| The Possession of Joel Delaney | |

|---|---|

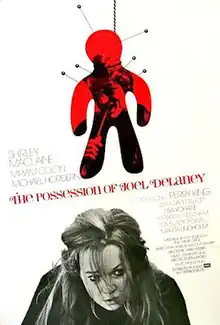

Original theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Waris Hussein |

| Screenplay by | Grimes Grice Matt Robinson |

| Based on | The Possession of Joel Delaney by Ramona Stewart |

| Produced by | Martin Poll |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Arthur J. Ornitz |

| Edited by | John Victor Smith |

| Music by | Joe Raposo |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (United States) Scotia-Barber (United Kingdom) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $1.5 million[2] |

The Possession of Joel Delaney is a 1972 horror film directed by Waris Hussein and starring Shirley MacLaine and Perry King. It is based on the 1970 novel of the same title by Ramona Stewart. The plot follows a wealthy New York City divorcee whose brother becomes possessed by a deceased serial killer who committed a series of gruesome murders in Spanish Harlem.

Originally developed by producer Martin Poll and his production company, Haworth Productions, Poll abandoned the project shortly after filming began, due to creative differences with actress Shirley MacLaine. Following Poll's departure, British producer Lew Grade of ITC Entertainment overtook the project. Principal photography took place in New York City and London during the winter of 1971, on a budget of $1.5 million.

The Possession of Joel Delaney was released theatrically in the United States by Paramount Pictures in May 1972, and subsequently entered competition at the 22nd Berlin International Film Festival. It received a theatrical release in the United Kingdom shortly after, in August 1972. The film received mixed reviews from critics, though its theme of possession subsequently resulted in parallels being drawn by critics to The Exorcist, released a year later.[3]

In the intervening years, the film has been the subject of film criticism surrounding its themes of social inequality, as well as familial relationships and incest.

Plot

Norah Benson is an upperclass Manhattan divorcee living with her two children, Carrie and Peter. Her ex-husband, Ted, an esteemed physician, has recently remarried. One night, Norah, accompanied by her younger brother, Joel Delaney, attends a party held by her psychologist friend, Erika Lorenz. In contrast to Norah's elitism, Joel has a more bohemian view of the world, and has recently returned to New York after an extended visit to Tangier. Despite their differences, the siblings remain close, bonded by the suicide of their socialite mother that occurred when Joel was still a child; Norah, a young adult at the time, became Joel's guardian.

Two days after Erika's party, Joel fails to arrive at a dinner Norah has planned at her house. When she phones him, she hears a series of disturbing noises and heavy breathing. Concerned, Norah rushes to Joel's apartment building in the East Village. Outside, she witnesses Joel in a rage, being apprehended by police and escorted to the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital. Norah is disturbed to find that Joel violently attacked the building's superintendent. In Joel's apartment, Norah finds a large switchblade knife, and notices an esoteric hand symbol painted on the wall. Norah is met by Joel's former girlfriend, Sherry, who comments on Joel's "dark side." Norah learns that the apartment previously belonged to a man named Tonio Pérez, the superintendent's son.

Unable to recall the events that landed him in the hospital, Joel is convinced by Norah to lie to the doctors and claim he was under the influence of hallucinogens. After following Norah's instruction, Joel is discharged on the provision that he meet with a psychiatrist; Norah arranges for him to see Erika, who has known Joel most of his life. During their sessions, Joel informs Erika that he formed a strong friendship with his neighbor, Tonio. Meanwhile, Norah, having welcomed Joel to stay with her while recovering, observes increasingly odd behavior: He first asks Norah inappropriate questions about her sex life, and later, at his birthday celebration (attended by Norah, her children, and Sherry), exhibits manic behavior, culminating in a series of crude insults to Norah's Puerto Rican maid, Veronica, which he relays in Spanish.

The following day, Norah visits Sherry's apartment to return an earring she left behind. Upon entering, Norah finds Sherry's decapitated corpse lying in her bed, and her severed head hanging from a houseplant. Police interview Norah, and remark that Sherry's murder resembles serial killings that occurred the summer before in Spanish Harlem, which received little publicity because the victims were all Hispanic females. Detectives presume the perpetrator to be Tonio Peréz, who has been missing for several months, but his family and friends refuse to cooperate with authorities.

With Veronica's help, Norah meets Don Pedro, a Santería practitioner in Harlem who agrees to help her. He arranges a ceremony to banish Tonio's spirit, which he believes has possessed Joel's body. In attendance is Tonio's grief-stricken mother, who admits to Norah that Tonio was in fact a murderer, and that when his father discovered Tonio's crimes, he murdered Tonio himself and disposed of his remains. Norah bears witness to the ceremony, but Don concludes it to be unsuccessful because Norah is not a believer; he insists she return with Joel.

Norah returns home to find Joel screaming hysterically in Spanish. Frightened for the children's safety, Norah brings them to the family's beachfront vacation home in Long Island, while Erika promises to help Joel. The next morning, after returning from a walk on the beach, Norah finds Erika's severed head in the kitchen, and Joel standing nearby with his switchblade. Now uniformly possessed by Tonio, Joel torments and taunts Norah and the children. He orders Peter to strip naked, and forces Carrie to eat dog food before superficially cutting her on her neck. Ted, along with police, arrive outside the home in the midst of this. Norah observes them and attempts to stop Joel, who responds by giving her a passionate kiss. The children flee outside. Joel pursues them, only to be shot in the chest by one of the officers. Norah rushes to her brother, who dies in her arms. After a pause, Norah picks up Joel's switchblade, and menacingly holds it up toward the policeman, indicating the spirit of Tonio has now resided within her.

Cast

- Shirley MacLaine as Norah Benson

- Perry King as Joel Delaney

- Michael Hordern as Justin

- Barbara Trentham as Sherry

- Míriam Colón as Veronica

- Earl Hyman as Charles

- David Elliott as Peter Benson

- Lisa Kohane as Carrie Benson

- Lovelady Powell as Erika

- Edmundo Rivera Álvarez as Don Pedro

- Teodorina Bello as Mrs. Pererz

- Robert Burr as Ted Benson

- Ernesto Gonzalez as Young Man at Seance

- Aukie Herger as Mr. Perez

- Marita Lindholm as Marta Benson

Themes

Social class

In his book Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film (2014), film scholar Tony Williams writes that The Possession of Joel Delaney is thematically preoccupied with the same "racial, economic, and class characteristics of I Walked With a Zombie (1943)," despite its depiction Puerto Rican Americans as "superstitious voodoo devotees."[4] Williams notes that the film's opening sequence at an upperclass party affirms this thematic exploration, observing that "intercut shots juxtapose affluent white guests with primitive voodoo masks placed in the demeaning position of trendy artifacts. A black man [in the scene] stands alone. His face exhibits ethnic alienation."[4]

Williams notes a similar social-racial suggestiveness through the film's cinematography, particularly "subtle, non-rhetorical camera movements" that occur during sequences between Norah and her maid, Veronica, which reveal the "oppressive nature of white power."[4]

Familial relationships

Familial trauma and incestual desire have been a points of discussion regarding the film, particularly between the lead characters of Norah and her brother, Joel.[5] Throughout the film, several peripheral characters observe that Norah and Joel have an unusual brother-sister relationship, with some commenting that the two appear to be a couple.[6] Williams attests that Norah's sexual desire for Joel is represented in the film's opening sequence, in which she appears visibly jealous when she witnesses Joel speaking with his ex-girlfriend.[6] According to Williams, Norah, who partly raised Joel, has an agenda to keep him in a "state of childish dependence," and suggests that the film's title has a double meaning, alluding to both the supernatural spirit possession of Joel, as well as the emotional possession of him by Norah.[7]

Williams believes that the film "handles family motifs far more successfully than the more publicized film from the following year, The Exorcist... it achieves an effective balance between supernatural motifs and material causes by never allowing the former to overwhelm the latter."[4]

Production

Development

Initially, producer Martin Poll and his studio, Haworth Productions, arranged to produce a film version of The Possession of Joel Delaney, based on Ramona Stewart's 1970 novel of the same name.[1] However, shortly after filming began, Poll left the project due to creative disputes with actress Shirley MacLaine.[1] Following Poll's exit, British media proprietor Lew Grade and his company, ITC Entertainment, took over the production; MacLaine had recently made the short-lived series Shirley's World under Grade's supervision.[2]

Filming

Filming of The Possession of Joel Delaney began on January 2, 1971 in New York City.[1] While exteriors were shot in New York, the bulk of the interior sequences were filmed in London.[1] Principal photography was completed in March 1971.[1]

Release

The film opened theatrically in the United States on May 24, 1972 in New York City and Los Angeles.[1] In addition to its standard cut, which consists primarily of spoken English with some Spanish, an exclusively Spanish-language version of the film was released concurrently in New York.[1] It was subsequently screened at the Berlin International Film Festival the week of June 23, 1972.[1] It was released in the United Kingdom approximately two months later, opening in London on August 18, 1972.[8]

Critical response

Candice Russell of the Miami Herald felt the screenplay was underdeveloped, despite the film's "keen performances, Hussein's crisp direction, and clean, often-eerie photography. The fault here lies with the screenplay, and not with its execution."[9]

Wanda Hale of The New York Daily News praised the acting in the film, noting that MacLaine's role "tests [her] dramatic ability, and she gives a remarkably fine performance," and also commented favorably on the film's depiction of class disparity among New York residents.[10]

A review published by the Time Out Film Guide was critical of the film, noting: "There is some slick racial moralising (rich white New Yorkers shouldn't be beastly to their less privileged neighbours). But stir in some mumbo-jumbo in which shrieking Puerto Ricans try to exorcise the devil, and a climax in which MacLaine and her children are tortured at knife-point by the spirit of racial vengeance, and what you come away with is an alarmist message saying 'Keep New York White'."[11] TV Guide also gave the film an unfavorable review, deeming it "bad taste, overwrought, and claptrap."[12]

Controversy

One of the more controversial elements of the film is its ending. Thirteen-year-old actor David Elliott is shown fully naked during a sequence in which his character is humiliated by the possessed Joel Delaney. Noted film critic Roger Ebert wrote:

[The] final scenes in the beach house are in nauseatingly bad taste. Filmmakers should have enough imagination and enterprise to scare us without resulting to cheap tricks. Hitchcock can, and does. But Warris Hussein, who directed this film, is so bankrupt of imagination that he actually descends to a scene where the little boy is forced to disrobe and eat dog food. This is all because of the evil spirit in Joel's body, of course, but I don't care. Scenes of this nature are rotten and bankrupt, and you feel unclean just watching them.[13]

In the March 5, 2004 issue of Entertainment Weekly, Stephen King wrote about the film and that particular scene, claiming that today it would earn the film an NC-17 rating. It was claimed that the VHS had the scene uncut, while the DVD was altered. In reality, the VHS transfer is "open matte," revealing top and bottom picture information usually cropped in theatrical showings; in this case, it made the scenes with the boy more revealing. In contrast, the DVD is matted widescreen, reflecting the theatrical intent of being more restrained about the boy's nudity.

Home media

Paramount Home Entertainment released The Possession of Joel Delaney on VHS in 1991.[14] The film remained unreleased in other formats until June 2008, when Paramount issued it for the first time on DVD in conjunction with Legend Films.[15] In August 2021, the Australian company Via Vision Entertainment announced they would be releasing the film for the first time on Blu-ray through their Imprint films series on November 24, 2021.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "The Possession of Joel Delaney". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- 1 2 Grade 1992, p. 221.

- ↑ Makowsky, Jennifer (November 1, 2011). "Before There Was 'The Exorcist', There Was 'The Possession of Joel Delaney'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Williams 2014, p. 161.

- ↑ Williams 2014, pp. 161–162.

- 1 2 Williams 2014, p. 162.

- ↑ Williams 2014, pp. 161–163.

- ↑ "London Theatres". The Guardian. August 18, 1972. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Russell, Candice (May 30, 1972). "'Joel Delaney' Short on Chills". Miami Herald. p. 44 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Hale, Wanda (May 25, 1972). "'Possession' Tale of Sorcery, Horror". New York Daily News. p. 112 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Possession of Joel Delaney". Time Out. Archived from the original on December 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Review: The Possession of Joel Delaney". TV Guide. Archived from the original on August 31, 2021.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (June 13, 1972). "The Possession of Joel Delaney". Chicago Sun-Times – via RogerEbert.com.

- ↑ The Possession of Joel Delaney (VHS). Paramount Home Entertainment. 1991 [1972]. 8111.

- ↑ Dahlke, Kurt (June 24, 2008). "Possession of Joel Delaney, The". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017.

- ↑ "The Possession of Joel Delaney (1972)". Via Vision. Archived from the original on August 31, 2021.

Sources

- Grade, Lew (1992). Still Dancing: My Story. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-002-17780-1.

- Williams, Tony (2014). Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film (Updated ed.). University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62846-107-7. OCLC 903533974.