Starbase sign with production site in the background | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Boca Chica, Cameron County, Texas, United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 25°59′15″N 97°11′11″W / 25.98750°N 97.18639°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | SpaceX | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch pad(s) | 2 (1 suborbital, 1 orbital) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Starbase is a spaceport, production, and development facility for Starship rockets, located at Boca Chica, Texas, United States. It has been under construction since the late 2010s by SpaceX, an American aerospace manufacturer.

When conceptualized, its stated purpose was "to provide SpaceX an exclusive launch site that would allow the company to accommodate its launch manifest and meet tight launch windows."[4] The launch site was originally intended to support launches of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicles as well as "a variety of reusable suborbital launch vehicles",[4] but in early 2018, SpaceX announced a change of plans, stating that the launch site would be used exclusively for SpaceX's next-generation launch vehicle, Starship.[5] Between 2018 and 2020, the site added significant rocket production and test capacity. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk indicated in 2014 that he expected "commercial astronauts, private astronauts, to be departing from South Texas,"[6] and eventually launching spacecraft to Mars from the site.[7]

Between 2012 and 2014, SpaceX considered seven potential locations around the United States for the new commercial launch facility. Generally, for orbital launches an ideal site would have an easterly water overflight path for safety and be located as close to the equator as possible in order to take advantage of the Earth's rotational speed. For much of this period, a parcel of land adjacent to Boca Chica Beach near Brownsville, Texas, was the leading candidate location, during an extended period while the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) conducted an extensive environmental assessment on the use of the Texas location as a launch site. Also during this period, SpaceX began acquiring land in the area, purchasing approximately 41 acres (170,000 m2) and leasing 57 acres (230,000 m2) by July 2014. SpaceX announced in August 2014, that they had selected the location near Brownsville as the location for the new non-governmental launch site,[8] after the final environmental assessment completed and environmental agreements were in place by July 2014.[9][10][11] Integrated Flight Test-1 of Starship made it SpaceX's fourth active launch facility, following three launch locations that are leased from the US government.

SpaceX conducted a groundbreaking ceremony on the new launch facility in September 2014,[12][6] and soil preparation began in October 2015.[13][14] The first tracking antenna was installed in August 2016, and the first propellant tank arrived in July 2018. In late 2018, construction ramped up considerably, and the site saw the fabrication of the first 9 m-diameter (30 ft) prototype test vehicle, Starhopper, which was tested and flown March–August 2019. Through 2021, additional prototype flight vehicles are being built at the facility for higher-altitude tests. By late 2023, over 2,100 full-time employees were working at the site.[15]

History

Private discussions between SpaceX and state officials about a private launch site began at least as early as 2011.[16] SpaceX CEO Elon Musk mentioned interest in a private launch site for their commercial launches in a September 2011 speech.[17] The company announced in August 2014 that they had chosen Texas as the location for their SpaceX South Texas launch site.[8] Site soil work began in 2015 and major construction of facilities began in late-2018, with rocket engine testing and flight testing beginning in 2019.

The name Starbase began to be used more widely by SpaceX after March 2021 when SpaceX had some discussions described as a "casual enquiry" about incorporating a city to be called Starbase,[18][19] and by early 2022, the Starbase moniker for the SpaceX facilities in south Texas had become common.[20] The site has also been called the "Gateway to Mars", including in a sign outside the launch site.[21][22][23][24]

Starbase is also used sometimes to describe the region of the Boca Chica subdelta peninsula surrounding the SpaceX facilities; see Boca Chica (Texas) § "Starbase", Texas.

Launch site selection and environmental assessment

As early as April 2007, at least five potential locations were publicly known, including "sites in Alaska, California, Florida,[25] Texas and Virginia."[26] In September 2012, it became clear that Georgia and Puerto Rico were also interested in pursuing the new SpaceX commercial spaceport facility.[27] The Camden County, Georgia, Joint Development Authority voted unanimously in November 2012 to "explore developing an aero-spaceport facility" at an Atlantic coastal site to support both horizontal and vertical launch operations.[28] The main Puerto Rico site under consideration was the former Roosevelt Roads Naval Station.[4]: 87 By September 2012, SpaceX was considering seven potential locations around the United States for the new commercial launch pad. Since then, the leading candidate location for the new facility was a parcel of land adjacent to Boca Chica Beach near Brownsville, Texas.[29]

By early 2013, Texas remained the leading candidate for the location of the new SpaceX commercial launch facility, although Florida, Georgia and other locations remained in the running. Legislation was introduced in Texas to enable temporary closure of State beaches during launches, limit liability for noise and other commercial spaceflight risks, as well as considering a package of incentives to encourage SpaceX to locate at Brownsville, Texas.[30][31] 2013 economic estimates showed SpaceX investing approximately US$100 million in the development and construction of the facility[31] A US$15 million incentive package was approved by the Texas Legislature in 2013.[32]

In April 2012, the FAA's Office of Commercial Space Transportation initiated a Notice of Intent to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement[33] and public hearings on the new launch site, which would be located in Cameron County, Texas. The summary then indicated that the Texas site would support up to 12 commercial launches per year, including two Falcon Heavy launches.[34][35][26] The first public meeting was held in May 2012,[35][36] and the FAA released a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the location in south Texas in April 2013. Public hearings on the draft EIS occurred in Brownsville, followed by a public comment period ending in June 2013.[37][38][39] The draft EIS identified three parcels of land—total of 12.4 acres (5.0 ha)—that would notionally be used for the control center. In addition, SpaceX had leased 56.6 acres (22.9 ha) of land adjacent to the terminus of Texas State Highway 4, 20 acres (8.1 ha) of which would be used to develop the vertical launch area; the remainder would remain open space surrounding the launch facility.[4] In July 2014, the FAA officially issued its Record of Decision concerning the Boca Chica Beach facility, and found that "the proposal by Elon Musk's Space Exploration Technologies would have no significant impact on the environment,"[40] approving the proposal and outlining SpaceX's proposal.[40] The company formally announced selection of the Texas location in August 2014.[8]

In September 2013, the State of Texas General Land Office (GLO) and Cameron County signed an agreement outlining how beach closures would be handled in order to support a future SpaceX launch schedule. The agreement is intended to enable both economic development in Cameron County and protect the public's right to have access to Texas state beaches. Under the 2013 Texas plan, beach closures would be allowed but were not expected to exceed a maximum of 15 hours per closure date, with no more than three scheduled space flights between the Saturday prior to Memorial Day and Labor Day, unless the Texas GLO approves.[39]

In 2019, the FAA completed a reevaluation of the SpaceX facilities in South Texas, and in particular the revised plans away from a commercial spaceport to more of a spaceship yard for building and testing rockets at the facility, as well as flying different rockets—SpaceX Starship and prototype test vehicles—from the site than the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy envisioned in the original 2014 environmental assessment.[41] In May and August 2019, the FAA issued a written report with a decision that a new supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) would not be required.[42][43] In May 2021, the FAA issued a written FAQ regarding the FAA's Environmental Review of SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Operations at the Boca Chica Launch Site.[44]

Throughout 2022, Starship's first integrated flight test was delayed extensively, due to delays in the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issuing a license, to allow findings on environmental impact. On 13 June 2022, the FAA announced that Starbase was not creating a significant impact on the environment, yet listed more than 75 actions to be taken before review for an orbital launch license. Some of these actions included a $5,000 contribution to wildlife nonprofits in the area, making sure roadways stay open on certain days of the year, and actions to protect local sea turtle populations.[45]

Land acquisition

Prior to a final decision on the location of the spaceport, SpaceX began purchasing a number of real estate properties in Cameron County, Texas, beginning in June 2012.[37] By July 2014, SpaceX had purchased approximately 41 acres (170,000 m2) and leased 57 acres (230,000 m2) near Boca Chica Village and Boca Chica Beach[46] through a company named Dogleg Park LLC, a reference to the "dogleg" type of trajectory that rockets launched from Boca Chica will be required to follow.[47]

Prior to May 2013, five lots in the Spanish Dagger Subdivision in Boca Chica Village, adjacent to Highway 4 which leads to the proposed launch site, had been purchased. In May 2013, SpaceX purchased an additional three parcels, adding another 1 acre (4,000 m2),[37] plus four more lots with a total of 1.9 acres (7,700 m2) in July 2013, making a total of 12 SpaceX-purchased lots.[32] In November 2013, SpaceX substantially "increased its land holdings in the Boca Chica Beach area from 12 lots to 72 undeveloped lots" purchased, which encompass a total of approximately 24 acres (97,000 m2), in addition to the 56.5 acres (229,000 m2) leased from private property owners.[38] An additional few acres were purchased late in 2013, raising the SpaceX total "from 72 undeveloped lots to 80 lots totaling about 26 acres."[48] In late 2013, SpaceX completed a replat of 13 lots totaling 8.3 acres (34,000 m2) into a subdivision that they have named "Mars Crossing."[49][50]

In February 2014, they purchased 28 additional lots that surround the proposed complex at Boca Chica Beach, raising the SpaceX-owned land to approximately 36 acres (150,000 m2) in addition to the 56-acre (230,000 m2) lease.[49] SpaceX's investments in Cameron County continued in March 2014, with the purchase of more tracts of land, bringing the total number of lots it owned to 90. Public records showed that the total land area that SpaceX then owned through Dogleg Park LLC was roughly 37 acres (150,000 m2). This is in addition to 56.5 acres (229,000 m2) that SpaceX then had under lease.[51] By September 2014, Dogleg Park completed a replat of lots totaling 49.3 acres (200,000 m2) into a second subdivision, this one named "Launch Site Texas", made up of several parcels of property previously purchased. This is the site of the launch site itself while the launch control facility is planned two miles west in the Mars Crossing subdivision. Dogleg Park has also continued purchasing land in Boca Chica, and as of 2014 owned a total of "87 lots equaling more than 100 acres".[50]

SpaceX has also bought and is modifying several residential properties in Boca Chica Village, but apparently planning to leave them in residential use, about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the launch site.[52]

In September 2019, SpaceX extended an offer to buy each of the houses in Boca Chica Village for three times the fair market value along with an offer of VIP invitations to future launch events. The 3x offer was said to be "non-negotiable." Homeowners were given two weeks for this particular offer to remain valid.[53]

In January 2023, Musk shared that SpaceX had acquired nearby Massey's gun range, now known as Massey's rocket test facility.[54]

Construction

Major site construction at SpaceX's launch site in Boca Chica got underway in 2016, with site soil preparation for the launch pad in a process said to take two years, with significant additional soil work and significant construction beginning in late 2018. By September 2019, the site had been "transformed into an operational launch site – outfitted with the ground support equipment needed to support test flights of the methane-fueled Starship vehicles."[55] Lighter construction of fencing and temporary buildings in the control center area had begun in 2014.[50][56]

The Texas launch location was projected in the 2013 draft EIS to include a 20 acres (81,000 m2) vertical launch area and a 12.2 acres (49,000 m2) area for a launch control center and a launch pad directly adjacent to the eastern terminus of Texas State Highway 4.[4] Changes occurred based on actual land SpaceX was able to purchase and replat for the control center and primary spaceship build yard.

SpaceX broke ground on the new launch site in September 2014,[12] but indicated then that the principal work to build the facility was not expected to ramp up until late 2015[6] after the SpaceX launch site development team completed work on Kennedy Space Center Launch Pad 39A, as the same team was expected to manage the work to build the Boca Chica facility. Advance preparation work was expected to commence ahead of that. As of 2014, SpaceX anticipated spending approximately US$100 million over three to four years to build the Texas facility, while the Texas state government expected to spend US$15 million to extend utilities and infrastructure to support the new spaceport.[6] The design phase for the facility was completed by March 2015.[57] In the event, construction was delayed by the destruction of one of SpaceX two Florida launch facilities in a September 2016 rocket explosion, which tied up the launch site design/build team for over a year.

In order to stabilize the waterlogged ground at the coastal site, SpaceX engineers determined that a process known as soil surcharging would be required. For this to happen, some 310,000 cubic yards (240,000 m3) of new soil was trucked to the facility between October 2015 and January 2016.[13][58] In January 2016, following additional soil testing that revealed foundation problems, SpaceX indicated they were not planning to complete construction until 2017, and the first launch from Boca Chica was not expected until late 2018.[14][58][59] In February 2016, SpaceX President and COO Gwynne Shotwell stated that construction had been delayed by poor soil stability at the site, and that "two years of dirt work" would be required before SpaceX could build the launch facility, with construction costs expected to be higher than previously estimated.[60] The first phase of the soil stabilization process was completed by May 2016.[61]

Two 9 m (30 ft) S-band tracking station antennas were installed at the site in 2016–2017.[62] They were formerly used to track the Space Shuttle during launch and landing[63][64] and made operational as tracking resources for crewed Dragon missions in 2018.

A SpaceX-owned 6.5-acre (26,000 m2) photovoltaic power station was installed on site to provide off-grid electrical power near the control center,[11][65][66] The solar farm was installed by SolarCity in January 2018.

Progress on building the pad had slowed considerably through 2017, much slower than either SpaceX or Texas state officials had expected when it was announced in 2014. Support for SpaceX, however, remained fairly strong amongst Texas public officials.[62] In January 2018, COO Shotwell said the pad might be used for "early vehicle testing" by late 2018 or early 2019 but that additional work would be required after that to make it into a full launch site.[67] SpaceX achieved this new target, with prototype rocket and rocket engine ground testing at Boca Chica starting in March 2019, and suborbital flight tests starting in July 2019.

In late 2018, construction ramped up considerably, and the site saw the development of a large propellant tank farm including a 95,000 gallon horizontal liquid oxygen tank[68] and 80,000 gallon liquid methane tank,[69] a gas flare, more offices, and a small flat square launch pad. The Starhopper prototype was relocated to the pad in March 2019, and first flew in late July 2019.[70]

In late 2018, the "Mars Crossing" subdivision developed into a shipyard, with the development of several large hangars, and several concrete jigs, on top of which large steel rocket airframes were fabricated, the first of which became the Starhopper test article. In February 2019, SpaceX confirmed that the first orbit-capable Starship and Super Heavy test articles would be manufactured nearby, at the "SpaceX South Texas build site."[71] By September 2019, the facility had been completely transformed into a new phase of an industrial rocket build facility, with workers working multiple shifts and more than five days a week, able to support large rocket ground and flight testing.[55] As of November 2019 the SpaceX south Texas Launch Site crew has been working on a new launch pad for its Starship/Super Heavy rocket; the former launch site has been transformed to an assembly site for the Starship rocket.[72]

On 7 March 2021, it was revealed by Michael Baylor on Twitter that the SpaceX South Texas Launch Site may eventually expand to the south. The expansion could see the addition of two suborbital test stands along with one orbital launch pad code-named Orbital Launch Mount B. The expansion could also include a new landing pad, an expansion to the existing tank farm, a new tank farm situated next to the proposed Orbital Launch Mount B, expanded Suborbital Pad B decking and two integration towers situated to under-construction Orbital Launch Mount A and the proposed Orbital Launch Mount B.[73]

In March 2021, SpaceX received a "Determination of no hazard to air navigation" from the FAA for the 146 m (479 ft) launch tower that SpaceX is building that is intended to support orbital launches.[74] The period of construction shown on the FAA documents was April–July 2021 but the expiration date on the regulatory approval was 18 September 2021.[75]

The launch tower was fully stacked by late July 2021, when a crane lifted the ninth and final large steel section to the top of the tower at the orbital launch site (OLS). The tower is designed to have a set of large arms attached which is used to stack both Super Heavy and the Starship second stage on the adjacent launch mount and, eventually, catch the rocket on return to the launch site as well. There is no separate large crane attached to the top of the tower.[76] The launch mount ("Stage Zero") began construction in July 2020 when the rebar of the deep foundation began to rise above the ground. Soon six large steel circular launch supports rose from the ground[77] which would eventually support the massive weight of the launch table some ten months later. The mount was built to full height on 31 July 2021 with the rollout and craning into place of the 370 t (370,000 kg; 820,000 lb) launch table, which had been custom built at the manufacturing site over the preceding months.[76] Musk has commented that Stage Zero would be all that is necessary to both launch and catch the rocket, and that building it is at least as difficult as the booster or ship.[76] As of 2 August 2021, launch mount and launch tower plumbing, electrical, and ground support equipment connections were yet to be completed. Soon after tests for Starships were paused, production started to ramp up for the first orbital test flight. SpaceX workers started building GSE tanks, cryogenic shells, Starship SN20, and Super Heavy Booster 4. As SN20 was completed, and Booster 4 and SN20 were rolled out to the launch site for a full stack. On 6 August 2021, SN20 was stacked on top of Booster 4 for fit checks and compatibility testing with the tower. SpaceX workers soon took SN20 and Booster 4 back to the production site. The launch pad and ground support equipment, including shielding, were completed by April 2023.

On 20 April 2023, Starbase hosted the first launch of the fully stacked Ship 24/Booster 7. The launch ended in an uncontrolled spin due to ignited propellant leaks in the engine control systems, and the rocket's flight termination system detonated four minutes after launch at 39 km (24 miles) altitude, and did not reach the planned suborbital trajectory.[78] Prior to the launch, Musk had said that if the rocket were to get "far enough away from the launchpad before something goes wrong, then I think I would consider that to be a success."[79]

Operation

The South Texas Launch Site is SpaceX's fourth active launch facility, and its first private facility. As of 2019, SpaceX leased three US government-owned launch sites: Vandenberg SLC 4 in California, and Cape Canaveral SLC-40 and Kennedy Space Center LC39A both in Florida.

The launch site is in Cameron County, Texas,[30] approximately 17 miles (27 km) east of Brownsville, with launch flyover range over the Gulf of Mexico.[4] The launch site is planned to be optimized for commercial activity, as well as used to fly spacecraft on interplanetary trajectories.[7]

Launches on orbital trajectories from Brownsville will have a constrained flight path, due to the Caribbean Islands as well as the large number of oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. SpaceX has stated that they have a good flight path available for the launching of satellites on trajectories toward the commercially valuable geosynchronous orbit.[80]

Although SpaceX initial plans for the Boca Chica launch site were to loft robotic spacecraft to geosynchronous orbits, Elon Musk indicated in September 2014 that "the first person to go to another planet could launch from [the Boca Chica launch site]",[81] but did not indicate which launch vehicle might be used for those launches. In May 2018, Elon Musk clarified that the South Texas launch site would be used exclusively for Starship.[5]

By March 2019, two test articles of Starship were being built, and three by May.[82] The low-altitude, low-velocity Starship test flight rocket was used for initial integrated testing of the Raptor rocket engine with a flight-capable propellant structure, and was slated to also test the newly designed autogenous pressurization system that is replacing traditional helium tank pressurization as well as initial launch and landing algorithms for the much larger 9-metre-diameter (29 ft 6 in) rocket.[83] SpaceX developed their reusable booster technology for the 3-meter-diameter Falcon 9 from 2012 to 2018. The Starhopper prototype was also the platform for the first flight tests of the full-flow staged combustion methalox Raptor engine, where the hopper vehicle was flight tested with a single engine in July/August 2019,[84] but could be fitted with up to three engines to facilitate engine-out tolerance testing.[83]

The launch site has been the main production and testing site of the Starship/Super Heavy system. All Starship vehicles have been constructed here except the Mk2 prototype, which was built in Florida but never completed, and eventually scrapped.[85]

By March 2020, SpaceX had doubled the number of employees onsite for Starship manufacturing, test and operations since January, with over 500 employees working at the site. The employees work in four 12-hour shifts distributed throughout the day, with 4 days on, then 3 off for a given week, followed by 3 days on and 4 off for the next—to enable continuous Starship manufacturing with workers and equipment specialized to each task of serial Starship production.[72] A 1 MW solar farm and a 3.8 MWh battery supplies some of the electricity.[86]

In September 2022, during a first test firing of all six engines of the Starship prototype, scattered hot debris ignited a SpaceX dumpster, and caused a bushfire in the nearby Las Palomas Wildlife Management Area, an environmentally sensitive area, ultimately destroying 68 acres before the fire could be doused.[87][88][89]

In May 2023, a few weeks after retiring from NASA, ex-head of human spaceflight Kathy Lueders joined SpaceX to oversee operations at Starbase to "give government customers comfort and confidence that Starship is going to be a *real thing* around which they can base future plans and operations."[90]

On November 11, 2023, SpaceX announced that they were targeting the 17th for their next Starship launch date.[91] They conducted the second integrated flight test successfully on the 18th.

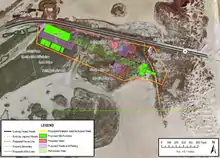

Facilities

Launch site

The launch site is where orbital launching and final testing operations of the Starship spacecraft and Super Heavy boosters occur.

Orbital launch site

The orbital launch site consists of three main components: the orbital tank farm, the orbital launch mount and the integration tower.

The orbital tank farm is home to several horizontal and vertical tanks, which oxygen and methane propellants, as well as nitrogen and water for other uses during testing and launching operations.

The orbital launch mount is where the booster sits above the launch pad and undergoes its static firing testing campaign. The orbital launch mount incorporates systems that provide support to the rocket as well as holding it firmly in place above a massive steel plate with embedded flame deflectors and sound suppression systems in the form of water jets.[92] This steel plate is supplied by a nearby water tank farm that uses compressed gas to propel water to the steel plate under the orbital launch mount.[93] When a launch takes place, the mechanical clamps release to allow the liftoff of the vehicle.

Finally, the integration tower provides fuel and electrical connections to the rocket through quick-disconnect arms, and, in the future, will be responsible for catching Super Heavy as it comes back down to Earth.

Suborbital launch site

The suborbital launch site is where final testing of Starship spacecraft occur.

The suborbital launch site has two test stands, suborbital pad A and suborbital pad B where Starship spacecraft undergo spin-prime and static fire testing.[94] It also includes a smaller tank farm than the orbital launch site to fuel Starship spacecraft during testing operations. Pad A was demolished in late December 2023, however.[95]

The suborbital launch site is also home to a parking lot that was built in early October 2023. It is used for crews working at the launch site.[96]

Production site

The production site, also known as the build site, is where all of the Starship and Super Heavy prototypes are built and assembled.[97]

One of its major components is the Starfactory, a factory which focuses on manufacturing components for the Starship and Super Heavy vehicles. One of the factory's main production ouptut are the steel rings that make up both vehicles. As of November 2023, the Starfactory is seeing some major expansion work done that will, in the long term, allow for mass production of the Starship and Super Heavy elements.

The production site also houses three bays which are responsible for assembling the final vehicles.[98] The High Bay is where Starship second stages are assembled, while the Mega Bay assembles Super Heavy Boosters. As of December 2023, a second Mega Bay is nearing completion.

Sanchez site

The Sanchez site, located within the production site (everything southwest of Remodias Ave), is where construction of many components for infrastructure take place. For example, as of November 2023, it is used to construct stands that will be used to move vehicles are allow for easier installation of Raptor engines on the Super Heavy boosters.[99] Two of those engine installation stands are now placed inside the first Mega Bay.

The Sanchez Site is also home to the rocket garden, which is where boosters and ships awaiting various stages of production are stored. As of November 2023, the rocket garden also houses the ship engine installation stand, where Starship spacecraft receive their three Raptor engines and three Raptor Vacuum engines.

The Sanchez site is so named because SpaceX leases it from Sanchez Oil and Gas Corporation, which had previously used it for natural gas extraction.[100]

Massey's Test Site

The Massey's Test Site is where the majority of SpaceX's design tests take place. The Massey's Test Site is also the primary location for Ship and Super Heavy cryogenic testing. Furthermore, the test site is frequently used for rigorously testing test-tanks and other test articles in order to improve Starship's design.[101] As of November 2023, a new building is in construction at the Massey's Test Site, likely to house office space for crews working at Massey's Test Site.[102] The Massey's site is so named because it was previously the location of "Massey's Gun Shop and Range", before being sold to SpaceX in 2021.[103]

Impact

.jpg.webp)

The new launch facility was projected in a 2014 study to generate US$85 million of economic activity in the city of Brownsville and eventually generate approximately US$51 million in annual salaries from some 500 jobs projected to be created by 2024.[104]

A local economic development board was created for south Texas in 2014—the Cameron County Space Port Development Corporation (CCSPDC)—in order to facilitate the development of the aerospace industry in Cameron County near Brownsville. The first project for the newly established board is the SpaceX project to develop a launch site at Boca Chica Beach.[105] In May 2015, Cameron County transferred ownership of 25 lots in Boca Chica to CCSPDC, which were stated could be used in the future to develop event parking.[106]

Local and economic impact

The launch facility was approved for construction two miles from approximately thirty homes, with no indication that this would cause problems for the homeowners. Five years later in 2019, following an FAA revaluation of the environmental impact[41] and the issuance of new FAA requirements that residents be asked to voluntarily stay outside their houses during particular tanking and engine ignition tests, SpaceX decided that a couple dozen of these homes were too close to the launch facility over the long term and sought acquisition of these properties.[107] An attorney with expertise on such situations referred to the timeframe given[108] by SpaceX for homeowners to consider their purchase offer as "aggressive".[109]

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service claimed that SpaceX had caused 1,000 hours of highway closures in 2019, well above the permitted 300 hours.[110] In June 2021, Cameron County District Attorney Luis Saenz threatened to prosecute SpaceX for unauthorized road and beach closures, as well as employing security officers who may not be licensed to carry handguns.[111][112][113]

During the SN8 launch, SpaceX ignored FAA's models indicating that weather conditions could strengthen shockwave created by rocket explosion and cause damage to nearby homes.[114] SN8 lifted off despite multiple warnings that this would violate company's launch license.[114] Following the launch, the FAA's Associate Administrator Wayne Monteith commented that SpaceX showed poor process discipline by relying on assumptions, as such calling into question company's safety culture.[114] Members of the United States Congress voiced concerns about the FAA's response. However, the FAA Administrator stated that while SpaceX had done several corrections for those violations, the FAA would not approve further flights if SpaceX did not continue to perform those corrections.[115]

A report from the Wall Street Journal in November 2023 found that homeowners, as well as locals in the area, were conflicted with the appearance of Starbase in the vicinity.[116] Some locals stated that they wanted SpaceX to "move on from Cameron County", whereas some locals instead offered a positive view and referred to SpaceX's impact on their economy.[116]

The economic impacts of the spaceport have included an influx of jobs into the area, mostly high-skill, high-wage careers.[117] In addition, The Wall Street Journal found that Musk had plans in place to start a town near SpaceX and Boring Company facilities, dubbed "Snailbrook", wherein its employees would live and work.[118][119] These plans were met with significant backlash and controversy.[120] Additionally, local housing activists had cited concerns about gentrification displacing locals back in May 2022,[121][122][123] with these concerns only resurfacing in light of recent events.[124] The local government has stated that the company boosted the local economy by hiring residents and investing, aiding the three-tenths of the population who live in poverty.[125]

There are also concerns about who will regulate the spaceport, as NASA is not a regulatory agency, and the FAA lacks experience with space travel. As of May 2023, the FAA is overseeing SpaceX's investigation of the April 20 launch and explosion, and had granted one license for that launch only.[78] Whether the space industry will implement plans for Brownsville to become a research center remains unknown.[126]

Environmental reception

Some residents of Boca Chica Village, Brownsville, and environmental activists criticized the Starship development program, stating that SpaceX had harmed local wildlife, conducted unauthorized test flights along with infrastructure construction, and polluted the area with noise.[127][128] Environmental groups warned that the program threatens wildlife in the area, including 18 vulnerable and endangered species.[129] A rare beetle species, the Boca Chica flea beetle, is known only from the beachside dune system next to the launchpad.[130] The spaceport is built under the assumption that the Falcon Heavy rocket would launch there, thus creating a large radius where Starship debris can land on.[131]

Residents of Boca Chica Village and Brownsville, along with environmental activists, have criticized the Starship development program, stating that SpaceX has harmed local wildlife, conducted unauthorized test flights along with infrastructure's construction, and polluted the area with noise.[132][133][134][135] Environmental groups have warned that SpaceX's Starship program threatens wildlife in the area, including 18 vulnerable and endangered species.[136][137] Parts of the wildlife refuge were covered with rocket debris after early failed test launches in 2021 (which took three months to clean up).[136][138] Debris including sand, soil and concrete were spread across the wildlife refuge as far as 5 miles from the launch site again in 2022 after the failed first orbital test flight of Starship, with concerns by environmental groups over further damage to the habitat caused by cleanup efforts.[139]

The Center for Biological Diversity said that Starbase is "surrounded by state parks and national wildlife refuge lands" and include "important habitats for imperiled wildlife" including the critically endangered Kemp's ridley sea-turtle, raising concerns about the impact of Starbase's activities to these habitats and endangered species within.[140][141] Biologists have raised concerns over the impact of Starsbase's noise and light pollution on migratory bird species that use the nearby tidal flats.[142] Stephanie Bilodeau, a conservation bird biologist, said that piping plovers and red knots, both threatened species of birds, have "all but disappeared" from the flats after SpaceX began construction of Starbase in 2021. Additionally, in 2021, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee complained of "unauthorized encroachments and trespass on the refuge" by SpaceX employees.[143]The Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe and environmental activists accused SpaceX of overpolicing the area and disrupting indigenous ceremonies and local fishing.[144]

In 2021, some of the early suborbital hop tests ended in large explosions, causing disruption to residents and wildlife reserves. Residents in the village of Boca Chica had to leave the area prior to each launch due to their proximity.[125] The FAA allowed the public to comment until 1 November 2021 on the environmental impact statement draft that they released on 19 September 2021.[145] SpaceX's environmental assessment missed important details about the propellant source. One such example is SpaceX's plan of building a 250-megawatt gas-fired power plant without specifying how it would obtain tens of millions of cubic feet of gas per day. Pat Parenteau, a law professor and senior counsel for the Environmental Advocacy Clinic at Vermont Law School, stated that it was unusual to exclude such details, which could violate the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act.[146] David Newstead, the director of one local environmental group, said that the explosion of SN11 left rocket debris on parts of the wildlife refuge that took three months to clean up.[143] In May 2022 a 3.5 hectare fire broke out on state parkland as a result of IFT-1.[147] In September 2022 a static-fire test of a Raptor engine by SpaceX caused a 68 acre fire on the protected wildlife reserve, killing wildlife and eventually being contained by firefighters.[148] The blaze occurred in the Las Palomas Wildlife Management Area in the Rio Grande Valley, home to several protected species.[148]

In 2022, following the failed first test launch of Starship, residents of the nearby Port Isabel complained of a "dust" covering homes, cars, and streets.[149] This dust reportedly consisted of fine particles of sand and soil that had been kicked up into the atmosphere from the launch of Starship.[149] According to Dave Cortez of the Sierra Club environmental advocacy group, several residents complained of broken windows in their businesses and the sand/soil particles covering their homes.[150] Spectators of the both the IFT-1 and IFT-2 launches have reportedly caused damage to local habitats in the nearby wildlife reserve, prompting criticism by environmental groups.[151] After reports of damage to tidal flats south of the launchpad following IFT-2 in November 2023, the US Fish and Wildlife Service said that they are working with SpaceX "to educate the public on the importance of tidal flat habitat".[152]

Before the SpaceX Starship orbital test flight on April 20, 2023, 27 organizations including the Sierra Club, South Texas Environmental Justice Network, Another Gulf is Possible, Voces Unidas, Trucha, and the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe signed a letter expressing their concerns and opposition to it. They cited gentrification and overpolicing of the area, wildlife habitat, accessible fishing, and native ceremony disruption, and high risk of explosive and methane-emitting accidents, among others.[153] After the launch, which was plagued by engine fire control issues and forced to end in an explosion via self-destruct over the Gulf,[154] a representative of Another Gulf also criticized the launch's noise levels, blasting of particulate matter (later determined to be sand[155]) on Port Isabel residents 10 km (6.5 miles) away, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's approval that same day of new liquefied natural gas terminals within close proximity of Port Isabel.[156][144] CNBC reported that representatives from the Sierra Club and Center for Biological Diversity said the blast's particulate ejecta (sand[155]) could have negative effects on Port Isabel residents and endangered species' health, and that the blast prevented wildlife biologists from inspecting the area until April 22.[157] The launch scattered debris across 385 acres (156 ha) of SpaceX property and Boca Chica State Park, though no debris was found on refuge fee-owned lands. It also started a wildfire that burned 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) of state park land to the south of the pad. A US Fish and Wildlife Service survey found no evidence of dead birds or other wildlife following the launch,[158] though Texas Public Radio reported that a quail's nest was charred.[159]

On May 1, ten days after the launch, the Tribe and four environmental groups including the Center sued the FAA for allegedly granting the launch license, in the plaintiffs' view, "too early".[160][161][162] SpaceX would later join the FAA as a co-defendant in order to "fight off" the environmental groups' lawsuit over Starship.[163] SpaceX stated the suit could potentially "significantly delay" its Starship program, which in turn would cause "severe injury" to SpaceX's business, the U.S. government, and private customers.[164][165]

SpaceX later built a water deluge system underneath the launch pad from July 5 to July 17, testing it at full pressure for the first time on July 28. However, SpaceX ignored procedures required by state and federal laws, including specifying the water mix's composition, where it will drain into, and how much of it will be used, to apply for permits to test the system.[92] On October 19, the FWS surveyed the area around the Boca Chica launch facility,[166] as well as on October 25, where the water deluge system was taken into account.[167][168]

Starbase had originally planned to launch Falcon rockets when the original environmental assessment was completed in 2014,[10] the site in 2019 was subsequently used to develop Starship and therefore required a revised environmental assessment.[169] In 2021 Pat Parenteau, a law professor and senior counsel for the Environmental Advocacy Clinic at Vermont Law School, commented on the lack of certan details (such as where SpaceX planned on getting it's supply of natural gas) in the FAA's programmatic environmental assessment expressing concerns over potential violations of the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act.[146]

Senator Ted Cruz has said that the second Starship launch was "after months of delay stemming from bureaucratic red tape from AST, Fish and Wildlife and other agencies injecting themselves into the process” resulting in "asinine delays". FAA associate administrator Kelvin Coleman said that the environmental reviews Senator Cruz referred to were required in order to "ensure compliance with NEPA and related environmental laws" and were being conducted in accordance with US law.[170] Environmental protection groups on the other hand have accused regulatory agencies of not doing enough to protect the environment and wildlife in the area surrounding the launch site.[170] In May 2023 several environmental groups sued the FAA and later SpaceX, alleging that the FAA allowed SpaceX to bypass environmental reviews due to Musk's financial and political influence.[141]

Research facilities

The Brownsville Economic Development Council (BEDC) was building a space tracking facility in Boca Chica Village on a 2.3-acre (9,300 m2) site adjacent to the SpaceX launch control center. The STARGATE tracking facility is a joint project of the BEDC, SpaceX, and the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (formerly the University of Texas at Brownsville at the time the agreement was reached).[50]

Tourism

In January 2016, the South Padre Island Convention and Visitors Advisory Board (CVA) recommended that the South Padre Island City Council "proceed with further planning regarding potential SpaceX viewing sites".[171] The spaceport causes beach closures at Boca Chica beach during rocket launches.[172] The closest viewing spots are Rocket Ranch; Isla Blanca Park on South Padre Island; and Port Isabel. Everyday Astronaut warned against crossing the Mexican border because of the dangers of Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[173]

Launches from Starbase in South Texas have attracted SpaceX fans, gathering and taking photos.[174][175] YouTube channels with large followings such as LabPadre or NasaSpaceFlight have been covering Starship's development since 2019, setting up cameras around the launch and production complex and broadcasting 24-hour livestreams.[176]

See also

- List of spaceports

- SpaceX reusable launch system development program

- Starship HLS, lunar variant of the Starship spacecraft developed at the South Texas site

References

- ↑ "NASA chief hails SpaceX's 1st Starship launch despite explosion". Space.com. 20 April 2023.

- ↑ "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". 25 July 2019.

- ↑ "SpaceX launches Starship SN15 rocket and sticks the landing in high-altitude test flight". Space.com. 5 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nield, George C.; et al. (Office of Commercial Space Transportation) (April 2014). "Volume I, Executive Summary and Chapters 1–14" (PDF). Draft Environmental Impact Statement: SpaceX Texas Launch Site (Report). Federal Aviation Administration. HQ-0092-K2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013.

- 1 2 Gleeson, James; Musk, Elon; et al. (10 May 2018). "Block 5 Phone Presser". GitHubGist. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

Our South Texas launch site will be dedicated to BFR, because we get enough capacity with two launch complexes at Cape Canaveral and one at Vandenberg to handle all of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy missions.

- 1 2 3 4 Foust, Jeff (22 September 2014). "SpaceX Breaks Ground on Texas Spaceport". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Under that development schedule, Musk said, the first launch from the Texas site could take place as soon as late 2016.

- 1 2 Clark, Steve (27 September 2014). "SpaceX chief: Commercial launch sites necessary step to Mars". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 Berger, Eric (4 August 2014). "Texas, SpaceX announce spaceport deal near Brownsville". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Elon Musk's Futuristic Spaceport Is Coming to Texas". Bloomberg Businessweek. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- 1 2 Klotz, Irene (11 July 2014). "FAA Ruling Clears Path for SpaceX Launch site in Texas". Space News. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (29 July 2014). "SpaceX, BEDC request building permits". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- 1 2 "SpaceX breaks ground at Boca Chica beach". Brownsville Herald. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (22 October 2015). "Soil headed to Boca Chica for SpaceX". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Foundation Problems Delay SpaceX Launch". KRGV.com/5news. Rio Grande Valley, Texas. 18 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

SpaceX's first launch was set for 2017. The company said the launch site won't be complete until 2017. They anticipate their first launch in 2018.

- ↑ Clark, Steve (13 December 2023). "Starbase general manager discusses future plans at invite-only Brownsville event". MyRGV.com. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ↑ "Texas tries to woo SpaceX on launches". Daily News. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ Mark Hamrick, Elon Musk (29 September 2011). National Press Club: The Future of Human Spaceflight. NPC video repository (video). National Press Club. Event occurs at 32:30. Archived from the original on 15 May 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ "Elon Musk tries to change name of Texas town with a tweet". The Telegraph. 3 March 2021. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ↑ @elonmusk (2 March 2021). "Creating the city of Starbase, Texas" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Mooney, Justin; Bergin, Chris (11 February 2022). "Musk outlines Starship progress towards self-sustaining Mars city". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ↑ "The Gateway to Mars" (PDF). SpaceX.

- ↑ Matthew Hart (9 December 2021). "SpaceX Previews Its 'Gateway to Mars' Texas Launch Site". Nerdist.

- ↑ Aurora Cantu (6 December 2023). "Gateway to Mars sign in Boca Chica". 92.3 MHz FM - The Ranch.

- ↑ Eric Killelea (4 July 2022). "'It's not going to be as sexy': Boca Chica looks toward a SpaceX future less lofty than it'd hoped". San Antonio Express-News. Hearst Newspapers.

- ↑ Dean, James (3 April 2013). "Proposed Shiloh launch complex at KSC debated in Volusia". Florida Today. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Details Emerge on SpaceX's Proposed Texas Launch Site". Space News. 16 April 2012. p. 24.

SpaceX is considering multiple potential locations around the country for a new commercial launch pad. ... The Brownsville area is one of the possibilities.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (13 September 2012). "Sanchez: Texas offering $6M, Florida giving $10M". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ Dickson, Terry (16 November 2012). "Camden County wants to open Georgia's first spaceport". The Florida Times-Union. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (21 February 2023). "Texas is planning to make a huge public investment in space". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- 1 2 Foust, Jeff (1 April 2013). "The great state space race". The Space Review. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

In the best-case scenario, he said, SpaceX would start construction of the spaceport next year, and the first launches from the new facility would take place in two to three years.

- 1 2 Nelson, Aaron M. (5 May 2013). "Brownsville leading SpaceX sweepstakes?". MySanAntonio.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (15 August 2013). "SpaceX buys more land". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ "FAA Notice of Intent to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 3 April 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "SpaceX Proposes New Texas Launch Site". Citizens in Space. 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013.

- 1 2 Martinez, Laura (10 April 2012). "Brownsville area candidate for spaceport". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (25 May 2012). "Texas reaches out to land spaceport deal with SpaceX". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 Perez-Treviño, Emma (20 June 2013). "SpaceX buys more land here". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (23 November 2013). "SpaceX buys more land in Cameron County". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- 1 2 Martinez, Laura B. (19 September 2013). "SpaceX beach closure rules set". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (9 July 2014). "FAA approves SpaceX application to launch rockets from Cameron County beach". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- 1 2 Mosher, Dave (5 September 2019). "New documents reveal SpaceX's plans for launching Mars-rocket prototypes from South Texas". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

The new assessment covers SpaceX's shift away from developing a commercial spaceport and confronts its new reality as a skunkworks for Starship.

- ↑ "Written re-evaluation of the 2014 final environmental impact statement for the Spacex Texas launch site" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 21 May 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

the FAA has concluded that the issuance of launch licenses and/or experimental permits to SpaceX to conduct Starship tests (wet dress rehearsals, static engine fires, small hops, and medium hops) conforms to the prior environmental documentation, that the data contained in the 2014 EIS remain substantially valid, that there are no significant environmental changes, and that all pertinent conditions and requirements of the prior approval have been met or will be met in the current action. Therefore, the preparation of a supplemental or new environmental document is not necessary.

- ↑ "Addendum to the 2019 written re-evaluation for Spacex's reusable launch vehicle experimental test program at the Spacex launch site" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 21 August 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

The proposed experimental test program has progressed to the extent that further operational details can be provided and considered within the context of the 2014 Final Environmental Impact Statement for the SpaceX Texas Launch Site (2014 ElS). This addendum re-evaluates the potential environmental consequences of the updated operational details within the context of the 2014 ElS.

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions Regarding the FAA's Environmental Review of SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Operations at the Boca Chica Launch Site Archived 14 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Aviation Administration, accessed 14 May 2021.

- ↑ Sheetz, Michael (13 June 2022). "FAA requires SpaceX to make environmental adjustments to move forward with its Starship program in Texas". CNBC. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (24 May 2014). "SpaceX buys land". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (19 August 2013). "Cameron County closes two streets for SpaceX". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (6 January 2014). "SpaceX buys more Cameron County land". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (19 February 2014). "SpaceX continues local land purchases". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Perez-Treviño, Emma (25 September 2014). "SpaceX makes more moves". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ "SpaceX still buying land". Valley Morning Star.

- ↑ "The New Residents: Renovation planned for house linked to SpaceX". Valley Morning Star. 29 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ "SpaceX launch pad transforms tiny Texas neighborhood: "Where the hell do I go now?"". CBS News. 18 September 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ↑ "Elon Musk shares SpaceX acquired a Gun Range near Starbase to use the land for rocket testing". TESMANIAN. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- 1 2 Baylor, Michael (21 September 2019). "Elon Musk's upcoming Starship presentation to mark 12 months of rapid progress". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

at SpaceX's launch site in Boca Chica, there was not much more than a mound of dirt [in September 2018 but one year later] the mound of dirt has been transformed into an operational launch site – outfitted with the ground support equipment needed to support test flights of the methane-fueled Starship vehicles.

- ↑ Clark, Steve (4 February 2015). "SpaceX vendor fairs slated". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (14 March 2015). "SpaceX prepping for construction". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- 1 2 Huertas, Tiffany (11 February 2016). "SpaceX working to stabilize land at rocket launch site". CBS4 ValleyCentral.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (6 September 2016). "SpaceX may turn to other launch pads when rocket flights resume". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (4 February 2014). "SpaceX seeks to accelerate Falcon 9 production and launch rates this year". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ↑ Huertas, Tiffany (18 May 2016). "SpaceX construction causing problems for surrounding residents". ValleyCentral.com / KGBT-TV. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- 1 2 Bob Sechler (22 November 2017). "Progress slow at SpaceX's planned spaceport". WSB-TV 2. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ↑ Clark, Steve (13 August 2016). "SpaceX moving two giant antennas to Boca Chica". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019.

- ↑ Pearlman, Robert Z. (2 August 2011). "NASA Closes Historic Antenna Station That Tracked Every Space Shuttle Launch". Space.com News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (6 August 2015). "Solar project planned for SpaceX". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Swanner, Nate (7 August 2014). "SpaceX launch facility goes green, will have solar panel field". Slash Gear. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Rumbaugh, Andrea (11 January 2018). "Aerospace talent in Texas lauded". Houston Chronicle.

SpaceX has a rocket engine testing facility in McGregor and is building a launch site in Boca Chica, said Gwynne Shotwell, president and chief operating officer of SpaceX. The latter project, she said, will be ready late this year or early next year for early vehicle testing. SpaceX will then continue working toward making it a launch site.

- ↑ @BrownsvilleNews (11 July 2018). "A 95,000 gallon @SpaceX liquid oxygen tank is hauled through Brownsville Wednesday to its final destination at the @SpaceX launch site on Boca Chica Beach. Photos by Miguel Roberts #RGV" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Clark, Steve (8 November 2018). "Work picks up in South Texas for SpaceX launch projects". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ↑ Burghardt, Thomas (25 July 2019). "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". NasaSpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ↑ Ralph, Eric (16 February 2019). "SpaceX job posts confirm Starship's Super Heavy booster will be built in Texas". Teslarati. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

fabricators will work to build the primary airframe of the Starship and Super Heavy vehicles at the SpaceX South Texas build site. [They] will work with an elite team of other fabricators and technicians to rapidly build the tank (cylindrical structure), tank bulkheads, and other large associated structures for the flight article design of both vehicles.

- 1 2 Berger, Eric (5 March 2020). "Inside Elon Musk's plan to build one Starship a week—and settle Mars". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ↑ Baylor, Michael (7 March 2021). "Here is the SpaceX Boca Chica launch site construction plan". Twitter. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ↑ "Aeronautical Study No. 2021-ASW-4185-OE : DETERMINATION OF NO HAZARD TO AIR NAVIGATION". faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ↑ "Form 7460-1 for ASN 2021-ASW-4185-OE : obstruction evaluation". faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 Bergin, Chris (2 August 2021). "Starbase Surge sees SpaceX speed ahead with Booster 4 and Ship 20". NasaSpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ Navin, Joseph; Kanayama, Lee (27 August 2020). "Boca work continues as SpaceX marks anniversary of Starhopper's final flight". NasaSpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- 1 2 "FAA grounds SpaceX's Starship rockets after explosion minutes into launch". Politico. 20 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Davenport, Christian (20 April 2023). "SpaceX's Starship lifts off successfully, but explodes in first flight". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ↑ Gwynne Shotwell (21 March 2014). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 03:00–04:05. 2212. Archived from the original (mp3) on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

we are threading the needle a bit, both with the islands as well as the oil rigs, but it is still a good flight path to get commercial satellites to GEO.

- ↑ Solomon, Dan (23 September 2014). "SpaceX Plans To Send People From Brownsville To Mars in Order To Save Mankind". TexasMonthly. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Baylor, Michael (17 May 2019). "SpaceX considering SSTO Starship launches from Pad 39A". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- 1 2 Gebhardt, Chris (3 April 2019). "Starhopper conducts Raptor Static Fire tests". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ Burghardt, Thomas (25 July 2019). "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ @julia_bergeron (22 July 2020). "Going, going, almost gone. Progress continues on MK2 today in Cocoa, FL. A flatbed truck entered the facility presumably to haul away more scrap. As of this morning both nosecone sections remain on site" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020 – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Tesla supplying Power Pack for SpaceX Starbase 8MWh BESS expansion". Energy Storage News. 5 May 2022.

- ↑ "Fire at SpaceX launch site burns 68 acres at protected refuge killing wildlife". news.yahoo.com. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ Ralph, Eric (9 September 2022). "SpaceX Starship prototype ignites six engines, starts major brush fire". TESLARATI. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ "SpaceX Starship Prototype Belches Superhot Debris, Causes Literal Dumpster Fire". Gizmodo. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ Sheetz, Michael (15 May 2023). "SpaceX hires former NASA human spaceflight official Kathy Lueders to help with Starship". CNBC. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ↑ @SpaceX (11 November 2023). "Starship preparing to launch as early as November 17, pending final regulatory approval → http://spacex.com/launches" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- 1 2 Kolodny, Lora (28 July 2023). "SpaceX hasn't obtained environmental permits for 'flame deflector' system it's testing in Texas". CNBC. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ↑ How SpaceX Will Guarantee Its Launch Pad Never Fails Again! [Part 2], retrieved 7 October 2023

- ↑ SpaceX is pushing HARD towards the next Starship launch!, retrieved 23 June 2023

- ↑ Suborbital Pad A Scrapping Begins | SpaceX Boca Chica, retrieved 22 December 2023

- ↑ SpaceX Delays EXPLAINED! - Starbase Flyover Update Episode 21, retrieved 24 October 2023

- ↑ Starbase 101: A Tour of the SpaceX Starship Rocket Production and Launch Facilities 2023, retrieved 23 June 2023

- ↑ How Does SpaceX Build Starships at Starbase? From Steel to Starship., retrieved 23 June 2023

- ↑ Next Ship Prepped for Testing! Starbase Flyover Update 18, retrieved 7 October 2023

- ↑ Lingle, Brandon (27 May 2021). "SpaceX battling oil company over land". MySA. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ Starbase Isn't Slowing Down! | SpaceX Starbase Update, retrieved 27 September 2023

- ↑ SpaceX's CRUCIAL Test Article, S26 Ready to Fire? - Starbase Flyover Update Episode 20, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ↑ Moreno, Gaby (14 June 2021). "Massey's Gun Shop and Range sell property to SpaceX". KVEO-TV. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ Jervis, Rick (6 October 2014). "Texas border town to become next Cape Canaveral". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Long, Gary (30 July 2014). "Board meets regarding SpaceX project". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (10 May 2015). "Expanding the future". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Flahive, Paul (26 September 2019). "SpaceX Squares Off Against Homeowners Near Texas Launch Facility". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ↑ ""Great Job": ISRO On Historic NASA, SpaceX Mission". The Indian Hawk. June 2020. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ↑ Masunaga, Samantha (1 October 2019). "To reach Mars, SpaceX is trying to buy up a tiny Texas community". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ↑ "SpaceX launch site brings controversy to Texas town". CBS News. 17 August 2021. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ Wattles, Jackie (17 June 2021). "Texas authorities threaten SpaceX with legal action over beach closures, private security". CNN Business. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ De La Garza, Erik (26 June 2021). "Threatened With Prosecution, SpaceX Defends Its Activities in South Texas". Courthouse News Service. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ B. Martinez, Laura (15 June 2021). "Cameron County DA: SpaceX may be violating Texas law". MyRGV.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Roulette, Joey (15 June 2021). "SpaceX ignored last-minute warnings from the FAA before December Starship launch". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ↑ "Congress raises concerns about FAA's handling of Starship launch license violation". SpaceNews. 29 March 2021. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- 1 2 Maidenberg, Micah (26 November 2023). "Humanity's Future or an Unwelcome Interloper: SpaceX's Starbase Transforms a Corner of Texas". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ↑ Lowry, Willy (29 June 2022). "On the cusp of history: a small Texas city adapts to life with Elon Musk and SpaceX". The National. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Kirsten Grind, Rebecca Elliot, Ted Mann, Julie Bykowicz (9 March 2023). "Elon Musk Is Planning a Texas Utopia—His Own Town". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Duffy, Clare (9 March 2023). "The Wall Street Journal: Elon Musk is planning to build his own town". CNN. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ↑ Koren, Marina (27 April 2023). "The Messy Reality of Elon Musk's Space City". The Atlantic. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ↑ Davila, Dave (13 May 2022). "Housing costs skyrocket as SpaceX expands in Texas city". NPR.

- ↑ "The Fine Print: Exploring Musk's Impact, Local Leaders' Complacency, and the Community's Struggle - Trucha RGV". 24 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Duffy, Kate. "SpaceX is causing a rift between Brownsville residents. Some say it's shattering the lives of locals but others are welcoming the economic boom it's created". Business Insider. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Rose, Steve (18 April 2023). "Is Elon Musk creating a utopian city? The hellish, heavenly history of company towns". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- 1 2 Sandoval, Edgar; Webner, Richard (24 May 2021). "A Serene Shore Resort, Except for the SpaceX 'Ball of Fire'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ "'It's Not Going To Be as Sexy': Boca Chica Looks Toward a SpaceX Future Less Lofty Than it'd Hoped". Aviation Pros. 5 July 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Sheetz, Michael (14 July 2021). "FAA warns SpaceX that massive Starship launch tower in Texas is unapproved". CNBC. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ Koren, Marina (11 February 2020). "Why SpaceX Wants a Tiny Texas Neighborhood So Badly". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ Wray, Dianna (5 September 2021). "Elon Musk's SpaceX launch site threatens wildlife, Texas environmental groups say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ↑ "Species Chaetocnema rileyi". bugguide.net. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ↑ "SpaceX's monstrous, dirt-cheap Starship may transform space travel". The Economist. 19 February 2022. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ Sheetz, Michael (14 July 2021). "FAA warns SpaceX that massive Starship launch tower in Texas is unapproved". CNBC. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ Koren, Marina (11 February 2020). "Why SpaceX Wants a Tiny Texas Neighborhood So Badly". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ Burnett, John (21 June 2021). "SpaceX's New Rocket Factory Is Making Its Texas Neighbors Mad". NPR. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ↑ Webner, Richard (13 July 2021). "'It just shouldn't be going on here'; Brownsville activists say Elon Musk's SpaceX spaceport damaging wildlife habitat". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- 1 2 Wray, Dianna (5 September 2021). "Elon Musk's SpaceX launch site threatens wildlife, Texas environmental groups say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ↑ De La Garza, Erik (28 July 2021). "As SpaceX races to expand launch site, concern grows for wildlife habitats in South Texas". Courthouse News. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ↑ De La Rosa, Pablo (13 May 2021). "As SpaceX Ramps Up Activity In The Rio Grande Valley, Local Concerns Grow". TPR. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ↑ Nilsen, Jackie Wattles,Ella (1 May 2023). "Environmental groups sue FAA for SpaceX launch that exploded in April". CNN. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑

- 1 2

- ↑ Burnett, John (21 June 2021). "SpaceX's New Rocket Factory Is Making Its Texas Neighbors Mad". NPR. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- 1 2 "SpaceX launch site brings controversy to Texas town". CBS News. 17 August 2021. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- 1 2 ""Colonizing Our Community": Elon Musk's SpaceX Rocket Explodes in Texas as Feds OK New LNG Projects". Democracy Now!. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ↑ Shepardson, David (30 September 2021). "U.S. extends environmental review for SpaceX program in Texas". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- 1 2 "The mystery of Elon Musk's missing gas". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ↑ Nilsen, Jackie Wattles,Ella (1 May 2023). "Environmental groups sue FAA for SpaceX launch that exploded in April". CNN. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Fire at SpaceX launch site burns 68 acres at protected refuge killing wildlife". Yahoo News. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- 1 2 Panella, Rebecca Cohen, Chris. "SpaceX's Starship launch kicked up soil and sand that rained down on a nearby beachside town 5 miles away". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ben Turner (25 April 2023). "Disastrous SpaceX launch under federal investigation after raining potentially hazardous debris on homes and beaches". livescience.com. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ↑ "SpaceX sued by environmental groups, again, claiming rockets harm critical Texas bird habitats". USA TODAY. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ↑

- ↑ "Press Statement: Rio Grande Valley Community React Ahead of SpaceX Rocket Launch Blast on the South Texas Coastline" (PDF). Sierra Club. 19 April 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (8 September 2023). "FAA says SpaceX has more to do before Starship can fly again". Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- 1 2 Leinfelder, Andrea (2 August 2023). "SpaceX Starship sprinkled South Texas with mystery material. Here's what it was". Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Albeck-Ripka, Livia (21 April 2023). "SpaceX's Starship Kicked Up a Dust Cloud, Leaving Texans With a Mess". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ↑ Kolodny, Lora (24 April 2023). "SpaceX Starship explosion spread particulate matter for miles". CNBC. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ↑ Grush, Loren; Hull, Dana (26 April 2023). "SpaceX's Starship Launch Sparked Fire on State Park Land". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ↑ Davila, Gaige (27 April 2023). "SpaceX is grounded after rocket explosion caused extensive environmental damage". Texas Public Radio. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ Center for Biological Diversity et al. v. Federal Aviation Administration (D.C. Cir. 2023), Text.

- ↑ Kolodny, Lora (1 May 2023). "FAA sued over SpaceX Starship launch program following April explosion". CNBC – via NBC News.

- ↑ Gorman, Steve (1 May 2023). "Environmentalists sue FAA over SpaceX launch license for Texas". Reuters. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (23 May 2023). "SpaceX joining FAA to fight environmental groups' Starship lawsuit: report". Space.com. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ↑ Killelea, Eric (23 May 2023). "SpaceX joins FAA as defendant in lawsuit over private space company's launch from South Texas". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ↑ Michael Sheetz, Lora Kolodny (22 May 2023). "SpaceX set to join FAA to fight environmental lawsuit that could delay Starship work". CNBC. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ↑ LabPadre Space (19 October 2023). "LabPadre Space on X: "Fish and Wildlife Service is surveying the area around the Launch Site. Come tune in and watch live"". Twitter. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ "twitter.com/nasaspaceflight/status/1717163473400926410". X (formerly Twitter). Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ↑ George Dvorsky (27 October 2023). "Review of SpaceX Starship's Water Deluge System Critical to Next Launch". Gizmodo. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ↑ Kramer, Anna (7 September 2021). "SpaceX's launch site may be a threat to the environment". Protocol.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- 1 2 Foust, Jeff (15 December 2023). "Federal agencies caught in environmental crossfire over Starship launches". SpaceNews. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ↑ Kunkle, Abbey (15 January 2016). "City moves forward with viewing facility". Port Isabel-South Padre Press. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ "SpaceX". Cameron County. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ DeSisto, Austin (4 April 2023). "How To Visit Starbase". Everyday Astronaut. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ↑ Lingle, Brandon (17 November 2023). "'Bigger than Woodstock': SpaceX fans congregate in South Texas to watch, wait for Starship launch". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Josh Dinner (17 November 2023). "These SpaceX fans say they'll stay after 1-day Starship launch delay to Saturday". Space.com. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (13 September 2022). "Encounters with SpaceX fans who uprooted their lives and moved to Starbase". The Verge. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

External links

- SpaceX gets preliminary FAA nod for South Texas launch site, Waco Tribune-Herald, 16 April 2013.

- Lone Star State Bets Heavily on a Space Economy, New York Times, 27 November 2014.