consciousness of the present" felt by the existentialist, the bullfighter, and the Hipster alike.[24] In summary, one can "remain in life only by engaging death".[25]

For Hip is the sophistication of the wise primitive in a giant jungle, and so its appeal is still beyond the civilized man.

—§3, p. 343

Section 3 defines the Hipster further as a "philosophical psychopath" interested in codifying, like Hemingway,[26] the "dangerous imperatives" that define his experience. He is a contradiction, possessing a "narcissistic detachment" from his own "unreasoning drive" allowing him to shift his attention from immediate gratification to "future power".[27] Psychopaths, Mailer continues, "are trying to create a new nervous system for themselves" one that distinguishes itself from the "inefficient and often antiquated nervous circuits of the past". Yet the stable middle-class values necessary to achieve this via sublimation "have been virtually destroyed in our time".[28] Psychoanalysis cannot provide the answer sought by the overstretched nervous system. It is a practice which only succeeds in "tranquilizing" a patient's most interesting qualities: "The patient is indeed not so much altered as worn out—less bad, less good, less bright, less willful, less destructive, less creative".[28] The nervous system is remade, Mailer contends, by trying to "live the infantile fantasy", in which the psychopath traces the source of his creation in an atavistic quest to give voice and action to infantile, or forbidden, desires.[29] In this "morality of the bottom", then, the psychopath finds the courage to act free of the "old crippling habit" that has anesthetized him.[30] Now, he can purge his violence, even through murder, but what he really seeks is physical love as a "sexual outlaw" in the form of an orgasm more "apocalyptic than the one which preceded it".[31]

Section 3 ends with an introduction to the language of Hip, a "special language" that "cannot be taught" because it is based on a shared experience of "elation and exhaustion" and the dynamic movements of man as a "vector in a network of forces" rather than "as a static character in a crystalized field".[32]

Section 4 develops this language further, linking the language to movement and the search for the "unachievable whisper of mystery within the sex, the paradise of limitless energy and perception just beyond the next wave of the next orgasm."[33]

Truth is no more nor less than what one feels at each instant in the perpetual climax of the present.

—§5, p. 354

Section 5 posits that the Hip judgement of character is "perpetually ambivalent and dynamic".[34] Mailer suggests, developing the existential reality of the Hipster further, that men are character as well as context, giving way to "an absolute relativity where there are no truths other than the isolated truths of what each observer feels at each instant of his existence".[35] The consequence of this realization is liberation from the "Super-Ego of society". The moral imperative, then, centers in the individual who acts in accordance with his desires, not as the group would have him behave: "The nihilism of Hip proposes as its final tendency that every social restraint and category be removed, and the affirmation implicit in the proposal is that man would then prove to be more creative than murderous and so would not destroy himself".[35] The idea is that even individual acts of violence — because they come from courage to act — prove more desirable than any collective state violence, as the former would be more genuine, creative, and cathartic.[36] A "psychically armed rebellion", Mailer continues, is necessary to free everyone: "A time of violence, new hysteria, confusion and rebellion will then be likely to replace the time of conformity".[37] This potentially violent rebellion would be preferable to the "murderous liquidations of the totalitarian state".[38]

Finally, in Section 6, Mailer speculates whether "the last war of them all" will be between factions of socially polar communities or through despair at the current crisis of capitalism. Perhaps, Mailer ends, we still have something to learn from Marx.[39]

Analysis

True to his thesis in "First Advertisement for Myself" (from his 1959 collection of essays), Mailer can be seen to be attempting "a revolution in the consciousness of our time" by challenging the thoughts and practices that sanitized American life after World War II.[40] In his biography on Mailer, J. Michael Lennon suggests that The White Negro was Mailer's attempt to "will into being an army of hipster revolutionaries who could bring about an urban utopia".[41] In a response to Jean Malaquais, who had criticized WN in the magazine Dissent, Mailer wrote: "the removal therefore of all social restraints while it would open us to an era of incomparable individual violence would still spare us the collective violence of rational totalitarian liquidations . . . and would — and here is the difference — by expending the violence directly, open the possibility of working with that human creativity which is violence's opposite".[42] While WN embraces violence, it makes a distinction between violence by the state and individual violence: the former leads to concentration camps and pogroms, while the latter can lead to freedom.[43] For Mailer, writes Maggie McKinley, violence seems to be an essential part of the masculinity of the Hipster, helping to oppose collectivizing and numbing social forces.[44] In a 1957 letter to a publicly critical Malaquais, Mailer clarified his beliefs that: (1) barbarism could be an alternative to totalitarianism, and (2) that human energy should not be sublimated at the expense of the individual.[45]

Both Jean Malaquais and Ned Polsky accused Mailer of romanticizing violence, and Laura Adams highlighted the consequences of Mailer's testing his "violence as catharsis" theory in real life when he nearly killed his second wife Adele by stabbing her twice with a penknife.[46] Polsky stated that Mailer was well aware of the drawbacks in the life of a hipster, but because of his fascination with them, Mailer romanticized away the consequences. For Polsky the hipster wasn't as sexually liberated as Mailer tried to make him seem: "Mailer confuses the life of action with the life of acting out".[47] Because the hipster is crippled psychologically, he is also crippled sexually. Polsky dismissed Mailer's hipster and upheld psychoanalysis as a greater benefit to sexual health.[47]

Although The White Negro takes as its subject a subcultural phenomenon, it represents a localized synthesis of Marx and Freud, and thus presages the New Left movement and the birth of the counterculture in the United States. Rollyson suggests that Mailer dismissed a Freudian approach to psychology that called for the adjustment of the individual to societal norms and instead espoused Wilhem Reich's emphasis on sexual energy and orgasm.[8] Christopher Brookeman created a possible motivation for Mailer through his idea of Marxism combined with a kind of "Reichian Freudianism" to find solutions "in the better orgasm" which in turn would allow for the rise of one's "full instinctual potential".[48] Reich inspired Mailer as one of the few intellectuals or writers in general who had deeply explored the power, primacy and potential of the male orgasm. The White Negro is explicitly influenced by Reich in two primary ways: the exaltation of male sexual eruption and the related theme of the virile, iconoclastic male hipster casting off societal rules and impositions to be led instead by his sex, his body and his instincts. These provide a balm and shield against all physical and mental ailments and diseases, including cancer.[49] Mailer makes a comparison of the hipster hero with other outliers in society such as the Negro, the lover and the psychopath.[50] He commends the social outliers' ability to live in a "burning" present, one with a continuous awareness of their closeness to death.[50] Likewise, Mailer's admiration for Linder's description of the psychopath in Rebel without a Cause: The Hypnoanalysis of the Criminal Psychopath influenced his formulation of the drama of psychopath as being "one that, in the end, centers on his quest for love".[51] This quest for love — or "the search for an orgasm more apocalyptic than the one which preceded it" — allows the psychopath to become "an embodiment of the extreme contradictions of society which formed his character".[51]

Mailer presents a theme of dualistic "opposed extremes" in his characterization of the hipster and the square.[52] Tony Tanner believes that Mailer was excited by the twentieth century's "tendency to reduce all of life to its ultimate alternatives", noting the value that Mailer places on opposite couplings.[53] The White Negro demonstrates Mailer's fondness for duality when he ponders if "the last war of them all will be between the blacks and the whites, or between the women and the men, or between the beautiful and the ugly", again listing some of his favorite alternatives.[38] Similarly, Ihab Hassan shows this duality by using the hipster's face as that of an "alienated" hero covered by a twisted mask in order to hide the look of disgust towards one's own experiences and encounters while out in "search of kicks".[54]

Tracy Dahlby argues that Mailer's hipster is still a necessity in the fight against conformity by consumption.[55] According to Mailer, this fight against conformity will liberate the "squares".[56] Focusing on a post-9/11 world similar to the years after World War II, Dahlby points to the new age of technology, social media, and increased consumption as symptomatic of a mindless society. In a world that exposes people to unspeakable violence and fear through social media, desensitized news coverage, and radical conspiracy theories, the paucity of existential hipsters puts people at risk of failing to achieve a fulfilling life.[57]

Publication

Though the bulk of the content of The White Negro had appeared in piecemeal fashion in Mailer's regular columns in the Village Voice,[9] the essay in its entirety first appeared in a special issue of Dissent in 1957.[58] It triggered a "great orgasm debate" in subsequent issues, touching on the zeitgeist of the fifties and the effects of psychoanalysis in general. Sorin observes that the board of Dissent published the essay apparently without debate, temporarily tripling the periodical's subscriptions.[58] It was only later, relates then-editor Irving Howe, that they realized publishing the essay as-written was "unprincipled".[59] Despite the initial controversy, Lennon notes, WN became the most reprinted essay of an era.[60] It was reprinted with rebuttals from Ned Polsky and Jean Malaquais, followed by Mailer's response, as "Reflections on Hip", in his 1959 miscellany, Advertisements for Myself. The essay and "Reflections on Hip" were reprinted the same year in pamphlet form by City Light Press, and again by this press several times over the next 15 years.[6] Most recently it appears in Mind of an Outlaw (2014).[61] Young enthusiasts of Mailer's essay, states Lennon, carried their copies of the City Light's reprint proudly as a "trumpet of defiance" throughout an awakening nation.[41]

Reception

Reception to The White Negro was mixed, and the essay has been controversial since its publication. It has, according to J. Michael Lennon, been "the most discussed American essay in the quarter century after World War II".[60] According to Tracy Dahlby, Mailer's views were a hot topic in 1957 and many of his critics accused him of accepting violence as a "form of existential expression".[56]

In a letter to Albert Murray, Ralph Ellison called the essay "the same old primitivism crap in a new package".[9] Similarly, Allen Ginsberg termed the essay "very square" and recalled that Jack Kerouac thought Mailer an "intellectual fool". Both considered The White Negro a "macho folly" that could not be reconciled with the "tenderheartedness" of the Beat perspective.[62] Ginsberg saw no Dostoyevskian hero in Mailer's violent Hipster.

Several prominent critics, such as James Baldwin, chided Mailer publicly for their perception that, with The White Negro, he was openly aping lesser writers such as Jack Kerouac in order to jump on the bandwagon of moody, meandering, faux-thrill-seeking Beatniks.[9] Baldwin, in his essay "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy" for Esquire (May 1961) called The White Negro "impenetrable", and wondered how Mailer, a writer that he saw as brilliant and talented, could write an essay that was so beneath him.[4] For Baldwin, Mailer's essay simply perpetuated the "myth of the sexuality of Negros" while attempting to sell white people their own innocence and purity.[63] Baldwin showed great respect for Mailer's talent, but aligned The White Negro with other distractions — like running for mayor of NYC — that Baldwin saw as beneath Mailer and distracted him from his real responsibility as a writer.[64]

Kate Millett's view of The White Negro criticized Mailer of making a virtue of violence. In her book Sexual Politics, she makes the claim that Mailer finds that violence is something that he has fallen in love with as a personal and sexual style.[65] She states that for Mailer, "a rapist is only rapist to a square" and that "rape is a part of life". Millett goes on to criticize Mailer of matching the aesthetic of Hip to harmful masculine pride.[65] Additionally, Millett accuses WN of celebrating and romanticizing stereotypes about Black hyper-sexuality.

Similarly, author and intellectual Lorraine Hansberry joined Baldwin in rejecting the same message. She argued WN also excuses and idealizes society's denigrating and ostracizing Black people to further Mailer's agenda of repackaging White racism as Black iconoclasm.[66] While Mailer seemed to have a sense of the historical importance of the late 1950s, explains Ginsberg, he was being an "apocalyptic goof" with his naive Hipster figuration that Kerouac saw as "well intentioned but poisonous, in the sense that it encouraged an image of violence".[67]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Lennon 2013, p. 77.

- ↑ Greif 2010.

- ↑ Sorin 2005, pp. 144–145, 330.

- 1 2 Baldwin 1988, p. 277.

- ↑ Lennon 1988, p. x.

- 1 2 Lennon & Lennon 2018, p. 29.

- 1 2 Lennon 2013, p. 189.

- 1 2 Rollyson 1991, p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 Menand 2009.

- ↑ Gutman 1975, p. 67.

- ↑ Trilling 1972, p. 56.

- ↑ Dearborn 1999, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Dearborn 1999, p. 127.

- 1 2 Lennon 2013, p. 190.

- ↑ Lennon 2013, pp. 182–88.

- ↑ Lennon 2013, pp. 183, 189.

- ↑ Lennon 2013, pp. 184–88.

- ↑ Dearborn 1999, p. 117.

- ↑ Rollyson 1991, p. 111.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, pp. 337–58.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 338.

- 1 2 Mailer 1959, p. 339.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, pp. 340–341, 348, 356.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, pp. 341–342.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 342.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 340.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 343.

- 1 2 Mailer 1959, p. 345.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 346.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, pp. 348, 347.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 348.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, pp. 350–351.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 353.

- 1 2 Mailer 1959, p. 354.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 355.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 356.

- 1 2 Mailer 1959, p. 357.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 358.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 17.

- 1 2 Lennon 2013, p. 221.

- ↑ Mailer 1959, p. 363.

- ↑ Lennon 2013, p. 219.

- ↑ McKinley 2017, p. 11.

- ↑ Lennon 2014, p. 228.

- ↑ Adams 1976, TR.

- 1 2 Polsky 1959, p. 367.

- ↑ Grimsted 1986, p. 430.

- ↑ Gordon 1980, p. 39-40.

- 1 2 Braun 2015, p. 148.

- 1 2 Braun 2015, p. 150.

- ↑ Tanner 1974, p. 128.

- ↑ Tanner 1974, p. 127.

- ↑ Hassan 1962, p. 5.

- ↑ Dahlby 2011, p. 220.

- 1 2 Dahlby 2011.

- ↑ Dahlby 2011, p. 219.

- 1 2 Sorin 2005, p. 144.

- ↑ Sorin 2005, p. 145.

- 1 2 Lennon 2013, p. 220.

- ↑ Mailer 2014, pp. 41–65.

- ↑ Manso 2008, pp. 258, 259.

- ↑ Baldwin 1988, p. 272, 277.

- ↑ Baldwin 1988, pp. 276, 277, 283.

- 1 2 Millett 2016, p. 444.

- ↑ Millett 2016, p. 327, passim.

- ↑ Manso 2008, p. 260.

Bibliography

- Adams, Laura (1976). Existential Battles: The Growth of Norman Mailer. Athens, OH: Ohio UP. ISBN 978-0821401828.

- Adams, Laura, ed. (1974). Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Stand Up?. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0804690669.

- Baldwin, James (1988). "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy". Collected Essays. New York: Library of America. pp. 269–285. ISBN 978-1883011529.

- Bishop, Sarah (2012). "The Life and Death of the Celebrity Hero in Maidstone". The Mailer Review. 6 (1): 288–308. OCLC 86175502.

- Braun, Heather (Fall 2015). "The Roving Psychopath In Love: 'The White Negro' and Lolita". The Mailer Reviews. 9 (1): 148–155.

- Dahlby, Tracy (2011). "'The White Negro' Revisited: The Demise of the Indispensable Hipster". The Mailer Review. 5 (1): 218–230. OCLC 86175502. Retrieved 2017-09-18.

- Dearborn, Mary V. (1999). Mailer: A Biography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0395736555.

- Ehrlich, Robert (1978). Norman Mailer: The Radical as Hipster. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810811607.

- Gordon, Andrew (1980). An American Dreamer: A Psychoanalytic Study of the Fiction of Norman Mailer. London: Fairleigh Dickinson UP. ISBN 978-0838621585.

- Greif, Mark (October 24, 2010). "What Was the Hipster?". New York. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- Grimsted, David (September 1986). "The Jekyll-Hyde Complex in Studies of American Popular Culture". Reviews in American History. 14 (3): 428–435. doi:10.2307/2702620. JSTOR 2702620.

- Gutman, Stanley T. (1975). Mankind in Barbary: The Individual and Society in the Novels of Norman Mailer. Hanover, NH: The University Press of New England. OCLC 255515793.

- Hassan, Ihab (January 1962). "The Character of Post-War Fiction in America". The English Journal. 51 (1): 428–435. JSTOR 810510.

- Holmes, John Clellon (February 1958). "The Philosophy of the Beat Generation". Esquire. 49 (2): 35–47.

- Lennon, J. Michael, ed. (1988). Conversations with Norman Mailer. Jackson and London: U of Mississippi P. ISBN 978-0878053520.

- — (2013). Norman Mailer: A Double Life. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439150214. OCLC 873006264.

- —; Lennon, Donna Pedro (2018). Lucas, Gerald R. (ed.). Norman Mailer: Works and Days (Revised and Expanded ed.). Atlanta: Norman Mailer Society. ISBN 9781732651906. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- —, ed. (2014). The Selected Letters of Norman Mailer. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0812986099.

- Mailer, Norman (1959). Advertisements for Myself. New York: Putnam. OCLC 771096402.

- — (2014). Sipiora, Phillip (ed.). Mind of an Outlaw. New York: Random House. OCLC 862097015.

- Malaquais, Jean (1959). "Reflections on Hip". In Mailer, Norman (ed.). Advertisements for Myself. pp. 359–62.

- Manso, Peter (2008). Mailer: His Life and Times. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 9781416562863. OCLC 209700769.

- McKinley, Maggie (2017). Understanding Norman Mailer. Understanding Contemporary American Literature. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1611178050.

- Menand, Louis (January 5, 2009). "It Took a Village". The New Yorker. Critic at Large. pp. 36–45. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- Millett, Kate (2016) [1970]. "Norman Mailer". Sexual Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 327. ISBN 9780231174251.

- O'Neil, Paul (November 30, 1959). "The Only Rebellion Around". Life Magazine. 47 (22): 115+.

- Podhoretz, Norman (Spring 1958). "The Know-Nothing Bohemians". Partisan Review. 25 (2): 305+.

- Poirier, Richard (1972). Norman Mailer. Modern Masters. New York: Viking Press. OCLC 473033417.

- Polsky, Ned (1959). "Reflections on Hip". In Mailer, Norman (ed.). Advertisements for Myself. pp. 365–69.

- Rollyson, Carl (1991). The Lives of Norman Mailer. New York: Paragon House. ISBN 978-1557781932.

- Sorin, Gerald (2005). Irving Howe: A Life of Passionate Dissent. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814740200.

- Stern, Richard G. (1958). "Hip, Hell, and the Navigator". In Mailer, Norman (ed.). Advertisements for Myself. pp. 376–86.

- Tanner, Tony (1974). "On the Parapet". In Adams, Laura (ed.). Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Stand Up?. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press. pp. 113–149. ISBN 978-0804690669.

- Trilling, Diana (1972). "The Radical Moralism of Norman Mailer". In Braudy, Leo (ed.). Norman Mailer: A Collection of Critical Essays. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0135455333.

- Wenke, Joe (2013). Mailer's America. Stamford, CT: Trans Uber LLC. ISBN 978-0985900274.

External links

- Mailer, Norman (Fall 1957). "The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster". Dissent. 4: 276–93. Retrieved 2012-11-26. This online version is replete with errors, but is linked here because it remains perhaps the only free version available on the web.

- The White Negro on Project Mailer.