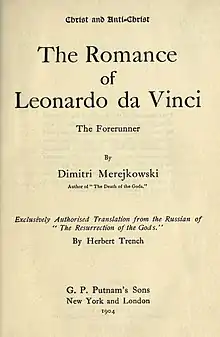

Title page of the 1904 authorized English translation | |

| Author | Dmitry Merezhkovsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Воскресшие боги. Леонардо да Винчи |

| Translator | Herbert Trench |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

Publication date | 1900 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback & Hardback) |

| Preceded by | The Death of the Gods |

The Romance of Leonardo da Vinci (Russian: Воскресшие боги. Леонардо да Винчи, Resurrected Gods. Leonardo da Vinci, in literal translation) is the second novel by Dmitry Merezhkovsky, first published in 1900 by Mir Bozhy magazine, then released as a separate edition 1901. The novel constitutes the second part of the Christ and Antichrist trilogy (1895-1907), started by the writer's debut novel The Death of the Gods.[1]

Background

.jpg.webp)

Merezhkovsky started working upon the second novel right after the first one, The Death of Gods, was finished, submerging himself in studying the history of Renaissance. By this time he had the vision of the trilogy as a whole. In 1896 with Zinaida Gippius (and accompanied by Severny Vestnik editor Akim Volynsky) he made a journey to Europe visiting places where Leonardo da Vinci had stayed while accompanying Francis I of France.

The plans of publishing the novel in Severny Vestnik had to be discarded after Volynsky whose advances had been rejected by Gippius, started to take revenge upon her husband, expelling him from Severny Vestnik and making sure all the major literary journals would shut the door on him.

Volynsky went so far as to publish under his own name some papers on Leonardo, written and compiled by his adversary, who then accused him of theft and plagiarism. For three years the second novel remained unpublished. It finally appeared in Autumn 1900 under the title "Renaissance", in Mir Bozhy (God's World), the editor of which, Anna Davydova, Merezhkovsky was on friendly terms with.[2]

Summary

The novel starts with the merchant Buonarcozzi digging out the statue of Venus, with Leonardo invited as an expert. This echoes the final scene of The Death of the Gods with Arsinoya's prophecy about "future brothers" who will dig out the precious bones of Hellas, and start worshipping them again. The adventures of the great artist and thinker of the Renaissance are set against the background of conflicts and tragedies, all going to show the new epoch's re-emerging humanism, harking back to the spirit of Antiquity and contrasting the monastic horrors of the Middle Ages.[2] The main character is a young man, Giovanni Beltraffio, who comes to study with Leonardo, and spends most of the novel wondering why he cannot paint as well as the master.

Reception

As its predecessor, the novel received mixed reviews, praised unreservedly only by the early 20th century Russian Modernist community. Other critics, acknowledging the author's skillfulness, found moral fault with his worldview. According to Alexander Men, Merezhkovsky demonstrated certain narrow-mindedness, "making Savonarola looking like a madman" and "portraying Leonardo according to abstract schemes obviously derived from Nietzsche."[3]

Other detractors have spotted Nietzchean influences, particularly in that the author "valued will power higher than morality" and saw Arts as being beyond the good and the evil. Modern critic Oleg Mikhaylov saw the novel as marked by tendentiousness, being driven by one motif, that of inevitable resurrection of Antiquity's gods and values.[4]

References

- ↑ D.O.Tchurakov. "Russian Decadent movement's esthetic, in the late XIX - early XX century. The Early Merezhkovsky and others. P.2". www.portal-slovo.ru. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- 1 2 Zobnin, Yuri. The Life and Deeds of Dmitry Merezhkovsky. Moscow. — Molodaya Gvardiya. 2008. Lives of Distinguished People series, issue 1091. ISBN 978-5-235-03072-5 pp. 400-404

- ↑ Menh, Alexander. "Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Zinaida Gippius (Lecture)". www.svetlana-and.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ↑ Mikhaylov, Oleg. The Works of D.S.Merezhkovsky in Four Volumes. The Prisoner of Culture (Foreword). — Pravda, 1990

External links

- Resurrected Gods. Leonardo da Vinci. The original Russian text.