Zodiac Killer | |

|---|---|

Composite sketch made in 1969 based on eyewitness accounts of the Presidio Heights murder | |

| Criminal status | Unidentified |

| Motive | Uncertain |

| Wanted since | 1968 |

| Details | |

| Victims | 5 confirmed dead, 2 injured, possibly 20–28 total dead (claimed to have killed 37) |

Span of crimes | 1968 – 1969 (confirmed)[n 1] |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California, possibly also Nevada |

| Location(s) | San Francisco Bay Area Napa Valley |

Date apprehended | Unapprehended |

The Zodiac Killer[n 2] is the pseudonym of an unidentified serial killer[1] who operated in Northern California in the late 1960s.[n 1] The case has been described as the most famous unsolved murder case in American history[2] and has become both a fixture of popular culture and a focus for efforts by amateur detectives.

The Zodiac murdered five known victims in the San Francisco Bay Area between December 1968 and October 1969, operating in rural, urban and suburban settings. He targeted young couples and a lone male cab driver. His known attacks took place in Benicia, Vallejo, unincorporated Napa County, and the city of San Francisco proper. Two of his wounded victims survived. The Zodiac also claimed to have murdered thirty-seven victims. He has been linked to several other cold cases, some in Southern California or outside the state.

The Zodiac coined his name in a series of taunting messages that he mailed to regional newspapers, in which he threatened killing sprees and bombings if they were not printed. Some of the letters included cryptograms, or ciphers, in which the killer claimed that he was collecting his victims as slaves for the afterlife. Of the four ciphers he produced, two remain unsolved, and one was cracked only in 2020. While many theories regarding the identity of the killer have been suggested, the only suspect authorities ever publicly named was Arthur Leigh Allen,[3] a former elementary school teacher and convicted sex offender who died in 1992.

Although the Zodiac ceased written communications around 1974, the unusual nature of the case led to international interest that has been sustained over half a century since.[4] The San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) marked the case "inactive" in April 2004, but re-opened it at some point prior to March 2007.[5][6] The case also remains open in the city of Vallejo, as well as in Napa and Solano counties.[7] The California Department of Justice has maintained an open case file on the Zodiac murders since 1969.[8]

Murders and correspondence

Confirmed murders

Although the Zodiac Killer claimed in messages to newspapers to have committed thirty-seven murders, investigators agree on seven confirmed assault victims, five of whom died and two survived. They are:

- David Arthur Faraday (17) and Betty Lou Jensen (16) were shot and killed on December 20, 1968, on Lake Herman Road, within the city limits of Benicia, California.

- Michael Renault Mageau (19) and Darlene Elizabeth Ferrin (22) were shot on July 4, 1969, in the parking lot of Blue Rock Springs Park in Vallejo, California. Mageau survived the attack; Ferrin was pronounced dead on arrival at Kaiser Foundation Hospital.

- Bryan Calvin Hartnell (20) and Cecelia Ann Shepard (22) were stabbed on September 27, 1969, at Lake Berryessa in Napa County, California. Hartnell survived, but Shepard died as a result of her injuries a couple of days later on September 29.

- Paul Lee Stine (29) was shot and killed on October 11, 1969, in the Presidio Heights neighborhood of San Francisco.

Lake Herman Road murders

The first murders widely attributed to the Zodiac were the shootings of high school students Betty Lou Jensen and David Arthur Faraday on December 20, 1968. The double-murder occurred on Lake Herman Road, just inside the city limits of Benicia. The couple were on their first date and planned to attend a Christmas concert at Hogan High School, about three blocks from Jensen's home. They visited a friend before stopping at a local restaurant and driving out on Lake Herman Road, a popular area for young couples.

At about 10:15 p.m., Faraday parked his mother's Rambler in a gravel turnout, which was a well-known lovers' lane. Shortly after 11:00 p.m., their bodies were found by Stella Borges, who lived nearby. The Solano County Sheriff's Department investigated the crime but no leads developed.[9]

Using available forensic data, author Robert Graysmith later speculated that another car pulled into the turnout just prior to 11:00 p.m. and parked beside the couple. The killer may have exited the second car and walked toward the Rambler, possibly ordering the couple out of it. It appeared that Jensen had exited the car first, but when Faraday was halfway out, the killer shot him in the head. The killer then shot Jensen five times in the back as she fled; her body was found twenty-eight feet from the car. The killer immediately drove away from the scene.[10]

Blue Rock Springs murder

Just before midnight on July 4, 1969, Darlene Ferrin and Michael Mageau parked their car at the Blue Rock Springs Park in Vallejo, four miles (6.4 km) from the Lake Herman Road murder site. While the couple sat in Ferrin's car, a second car drove into the lot and parked alongside them, but almost immediately drove away. Returning about ten minutes later, the second car parked behind them. The driver of the second car exited and approached the passenger side door of Ferrin's car, carrying a flashlight and a 9mm Luger. The killer directed the flashlight into Mageau's and Ferrin's eyes before shooting at them, firing five times. Both victims were hit, and several bullets passed through Mageau and into Ferrin. The killer walked away from the car but returned and shot each victim twice more before driving off.[11]

On July 5, 1969, at 12:40 a.m., a man phoned the Vallejo Police Department to report and claim responsibility for the attack. The caller also took credit for the murders of Jensen and Faraday six and a half months earlier. Police traced the call to a phone booth at a gas station at Springs Road and Tuolumne, located about three-tenths of a mile (500 m) from Ferrin's home and a few blocks from Vallejo police headquarters.[12] Ferrin was pronounced dead at the hospital. Mageau survived the attack despite being shot in the face, neck and chest.[13] He described his attacker as a 26-to-30-year-old, 195-to-200-pound (88 to 91 kg) or possibly even more, 5-foot-8-inch (1.73 m) white male with short, light brown curly hair.

First letters from the Zodiac

"I like killing people because it is so much fun it is more fun than killing wild game in the forrest because man is the most dangeroue anamal of all to kill something gives me the most thrilling experence it is even better than getting your rocks off with a girl the best part of it is thae when I die I will be reborn in paradice and all the I have killed will become my slaves I will not give you my name because you will try to sloi down or atop my collectiog of slaves for my afterlife ebeorietemethhpiti"

—The solution to Zodiac's 408-symbol cipher, solved in August 1969, including faithful transliterations of spelling and grammar errors in the original. The meaning, if any, of the final eighteen letters has not been determined.[n 3][14]

On August 1, 1969, three letters purportedly prepared by the killer were received at the Vallejo Times Herald, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the San Francisco Examiner. The nearly identical letters, subsequently described by a psychiatrist to have been written by "someone you would expect to be brooding and isolated",[15] took credit for the shootings at Lake Herman Road and Blue Rock Springs. Each letter also included one-third of a 408-symbol cryptogram which the killer claimed contained his identity. The killer demanded they be printed on each paper's front page, or else he would "cruse [sic] around all weekend killing lone people in the night then move on to kill again, until I end up with a dozen people over the weekend."[16]

The Chronicle published its third of the cryptogram on page four of the next day's edition. An article printed alongside the code quoted Vallejo Police Chief Jack E. Stiltz as saying, "We're not satisfied that the letter was written by the murderer" and requested the writer send a second letter with more facts to prove his identity.[17] The threatened murders did not happen, and all three parts of the cryptogram were eventually published.

On August 7, the Examiner received a letter with the salutation, "Dear Editor This is the Zodiac speaking." This was the first time the killer had used this name for identification. The letter was a response to Stiltz's request for more details that would prove he had killed Faraday, Jensen and Ferrin. In it, the Zodiac included details about the murders that had not yet been released to the public. He also said that when the police cracked his code "they will have me".[18]

The following day, Donald and Bettye Harden of Salinas cracked the 408-symbol cryptogram. It contained a misspelled message in which the killer seemed to reference "The Most Dangerous Game", a 1924 short story by Richard Connell. The author also said that he was committing the killings in order to collect slaves for his afterlife.[n 4] No name appears in this decoded text. The killer said that he would not give away his identity because it would slow down or stop his slave collection.[14]

Lake Berryessa murder

On September 27, 1969, Pacific Union College students Bryan Hartnell and Cecelia Shepard were picnicking at Lake Berryessa on a small island connected by a sand spit to Twin Oak Ridge. A white male, about 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m) weighing more than 170 pounds (77 kg), approached the couple wearing a black executioner's-type hood with clip-on sunglasses over the eyeholes and a bib-like device on his chest that had a white three-by-three-inch (7.6 cm × 7.6 cm) cross-circle symbol on it. The hooded man approached with a gun, which Hartnell believed to be a .45, and claimed to be an escaped convict from a jail with a two-word name, in either Colorado or Montana (a police officer later inferred that the man had been referring to a jail in Deer Lodge, Montana), where he had killed a guard and subsequently stolen a car. He then said that he needed their car and money to travel to Mexico because the stolen vehicle was "too hot".[20]

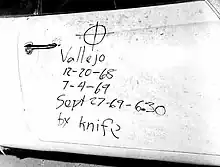

The killer had brought precut lengths of plastic clothesline and told Shepard to tie up Hartnell before the killer did the same with her. The killer checked, and tightened Hartnell's bonds after discovering that Shepard had bound them loosely. Hartnell initially believed this event to be a bizarre robbery, but the man drew a knife and stabbed them both repeatedly. Hartnell suffered six wounds and Shepard ten in the process.[21][22] The killer then hiked 500 yards (460 m) up to Knoxville Road, drew the cross-circle symbol on Hartnell's car door with a black felt-tip pen, and wrote beneath it:[23][24]

At 7:40 p.m., the killer called the Napa County Sheriff's Department from a pay telephone at a car wash in downtown Napa. The caller first stated to the operator that he wished to "report a murder – no, a double murder,"[25] before saying that he had committed the crime. KVON radio reporter Pat Stanley found the phone, still off the hook, a few minutes later. The phone was located a few blocks from the sheriff's office, and 27 miles (43 km) from the crime scene. Detectives lifted a still-wet palm print from the phone but were never able to match it to any suspect.[26]

After hearing the victims' screams for help, a man and his son fishing in a nearby cove discovered Hartnell and Shepard and got help by contacting park rangers. Napa County deputies Dave Collins and Ray Land were the first law enforcement officers to arrive at the crime scene.[27] Shepard was conscious when Collins arrived and provided him a detailed description of the attacker. She and Hartnell were taken to Queen of the Valley Hospital in Napa by ambulance. Shepard lapsed into a coma during transport, never regained consciousness, and died two days later. Hartnell survived to recount his tale to the press.[28][29] Napa County detective Ken Narlow, who was assigned to the case from the outset, worked on solving the crime until his retirement from the department in 1987.[30]

Presidio Heights murder

Two weeks later, on October 11, 1969, a white male passenger entered the taxi driven by Paul Stine at the intersection of Mason and Geary Streets (one block west from Union Square) in downtown San Francisco, requesting to be driven to Washington and Maple streets in Presidio Heights. For reasons unknown, Stine drove one block past Maple to Cherry Street. At approximately 9:55 p.m., the passenger shot Stine once in the head with a 9mm handgun, took his wallet and car keys, and tore away a section of his bloodstained shirt tail. Three teenagers across the street witnessed the incident and phoned the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) while the crime was in progress. They observed the killer wiping the cab down before walking away toward the Presidio, one block to the north.[31]

Two blocks from the crime scene, patrol officers Don Fouke and Eric Zelms, responding to the call, observed a white male walking along the sidewalk east on Jackson Street and stepping onto a stairway leading up to the front yard of one of the residential homes on the north side of the street; the encounter lasted only five to ten seconds.[32]

Fouke estimated the pedestrian to be 35 to 45 years old, 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) tall with a crew cut, similar to but slightly older and taller than the description provided by the teenaged witnesses. The teenagers described the suspect to be 25 to 30 years old with a crew cut, standing approximately 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) to 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) tall. However, the police radio dispatcher had alerted officers to look out for a black suspect, so Fouke and Zelms drove past the perpetrator without stopping; the mixup in descriptions remains unexplained. A search ensued, but no suspects were found. This was the last officially confirmed murder by the Zodiac Killer.

The Stine murder was initially believed to be a routine robbery that had escalated into homicidal violence. However, on October 13, the Chronicle received a new letter from the Zodiac that claimed credit for the killing and contained a torn section of Stine's bloody shirt as proof.[33] The letter also included a threat about killing schoolchildren on a school bus. To do this, Zodiac wrote, "just shoot out the front tire & then pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out".

The teenaged witnesses worked with a police artist to prepare a composite sketch of Stine's killer; a few days later, this police artist returned, working with the witnesses to prepare a second composite sketch. SFPD detectives Bill Armstrong and Dave Toschi were assigned to the case.[n 5] The SFPD investigated an estimated 2,500 suspects over a period of years.[35]

1969 mailings

"I hope you are having lots of fan in trying to catch me that wasnt me on the tv show which bringo up a point about me I am not afraid of the gas chamber becaase it will send me to paradlce all the sooher because e now have enough slaves to worv for me where every one else has nothing when they reach paradice so they are afraid of death I am not afraid because i vnow that my new life is life will be an easy one in paradice death"

—The solution to Zodiac's 340-symbol cipher, solved in December 2020, including faithful transliterations of spelling and grammar errors in the original.[n 6][2][36]

At 2:00 a.m. on October 22, 1969,[37] someone claiming to be the Zodiac called the Oakland Police Department (OPD), demanding that one of two prominent lawyers, F. Lee Bailey or Melvin Belli, appear that morning on A.M. San Francisco, a talk show on KGO-TV hosted by Jim Dunbar. Bailey was not available, but Belli agreed to appear. Dunbar appealed to the viewers to keep the lines open. Someone claiming to be the Zodiac called several times, and Belli asked the caller for a less ominous name and the caller picked "Sam". The caller said he would not reveal his true identity as he was afraid of being sent to the gas chamber (then California's capital punishment method). Belli arranged a rendezvous to meet the caller outside a shop on Mission Street in Daly City, but no one arrived. The call was later traced back to a mental patient named Eric Weill, who investigators concluded was not the Zodiac.[38]

On November 8, the Zodiac mailed a card with another cryptogram consisting of 340 characters.[39] This cipher, dubbed "Z-340", remained unsolved for over fifty-one years. On December 5, 2020, it was deciphered by an international team of private citizens, including American software engineer David Oranchak, Australian mathematician Sam Blake and Belgian programmer Jarl Van Eycke. In the decrypted message, the Zodiac denied being the "Sam" who spoke on A.M. San Francisco, explaining that he was not afraid of the gas chamber "because it will send me to paradice [sic] all the sooner".[2] The team submitted their findings to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which verified the discovery.[2] The FBI stated that the decoded message gave no further clues to the identity of Zodiac.[40][41]

On November 9, the Zodiac mailed a seven-page letter stating that two policemen stopped and actually spoke with him three minutes after he had shot Stine. Excerpts from the letter were published in the Chronicle on November 12, including the Zodiac's claim;[42][43] that same day, Fouke wrote a memo explaining what had happened on the night of Stine's murder. On December 20, exactly one year after the first two murders, the Zodiac mailed a letter to Belli that included another swatch of Stine's shirt; the Zodiac said that he wanted Belli to help him.[44]

Suspected victims

There is no consensus on the number of victims that the Zodiac had or the length of his criminal spree. In the 1986 non-fiction book Zodiac, author Graysmith published a list attributing forty-nine victims to the Zodiac.[45] This list included some crimes which have since either been solved or whose links to the Zodiac have been disproven by investigators. Various other authors speculated at the time of the killings that several other high-profile murders and attacks may have been the work of the Zodiac, but none have been confirmed:

- Local historian Kristi Hawthorne suggests that the Zodiac may have murdered 29-year-old cab driver Raymond Davis in Oceanside, California, on April 10, 1962. The day before the murder, an individual believed to be the culprit had phoned the Oceanside police and told them, "I am going to pull something here in Oceanside and you'll never be able to figure it out." A few days later, the police received another call from someone who is presumed to be the same individual in which he told police details of the murder and said he would kill a bus driver next. Following Hawthorne's research, Oceanside police announced that they were looking into possible connections between the Davis murder and the Zodiac.[46][47][48][49]

- Bill Baker of the Santa Barbara County Sheriff's Department has postulated that the 1963 murders of a young couple in his jurisdiction might have been the work of the Zodiac.[50] On June 4, 1963, 18-year-old Robert George Domingos and his fiancée, 17-year-old Linda Faye Edwards, were shot dead on a beach near Lompoc, having skipped school that day for Senior Ditch Day. Police believed that the assailant attempted to bind the victims, but when they freed themselves and attempted to flee, the killer shot them repeatedly in the back and chest with a .22 caliber weapon. The killer then placed their bodies in a small shack and then tried, unsuccessfully, to burn the structure to the ground.[51]

- On February 5, 1964, Johnny Ray Swindle and Joyce Ann Swindle (both aged 19), a newlywed couple from Alabama, were gunned down while walking along Ocean Beach in San Diego while on their honeymoon. Their killer, who was on a nearby cliff with a .22 caliber rifle, shot them from a distance. Johnny remained alive for hours, despite bullet wounds to his back, left thigh, left ear, and temple. Joyce died almost instantly after she was shot in the back, left arm and head. The suspect took Johnny's wallet when he succumbed to his wounds and left the crime scene. Police speculated that the two were victims of a "thrill killer" and Rita, Johnny's sister, has theorized that the murders might have been the work of the Zodiac.[52]

- On June 8, 1967, Enedine Molina Martinez, aged 35, and Fermin Rodriguez, aged 36, were attacked and murdered on Vallecitos Road in Alameda County while relaxing in their vehicle. A stranger approached the couple and told them to get out of the car. Rodriguez was shot dead as he exited the car and the killer abducted Martinez. The killer then stopped by the entrance of Sunol Regional Wilderness, where Martinez was killed trying to escape. Shortly afterward, a nearby resident called the Santa Rita police substation to report two gunshots, resulting in the discovery of the bodies. Rape and robbery were ruled out as motives. The murders occurred close to Pleasanton, where the Zodiac mailed a letter to the Los Angeles Times in March 1971.[53]

- On February 21, 1970, 24-year-old Vietnam War veteran John Franklin Hood and his fiancée, 20-year-old Sandra Garcia, visited East Beach in Santa Barbara. The couple were discovered the following day lying face down on their blanket. Hood suffered eleven knife wounds, the majority inflicted to his face and back, while Garcia received the brunt of the vicious attack, leaving her almost unrecognisable. The bone-handled 4" fish knife used in their murder was retrieved from beneath the blanket, partially buried in the sand. There appeared to be no sexual interference and robbery was ruled out. The double-murder bore many similarities to the previous murders of Domingos and Edwards, thirty miles west of the attack and seven years earlier, as well as the Lake Berryessa attack on Hartnell and Shepard.[54]

- On June 19, 1970, 25-year-old police sergeant Richard Phillip “Rich” Radetich was gunned down by three shots from a .38 caliber revolver through the driver side window of his squad car, while in the process of serving a parking ticket on the 600 block of Waller Street in the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco. Police investigated a possible link to the Zodiac, who alluded to the crime in taunting notes to authorities; however, no direct evidence has ever been established between Radetich's death and the Zodiac.[55]

Cheri Jo Bates

On October 30, 1966, Cheri Jo Bates, an 18-year-old student at Riverside City College (RCC), spent the evening at the campus library annex until it closed at 9:00 p.m. Neighbors reported hearing a scream around 10:30 p.m. Bates was found dead the next morning, a short distance from the library, between two abandoned houses slated to be demolished for campus renovations. She had been brutally beaten and stabbed to death. The wires in her Volkswagen's distributor cap had been pulled out. A man's Timex watch with a torn wristband was found nearby.[56] The watch had stopped at 12:24,[57] but police believe that the attack had occurred much earlier.[56]

One month later, on November 29, nearly identical typewritten letters were mailed to the Riverside police and the Riverside Press-Enterprise, titled "The Confession". The author claimed responsibility for the Bates murder, providing details of the crime that were not released to the public. The author warned that Bates "is not the first and she will not be the last".[58] In December 1966, a poem was discovered carved into the bottom side of a desktop in the RCC library. Titled "Sick of living/unwilling to die", the poem's language and handwriting resembled that of the Zodiac's letters. It was signed with what were assumed to be the initials rh. During the 1970 investigation, Sherwood Morrill, California's top "questioned documents" examiner, expressed his opinion that the poem was written by the Zodiac.[59]

On April 30, 1967, exactly six months after the Bates murder, her father, the Press-Enterprise, and the Riverside police all received nearly identical letters. In handwritten scrawl, the Press-Enterprise and police copies read, "Bates had to die there will be more" with a small scribble at the bottom that resembled the letter Z. Bates' father's copy read, "She had to die there will be more," this time without the Z signature.[60] In August 2021, the Riverside Police Department's cold case unit announced that the author of the handwritten letters anonymously contacted investigators in 2016 and was identified via DNA analysis in 2020. He admitted the correspondence was a distasteful hoax and apologized, explaining that he had been a troubled teenager and wrote the letters as a means of seeking attention. Investigators confirmed that the author was not the Zodiac.[61]

On March 13, 1971, five months after Avery's article linking the Zodiac to the Bates murder, the Zodiac mailed a letter to the Los Angeles Times. In the letter, he credited the police, instead of Avery, for discovering his "Riverside activity, but they are only finding the easy ones, there are a hell of a lot more down there".[62] The connection between Bates and the Zodiac remains uncertain. Avery and the Riverside police maintain that the Bates homicide was not committed by the Zodiac but did concede that some of the Bates letters may have been his work to claim credit falsely.[63]

Kathleen Johns

On the night of March 22, 1970, Kathleen Johns was driving from San Bernardino to Petaluma to visit her mother. Johns was seven months pregnant and was accompanied by her ten-month-old daughter.[64] While she was heading west on Highway 132 near Modesto, a car behind her began honking its horn and flashing its headlights. Johns pulled off the road and stopped. The man in the car parked behind her, approached her car, stated that he observed that her right rear wheel was wobbling, and offered to tighten the lug nuts. After finishing his work, the man drove off; yet, when Johns pulled forward to re-enter the highway, the wheel almost immediately came off the car. The man returned, offering to drive her to the nearest gas station for help. Johns and her daughter climbed into his car.[65]

During the ride, the car passed several service stations, but the man did not stop. For about ninety minutes, he drove back and forth around the back roads near Tracy. When Johns asked why he was not stopping, he would change the subject. When the driver finally stopped at an intersection, Johns jumped out with her daughter and hid in a field. The driver searched for her using a flashlight, telling her that he would not hurt her, before eventually giving up and driving off. Johns hitched a ride to the police station in Patterson.[66]

When Johns gave her statement to the sergeant on duty, she noticed the composite sketch from the Stine killing and recognized the man who had abducted her and her child.[67] Fearing that he might return to kill them all, the sergeant had Johns wait in the dark at a nearby restaurant. When Johns' car was found, it had been gutted and torched.[67]

Most accounts say that the man threatened to kill Johns and her daughter while driving them around,[68] but at least one police report disputes that.[66] Johns' account to Avery of the Chronicle indicates that her abductor left his car and searched for her in the dark with a flashlight;[69] however, in one report she made to the police, she stated that he did not leave the vehicle.[66]

Donna Lass

On March 22, 1971, a postcard to the Chronicle, addressed to "Paul Averly" [sic] and believed to be from the Zodiac, appeared to claim responsibility for the disappearance of Donna Lass.[70] Made from a collage of advertisements and magazine lettering, it featured a scene from an advertisement for Forest Pines condominiums and the text "Sierra Club", "Sought Victim 12",[71] "peek through the pines", "pass Lake Tahoe areas", and "around in the snow". The Zodiac's crossed-circle symbol was in both the place of the usual return address and the lower-right section of the front face of the postcard.[72]

Lass was working as a registered nurse at the first aid station at the Sahara Tahoe hotel and casino. She worked until about 2:00 a.m. on September 6, 1970,[72] treating her last patient at 1:40 a.m. and her last logbook entry was timed at 1:50 a.m. Later that same day, both Lass' employer and her landlord received phone calls from an unknown male falsely claiming that Lass had left town because of a family emergency.[73] Lass did not have a family emergency at the time. Lass was never found and the caller has never been identified. Her car was found parked near her apartment in Stateline, Nevada, but nobody saw her leave the casino. All of her personal belongings were left behind at her home, except her purse and the clothes she was wearing the night she vanished.

On December 27, 1974, a Christmas card was mailed to Mary Pilker, Lass' sister, portraying trees covered in snow. Once opened it revealed a message that was part of the card itself – "Holiday Greetings and Best Wishes for a Happy New Year", followed by the handwriting "Best Wishes, St. Donna & Guardian of the Pines". The envelope was addressed to "Mrs. Mary Pilker, 1609 South Grange, Sioux Falls, South Dakota." It was postmarked 940, either from San Mateo or Santa Clara County.

In 1986, the Placer County Sheriff's Office located a human skull in the vicinity of California State Route 20 and Interstate 80. In 2023, DNA profiling identified the skull as Lass's. Police said no other evidence was found with the skull, and did not indicate how Lass died or whether homicide was suspected.[74] No evidence has been uncovered to definitively connect the Lass disappearance with the Zodiac.

Potentially related serial murders

Astrological murders

The "Astrological Murders" were allegedly committed by a suspected serial killer who was also active in the same state and around the same time as the Zodiac. Police in Northern California made a tentative connection between a single culprit and possibly at least a dozen unsolved homicides that occurred between the late 1960s and early 1970s.[75] All of the alleged victims were female and were allegedly killed in a variety of ways, including strangulation, drowning, throat-cutting, and bludgeoning, occasionally after being drugged. They were linked by the fact that they were dumped in ravines and killed in conjunction with astrological events, such as the winter solstice, equinox, and Friday the 13th.[76] The alleged victims are:

- Elaine Louise Davis, aged 17, who disappeared on December 1, 1969, from her home in Walnut Creek, California. On December 19, the body of a young woman – eventually identified as Davis after an exhumation in 2000 – was discovered floating off Light House Point near Santa Cruz.[77][78]

- Leona LaRell Roberts, aged 16, whose nude body was found ten days before the winter solstice on the beach at Bolinas Lagoon in Marin County, on December 28, 1969. She had been kidnapped from her boyfriend's home on December 10. Her death was treated as a homicide, although the official cause was listed as "exposure" by the medical examiner.[79][80]

- Cosette Ann Ellison, aged 15, whose nude body was found in a ravine seventeen days before the vernal equinox; the cause of her death was undetermined. She had been abducted on March 3, 1970, from her residence in Moraga, California, as she got off the school bus at 3:20 p.m.[81]

- Patricia Ann King, aged 20, was found strangled and discarded in a rural gully at Diablo Valley College. She was nude from the waist down but had not been raped.[82]

- Judith Ann Hakari, aged 23, was last seen leaving work at Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento at 11:30 p.m. on March 7, 1970,[83] thirteen days before the equinox; she was discovered, nude and bludgeoned, in an overgrown ravine off Ponderosa Way, near Weimar on April 26.[84]

- Marie Antoinette Anstey, aged 23, who was kidnapped in Vallejo after being stunned by a blow to the head, and then drowned; her body was recovered in rural Lake County on March 21, and an autopsy revealed traces of mescaline in her bloodstream.[85]

- During the equinox on March 20, 1970, 17-year-old Eva Lucienne Blau was found clubbed to death and dumped in a roadside gully near Santa Rosa; the medical examiner discovered drugs in her circulatory system. She was last seen on March 12, leaving Jack London Hall after telling friends that she was heading home.[86]

- Carol Beth Hilburn, aged 22, was found beaten to death in a ravine on November 13, 1970. She was last seen at Lloyd Hickey’s Forty Grand Club in Sacramento on November 14 at approximately 5:00 a.m.[87] Hilburn had been stripped of her clothing except for her underwear, which was found around her knees. She had been beaten about the face, and had a deep cut to her throat.

- Denise Kathleen Anderson, aged 22, who disappeared on April 13, 1971, having been last seen by one of her roommates at 5:30 a.m. at their residence in Sacramento. She has not been seen since.[88][89]

- Susan Marie Lynch, aged 22, was discovered murdered on July 31, 1971, having been buried alive near East Levee Road in Sacramento, one-half mile north of Del Paso Road and 0.6 miles southwest of the Hilburn dump site.[90]

- Linda Diane Ohlig, aged 19, was found in a ditch alongside a rural road beaten to death at Half Moon Bay on March 28, 1972, six days after the vernal equinox. Her skull had been smashed and it appeared that her attacker had tried to decapitate her.[91]

- Lynn Derrick, aged 24, was discovered in Noe Valley, San Francisco, on July 26, 1972, at 4:15 a.m. She had been strangled and a sock had been forced into her mouth, but no sexual molestation had taken place. Derrick had been abducted from her home approximately two hours earlier, at around 2:00 a.m., when a female neighbour reported hearing a disturbance, a dragging sound, and a car speeding away.[92]

Santa Rosa hitchhiker murders

The Zodiac was also suspected of being the perpetrator behind the so-called "Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders", in which at least seven female hitchhikers were all murdered in Sonoma County and Santa Rosa between 1972 and 1973.[93] The suspicion was based upon similarities between an unknown symbol on his January 29, 1974, "Exorcist letter" to the Chronicle, in which he claims thirty-seven victims,[94] and the Chinese characters on the missing soy barrel carried by victim Kim Allen,[95] as well as stating an intention to vary his modus operandi in an earlier letter to the Chronicle: "I shall no longer announce to anyone. when I comitt my murders, they shall look like routine robberies, killings of anger, + a few fake accidents, etc." (sic)[96] The ligature strangulation of some of these victims is in line with the Zodiac's October 1970 claim to kill by "Rope."

In addition, Zodiac suspect Arthur Leigh Allen was independently suspected of being the Santa Rosa killer.[97] He owned a mobile home in Santa Rosa at the time of the murders,[98] had been fired from his Valley Springs teaching position for suspected child molestation in 1968,[99] and was a full-time student at Sonoma State University.[100] Allen was arrested on September 27, 1974, by the Sonoma County Sheriff's Office[101] and charged with child molestation in an unrelated case involving a young boy.[102] He pleaded guilty on March 14, 1975, and was imprisoned at Atascadero State Hospital until late 1977.[103] Graysmith, in his book Zodiac Unmasked, claims that a Sonoma County sheriff revealed that chipmunk hairs were found on all of the Santa Rosa victims and that Allen had been collecting and studying the same species.[104][97][99]

Further Zodiac communications

Zodiac continued to communicate with authorities for the remainder of 1970 via letters and greeting cards to the press. In a letter postmarked April 20, 1970, he wrote, "My name is _____," followed by a 13-character cipher that has not been solved to this day.[105] The Zodiac went on to state that he was not responsible for the recent bombing of a police station in San Francisco (referring to the February 18, 1970, death of Sgt. Brian McDonnell two days after the bombing at Park Station in Golden Gate Park)[106] but added "there is more glory to killing a cop than a cid [sic] because a cop can shoot back." The letter included a diagram of a bomb the Zodiac claimed that he would use to blow up a school bus. At the bottom of the diagram, he wrote: "![]() = 10, SFPD = 0."[107]

= 10, SFPD = 0."[107]

On a greeting card to the Chronicle postmarked April 28, 1970, the Zodiac wrote, "I hope you enjoy yourselves when I have my BLAST," followed by the killer's cross-circle signature. On the back of the card, the Zodiac threatened to use the bus bomb soon unless the newspaper published the full details that he had written. He also wanted to start seeing people wearing "some nice Zodiac butons [sic]".[108]

In a letter postmarked June 26, 1970, the Zodiac stated that he was upset that he did not see people wearing Zodiac buttons, writing, "I shot a man sitting in a parked car with a .38."[109] The Zodiac was possibly referring to the murder of SFPD Sergeant Richard Radetich, who was killed one week earlier after being shot through the window of his squad car by an unidentified gunman during a routine traffic stop.[110] The SFPD denies that the Zodiac was involved in Radetich's death; the murder remains unsolved.[106]

Included with the Radetich letter was a Phillips 66 roadmap of the San Francisco Bay Area. On the image of Mount Diablo, the Zodiac had drawn a crossed circle similar to those from previous correspondence. At the top of the crossed circle, he placed a zero, a three, six, and a nine. The accompanying instructions stated that the zero was "to be set to Mag. N."[111] The letter also included a 32-letter cipher that the killer claimed would, in conjunction with the code, lead to the location of a bomb that he had buried and set to detonate in the fall. The cipher was never decoded, and the alleged bomb was never located. The killer signed the note with "![]() - 12, SFPD - 0".

- 12, SFPD - 0".

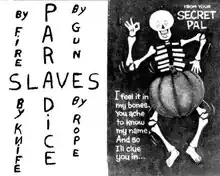

In a letter postmarked July 24, 1970, the Zodiac took credit for the Kathleen Johns abduction, four months after the incident.[112] In a July 26, 1970, letter, the Zodiac paraphrased a song from The Mikado, adding his own lyrics about making a "little list" of the ways in which he planned to torture his "slaves" in "paradice [sic]".[113] The letter was signed with a large, exaggerated crossed-circle symbol and a new score: "![]() = 13, SFPD = 0".[114] A final note at the bottom of the letter stated, "P.S. The Mt. Diablo code concerns Radians + # inches along the radians."[115] In 1981, a close examination of the radian hint by Zodiac researcher Gareth Penn led to the discovery that a radian angle, when placed over the map per Zodiac's instructions, pointed to the locations of two Zodiac attacks.[116]

= 13, SFPD = 0".[114] A final note at the bottom of the letter stated, "P.S. The Mt. Diablo code concerns Radians + # inches along the radians."[115] In 1981, a close examination of the radian hint by Zodiac researcher Gareth Penn led to the discovery that a radian angle, when placed over the map per Zodiac's instructions, pointed to the locations of two Zodiac attacks.[116]

On October 7, 1970, the Chronicle received a three-by-five inch card signed by the Zodiac with the ![]() symbol and a small cross reportedly drawn with blood. The card's message was formed by pasting words and letters from an edition of the Chronicle, and thirteen holes were punched across the card. Inspectors Armstrong and Toschi agreed that it was "highly probable" that the card had been sent by the Zodiac.[117]

symbol and a small cross reportedly drawn with blood. The card's message was formed by pasting words and letters from an edition of the Chronicle, and thirteen holes were punched across the card. Inspectors Armstrong and Toschi agreed that it was "highly probable" that the card had been sent by the Zodiac.[117]

Letter to Paul Avery

On October 27, 1970, Avery received a Halloween card signed with a letter Z and the Zodiac's crossed-circle symbol. Handwritten inside the card was the note, "Peek-a-boo, you are doomed." The threat was taken seriously and was the subject of a front-page story in the Chronicle.[118] Soon after receiving the letter, Avery received an anonymous letter alerting him to the similarities between the Zodiac's activities and the unsolved Bates murder in Riverside.[119] Avery reported his findings in the Chronicle on November 16, 1970.

Final Zodiac letter

After the Lake Tahoe card, the Zodiac remained silent for nearly three years. The Chronicle then received a letter from the Zodiac, postmarked January 29, 1974, praising the film The Exorcist (1973) as "the best saterical comidy [sic] that I have ever seen". The letter included a snippet of verse from The Mikado and an unusual symbol at the bottom that has remained unexplained by researchers. Zodiac concluded the letter with a new score, "Me = 37, SFPD = 0".[120]

Later letters of suspicious authorship

Of further communications sent by the public to members of the news media, some contained similar characteristics of previous Zodiac writings. The Chronicle received a letter postmarked February 14, 1974, informing the editor that the initials for the Symbionese Liberation Army, a radical group which had recently kidnapped heiress Patricia Hearst, spelled out an Old Norse word meaning "kill".[121] However, the handwriting was not authenticated as the Zodiac's.[122]

A letter to the Chronicle, postmarked May 8, 1974, featured a complaint that the movie Badlands (1973) was "murder-glorification" and asked the paper to cut its advertisements. Signed only "A citizen", the handwriting, tone, and surface irony were all similar to earlier Zodiac communications.[123] The Chronicle subsequently received an anonymous letter postmarked July 8, 1974, complaining of their publishing the writings of the antifeminist columnist Marco Spinelli. The letter was signed "the Red Phantom (red with rage)". The Zodiac's authorship of this letter is debated.[123]

One letter, dated April 24, 1978, was initially deemed authentic but was declared a hoax less than three months later by three experts. Dave Toschi, one of the SFPD homicide detectives who had worked the Zodiac case since the Stine murder, was thought to have forged the letter. Author Armistead Maupin believed the letter to be similar to "fan mail" that praised the work of Toschi in the investigation, which he received in 1976; he believed both letters were written by Toschi. While Toschi admitted to writing the fan mail, he denied forging the Zodiac letter and was eventually cleared of any charges. The authenticity of this letter remains unverified.

On March 3, 2007, an American Greetings Christmas card sent to the Chronicle, postmarked 1990 in Eureka, was re-discovered in the paper's photo files by editorial assistant Daniel King. This letter was handed over to the Vallejo police.[124] Inside the envelope, with the card, was a photocopy of two United States Post Office keys on a magnet keychain. The handwriting on the envelope resembles Zodiac's print but was declared inauthentic by forensic document examiner Lloyd Cunningham; however, not all Zodiac experts agree with Cunningham's analysis.[125] There is no return address on the envelope nor is his crossed-circle signature present. The card itself is unmarked.

21st-century developments

In April 2004, the SFPD marked the case "inactive", citing caseload pressure and resource demands, effectively closing the case.[126][127] However, they re-opened their case sometime before March 2007.[6][128] The case is open in Napa County[129] and in the city of Riverside.[130]

In May 2018, the Vallejo Police Department announced their intention to attempt to collect the Zodiac's DNA from the back of stamps he used during his correspondence. The analysis, by a private laboratory, was expected to check the DNA against GEDmatch.[131][132] It was hoped the Zodiac would be caught in a similar fashion to serial killer Joseph James DeAngelo. In May 2018, a Vallejo police detective said that results were expected in several weeks. As of October 2022, no results have been reported.[133][134][135]

Suspects

Arthur Leigh Allen

In his book Zodiac, author Graysmith advanced Arthur Leigh Allen, who died in 1992, as a potential suspect based on circumstantial evidence. Allen had been interviewed by police from the early days of the Zodiac investigations and was the subject of several search warrants over a twenty-year period. In 2007, Graysmith noted that several detectives described Allen as the most likely suspect.[136] In 2010, Dave Toschi stated that all the evidence against Allen ultimately "turned out to be negative".[137] Toschi's daughter said in 2018 that her father had always thought Allen had been the killer, but they did not have the evidence to prove it. Mark Ruffalo, who portrayed Toschi in the 2007 film adaptation of Graysmith's book, commented, "If you get into who these cops were, you realize how they have to take their hunches, their personal beliefs, out of it. Dave Toschi said to me, 'As soon as that guy walked in the door, I knew it was him.' He was sure he had him, but he never had a solid piece of evidence. So he had to keep investigating every other lead."[138]

On October 6, 1969, Allen was interviewed by Detective John Lynch of the Vallejo Police Department. Allen had been reported in the vicinity of the Lake Berryessa attack on September 27, 1969; he described himself scuba diving at Salt Point on the day of the attacks.[139] Allen again came to police attention in 1971 when his friend Donald Cheney reported to police in Manhattan Beach that Allen had spoken of his desire to kill people, used the name Zodiac, and secured a flashlight to a firearm for visibility at night. According to Cheney, this conversation occurred no later than January 1, 1969.[140]

Jack Mulanax of the Vallejo Police Department subsequently wrote that Allen had received a dishonorable discharge from the United States Navy in 1958 and had been fired from his teaching job in March 1968 after allegations of sexual misconduct with students. He was generally well-regarded by those who knew him, but he was also described as "fixated on young children and angry at women". Allen was interviewed by the police in 1971. Zodiac would not write again until 1974.[141] In September 1972, the SFPD obtained a search warrant for Allen's residence.[142] In 1974, Allen was arrested for sexually assaulting a 12-year-old boy;[143] he pleaded guilty and served two years' imprisonment.

Vallejo police served another search warrant at Allen's residence in February 1991.[144] Two days after Allen's death in 1992, Vallejo police served another warrant and seized property from his residence.[145] In July 1992, victim Mike Mageau identified Allen as the man who shot him in 1969 from a photo line-up, saying "That's him! It's the man who shot me!"[146][147] However, police officer Donald Fouke, who is speculated to have seen the Zodiac fleeing from the Stine killing, said in the 2007 documentary His Name Was Arthur Leigh Allen that Allen weighed about 100 pounds more than the man he saw, adding that his face was "too round". Nancy Slover, who received the call from the Zodiac in the aftermath of the Mageau/Ferrin shooting, said that Allen did not sound like the man on the phone.[148]

Other evidence existed against Allen, albeit entirely circumstantial. A letter sent to the Riverside Police Department from Bates' killer was typed with a Royal typewriter with an Elite type, the same brand found during the February 1991 search of Allen's residence. Allen owned and wore a Zodiac brand wristwatch. He also lived in Vallejo and worked minutes away from where one of the Zodiac victims (Ferrin) resided and from where one of the killings took place.[35]

In 2002, the SFPD developed a partial DNA profile from the saliva on stamps and envelopes of Zodiac's letters. The SFPD compared this partial DNA to that of Allen.[149][150] A DNA comparison was also made with the DNA of Don Cheney, who was Allen's former close friend and the first person to suggest Allen may be the Zodiac. Since neither test result indicated a match, Allen and Cheney were excluded as the contributors of the DNA.[151] Retired police handwriting expert Lloyd Cunningham, who worked on the Zodiac case for decades, stated, "They gave me banana boxes full of Allen's writing, and none of his writing even came close to the Zodiac. Nor did DNA extracted from the envelopes [on the Zodiac letters] come close to Arthur Leigh Allen."[4]

Gary Francis Poste

In October 2021, the Case Breakers, claiming to be a team of over forty former law enforcement investigators, military intelligence officers, and journalists, claimed to have identified the Zodiac as Gary Francis Poste, who died in 2018 at the age of 80. The team claimed to have uncovered forensic evidence and photos from Poste's darkroom, noting that scars on Poste's forehead matched those they said were described on the killer. They also claimed that removing the letters of Poste's name from one of Zodiac's cryptograms revealed an alternate message.[152]

The FBI subsequently stated that the case remained open and that there was "no new information to report", while local law enforcement expressed skepticism to the Chronicle regarding the team's findings.[153] Riverside police officer Ryan Railsback said the Case Breakers' claims largely relied on circumstantial evidence,[3][154] and author Tom Voigt, a Zodiac investigator, called the claims "bullshit," noting that no witnesses in the case described the Zodiac as having scars on his forehead.[155]

Poste has been investigated as a suspect in the case since at least 2014 by TV news anchor Dale Julin,[156] who claims he used anagrams to find a possible burial site for Donna Lass.[157] Poste is also one of the only few suspects to have been interviewed by authorities in the original Zodiac investigation.[158]

There are a few alleged connections to Poste and some Zodiac letters, such as in the 1974 "Exorcist" letter where the Zodiac gave himself a score of 37; Poste was born in 1937,[159] and would turn thirty-seven years old later that year in November. The Z-340 cipher was received on Poste's birthday in 1969. Another letter was received the very next day, the only time two letters were mailed back-to-back. Zodiac sent the Stine letter on the ninth anniversary of Poste being shot by a police officer, and Zodiac claimed to have talked to two officers on the night of Stine's murder.[160]

Other suspects

- In 2022, novelist Jarrett Kobek published How to Find Zodiac, in which Kobek named Paul Doerr as a suspect. Doerr was a North Bay resident with a post office box in Vallejo, where the first murders took place. Born in 1927, Doerr's age in 1969 (42) as well as his height (5' 9") was consistent with witness estimates. He was an avid fanzine publisher and letter-writer throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and many of his writings exhibit circumstantial parallels with the Zodiac. For example, Doerr was interested in cryptography; in Doerr's own Tolkien fanzine HOBBITALIA, he published a cipher in Cirth three days after Zodiac sent the Z13 cipher (Kobek in fact argues that the solution to the HOBBITALIA cipher is one of only three possible solutions to Z13). In Doerr's own fanzine PIONEER, he references the same formula for an ANFO bomb given later by the Zodiac, which Kobek argues was not widely known before the internet and the publication of The Anarchist Cookbook in 1971. In a letter to a different fanzine in 1970, Doerr advocated using solely 1¢ stamps to spite the U.S. Post Office, a practice the Zodiac employed on some of his letters. Doerr hinted in a 1974 letter to fanzine GREEN EGG that he had previously killed people and revealed in a different letter that he knew that mail to the Examiner would be delivered without a street address, just as the Zodiac sent them. Doerr's daughter read Kobek's book with the intent of suing for libel, but came away impressed with Kobek's research, adding in interviews that Doerr had at times been a violent and abusive father.[161] Paul Haynes, a researcher for I'll Be Gone in the Dark, called Doerr "the best Zodiac suspect that's ever surfaced".[162]

- In 2018, an independent inquiry by Italian journalist Francesco Amicone implicated Joseph "Giuseppe" Bevilacqua, a former superintendent of the Florence American Cemetery and Memorial, as a suspect in both the Zodiac and Monster of Florence (Il Mostro) cases.[163][164] Bevilacqua testified at the trial of Il Mostro suspect Pietro Pacciani in 1994.[165] Amicone alleged that on September 11, 2017, Bevilacqua confessed to being the killer in both cases.[166] Investigations by Italian authorities into Bevilacqua were suspended in 2021.[167]

- In 2009, an episode of the History Channel television series MysteryQuest investigated newspaper editor Richard Gaikowski. At the time of the murders, Gaikowski worked for Good Times, a San Francisco counterculture newspaper. His appearance resembled the Stine composite sketch, and Nancy Slover, the Vallejo police dispatcher who was contacted by the Zodiac shortly after the Blue Rock Springs attack, identified a recording of Gaikowski's voice as being the same as the Zodiac's.[168]

- Retired police detective Steve Hodel argues in his book The Black Dahlia Avenger that his father, George Hodel, was the perpetrator in the 1947 Black Dahlia case.[169] In a follow-up book, Hodel argued a circumstantial case that his father was also the Zodiac based upon a police sketch and the similarity of the style of the Zodiac letters to correspondence and handwriting from the unidentified suspect in the Dahlia case.[170]

- Kathleen Johns, who claimed to have been abducted by the Zodiac, picked out Lawrence Kane (also known as Lawrence Kaye) in a photo lineup. Patrol officer Don Fouke, who possibly observed the Zodiac following the Stine shooting, said that Kane closely resembled the man he and Eric Zelms had observed walking from the scene. Kane also worked at the same Nevada hotel as possible Zodiac victim Donna Lass. Kane, who was diagnosed with impulse-control disorder after suffering brain injuries in a 1962 accident, was previously arrested for voyeurism and prowling.[171] Fayçal Ziraoui, a French-Moroccan business consultant, claimed in 2021 that he solved the Z13 cipher and the solution to the puzzle reads, "My name is Kayr", which he said is a likely typo for Kaye. Others disputed that Ziraoui could have solved the cipher.[172]

- Police informants accused Richard Marshall, a silent film enthusiast, of being the Zodiac Killer, claiming that he privately hinted at being a murderer. Marshall lived in Riverside in 1966 and San Francisco in 1969, close to the scenes of the Bates and Stine murders. Marshall also hosted a screening of Segundo de Chomón's The Red Phantom (1907), a name used by the author of a possible 1974 Zodiac letter. Detective Ken Narlow said that "Marshall makes good reading but [is] not a very good suspect in my estimation."[171]

- In February 2014, it was reported that Louis Joseph Myers had confessed to a friend in 2001 that he was the Zodiac after learning that he was dying from cirrhosis of the liver. He requested that his friend, Randy Kenney, go to the police upon his death. Myers died in 2002, but Kenney allegedly had difficulties getting officers to take the claims seriously. There are several potential connections between Myers and the Zodiac; Myers attended the same high schools as victims Farraday and Jensen, and allegedly worked in the same restaurant as victim Ferrin. Between 1971 and 1973, when no Zodiac letters were received, Myers was stationed overseas with the military. Kenney says that Myers confessed he targeted couples because he had had a bad breakup with a girlfriend. While officers associated with the case are skeptical, they believe the story is credible enough to investigate if Kenney could produce credible evidence.[173]

- Robert Ivan Nichols, also known as Joseph Newton Chandler III, was a formerly unidentified identity thief who committed suicide in Eastlake, Ohio, in July 2002. After his death, investigators were unable to locate his family and discovered that he had stolen the identity of an eight-year-old boy who was killed in a car crash in Texas in 1945. The lengths to which Nichols went to hide his identity led to speculation that he was a violent fugitive. The United States Marshals Service announced his identification at a press conference in Cleveland on June 21, 2018. Some online sleuths suggested that he might have been the Zodiac, as he resembled police sketches and had lived in California.[174][175][176]

- Ross Sullivan became a person of interest through the possible link between the Zodiac and the Bates murder. Sullivan was a library assistant at Riverside City College and was suspected by coworkers after he had gone missing for several days following the murder. Sullivan resembled sketches of the Zodiac and wore military-style boots with footprints like those found at the Lake Berryessa crime scene. Sullivan was also hospitalized multiple times for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.[171]

- In 2007, Dennis Kaufman claimed that his stepfather, Jack Tarrance, was the Zodiac.[35] Kaufman turned several items over to the FBI, including a hood similar to the one worn by the Zodiac. According to news sources, DNA analysis conducted by the FBI on the items was deemed inconclusive in 2010.[177]

- Former California Highway Patrol officer Lyndon Lafferty said the Zodiac was a 91-year-old Solano County resident he referred to by the pseudonym "George Russell Tucker".[178] Using a group of retired law enforcement officers called the Mandamus Seven, Lafferty discovered Tucker and outlined an alleged cover-up for why he was not pursued.[179] Tucker died in February 2012 and was not named because he was not considered a suspect by police.[180]

- In 2014, Gary Stewart and Susan Mustafa published a book, The Most Dangerous Animal of All: Searching for My Father... and Finding the Zodiac Killer, in which Stewart claimed his search for his biological father, Earl Van Best Jr., led him to conclude Van Best was the Zodiac. In 2020, the book was adapted for FX Network as a documentary series.[181] Stewart based his theory on circumstantial evidence, including a police sketch resembling Van Best, partial fingerprint and handwriting matches, encrypted messages in Zodiac letters, and partial DNA connections. To validate Stewart's claims, the producers enlisted private investigator Zach Fechheimer, who uncovered that Stewart had manipulated a police report and traced Van Best Jr.'s presence in Europe during the Zodiac's activities. Additionally, experts discredited the DNA analysis and the handwriting and fingerprint matches. The producers chose to withhold their findings until near the end of the year-long production to minimize their impact on both the series and Stewart. Six months after production, director Kief Davidson stated that he thought Stewart's father was not the Zodiac, while executive producer Ross Dinerstein remained uncertain about Van Best Jr.'s potential involvement. Vulture asserted that despite the absence of substantiated evidence linking Van Best to the Zodiac, "he was, without a doubt, a pedophile who impregnated a teenager and then abandoned their newborn son in a stairwell."[182]

Unnamed suspects

- In his 1976 autobiography My Life On Trial, Melvin Belli described an engineered encounter with himself, undercover police officers, and an unnamed Riverside law student who had allegedly threatened a female classmate by claiming to be the Zodiac.[183] Upon meeting the young man face-to-face and confronting him, Belli decided that he was not the Zodiac and subsequent handwriting analyses remained inconclusive. Authorities ruled this person out as a suspect.

- In 2009, former lawyer Robert Tarbox, who was disbarred in August 1975 by the California Supreme Court for failure to pay clients,[184][185] said that in the early 1970s a merchant mariner walked into his office and confessed to him that he was the Zodiac. The seemingly lucid seaman, whose name Tarbox would not reveal based on confidentiality, described his crimes briefly but persuasively enough to convince Tarbox. The man said he was trying to stop himself from his "opportunistic" murder spree but never returned to see Tarbox again. Tarbox took out a full-page ad in the Vallejo Times-Herald that he claimed would clear the name of Arthur Leigh Allen as the killer, his only reason for revealing the story thirty years after the fact. Graysmith said Tarbox's story was "entirely plausible".

- In 2010, a picture surfaced of known Zodiac victim Darlene Ferrin and an unknown man who closely resembles the composite sketch, formed based on eyewitnesses' descriptions of the Zodiac. According to America's Most Wanted (February 19, 2011), police believe the photo was taken in San Francisco in either 1966 or 1967.[186] A documentary released in 2023, titled Myth of the Zodiac Killer, features a segment where this photo is reexamined; it's possible the man in the photo is either Ferrin's ex-husband or a doctor who previously worked with her.

- Sandy Betts is an amateur Zodiac researcher who claims that the people responsible for the Zodiac attacks repeatedly harassed and attacked her.[187][188][189] She states that three men were the primary culprits and that at least one of these core members is identified and still lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.[190] Betts also claims that the primary killer was known as "Tony" and worked in construction. She estimates several dozen fatal Zodiac attacks overall. In her narrative, some elements of Zodiac crimes are theatrical in nature.

Cleared suspects

- According to researcher Tom Voigt, fingerprint comparison in February 1989 eliminated serial killer Ted Bundy as a person of interest in the Zodiac case.[191]

- Serial killer Edward Edwards, who committed five murders between 1977 and 1996, was linked to the Zodiac murders and several other unsolved cases by former cold case detective John A. Cameron. Cameron tied Edwards to the West Memphis Three, the Atlanta Child Murders, the 2001 Amerithrax attacks, the killing of Chandra Levy and the murder of Kent Heitholt. He also documented similarities between the murder of JonBenét Ramsey and the Zodiac's known crimes. The fake "ransom note" contained Zodiac-like misspellings and references to crime films, including Dirty Harry (1971), which the Zodiac referenced in his correspondence.[192] Cameron also wrote that JonBenét told a neighbor that she would meet "Santa Clause" on the night that she was later killed.[193] The Zodiac wore an elaborate costume at Lake Berryessa and claimed to use disguises when he committed his crimes. However, Cameron's theories were met with "almost universal disdain, especially from law enforcement".[194]

- Ted Kaczynski, a domestic terrorist and mathematician also known as the Unabomber, was investigated for possible connections to the Zodiac in 1996. Kaczynski worked in northern California at the time of the murders and, like the Zodiac, had an interest in cryptography and threatened the press into publishing his communications.[195] Kaczynski was ruled out by both the FBI and SFPD based on fingerprint and handwriting comparisons, and by his absence from California on certain dates of known Zodiac activity.[196]

- The Manson Family: following the capture of Charles Manson and his murderous cult, a 1970 report by the California Bureau of Criminal Identification and Investigation stated that all male members of the Manson Family had been investigated and eliminated as Zodiac suspects.[196]

Letters and ciphers gallery

Zodiac's letter sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on July 31, 1969

Zodiac's letter sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on July 31, 1969 The decryption of the July 31, 1969 408-cipher by Donald and Bettye Harden

The decryption of the July 31, 1969 408-cipher by Donald and Bettye Harden Zodiac's letter sent to the Vallejo Times-Herald on July 31, 1969

Zodiac's letter sent to the Vallejo Times-Herald on July 31, 1969 Zodiac's letter sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on November 8, 1969 with the 340 cipher, which was decrypted on December 5, 2020

Zodiac's letter sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on November 8, 1969 with the 340 cipher, which was decrypted on December 5, 2020 Zodiac's letter sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on April 20, 1970

Zodiac's letter sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on April 20, 1970 Zodiac's bomb schematic sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on April 20, 1970

Zodiac's bomb schematic sent to the San Francisco Chronicle on April 20, 1970

In popular culture

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Well into the 1970s, the Zodiac wrote letters claiming responsibility for earlier and later killings, but he has never been definitively linked to any crime that took place before 1968 or after 1969.

- ↑ The killer himself used the name the Zodiac and is often simply called Zodiac.

- ↑ When corrected for most errors, excluding the distinctive spelling of paradice, the Z408 message says:

I like killing people because it is so much fun. It is more fun than killing wild game in the forest because man is the most dangerous animal of all. To kill something gives me the most thrilling experience. It is even better than getting your rocks off with a girl. The best part of it is that when I die, I will be reborn in paradice and all that I have killed will become my slaves. I will not give you my name because you will try to slow down or stop my collection of slaves for my afterlife. ebeorietemethhpiti

- ↑ Shortly after the decoding of this cipher, Vallejo police contacted a psychiatrist based at the state prison at Vacaville to review the contents. This expert determined the contents were typical of a brooding and isolated individual; the psychiatrist interpreted the author's comparison of the thrill of murder to the satisfaction of sex as "usually an expression of inadequacy" from a male who senses extreme rejection. The fact that the author claimed to be collecting slaves for his afterlife revealed this individual's sense of omnipotence.[19]

- ↑ In 1976, Toschi would opine his belief to a reporter from the Fort Scott Tribune that the Zodiac lived in the San Francisco Bay area, and that the letters he had sent had been an "ego game" for him, adding: "He's a weekend killer. Why can't he get away Monday through Thursday? Does his job keep him close to home? I would speculate he maybe has a menial job, is well thought of and blends into the crowd ... I think he's quite intelligent and better educated than someone who misspells words as frequently as he does in his letters."[34]

- ↑ When corrected for most errors, excluding the distinctive spelling of paradice, the Z340 message says:

I hope you are having lots of fun in trying to catch me. That wasn't me on the TV show, which brings up a point about me. I am not afraid of the gas chamber because it will send me to paradice all the sooner, because I now have enough slaves to work for me where everyone else has nothing when they reach paradice, so they are afraid of death. I am not afraid because I know that my new life is life will be an easy one in paradice death.

References

Citations

- ↑ "Zodiac Killer – Crimes, Letters, Codes, DNA". ZodiacKiller.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Zodiac '340 Cipher' cracked by code experts 51 years after it was sent to the S.F. Chronicle". San Francisco Chronicle. December 11, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- 1 2 Fagan, Kevin (October 6, 2021). "Zodiac Killer case solved? Case Breakers group makes an ID, but police say it doesn't hold up". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- 1 2 Williams, Lance (July 19, 2009), "Another possible Zodiac suspect put forth", San Francisco Chronicle, archived from the original on July 27, 2010

- ↑ SFPD News Release, March 2007

- 1 2 Russo, Charles (March 2007). "Zodiac: The killer who will not die". San Francisco. San Francisco, California: Modern Luxury. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011.

- ↑ Napa PD Website, Vallejo PD Website and "Tipline", Solano County Sheriff's Office

- ↑ California Department of Justice Website

- ↑ "Dec. 20, 1968 – Lake Herman Road". Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (1976). Zodiac. Berkley. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-425-09808-0.

- ↑ Graysmith, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ Graysmith, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Graysmith, p. 29.

- 1 2 Graysmith, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ "The Tuscaloosa News: Zodiac the Killer". The Tuscaloosa News. October 27, 1969. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ Graysmith, p. 49.

- ↑ "Coded Clues in Murders". San Francisco Chronicle, August 2, 1969. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Graysmith, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ "Zodiac the Killer". The Tuscaloosa News. October 17, 1969. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ True Crime: Unsolved Crimes ISBN 0-7835-0012-2 p. 20

- ↑ "Zodiac the Killer". The Tuscaloosa News. October 27, 1969. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Definite Zodiac Victims Cecelia Shepard and Bryan Hartnell".

- 1 2 Graysmith, pp. 62–77

- 1 2 "Message written on Hartnell's car door". Zodiackiller.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ↑ True Crime: Unsolved Crimes ISBN 0-7835-0012-2 p. 21

- ↑ Stanley, Pat (February 18, 2007). "Zodiac on the line ...". Napa Valley Register. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ↑ Dorgan, Marsha (February 18, 2007). "Online exclusive: In the wake, of the Zodiac". Napa Valley Register. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ↑ Carson, L. Pierce (February 18, 2007). "Zodiac victim: 'I refused to die'". Napa Valley Register. Archived from the original on September 22, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ↑ "Girl Dies of Stabbing at Berryessa" (PDF). San Francisco Chronicle. September 30, 1969. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ↑ Dorgan, Marsha (February 18, 2007). "Tracking the mark of the Zodiac for decades". Napa Valley Register. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Definite Zodiac Victim Paul Stine". Zodiackiller.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ Rodelli, Mike (2005). "4th Interview with Don Fouke – Thoughts on the Zodiac Killer". Mike Rodelli. Archived from the original on May 1, 2006. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ↑ True Crime: Unsolved Crimes ISBN 0-7835-0012-2 p. 27

- ↑ "Lone Officer Continues Search for Zodiac". The Fort Scott Tribune. September 15, 1976. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Zodiac Killer: Meet The Prime Suspects". America's Most Wanted. Archived from the original on September 1, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ Let's Crack Zodiac - Episode 5 - The 340 Is Solved!. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Call to Chat Show".

- ↑ True Crime: Unsolved Crimes. Time-Life Books. 1993. p. 32. ISBN 0-783-50012-2.

- ↑ McCarthy, Chris. "Alphabet of the 340 Character Zodiac Cypher". Archived from the original on February 6, 2008.

- ↑ Canon, Gabrielle (December 11, 2020). "Zodiac: cipher from California serial killer solved after 51 years". The Guardian. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ↑ Ong, Danielle (December 19, 2020). "Identity of 'Zodiac Killer' That Terrorized San Francisco Remains a Mystery". The San Francisco Times. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ↑ ""I've Killed Seven" The Zodiac Claims" (PDF). San Francisco Chronicle. November 12, 1969. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2012.

- ↑ "New Letters From Zodiac – Boast of More Killings" (PDF). San Francisco Chronicle. November 12, 1969. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2012.

- ↑ Foreman, Laura, ed. (1993). True Crime: Unsolved Crimes. New York City: Time Life Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7835-0012-6.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (1986). Zodiac (Berkley mass-market tie-in edition, 2007 ed.). NY, USA: Berkley. pp. 308–311. ISBN 9780425212189.

- ↑ Lothspeich, Jennifer (February 4, 2020). "Police looking into claims by historian that Zodiac Killer may be responsible for 1962 Oceanside murder". KFMB-TV. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020.

- ↑ Staahl, Derek (February 3, 2020). "Did the Zodiac kill in Oceanside? Police re-test evidence in cold case". KGTV.

- ↑ Harrison, Ken. "The Oceanside Zodiac murder". The San Diego Reader.

- ↑ Lombardo, Delinda. "Was the Zodiac killer in San Diego?". The San Diego Reader.

- ↑ "The Zodiac Killer: The Crimes". crimeandinvestigation.co.uk. January 31, 2013. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ↑ "Murdered but Not Forgotten: Were They Victims of Zodiac Killer?". Santa Barbara Independent. June 2, 2011. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Did the Zodiac killer murder an Alabama couple in 1964?". Alabama.com. October 22, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ "The Zodiac Killer's Forgotten Victims?". ZodiacRevisited.com. April 16, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Murdered but Not Forgotten: Were They Victims of Zodiac Killer?". Santa Barbara Independent. June 2, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Officer Richard Radetich". Officer Down Memorial Page. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- 1 2 Graysmith, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Photo of watch found near Bates' body. Archived February 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ↑ Graysmith, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Graysmith, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ True Crime: Unsolved Crimes ISBN 0-7835-0012-2 pp. 6–7

- ↑ "Riverside Police Department Homicide Cold Case Unit. Spotlighted Case: Cheri Jo Bates". Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ↑ Wark, Jake M. "Paul Avery and the Riverside Connection". AOL. Archived from the original on November 10, 2006.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Janet. New movie 'Zodiac' includes Redlands resident's attack Archived February 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Riverside Press-Enterprise, March 1, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2007.

- ↑ Smith, Dave (November 16, 1970). "Evidence Links Zodiac Killer to '66 Death of Riverside Coed". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Kathleen Johns -- the Quester Files Zodiac Killer Investigation".

- 1 2 3 "Police report". Zodiackiller.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- 1 2 Montaldo, Charles. "The Zodiac Killer Continued – The Zodiac Letters". About.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008.

- ↑ Adams, p. 268.

- ↑ Graysmith, p. 139.

- ↑ Adams, p. 274

- ↑ "Spearch for Zodiac Victim in Mountain Area". The Bulletin. March 27, 1971. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- 1 2 True Crime: Unsolved Crimes ISBN 0-7835-0012-2 p. 43

- ↑ Graysmith, p. 178.

- ↑ Dowd, Katie (December 28, 2023). "Missing Tahoe casino nurse Donna Lass finally identified". SFGATE. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (1986). Zodiac (Berkley mass-market movie tie-in edition/2007 ed.). USA: Berkley/Random House. p. 309. ISBN 9780425212189.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (1986). Zodiac (Berkley mass-market movie tie-in edition/2007 ed.). USA: Berkley/Random House. p. 311. ISBN 9780425212189.

- ↑ "ELAINE DAVIS, KIDNAPPING AND HOMICIDE (1969)". Walnut Creek Police Department.

- ↑ Goodyear, Charlie (May 16, 2001). "Body of girl missing since '69 identified". SFGate. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ Contra Costa Times (newspaper), December 30, 1969, page 1.

- ↑ Concord Transcript (newspaper), January 15, 1970, page 2.

- ↑ "THE MURDER OF LEONA LARELL ROBERTS". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ "THE MURDER OF PATRICIA KING". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ "After 46 Years, Bride-to-Be Murders Remain Unsolved". FOX40. October 6, 2016.

- ↑ "THE MURDER OF JUDITH HAKARI". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ Napa Valley Register (newspaper), March 25, 1970, page 2.

- ↑ Napa Valley Register (newspaper), April 15, 1970, page 15)

- ↑ "THE MURDER OF CAROL BETH HILBURN". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ "THE DISAPPEARANCE OF DENISE ANDERSON". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ "Denise Kathleen Anderson". The Charley Project.

- ↑ "THE MURDER OF SUSAN MARIE LYNCH". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ "Authorities take new look at 50-year-old Coastside killing that still shocks conscience". Half Moon Bay Review. March 29, 2022.

- ↑ "THE FINAL DAY". Zodiac Ciphers.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (2007). Zodiac Unmasked. Penguin. p. 163. ISBN 9780425212738.

- ↑ "Zodiac Killer : The Letters - 01-29-1974". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (2007). Zodiac. Berkley Books. p. 252. ISBN 9780425212189.

- ↑ "Zodiac Killer: The Letters - 11-09-1969". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Weiss, Mike (October 15, 2002). "DNA seems to clear only Zodiac suspect / new-found evidence may allow genetic profile of '60s killer". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Affidavit For Search Warrant - 2963 Santa Rosa Avenue, space A-7 (14 September 1972)" (PDF). San Francisco Police Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- 1 2 Sieh, Cat (March 1, 2007). "Former Calaveras teacher was 'Zodiac' suspect". The Union Democrat. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Graysmith, Robert (2007). Zodiac Unmasked. Penguin. p. 118. ISBN 9781440678127.

- ↑ "Sonoma County Sheriff's Office - Arthur Leigh Allen Arrest Report (30 September 1974)". Sonoma County Sheriff's Office. p. 5. Retrieved March 17, 2013.