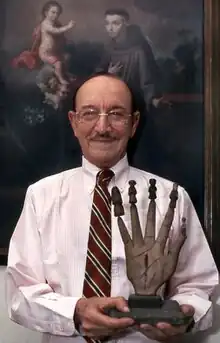

Teodoro Vidal Santoni (1923–2016) was a Puerto Rican government official, art historian, and folklorist who collected Puerto Rican art. His donation of objects to the Smithsonian Institution in 1997 remains the largest donation from a single donor.[1][2]

Biography

Teodoro Vidal was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1923 to Teodoro Vidal Sánchez and Lucila Santoni. His father was originally from Fajardo and his mother from Ponce. He attended the New York Military Academy and served in the United States Army and during the Korean War. In 1953, he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a master's degree in business. He immediately went into public service as an assistant to Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. He served as chief of protocol at La Fortaleza, as a military advisor, and in cultural affairs.[3]

During his tenure in government, Vidal worked on historic preservation at La Fortaleza and served as a founding member of the board of directors for the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña. When Muñoz Marín retired in 1964, Vidal committed solely to working on Puerto Rico's cultural heritage through independent research, publishing, and collecting. He was honored throughout his lifetime in both Puerto Rico and in mainland United States for his work on the island's folk art. He died on January 16, 2016, in San Juan, Puerto Rico at the age of 92.[4]

Collector

Vidal began collecting Puerto Rican art one day when he was on his way to La Fortaleza and saw storefronts on the Calle del Cristo that were selling sculpted saints and other folkloric objects. His collection began with objects of this sort including furniture, masks, canes, tools, instruments, textiles, woodworking, and other decorative objects. He also collected fine art, including important paintings by José Campeche. He hoped that one day Puerto Rico would have a national museum for its art and traditions.[5]

By the early 1990s, his collection amounted to over 6,000 objects and he began to look for an institution that would be willing to house the collection. He believed the objects would begin to deteriorate if he did not find a suitable preservation solution for them.[5] He initially tried to keep the objects on the island, looking for local institutions that would take his collection. In 1996 Marvette Pérez, a curator from the National Museum of American History, offered to take the entire collection on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution. About 4,000 objects from Vidal's collection were shipped and officially donated to the Smithsonian in 1997. This gift is the largest donation by a single individual to the National Museum of American History to date. Objects from Vidal's collection were featured in a 1997–2000 exhibition titled Puerto Rico: A Collector’s Vision. Some of the objects are installed in the permanent collection displays of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Museum of American History.[1][6][7][8] In his book The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States, scholar Jorge Duany has carefully analyzed this collection, its relationship to Vidal, and its exhibition.[9]

The remaining objects from Vidal's collection that were left behind on the island were donated to the Luis Muñoz Marín Foundation. This included around 1,500 objects. Many of objects are on display in the foundation's center in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[10]

Scholar

In addition to collecting Puerto Rican art, Vidal also wrote numerous books and articles about the subject. He was considered an expert on José Campeche, as well as santo and other folkloric traditions on the island. He also studied the oral traditions, literature, and spirituality of Puerto Rico.[5]

Publications

- La Fortaleza, o Palacio de Santa Catalina. (San Juan, 1964.) OCLC 78102697

- Los milagros en metal y en cera de Puerto Rico. (Photographs by Pablo Delano. San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1974.) ISBN 0960071415

- Santeros puertorriqueños. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1979.) ISBN 0960071423

- Las caretas de cartón del Carnaval de Ponce. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1982.) ISBN 0960071431

- San Blas en la tradición puertorriqueña. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1986.) ISBN 0960071474

- Las caretas de los vejigantes ponceños: modo de hacerlas. (San Juan, 1988.) OCLC 30360301

- Tres retratos pintados por Campeche. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1988.) ISBN 0960071458

- Tradiciones en la brujería puertorriqueña. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1989.) OCLC 21484316

- Los Espada: escultores sangermeños. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 1994.) OCLC 31496176

- Cuatro puertorriqueñas por Campeche. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2000.) ISBN 9780960071463

- La bruja puertorriqueña. (2002)

- La Monserrate negra con el niño blanco: una modalidad iconográfica puertorriqueña. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2003.) ISBN 9781596086838

- El vejigante ponceño. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2003.) OCLC 52789734

- José Campeche: portrait painter of an epoch. (2004)

- José Campeche: retratista de una época. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2005.) OCLC 65193060

- Los reyes magos: tradición y presencia. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2005.) OCLC 63256749

- El caballo en la obra de Campeche. (San Juan: Museo de las Américas, 2006.) OCLC 170968557

- Escultura religiosa puertorriqueña. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2006.) ISBN 096007144X

- El control de la naturaleza mediante la palabra en la tradición. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2008.) ISBN 1596084898

- Oraciones romancísticas. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2009.) ISBN 9781596087248

- Oraciones, conjuros y ensalmos en la cultura popular puertorriqueña. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2010.) ISBN 9781596086838

- Cuatro campeches de regreso en Puerto Rico. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2011.) OCLC 782127340

- El Museo Nacional de Artes y Tradiciones Puertorriqueñas (2012)

- Pinturas y esculturas puertorriqueñas antiguas. (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2015.) ISBN 9781618877161

- El arte de la miniatura en Puerto Rico (San Juan: Ediciones Alba, 2015.) ISBN 9781618875310[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 Velasquez, L. Stephen. "The Teodoro Vidal Collection: Creating Space for Latinos at the National Museum of American History". The Public Historian. 23 (4): 113–124 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Kaplan, Howard (February 10, 2016). "We Remember Collector Teodoro Vidal". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ↑ Figueroa, Evelyn. "Teodoro Vidal Santoni – Notable Folklorists of Color". notablefolkloristsofcolor.org. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Teodoro Vidal Santoni – Personas – eMuseum". museocoleccion.uprrp.edu. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Robiou Lamarche, Sebastián (January 22, 2016). "Teodoro Vidal Santoni (1923–2016): la trayectoria de un coleccionista". 80 Grados. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Teodoro Vidal Collection of Puerto Rican History: About the Collection". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ↑ Tsang, Jia-sun. A Closer Look: Santos from Puerto Rico: Santos from the Vidal Collection, National Museum of American History. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, 1998. OCLC 80687167

- ↑ Burchard, Hank. "Puerto Rico's Bright Vision." Washington Post, September 4, 1998. Accessed 2023-07-21.

- ↑ Duany, Jorge. "Collecting the Nation: The Public Representation of Puerto Rico's Cultural Identity." In The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States, pp. 137-65. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. ISBN 9780807861479

- ↑ Quirós Alcalá, Julio E. "Teodoro Vidal – FLMM PDI". luismunozmarin.org. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ↑ "teodoro vidal - Search Results". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved May 15, 2023.