As with any material implanted in the body, it is important to minimize or eliminate foreign body response and maximize effectual integration. Neural implants have the potential to increase the quality of life for patients with such disabilities as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, epilepsy, depression, and migraines. With the complexity of interfaces between a neural implant and brain tissue, adverse reactions such as fibrous tissue encapsulation that hinder the functionality, occur. Surface modifications to these implants can help improve the tissue-implant interface, increasing the lifetime and effectiveness of the implant.

Background on Intracranial Electrodes

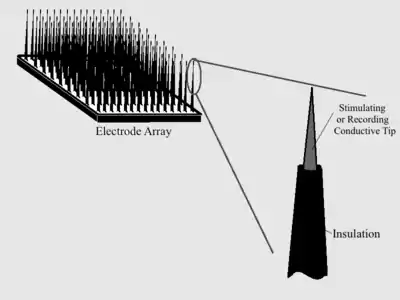

Intracranial electrodes consist of conductive electrode arrays implanted on a polymer or silicon, or a wire electrode with an exposed tip and insulation everywhere that stimulation or recording is not desired. Biocompatibility is essential for the entire implant, but special attention is paid to the actual electrodes since they are the site producing the desired function.

Issues with Current Intracranial Electrodes

One main physiological issue that current long-term implanted electrodes suffer from are fibrous glial encapsulations after implantation. This encapsulation is due to the poor biocompatibility and biostability (integration at the hard electrode and soft tissue interface) of many neural electrodes being used today. The encapsulation causes a reduced signal intensity because of the increased electrical impedance and decreased charge transfer between the electrode and the tissue. The encapsulation causes decreased efficiency, performance, and durability.

Electrical impedance is the opposition to current flow with an applied voltage, usually represented as Z in units of ohms (Ω). The impedance of an electrode is especially important as it is directly related to its effectiveness. A high impedance causes poor charge transfer and thus poor electrode performance for either stimulating or recording the neural tissue. Electrode impedance is related to surface area at the interface between the electrode and the tissue. At electrode sites, the total impedance is controlled by the double-layer capacitance.[1] The capacitance value is directly related to the surface area. Increasing the surface area at the electrode-tissue interface will increase the capacitance and thus decrease the impedance. The equation below describes the inverse relationship between the capacitance and impedance.

where i is the imaginary unit, w is the frequency of the current, C is capacitance, and R is resistance.

A desirable electrode would have a low impedance meaning a higher surface area. One method to increase this area is coating the electrode surfaces with a variety of materials. Many new materials and techniques are being researched to improve the behavior of neural electrodes. Currently, research is being done to increase the biocompatibility and integration of electrodes in neural tissue; this research is discussed in more detail below.

Importance of Surface Chemistry

Surface chemistry of implantable electrodes proves to be more of a design concern for chronically implanted electrodes as compared to those with only acute implantation times. For acute implantations, the main concerns are laceration damage and degradation of particles left behind after electrode removal. For chronically implanted electrodes the cellular response and tissue encapsulation of the foreign body, regardless of degradation – even for materials that are highly biocompatible – are the primary concerns. Degradation, however, is still undesirable because particles can be toxic to tissue, can spread throughout the body, and even trigger an allergic response. Surface chemistry is an area of science applicable to biological implants. Bulk material properties are important when considering applications, however, it is the materials' surface (top several layers of molecules) that determines the biological response and is therefore the key to implant success.[2] Implants within the central nervous system are unique in their manor of cellular response; there is little room for error. Prosthesis in these areas are typically electrodes or electrode arrays.

Electrochemical Considerations

Electrodes, especially stimulating electrodes and the high current density they discharge, can raise electrochemical issues. Electrodes will be surrounded by tissue and electrolytes; stimulation, resultant electric fields, and induced polarizations will change local ion concentrations and local pH which can then cause problems such as material corrosion and electrode fouling.[3]

Pourbiax diagrams will show the phases that a material will take in an aqueous environment, based on electrical potential and pH. The brain maintains a pH of around 7.2 to 7.4, and from the Pourbaix diagram of platinum[3] it can be seen that at around 0.8 volts Pt at the surface will oxidize to PtO2, and at around 1.6 volts, PtO2 will oxidize to PtO3. These voltages do not seem to be outside of reasonable range for neural stimulation. The voltage required for stimulation may change significantly over the life of a single electrode. This change is required to maintain a consistent current output through variations in the surrounding environmental resistance. The changes in resistance may be due to: adsorption of material onto the electrode, corrosion of the electrode, encapsulation of the electrode in fibrous tissue – known as a glial scar, or changes in the chemical environment around the electrode. Ohm's law V = I * R shows the interdependence of voltage, current and resistance. When voltage change causes a crossing of equilibrium lines as seen in a Pourbaix diagram during a stimulation, the changing polarization of the electrode is no longer linear.[3] Undesirable polarization can lead to adverse effects such as corrosion, fouling, and toxicity. Because of this equilibrium potential, pH, and required current density should be considered when making material choice since these can affect the surface chemistry and biocompatibility of the implant.[3]

Corrosion

Corrosion is a major issue with neural electrodes. Corrosion can occur because electrode metals are placed in an electrolytic solution, where the presence of current can either increase the rate of corrosion mechanisms or overcome limiting activation energies. Redox reactions are a mechanism of corrosion that can lead to dissolution of ions from the electrode surface. There is a base level of metal ions in tissue, however, when these levels increase beyond threshold values the ions become toxic and can cause severe health problems.[4] In addition, the fidelity of the electrode system can be compromised. Knowing the impedance of an electrode is important whether the electrode is used for stimulation or recording. When degradation of the electrode surface occurs because of corrosion, the surface area increases with its roughness. Calculating a new electrode impedance to compensate for the change in surface area once implanted it is not easy. This computational flaw can skew data from recording or pose a dangerous obstacle limiting safe stimulation.

Electrode Fouling

Electrode fouling is a major hindrance on the performance of electrodes. Few materials are completely bioinert, as in they trigger no bodily reaction. Some material that may be bioinert in theory fails to be ideal in practice because of defects in their formation, processing, manufacturing or sterilization. Fouling can be caused by adsorption of proteins, fibrous tissue, trapped cells or dead cell fragments, bacteria, or any other reactive particle. Protein adsorption is influenced by the nature and geometry of domains including hydrophobicity, polar and ionic interactions of the material and surrounding particles, charge distribution, kinetic movement, and pH.[3] Phagocytosis of bacteria and other particles is mainly affected by surface charge, hydrophobicity, and chemical composition of the implant. It is important to note that the initial environment the implant is subjected to after implantation is different and unique compared to the environment after some time has passed since the area will undergo wound repair; the body's natural healing of the trauma will cause changes in local pH, electrolyte concentrations, and the presence and activity of biological compounds.

Properties of Metals

For many reasons known and unknown, protein adsorption varies from material to material. Two of the biggest determining factors that have been observed are surface roughness and surface free energy.[5] In the case of exposed electrodes, it is desirable to have the adsorbed protein layer as thin as possible to increase sensitivity and performance. Noble metals are an obvious choice for achieving biocompatibility; however, when acting as electrodes, some of these noble metals will actually participate in the reaction, deteriorate, and trigger adverse effects via lost particles. The most (noble metals) are gold (Au), platinum (Pt), and iridium (Ir).

| Material | Nobility (in volts, to the simplified product) | Surface free energy , (eV/Å2), in (111) plane[6] | RMS roughness @ before exposure; 7; 28 days post exposure (nm)[5] | Thickness of protein film (nm) @ 1; 7; 28 days post-exposure[5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | 1.42 V to Au3+ | 0.078 | 1.4; 22; 68 | 13; 110; 340 |

| Platinum (Pt) | 1.18 V to Pt2+ | 0.137 | 0.8; 51; x | 11; 113; x |

| Iridium (Ir) | 1.156 V to Ir3+ | 0.204 | 2.4; 29; 185 | 7; 108; 420 |

- An x refers to bad data - Nobility is the measure of potential needed to chemically reduce the material; these were measured against a standard hydrogen electrode. - RMS roughness is a measure of deviation from the mean plane. - Protein was measured in vitro with ellipsometry and step-technique atomic force microscopy, with metal in a dilute plasma solution. | ||||

- = Surface free energy

- Es = Total energy per unit cell at surface

- Eb = Total energy per unit cell in bulk of material

- A = Area of surface

The properties of titanium were also investigated in the study that produced the data[3] for the above table, however, its properties are not listed here since its poor conductive properties make it unsuitable for neural implants. Insight on titanium's surface chemistry may give direction to future research. Titanium has the roughest and most hydrophilic surface of any metal described thus far (the importance of protein adsorption, its mechanisms, and the interplay of hydrophilic properties are discusses further in the hydrogels section of the page). Titanium adsorbed the thickest protein layer after the first day and still after the seventh day, but actually had its thickness reduced by the 28th day. Gold, platinum and iridium's protein layers all continued to grow up until the 28th day, but the rates slowed over time.[5]

Two more conductive materials that have notable characteristics are tungsten and indium tin oxide. Tungsten is electrically conductive and can be manufactured down to a very fine point, and for this reason has been used in intraspinal microstimulation (ISMS) for mapping out spinal cords during terminal surgeries. Tungsten electrodes, however, can corrode and form tungstic ions in the presence of H2O2 and/or O2. Tungstic acid has been seen to be highly toxic to cat motorneurons,[7] and for this reason, does not currently make a suitable material for chronic implants. Indium tin oxide (ITO) has been used as electrode material for in vitro studies. ITO electrodes are very precise when stimulating and recording and when placed amongst plasma proteins, develop and maintain the thinnest protein layer compared to the other materials so far mentioned.[5] It may have potential for acute in vivo usage, but over time, it has been observed to let go of particles producing highly toxic effects.[8]

Mechanical Adaptations

A variety of mechanical adaptations, such as tip geometry and surface roughness, to aid in neural implant design have been investigated and implemented in recent years. The geometry of an electrode affects the shape of the electric field emitted. The electric field shape, in turn, affects the current density produced by the electrode. Determining optimum surface roughness for neural implants proves to be a challenging topic. Smooth surfaces may be preferable to rougher ones as they may decrease the likelihood of bacterial adsorption and infection. Smooth surfaces would also make it more difficult for the initiation of a corrosion cell. However, creating a rougher, porous surface, may prove beneficial for at least two reasons: decreased potential polarization at the electrode surface as a result of increased surface area and decreased current density, and a decrease in fibrous tissue encapsulation thickness due to opportunity for tissue ingrowth. It has been determined that if interconnected pores with sizes between 25 and 150 micrometers, ingrowth of tissue can occur and can decrease the exterior tissue encapsulation thickness by a factor of approximately 10 (compared to a smooth electrode such as polished platinum-iridium).[3]

Coatings

Different material coatings for neural electrode surfaces are being researched to improve the long-term integration of electrodes in the neural tissue by improving biocompatibility, mechanical properties, and the charge transport between the electrode and the living tissue. The electrode functionality can be increased by adding a surface modification on the electrode of a conducting porous polymer with the incorporation of cell adhesion peptides, proteins, and anti-inflammatory drugs.[9]

Conducting polymers

Polymers, especially conductive ones, have been widely researched to coat electrode surfaces. Conductive polymers are organic materials that have properties similar to metals and semiconductors in their ability conduct electricity and attractive optical properties.[9] These materials have rough surfaces, resulting in large surface area and charge density. Conducting polymer coatings have been shown to improve the performance and stability of neural electrode.

Conductive polymers have been shown to lower the impedance of electrodes (an important property as mentioned above), increase the charge density, and improve the mechanical interface between the soft tissue and hard electrode. The porous (rough) structure of many conductive polymer coatings on the electrode increases the surface area.[9] The high surface area of conductive polymers is directly related to decreased impedance and charge transfer improvement at the tissue-electrode interface. This improved charge transfer allows for better recording and stimulating in neural application. Table 2 below shows some common impedance and charge density values of different electrodes at a frequency of 1 kHz, which is the characteristic of neural biological activity. The porous, high surface area of the conductive polymer coatings allows for target cell adhesion (increased cell and tissue integration), which increase the bio-compatibility and stability of the device.

| Electrode type | Impedance at 1 kHz (kΩ) | Charge density (mC·cm−2)[10] |

|---|---|---|

| Bare gold electrode | 400 [11] | 3.1 [10] |

| Gold electrode with PPy/PSS coating | <10 [12] | 63.0 [10] |

| Gold electrode with PEDOT coating | 3–6 [13] | 54.6 [10] |

Conducting polymer coatings as mentioned above can greatly improve the interface between the soft tissue in the body and the hard electrode surface. Polymers are softer, which reduces the inflammation from strain mismatch between tissue and electrode surface. The reduced inflammatory reaction causes a decrease in thickness of the glial encapsulation which causes signal degeneration. The elastic modulus of silicon (a common material that electrodes are made from) is around 100 GPa and the tissue in the brain is about 100 kPa.[14] The electrode modulus (stiffness) is about 100 times greater than that of the tissue in the brain. For the best device integration in the body, it is important to get the stiffness between the two to be as similar as possible. To improve this interface, a conductive polymer coating (smaller modulus than the electrode) can be applied to the electrode surface which causes a gradient of mechanical properties to act as a mediator between the hard and soft surfaces. The added polymer coating reduces the stiffness of the electrode and allows for better integration of the electrode. The figure to the right shows a graph of how the modulus changes when integrating the polymer coating onto the electrode.

Processing of conducting polymer coatings

Another benefit of using conductive polymers as a coating for neural devices is the ease of synthesis and flexibility in processing.[9] Conducting polymers can be directly "deposited onto electrode surfaces with precisely controlled morphologies".[14] There are two current ways conducting polymers can be deposited onto electrode surfaces which are chemical polymerization and electrochemical polymerization. In the application for neural implants, electrochemical polymerization is used because of its ability to create thin films and the ease of synthesis. Films can be formed on the order of 20 nm.[14] Electrochemical polymerization (electrochemical deposition) is performed using a three-electrode configuration in a solution of the monomer of the desired polymer, a solvent, and an electrolyte (dopant). In the case of depositing a polymer coating onto electrode a common dopant used is poly (styrene sulfonate) or PSS because of its stability and biocompatibility.[14] Two common conductive polymers being investigated for coatings use PSS as a dopant to be electrochemically deposited onto the electrode surface (see sections below).

Specific conducting polymers being researched

Polypyrrole

One conducting polymer coating that has shown promising results for improving the performance of neural electrodes is polypyrrole (PPy). Polypyrrole has great biocompatibility and conductive properties, which makes it a good option for the use in neural electrodes. PPy has been shown to have a good interaction with biological tissues. This is due to the boundary it creates between the hard electrode and the soft tissue. PPy has been shown to support cell adhesion and growth of a number of different cell types including primary neurons which is important in neural implants.[12] PPy also decreases the impedance of the electrode system by increasing the roughness on the surface. The roughness on the electrode surface is directly related to an increased surface area (increased neuron interface with electrode) which increases the signal conduction. In one paper, polypyrrole (PPy) was doped with polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) to electrochemically deposit a polypyrrole coating on the electrode surface. The film was coated onto the electrode at different thickness, increasing the roughness. The increased roughness (increased effective surface) leads to a decreased overall electrode impedance from about 400 kΩ (bare stent) to less than 10 kΩ (PPy/PSS coating) at 1 kHz.[12] This decrease in impedance leads to improved charge transfer from the electrode to the tissue and an overall more effective electrode for recording and stimulating applications.

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT)

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) is another conducting polymer that is being investigated for coating an electrode surface. Some benefits of PEDOT over PPy is that it is more stable to oxidation and more conductive; however PPy is much cheaper. As with PPy, PEDOT has been shown to decrease the electrical impedance. In one article, a PEDOT coating was electrochemically deposited on to gold recording electrodes.[15] The results showed that impedance of the electrode decreased significantly when the PEDOT coating was added. The unmodified gold electrodes had an impedance of 500–1000 kΩ, while the modified gold electrode with the PEDOT coating had an impedance of 3–6 kΩ.[13] The paper also showed that the interaction between the polymer and neurons improved the stability and durability of the electrode. The study concluded that by adding a conductive polymer the impedance of the electrode system decreased, which increased the charge transfer making a more effective electrode. The ease and control of electrochemically depositing conducting coatings onto electrode surfaces makes it a very attractive surface modification for neural electrodes.

Growth factors and pharmaceutical agents

Neural progenitor cells (NPCs)

Seeding implants with growth factors, such as neural progenitor cells (NPCs), improves the brain-implant interface. NPCs are progenitor cells that have the ability to differentiate into neurons or cells found in the brain. By coating the implant with NPCs, it can reduce the foreign body reaction and improve biocompatibility. To attach the NPCs, prior surface modification of the implant is required; these modifications can be done via the immobilization of laminin (an extracellular matrix derived protein) on an implant, such as silicon. To verify the success of surface immobilization, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and an analysis of hydrophobicity can be used. The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy can be used to characterize the chemical composition of the surface or a contact angle goniometer can be used to determine the contact angle of water to determine the hydrophobicity. A higher contact angle indicates higher hydrophobicity, showing successful modification of the surface via the laminin protein. The laminin immobilized surface promotes the attachment and growth of the NPCs and also allows for their differentiation, thereby reducing the glial response and foreign body response to the implant.[16]

Nerve growth factors (NGFs)

Using nerve growth factor (NGF) as a neurotrophic co-dopant could induce ideal cell responses in vivo. NGF is a water-soluble protein that promotes the survival and differentiation of neurons. The addition of NGF into polymeric films can induce biological interactions without compromising the conductive properties or the morphology of the polymeric film. Various polymers such as PPy, PEDOT, as well as collagen, can be used as electrode coatings. Extended neurites for both the PPy and PEDOT show that the NGF is biologically active.[16]

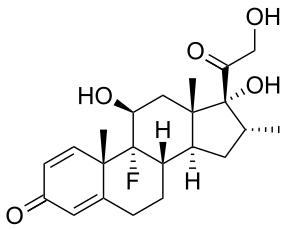

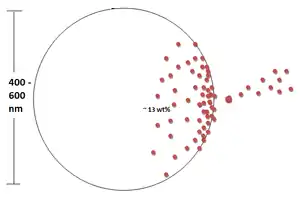

Anti-inflammatory drugs

Dexamethasone (DEX) is a glucocorticoid that is used as an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agent. PLGA nanoparticles loaded with DEX via oil-in-water emulsion/solvent evaporation method can be embedded in alginate hydrogel matrices. To quantify the amount of DEX that was successfully seeding into the nanoparticle, UV spectrophotometry can be used. It has been shown that the amount of DEX that can be successfully loaded into the nanoparticles was ≈13 wt% and the typical particle size ranged from 400 to 600 nm.

In vitro tests have revealed that the impedance of the nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel-coated electrodes have similar impedance to the non-coated electrode (bare gold). This shows that the nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel coating does not significantly hinder the electrical transport. The in vivo tests have shown that the impedance amplitude of the DEX-loaded electrodes was maintained at the same level it was at initially. However, non-coated electrodes had an impedance about 3 times greater than its original impedance 2 weeks earlier. This addition of anti-inflammatory drugs via nanoparticles indicates that this form of surface modification does not have a negative effect on the electrodes performance.[14]

Hydrogels

Hydrogel modifications, as with other coatings, are designed to improve the body's response to the implant and thereby improve their consistency and long-term performance. Hydrogel surface modifications achieve this by significantly altering the hydrophilicity of the neural implant surface to one that is less favorable for protein adsorption.[17] In general, protein adsorption increases with increasing hydrophobicity as a result of the decreased Gibbs energy from the energetically favorable reaction (as seen in the equation below)[2]

Water molecules are bonded to both the proteins and to the surface of the implant; as the protein binds to the implant, water molecules are liberated, resulting in an entropy gain, decreasing the overall energy in the system.[18] For hydrophilic surfaces, this reaction is energetically unfavorable due to the strong attachment of water to the surface, hence the decreased protein adsorption. The decrease in protein adsorption is beneficial for the implant as it limits the body's ability to both recognize the implant as a foreign material as well as attach potentially deleterious cells such as astrocytes and fibroblasts that can create fibrous glial scars around the implant and hinder stimulating and recording processes. Increasing the hydrophilicity can also enhance the electrical signal transfer by creating a stable ionic conductance layer. However, increasing the water content of the hydrogel too much can cause swelling and eventually mechanical instability.[17] An appropriate water balance must be created to optimize the efficacy of the implant coating.

Proteins

Significant nonspecific protein adsorption during implantation can cause adverse effects. However, some proteins can be beneficial in stabilizing the implant by reducing micro-motion and implant migration, as well as improving the signal quality through increased neuron connection; improving the long-term performance. Instead of relying on the native cells to secrete these proteins, they can be added to the surface of the material prior to implantation. The surface modification of biomaterials with proteins has been done with great success in various regions of the body. However, since the anatomy of the brain is different from the rest of the body, the types of proteins that must be used in these applications vary from those used elsewhere. Proteins like laminin that promotes neuronal outgrowth and L1 that promotes axonal outgrowth have shown great promise in surface modification applications; L1 more so than laminin because of the decreased attachment associated with astrocytes – the cells responsible for glial scar formation.[19] Proteins are typically added to the material surface via self-assembled monolayer (SAM) formation.

References

- ↑ Jayapriya, J; et al. (2012). "Preparation and characterization of biocompatible carbon electrodes". Composites Part B: Engineering. 43 (3): 1329–1335. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.10.019.

- 1 2 Mikos, A.G.; Temenoff, J.S. (2008). "Biomaterials: The Intersection of Biology and Materials Science": 138–152.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Beard, R.B.; et al. (1992). "Biocompatibility Considerations at Stimulating Electrode Interfaces". Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 20 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/bf02368539. PMID 1443832. S2CID 31061691.

- ↑ Sargeant, Goswami (2007). "Hip implants – Paper VI – Ion concentrations". Materials & Design. 28: 155–171. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2005.05.018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Selvakumaran, Jamunanithy; et al. (2008). "Protein adsorption on materials for recording sites on implantable microelectrodes" (PDF). J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 19 (1): 143–151. doi:10.1007/s10856-007-3110-x. PMID 17587151. S2CID 829137.

- ↑ Needs, R; Mansfield, M (1989). "Calculations of the surface stress tensor and surface energy of the (111) surfaces of iridium, platinum and gold". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 1 (41): 7555–7563. Bibcode:1989JPCM....1.7555N. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/1/41/006. S2CID 250915999.

- ↑ Schwindt, P.C.; Spain, W.; Crill, W (1984). "Epileptogenic action of tungstic acid gel on cat lumbar motoneurons". Brain Res. 291 (1): 140–144. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(84)90660-7. PMID 6697179. S2CID 20368602.

- ↑ Lison, D; et al. (2009). "Sintered indium-tin-oxide (ITO) particles: a new pneumotoxic entity". Industrial Toxicology and Occupational Medicine, Catholic University of Louvain, Brussels. 108 (2): 472–481. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp014. PMID 19176593.

- 1 2 3 4 Guimard, Nathalie; et al. (2007). "Conducting polymers in biomedical engineering". Progress in Polymer Science. 32 (8–9): 876–921. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.012.

- 1 2 3 4 Harris, Alexander R; Morgan, Simeon J; Chen, Jun; Kapsa, Robert M I; Wallace, Gordon G; Paolini, Antonio G (2013). "Conducting polymer coated neural recording electrodes". Journal of Neural Engineering. 10 (1): 016004. Bibcode:2013JNEng..10a6004H. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/10/1/016004. ISSN 1741-2560. PMID 23234724. S2CID 39479693.

- ↑ Green, Rylie A.; Lovell, Nigel H.; Wallace, Gordon G.; Poole-Warren, Laura A. (2008). "Conducting polymers for neural interfaces: Challenges in developing an effective long-term implant". Biomaterials. 29 (24–25): 3393–3399. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.047. ISSN 0142-9612. PMID 18501423.

- 1 2 3 Cui, Xinyan; et al. (2001). "Electrochemical deposition and characterization of conducting polymer polypyrrole/PSS on multichannel neural probes". Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 93: 8–18. doi:10.1016/S0924-4247(01)00637-9.

- 1 2 Ludwig, Kip; et al. (2011). "PEDOT polymer coatings facilitate smaller neural recording electrodes". Journal of Neural Engineering. 8 (1): 014001. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/8/1/014001. hdl:2027.42/90823. PMC 3415981. PMID 21245527.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dong-Hwan, Kim; et al. (2008). "Chapter 7: Soft, Fuzzy, and Bioactive Conducting Polymers for Improving the Chronic Performance of Neural Prosthetic Devices". Indwelling Neural Implants: Strategies for Contending with the in Vivo Environment.

- ↑ Cui, Xinyan; et al. (2003). "Electrochemical deposition and characterization of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) on neural microelectrode arrays". Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 89 (1–2): 92–102. doi:10.1016/s0925-4005(02)00448-3.

- 1 2 Azemi, E; et al. (2010). "Seeding neural progenitor cells on silicon-based neural probes". Journal of Neurosurgery. 113 (3): 673–681. doi:10.3171/2010.1.jns09313. PMID 20151783.

- 1 2 Li, Rao; et al. (2012). "Polyethylene glycol-containing polyurethane hydrogel coatings for improving the biocompatibility of neural electrodes". Acta Biomaterialia. 8 (6): 2233–2242. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.001. PMID 22406507.

- ↑ Dietschweiler, Coni; Sander, Michael (2007). "Protein adsorption at solid surfaces": 8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Azemi, Erdrin; Stauffer, William R.; Gostock, Mark S.; Lagenaur, Carl F.; Cui, Xinyan Tracy (2008). "Surface immobilization of neural adhesion molecule L1 for improving the biocompatibility of chronic neural probes: In vitro characterization". Acta Biomaterialia. 4 (5): 1208–1217. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2008.02.028. ISSN 1742-7061. PMID 18420473.