Swaylands is a private parkland estate set high upon the Kentish Weald, on the edge of the village of Penshurst in the Sevenoaks district of Kent, England.

The Estate is situated between the market town of Tonbridge and the spa town of Royal Tunbridge Wells, at the heart of an area of countryside between the neighbouring villages of Penshurst, Chiddingstone and Hever.

The three main apartment buildings on the Estate are, from north to south, Drummond Hall, Swaylands House and Woodgate Manor, which together fall within the Sevenoaks district. Drummond Hall and Woodgate Manor are relatively new buildings, whose architecture is inspired by the original house.

Situated wholly within the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the Estate comprises over forty acres of terraced gardens and grounds, featuring a rockery, a cricket pitch and its listed pavilion, a tennis court, a rose garden, a pond, a lake, waterfalls and a small landscape park, all of which were developed through the second half of the nineteenth century. Following years of deterioration in the late twentieth century, the gardens and buildings have now been restored.

History

The tithe map for 1840 shows there was a farm in the same place as the current house. It was called Workhouse Farm and belonged to the Penshurst Parish.[1]

William Woodgate, a local solicitor, and member of a prominent local family, bought the farm and 33 acres of land from the Penshurst Parish in 1835/36. This was eventually increased to 95 acres.

The original Swaylands house, a villa (below), was built from around 1837 for William Woodgate. Guttering boxes on the original villa are marked "1842", which indicates the date the house was likely completed. When William Woodgate built this three gabled villa on the top of the hill, it was described as a smaller version of his birthplace, Somerhill House, in Tonbridge. In 1842 William's aunt recorded in her diary “William Woodgate brought his family to his new house, the bells gave a merry peal as they passed through the village.” He arrived with his wife Harriet and children (of which there were eventually 12).

Edward Cropper came from Pembrokeshire to buy Swaylands from William Woodgate in 1859. By this time, William Woodgate had experienced financial difficulties, was suffering ill health and returned to his home in Cumberland Terrace, London. Mrs Frances Allnut, from the Grove, Penshurst, recorded on 6 August 1859 “The bells rang merrily for Mr and Mrs Cropper coming to Swaylands, having painted and prepared the house.”

In the 1870s Cropper employed the prominent Victorian architect[2] George Devey to extend greatly the house and to terrace the gardens. Also constructed was a stable block and lodge at the northern boundary of Penshurst Road.

Edward Cropper died in 1877 and, despite all the improvements he had made to Swaylands, his widow put the estate on the market and moved back to Pembrokeshire.

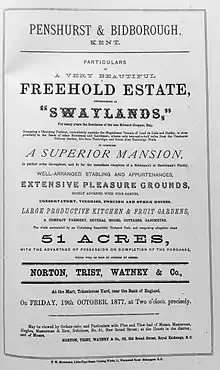

When the Swaylands estate was advertised in The Times by Norton, Trist, Watney & Co. in September 1877, the sale document described a very desirable property “in perfect order throughout, and fit for the immediate reception of a Nobleman's or Gentleman’s family”.

By this time it had a miniature gas works, vinery and specimen shrubs and trees, including a splendid Wellingtonia planted by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Only 51 acres are mentioned in this document although Edward Cropper paid parish rates on 261 acres.

Swaylands was purchased by the banker George James Drummond following an auction of "a superior mansion" at the Mart, Tokenhouse Yard, near the Bank of England in London on 19 October 1877. George Drummond was a partner of Drummonds Bank, with offices at Charing Cross, London, and he chose to buy Swaylands due to its proximity to Tonbridge railway station, from where he could commute by train to the bank's premises.

Between 1879 and 1882 George Drummond made further additions to the house. He initially employed architect George Devey, but dismissed him after litigation. But plans for the house continued with the involvement of local builder, Hope Constable. George Drummond commissioned the arts and crafts architect, Sir Mervyn E. Macartney to build the vast elongated mansion that it is today.

Many of the additions were for entertainment and to demonstrate wealth and hospitality. By this time, whilst the principal drawing and music rooms were in the original villa, there was also a billiards room, ballroom, orangery, conservatory and palm house. There were also extensive bedrooms and servants’ quarters in the main house. Together with all of the farm buildings, dairy and ancillary accommodation on the Swaylands estate. George Drummond gradually bought surrounding farms and, by 1919, the estate had grown to 900 acres.

After George Drummond died in 1917 his son and heir, George Henry Drummond, sold the property in 1919 and the family dispersed. The estate was sold in 12 lots and the grounds shrank to the proportions of William Woodgate's vision.

Sir Ernest Cassel bought Swaylands from George Henry Drummond in 1919 in order to turn it into a hospital for functional nervous disorders, Cassel Hospital. He was struck by the inadequate mental health provision for soldiers returning from the First World War. It was not his first venture in this field: he endowed a hospital at Midhurst, Sussex, for chest disorders, called King Edward VII's Hospital.[3] Ernest Cassel conveyed Swaylands to the trustees of the Cassel Hospital and he was an ex officio President of the General Committee. The stated objectives of the Cassel Hospital were “To treat persons suffering from nervous disorders on the terms of patients contributing some portion of the cost of their maintenance. To carry on… research work in connection with such disorders.”

There were various minor alterations made to the interior of the building at Swaylands in order that it may function as a hospital for 54 patients. The building was ready for occupation in May 1921.

The grounds and exterior of the house were virtually unchanged in Ernest Cassel's time. The cricket pitch was used by staff and patients, a nine-hole golf course was laid out by patients in the parklands and new tennis courts were laid. Such sports were seen as a form of treatment.

The stable block was converted into accommodation for nurses in 1927.

At the advent of the Second World War, the government gave notice that Swaylands was to be requisitioned as a military hospital. Cassel Hospital found a temporary home at Ash Hall Hotel, Stoke-on-Trent. The military hospital was for skin diseases and catered for 200 patients, with a full complement of medical staff. The total population at Swaylands during the Second World War was as many as 400.

The rector of Bidborough mentions bombs falling in the rockery in his historical notes. Some of the shattered sandstone was taken away to repair the church tower in Bidborough.

At the end of the war, Swaylands was available for the Cassel Hospital to return. However, minutes of meetings show that the board of the hospital realised they could not cope with the uneconomic building. Instead, Cassel Hospital went to Ham Common in Surrey, where it remains.

Middlesex County Council bought the estate[4] in poor condition in 1948. Swaylands opened as a “Special Needs Residential School for Boys” in 1949. It initially opened with 4 teachers and 16 pupils. As refurbishments continued, the school rose to 200 pupils. At that time, the school was the largest residential school for boys with special educational needs in the UK. During ownership by Middlesex County Council the conservatory was demolished.

The London Borough of Barnet struggled to afford the maintenance of the estate, especially the main house. The financial problems coincided with a national change in thinking about the efficacy of sending such children to a location distant, and different, from their homes. The school closed in 1994.

Gama International bought Swaylands in 1995 with the intention of developing a health centre, but 5 years later the necessary money and planning permission was not forthcoming and the estate was sold for less than the purchase price. Continued deterioration of the house and grounds occurred during this period.

Thereafter Swaylands was purchased by a series of property developers, and then by Heritable Capital Partners Limited (a subsidiary of Heritable Capital Bank), with a view to redevelopment as apartments. Towards the end of the restoration of the main house and gardens, Heritable Capital Partners Limited entered administration (on 15 October 2008),[5] a victim of the global financial crisis. Ernst & Young were appointed as administrators, and the restoration of the original house, construction of two additional new residential blocks and restoration of the gardens and grounds continued to completion.

The main house now comprises 28 apartments. There are 6 houses in the former stables, and two new residential buildings: Woodgate Manor and Drummond Hall, each comprising around 10 apartments. The two new residential buildings are designed to complement the architecture of the original house.

In 2015 three men were jailed for indecent assaults at Swaylands at the time when it was a school.[6]

Description

Swaylands is situated less than 1 mile to the south-east of the village of Penshurst, Kent, England. The site is bounded to the north-east by Rogues Hill on Penshurst Road, to the south-east by a minor road, and to the north-west and south-west by farmland. The main house stands close to the north-east boundary, with south-westerly views out over the landscape, towards its boundary on the banks of the River Medway, in the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Principal buildings

Swaylands House (listed grade II) is a country house built of red brick with blue diaper work and stone dressings.[7] The long, Tudor-style, building has a main south front of three storeys with a projecting three-bay centre and an octagonal battlemented corner tower. In 2010 two new buildings were completed to complement the architecture of the original house, Drummond Hall and Woodgate Manor. The estate also features a Lodge house at its entrance, and the smaller Clockhouse Mews buildings.

Gardens

The main garden lies to the south-west of the house where an extensive series of grass terraces extends from below the stone wall of the top terrace. To the south-west of the original house is a sunken rose garden, replanted in 1994 and 2010.

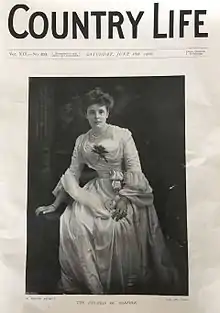

The gardens were described in detail in Country Life in the edition from 16 June 1906.[8] In the Country Life description it is noted that, for twenty years, George Drummond had been, with the assistance of his gardener Hosier, transforming the site into a garden of "rare charm and picturesque beauty.... The terracing is a triumph of landscape gardening.... It is a pure delight to sit here in the sun, surrounded with these flower masses, and look across to the misty Sussex hills in the far distance."

A complex of terracing to the south-east of the house is shown on a sale plan of 1877. Since the gothic finials to the short stone piers bordering the sets of steps match those at nearby Penshurst Place and the walled staircase at the south-east end of the terrace is similar to that at Nonnington Park, Kent, the terrace is thought to be by George Devey.

George Drummond was assisted by his gardener, Christopher Hosier, and Hosier's son, in the building of the 5 acre rockery. Hope Constable's building firm provided stonemasons to arrange the massive sandstone boulders which are from a quarry in nearby Langton Green. Waterfalls and lakes completed the design and were fed by a combination of rainwater and water pumped from the nearby Medway river.

From the centre of the south-west front, steps lead down through the terrace wall, continuing in a walk which leads to and round the western boundary of the pleasure grounds, divided from the park beyond by a ha-ha. A path from the south-east end of the house also leads south-west down steps from the top terrace, this straight walk meeting a cross-walk; immediately to the south-east of the junction is a small late 19th century classical pavilion. This garden building is surrounded by trees and looks onto an expanse of level lawn lying to the south-west (formerly the cricket pitch), the northern edge of which is marked by a path bordered with yews. This area was replanted with trees in about 2010. The flower beds, pond and rockery have been substantially restored.

After restoration, the Estate is maintained by gardeners employed by the Board of Management. In season, the Estate is home to a large number of Sheep which graze the fields to the south of the main buildings.

Owners

William Woodgate was part of an old Kentish family.[9] There were Woodgate's at Stonewall Park, near Chiddingstone.[10] William's father, William Francis Woodgate (1770-1828), owned Somerhill, a large mansion on the outskirts of Tonbridge, which was in the family since 1712.

Edward Cropper was a director of the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company and he owned interests in slate quarries in Pembrokeshire. The 1861 census describes him as a merchant and Justice of the Peace. By 1871 he was described as a Magistrate in the County of Kent.

George Drummond was a partner in Drummonds Bank situated on the corner of Whitehall and Trafalgar Square, London. His ancestor, Andrew Drummond, came from Perthshire in the early 1700s and practised as a goldsmith in Angel Court, London. He opened his first bank in 1717[11] at 49 Charing Cross, London. George married a granddaughter of the Duke of Rutland, Elizabeth Cecile Sophia Norman, with whom he lived at Swaylands.

Lieutenant David Robert Drummond, aged thirty, was the second son of George Drummond, and is named in the village Church among those Penshurst residents who gave their life in the First World War. In 1911 the census records him working as a banker and living in Chelsea. David had been in the army since joining the Black Watch in 1903, and was quickly given a commission one year later in the Scots Guards. As a lieutenant, he arrived in France in October 1914, where he was involved in the First Battle of Ypres. He died in action on 3 November 1914 and was originally buried at the scene of the battle but the site of the grave was later lost. After David's death, the wife of a brother officer wrote to his widow; “One night there was a wounded man in the trench a little way off. They heard him moaning and Mr Drummond managed to get to him and give him some morphia. The poor man died in the night, his last hours painless owing to Mr Drummond’s act. Another day they passed a wounded man lying on the ground in the cold, waiting to be picked up. Mr Drummond took his Burberry, covered the man with it, and left it there. Considering what coats mean to them out there, it was a splendidly kind and noble action.” David's death was described by his captain; “Just a hurried line on the march to tell you about poor David; he was shot through the head by a sniper and thank god suffered no pain. We buried him that night. I got a parson to say a few words over his grave, and I put up a rough cross I cut out of wood with his name and regiment on it. We can ill spare him - one of the best officers I had and the most unselfish fellow I have met. I am simply miserable about him.”

Sir Ernest Cassel from 1919

The freehold of the Estate is today privately owned by its residents.

Guests

George Drummond often entertained his close friend the Prince of Wales – later to become King Edward VII – at Swaylands.[12]

Visitors to Swaylands included the writer and poet Siegfried Sassoon, and the author of the stage play and book, Peter Pan, J. M. Barrie.[13]

References

- ↑ Thorne, Marianne (April 2001). Social History of Swaylands.

- ↑ "George Devey, Victorian architect, 1820-1886". Leigh & District Historical Society. 11 June 2014.

- ↑ Hugh, Chrisholm. Encyclopedia Britannica (12th ed.). Cassel, Sir Ernest Joseph: London & New York.

- ↑ "Swaylands School, Kent". National Archive.

- ↑ "Heritable Capital Partners Limited". Companies House beta.

- ↑ "Swaylands School: Three men jailed over sex abuse". BBC News. 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Swaylands (Grade II) (1001280)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ↑ "Gardens Old and New". Country Life: 7. 16 June 1906.

- ↑ "The Woodgates". Tonbridge History.

- ↑ "A history of the Woodgates of Stonewall Park and of Summerhill in Kent, and their connections". archive.org. 1909.

- ↑ RBS History. Messrs Drummond, London, c1712 - to date.

- ↑ Watson, Andrea (21 December 2007). "Classy Convert". Daily Express.

- ↑ Watson, Andrea (21 December 2007). "Classy Convert". Daily Express.