| Taymouth Hours | |

|---|---|

| British Library | |

| |

| Also known as | Yates Thompson MS 13 |

| Type | Book of Hours |

| Date | 1325-1335 |

| Language(s) | Anglo-Norman French and Latin |

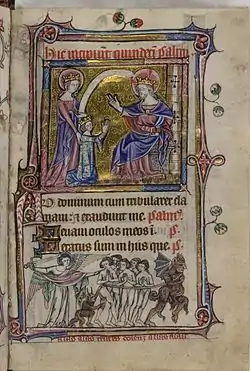

The Taymouth Hours (Yates Thompson MS 13) is an illuminated Book of Hours produced in England in about 1325–35. It is named after Taymouth Castle where it was kept after being acquired by an Earl of Breadalbane in the seventeenth or eighteenth century.[1] The manuscript's shelf mark originates from its previous owner, Henry Yates Thompson, who owned an extensive collection of illuminated medieval manuscripts which he sold or donated posthumously to the British Library.[2] The Taymouth Hours is now held by the British Library Department of Manuscripts in the Yates Thompson collection.[2]

Most pages have a bas-de-page illustration, often accompanied by a caption in Anglo-Norman French or Latin. A few have bilingual captions that include Middle English.[3] During this period in Medieval England, Anglo-Norman would have been the language most commonly spoken by affluent and royal families.[4] The illustrations include both sacred and secular scenes. Picture-narratives of the stories of Bevis of Hampton (ff. 8v–12) and Guy of Warwick (ff. 12v–17) appear at the beginning of the text, while below the Matins of the Hours of the Virgin (ff. 60v–67v) are fifteen scenes depicting a tale of a damsel captured by a wild man.[5]

History

Possible Patrons/Intended Owners

There have been numerous attempts to identify the book's patron and original intended owner. It has been speculated that the patron and destinee was Isabella of France, wife of Edward II, or that the book may have been made for one of their daughters, Joan of the Tower.[6] Other scholars have speculated that Philippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III, son of Isabella and Edward II, was the original intended owner.[6] Illustrations of a crowned woman are featured on four different pages of the book (ff. 7r, 18r, 118v, and 139r), serving as the initial indication of a royal patron and/or recipient.[1] The quality of illustrations and impressive materials such as gold leaf also point to an aristocratic patronage.[2] The Taymouth Hours is one of two English books of hours made between 1240 and 1350 with links to royal patronage; thus it exemplifies a higher level of craftsmanship compared to other books of hours assumed to have been owned by affluent, secular individuals.[6] The most puzzling piece of the question of patronage and intended ownership is the inclusion of two illustrations that depict crowned women kneeling in prayer, each with a male companion: one of the men is bare-headed while the other wears a crown.[6]

Isabella of France

Previous scholarship has traditionally hypothesised that Isabella of France was the patron due, in part, to evidence of or arguments for her ownership and patronage of various other illuminated manuscripts.[6] The proposed dating of the book falls within Isabella's reign as Queen of England.

Philippa of Hainault

Kathryn Smith makes the case that Philippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III, was the patron of the Taymouth Hours, instead.[6] She argues that Philippa had the book made sometime c. 1331 not for herself, but rather as a "betrothal gift" for her sister-in-law, Eleanor of Woodstock.[6] In 1331, while still living at the English court, Eleanor was betrothed to Reginald II of Guelders.[6] Smith's hypothesis derives, in part, from her analysis of Philippa's relationship to Eleanor prior to her marriage to Reginald. Philippa had been Eleanor's guardian since 1328.[6] Eleanor's betrothal and marriage were arranged beginning in 1330 by her brother, Edward III, in an effort to advance his political connections to the Low Countries; the union also may have been aided by Philippa's mother, Jeanne de Valois, aka Joan of Valois, wife of William III, Count of Hainault.[6] Eleanor and Reginald were wed in May of 1332.[6] Smith also builds her hypothesis on analyses of the "portraits" in the manuscript, especially the crowned and wimpled woman wearing a translucent veil and the uncrowned man portrayed at Matins of the Holy Spirit (fol. 18r), figures which, Smith hypothesises, were intended to represent Eleanor of Woodstock and Reginald II of Guelders; and the crowned, wimpled woman and crowned man shown in the 'bas-de-page' at Matins of the Cross (fol. 118v); Smith suggests that these figures were meant to represent Philippa of Hainault and Edward III.

One of Smith's main textual sources is an entry in Philippa's Wardrobe Book of the Household from October 1331, which records a payment to the artist Richard of Oxford.[6] The entry notes Philippa's payment for two Books of Hours. Smith proposes that the Taymouth Hours might have been one of these books, and that this dated entry supports the theory that Philippa commissioned the Taymouth Hours as a "betrothal gift" for Eleanor. While Smith argues that the manuscript was intended for Eleanor, she maintains that it is "unknown" whether Eleanor "actually took possession of" it.[6]

Purpose

Books of hours were Christian devotional collections, usually containing psalms, prayers, and illustrations.[7][8] They resembled Psalters in form and function, but were condensed and personalised. The purpose of these books were to provide private owners with prayer materials, which could be read and recited during certain times of the day, month, season, and liturgical year.[9][7] Many of the patrons of books of hours held secular positions in society, and therefore had a need for individual prayer books to practice their faith at home.[7] As is the case of the Taymouth Hours, books of hours were customised to fit the aesthetic desires of the patron.[7] English books of hours have also been referred to by the term 'primers', taken from the Middle English word for books of hours.[9] This second name is exclusive to books of hours made in England, and has been exemplified in examples of books of hours, simpler, less ornate prayer collections, and children's religious literature.[9]

Typical of many other book of hours of the time period, the Taymouth hours contains a calendar, illustrations of the zodiac, the Latin offices, the Penitential Psalms, Gradual Psalms, the Litany of Saints, and the Office of the Dead.[6]

Illustrations

The pages of the book exemplify bas-de-page illustrations, meaning that the visual work is positioned at the bottom of the page and below a block of text.[1] 384 illustration scenes are featured in the lower margin of the book.[1] Kathryn Smith identifies the manuscript's use of a frame border made out of marginal illustrations as a design element derived from contemporary French illuminated manuscripts.[6] This illustrated border completely surrounds the text. The beginnings of the various devotional texts are presented to the reader by display pages with miniature marginal illustrations.[4]

.jpg.webp)

Marginal scenes with religious prayer text written in Anglo-Norman make up the body of secular illustrations in the Taymouth Hours. The story of Bevis of Hampton, the protagonist of an English verse romance tale, is transposed visually on the folio pages 8v to 12. Originally composed in the early thirteenth century in French, the tale of Bevis of Hampton was a popular Matter of England romance that has stood the test of time and is the only English verse romance that never had to be rediscovered. Another Matter of England romance character seen on folio pages 12v to 17 is Guy of Warwick, a figure who takes on a similar literary role such as Bevis of Hampton.[6] Both secular poems were extremely popular at the proposed time of construction of the Taymouth Hours, and have appeared in other manuscripts up until the early 16th century.[6] Kathryn Smith points to the inclusion of these popular Matter of England characters in the manuscript as suiting the idea of Eleanor of Woodstock as the book's original intended recipient, because Guy of Warwick and Bevis of Hampton were "quintessentially English" in their characterisation and could have served as a "comforting reminder of home" for Eleanor, had she ever received the manuscript and had she taken it with her to her adoptive land.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Detailed record for Yates Thompson 13 British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

- 1 2 3 Wormald, Francis (1951). "The Yates Thompson Manuscripts". British Museum Quarterly. 16. doi:10.2307/4422290. JSTOR 4422290.

- ↑ Brownrigg (1989)

- 1 2 Manion, Margaret (2014). "Review". Studies in Iconography. 35: 268–273 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Loomis (1917), 750-55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Smith, Kathryn (2012). The Taymouth Hours: Stories and the Construction of the Self in Late Medieval England. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Kathryn A. (2003). Art, Identity and Devotion in Fourteenth-Century England: Three Women and Their Books of Hours. London: The British Library. ISBN 9780712348300.

- ↑ Rudy, Kathryn (2016). Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized Their Manuscripts. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-2-8218-8397-0.

- 1 2 3 Kennedy, Kathleen E. (2014). "Reintroducing the English Book of Hours, or English "Primers"". Speculum. 89 (3): 693–723. doi:10.1017/S0038713414000773. JSTOR 43577033.

Sources

- Lord, Carla, and Carol Lewine. "Introduction: Secular Imagery in Medieval Art." Source: Notes in the History of Art, 33, no. 3/4, 2014. www.jstor.org/stable/23725944.

- Sandler, Lucy Freedman. "The Study of Marginal Imagery: Past, Present, and Future." Studies in Iconography 18, 1997. www.jstor.org/stable/23924068.

- Doyle, Maeve, Kinney, Dale, Armstrong, Grace, Easton, Martha, Hertel, Christiane, Perkinson, Stephen, and Walker, Alicia. The Portrait Potential: Gender, Identity, and Devotion in Manuscript Owner Portraits, 1230-1320, 2015, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Partner, Nancy F. Studying Medieval Women: Sex, Gender, Feminism. Cambridge, Mass.: Medieval Academy of America, 1993.

- Smith, Kathryn A. Art, Identity and Devotion in Fourteenth-Century England: Three Women and Their Books of Hours. London: The British Library, 2003.

- Runde, Emily. “The Taymouth Hours: Stories and the Construction of the Self in Late Medieval England.” Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval & Renaissance Studies 44 (September 2013): 336–39. doi:10.1353/cjm.2013.0054.

- Rudy, Kathryn M. Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized Their Manuscripts. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2016. Accessed March 25, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1g04zd3.

- "Front Matter." The British Museum Quarterly 16, no. 1 (1951): Iv. Accessed March 25, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4422287.

- Kennedy, Kathleen E. "Reintroducing the English Books of Hours, or "English Primers"." Speculum 89, no. 3 (2014): 693-723. Accessed March 25, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/43577033.

- Loomis, Roger Sherman. "A Phantom Tale of Female Ingratitude", Modern Philology, Volume 14, 1917, 750-55.

- Brownrigg, Linda. "The Taymouth Hours and the Romance of Bevis of Hampton." English Manuscript Studies 1100-1700, Volume 1, 1989, 222-41.

- Camille, Michael. Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. London: Reaktion Books, 1992. ISBN 9780948462283

- Brantley, Jessica. "Images of the Vernacular in the Taymouth Hours", in Decoration and Illustration in Medieval English Manuscripts, English Manuscript Studies 1100-1700, 10. London: British Library, 2002, pp. 83–113. ISBN 9780712347327

- Stanton, Anne Rudloff. "Turning the Pages: Marginal Narratives and Devotional Practice in Gothic Prayerbooks", in Blick, Sarah and Gelfand, Laura (eds). Push Me, Pull You: Imaginative and Emotional Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art. Leiden: Brill, 2011, pp. 75–122. ISBN 9789004205734

- Slater, Laura. "Queen Isabella of France and the Politics of the Taymouth Hours", Viator, Volume 43, 2012, 209-45.

- Turner, Marie. "Feeling Persecuted: Christians, Jews and Images of Violence in the Middle Ages". Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures, Volume 38, No. 1, 2012. 113-117.

- Smith, Kathryn. The Taymouth Hours: Stories and the Construction of Self in Late Medieval England. London: British Library, 2012. ISBN 9780712358699

External links

- British Library Digitised Manuscripts Digital facsimile of the entire manuscript