Southend-on-Sea

City of Southend-on-Sea | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Southend Civic Centre, St Marys Church Parish Church, Southend Pier, Southend-on-Sea City aerial view, and the Crowstone | |

Southend-on-Sea City Council (Civic arms of Southend-on-Sea) | |

| Motto(s): Per Mare Per Ecclesiam (By Sea, By Church) | |

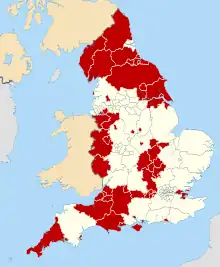

Shown within Essex | |

| Coordinates: 51°33′N 0°43′E / 51.55°N 0.71°E | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | East of England |

| Ceremonial county | Essex |

| Admin HQ | Southend-on-Sea |

| Areas of the city | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Leadership | Leader & Cabinet (Labour) |

| • Governing Body | Southend-on-Sea City Council |

| • Executive | Conservative (council NOC) |

| • MPs | Anna Firth (C) James Duddridge (C) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 16.12 sq mi (41.76 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | Ranked 115th 180,601 |

| • Density | 11,230/sq mi (4,334/km2) |

| • Ethnicity[1] | 93.6% White 2.5% S.Asian 1.5% Black 1.4% Mixed Race |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode | |

| Post town | southend-on-sea |

| Dialling code | 01702 |

| Grid reference | TQ883856 |

| ONS code | 00KF (ONS) E06000033 (GSS) |

| Website | www.southend.gov.uk |

Southend-on-Sea (/ˌsaʊθɛndɒnˈsiː/ ⓘ), commonly referred to as Southend (/saʊˈθɛnd/), is a coastal city and unitary authority area with borough status in southeastern Essex, England. It lies on the north side of the Thames Estuary, 40 miles (64 km) east of central London. It is bordered to the north by Rochford and to the west by Castle Point. It is home to the longest pleasure pier in the world, Southend Pier.[2] London Southend Airport is located north of the city centre.

Southend-on-Sea originally consisted of a few poor fishermen's huts and farms at the southern end of the village of Prittlewell. In the 1790s, the first buildings around what was to become the High Street of Southend were completed. In the 19th century, Southend's status as a seaside resort grew after a visit from Princess Caroline of Brunswick, and Southend Pier was constructed. From the 1960s onwards, the city declined as a holiday destination. Southend redeveloped itself as the home of the Access credit card, due to its having one of the UK's first electronic telephone exchanges. After the 1960s, much of the city centre was developed for commerce and retail, and many original structures were lost to redevelopment. An annual seafront airshow, which started in 1986 and featured a flypast by Concorde, used to take place each May until 2012.

On 18 October 2021, it was announced that Southend would be granted city status, as a memorial to the Member of Parliament for Southend West, Sir David Amess, a long-time supporter of city status for the borough, who was murdered on 15 October 2021.[3][4] Southend was granted city status by letters patent dated 26 January 2022. On 1 March 2022, the letters patent were presented to Southend Borough Council by Charles, Prince of Wales.[5][6]

History

Originally the "south end" of the village of Prittlewell, Southend was home to a few poor fishermen's huts and farms at the southern extremity of Prittlewell Priory land. In the 1790s, landowner Daniel Scratton sold off land on either side of what was to become the High Street. The Grand Hotel (now Royal Hotel) and Grove Terrace (now Royal Terrace) were completed by 1794, and stagecoaches from London made it accessible.[7] Due to the bad transportation links between Southend and London, there was not rapid development during the Georgian Era as there was in Brighton, although Southend is mentioned in Jane Austen's novel Emma of 1815. However, after the coming of the railways in the 19th century and the visit of Princess Caroline of Brunswick, Southend's status as a seaside resort grew. During the 19th century, Southend's pier was first constructed and the Clifftown development built,[8] attracting many summer tourists to its seven miles of beaches and sea bathing. Good rail connections and proximity to London mean that much of the economy has been based on tourism and that Southend has been a dormitory town for city workers ever since. Southend Pier is the world's longest pleasure pier at 1.34 mi (2.16 km).[2] It has suffered fires and ship collisions, most recently in October 2005,[9] but the basic pier structure has been repaired each time.

As a holiday destination, Southend declined from the 1960s onwards, as holidaying abroad became more affordable. Southend became the home of the Access credit card, as it had one of the UK's first electronic telephone exchanges (it is still home to RBS Card Services – one of the former members of Access), with offices based in the former EKCO factory, Maitland House (Keddies), Victoria Circus and Southchurch Road. Since then, much of the city centre has been developed for commerce and retail, and during the 1960s many original structures were lost to redevelopment – such as the Talza Arcade and Victoria Market (replaced by what is now known as The Victoria Shopping Centre) and Southend Technical College (on the site of the ODEON Cinema, now a campus of South Essex College).[10] However, about 6.4 million tourists still visit Southend per year, generating estimated revenues of £200 million a year. H.M. Revenue & Customs (HMRC), (formerly H.M. Customs and Excise), were major employers in the city, and the central offices for the collection of VAT were located at Alexander House on Victoria Avenue. Staff were finally relocated to Stratford in December 2022.

An annual seafront airshow, started in 1986 when it featured a flypast by Concorde whilst on a passenger charter flight, used to take place each May and became one of Europe's largest free airshows. The aircraft flew parallel to the seafront, offset over the sea. The RAF Falcons parachute display team and RAF Red Arrows aerobatics team were regular visitors to the show. The last show was held in 2012; an attempt to revive the show for September 2015, as the Southend Airshow and Military Festival, failed.[11]

On 15 October 2021, the Member of Parliament for Southend West, Sir David Amess, was fatally stabbed during a constituency meeting in Leigh-on-Sea. On 18 October 2021, the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced that the Queen had agreed to grant Southend-on-Sea with city status as a memorial to Amess, who had long campaigned for this status to be granted.[3] Preparations, led by Amess, for Southend to enter a competition for city status in 2022 as part of the Queen's Platinum Jubilee were underway at the time of his death.[12][13] A "City Week" was held throughout the town between 13 and 20 February 2022,[14] beginning with the inaugural "He Built This City" concert named in honour of Amess.[15][16] The concert was held at the Cliffs Pavilion and included performers such as Digby Fairweather, Lee Mead, and Leanne Jarvis.[17] Other events such as a city ceremony and the Southend LuminoCity Festival of Light were held during the week. Sam Duckworth, who knew Amess personally, performed at some of the events.[16] On 1 March, Southend Borough Council was presented letters patent from the Queen, by Charles, Prince of Wales, officially granting the borough city status.[5] Southend became the second city in the ceremonial county of Essex, after Chelmsford, which was granted city status in 2012.[18]

Governance

There is just one tier of local government covering Southend. The city council performs the functions of both a county and district council, being a unitary authority. There is one civil parish within the city at Leigh-on-Sea; the rest of the city is an unparished area.[19][20]

Administrative history

Southend's first elected council was a local board, which held its first meeting on 29 August 1866.[21] Prior to that the town was administered by the vestry for the wider parish of Prittlewell. The local board district was enlarged in 1877 to cover the whole parish of Prittlewell.[22]

The town was made a municipal borough in 1892. In 1897 the borough was enlarged to also include the neighbouring parish of Southchurch.[23] The borough was enlarged again in 1913 to take in the former Leigh on Sea Urban District. In 1914 the enlarged Southend became a county borough making it independent from Essex County Council and a single-tier of local government. The county borough was enlarged in 1933 by the former area of Shoeburyness Urban District and part of Rochford Rural District.

On 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, Southend became a district of Essex, with the county council once more providing county-level services to the town. However, in 1998 it again became the single tier of local government when it became a unitary authority.[24]

Upon receiving city status on 1 March 2022, the council voted to rename itself 'Southend-on-Sea City Council'.[5]

The Latin motto, 'Per Mare Per Ecclesiam', emblazoned on the municipal coat of arms, translates as 'By [the] Sea, By [the] Church', reflecting Southend's position between the church at Prittlewell and the sea as in the Thames estuary. The city has been twinned with the resort of Sopot in Poland since 1999[25] and has been developing three-way associations with Lake Worth Beach, Florida.

Southend Civic Centre was designed by borough architect, Patrick Burridge, and officially opened by the Queen Mother on 31 October 1967.[26]

Members of Parliament

Southend is represented by two Members of Parliament (MPs) at Westminster.

The MP for Southend West was Sir David Amess (Conservative), who served from 1997 until his murder in 2021. Anna Firth has served as the MP for the constituency since the following 2022 Southend West by-election.

Since 2005 the MP for Rochford and Southend East has been James Duddridge (Conservative), who replaced Sir Teddy Taylor. Despite its name the majority of the constituency is in Southend, including the centre of the city; Rochford makes up only a small part and the majority of Rochford District Council is represented in the Rayleigh constituency.

Demography

Southend is the seventh most densely populated area in the United Kingdom outside of the London Boroughs, with 38.8 people per hectare compared to a national average of 3.77. By 2006, the majority, or 52% of the Southend population were between the ages of 16–54, 18% were below age 15, 18% were above age 65 and the middle age populace between 55 and 64 accounted for the remaining 12%.[27]

Save the Children's research data shows that for 2008–09, Southend had 4,000 children living in poverty, a rate of 12%, the same as Thurrock, but above the 11% child poverty rate of Essex as a whole.[28]

The Department for Communities and Local Government's 2010 Indices of Multiple Deprivation Deprivation Indices data showed that Southend is one of Essex's most deprived areas. Out of 32,482 Lower Super Output Areas in England, area 014D in the Kursaal ward is 99th, area 015B in Milton ward is 108th, area 010A in Victoria ward is 542nd, and area 009D in Southchurch ward is 995th, as well as an additional 5 areas all within the top 10% most deprived areas in England (with the most deprived area having a rank of 1 and the least deprived a rank of 32,482).[29] Victoria and Milton wards have the highest proportion of ethnic minority residents – at the 2011 Census these figures were 24.2% and 26.5% respectively. Southend has the highest percentage of residents receiving housing benefits (19%) and the third highest percentage of residents receiving council tax benefits in Essex.

The urban area of Southend spills outside of the borough boundaries into the neighbouring Castle Point and Rochford districts, including the towns of Hadleigh, Benfleet, Rayleigh and Rochford, as well as the villages of Hockley and Hullbridge. According to the 2011 census, it had a population of 295,310,[30] making it the largest urban area solely within the East of England.[31]

Economy

This is a chart of the trend of regional gross value added of Southend-on-Sea at current basic prices published (pp. 240–253) by Office for National Statistics with figures in millions of British Pounds Sterling.

| Year | Regional Gross Value Added[32] | Agriculture[33] | Industry[34] | Services[35] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1,373 | 2 | 305 | 1,066 |

| 2000 | 1,821 | 1 | 375 | 1,445 |

| 2003 | 2,083 | – | 418 | 1,665 |

In 2006, travel insurance company InsureandGo relocated its offices from Braintree to Maitland House in Southend-on-Sea. The company brought 120 existing jobs from Braintree and announced the intention to create more in the future.[36] However the business announced the plan to relocate to Bristol in 2016.[37] The building is now home to Ventrica, a customer service outsourcing company.[38][39]

Southend has industrial parks located at Progress Road, Comet and Aviation Ways in Eastwood and Stock Road in Sutton. Firms located in Southend include Olympus Keymed, Hi-Tec Sports and MK Electric. Southend has declined as a centre for credit card management with only Royal Bank of Scotland card services (now branded NatWest) still operating in the city.[40]

A fifth of the working population commutes to London daily. Wages for jobs based in Southend were the second lowest among UK cities in 2015. It also has the fourth-highest proportion of people aged over 65. This creates considerable pressure on the housing market. It is the 11th most expensive place to live in Britain.[41]

Southend-on-Sea County Borough Corporation has provided the borough with electricity since the early twentieth century from the Southend power station. Upon nationalisation of the electricity industry in 1948 ownership passed to the British Electricity Authority and later to the Central Electricity Generating Board. Electricity connections to the national grid rendered the 5.75 megawatt (MW) power station redundant. Electricity was generated by diesel engines and by steam obtained from the exhaust gases. The power station closed in 1966; in its final year of operation, it delivered 2,720 MWh of electricity to the borough.[42]

Transport

Airport

London Southend Airport was developed from the military airfield at Rochford; it was opened as a civil airport in 1935. It now offers scheduled flights to destinations across Europe, corporate and recreational flights, aircraft maintenance and training for pilots and engineers. It is served by Southend Airport railway station, on the Shenfield–Southend line, part of the Great Eastern Main Line.

Buses

%252C_2009_Clacton_Bus_Rally.jpg.webp)

Local bus services are provided by two main companies. Arriva Southend was formerly the council-owned Southend Corporation Transport and First Essex Buses was formerly Eastern National/Thamesway. Smaller providers include Stephensons of Essex.

Southend has a bus station on Chichester Road, which was developed from a temporary facility added in the 1970s; the previous bus station was located on London Road and was run by Eastern National, but it was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a Sainsbury's supermarket.[43] Arriva Southend is the only bus company based in Southend, with their depot located in Short Street; it was previously sited on the corner of London Road and Queensway and also a small facility in Tickfield Road.[44] First Essex's buses in the Southend area are based out of the depot in Hadleigh but, prior to the 1980s, Eastern National had depots on London Road (at the bus station) and Fairfax Drive.[45]

Railway

A c2c train at Southend Central station

A c2c train at Southend Central station Southend Victoria station

Southend Victoria station Southend Cliff Railway

Southend Cliff Railway

Southend is served by two lines on the National Rail network:

- Running from Southend Victoria north out of the city is the Shenfield–Southend line, a branch of the Great Eastern Main Line, operated by Abellio Greater Anglia. Services operate to London Liverpool Street, via Shenfield.

- Running from Shoeburyness, in the east of the borough, is the London, Tilbury and Southend line operated by c2c. It runs west through Thorpe Bay, Southend East, Southend Central to London Fenchurch Street, either via Benfleet and Basildon or Tilbury Town and Barking. Additionally, one service from Southend Central each weekday evening terminates at Liverpool Street.

From 1910 to 1939, the London Underground's District line's eastbound service ran as far as Southend and Shoeburyness.[46]

Besides its main line railway connections, Southend is also the home of two smaller railways. The Southend Pier Railway provides transport along the length of Southend Pier, whilst the nearby Southend Cliff Railway provides a connection from the promenade to the cliff top above.[47]

Roads

Two A-roads connect Southend with London and the rest of the country: the A127 (Southend Arterial Road), via Basildon and Romford, and the A13, via Thurrock and London Docklands. Both are major routes; however, within the borough, the A13 is now a single carriageway local single-carriageway route, whereas the A127 is an entirely dual-carriageway. Both connect to the M25 and eventually London.

Climate

Southend-on-Sea is one of the driest places in the UK. It has a marine climate with summer highs of around 22 °C (72 °F) and winters highs being around 7.8 °C (46.0 °F).[48] Summer temperatures are generally slightly cooler than those in London. Frosts are occasional. During the 1991–2020 period there was an average of 29.6 days of air frost. Rainfall averaged 527 millimetres (20.7 in). Weather station data is available from Shoeburyness,[48] which is adjacent to Southend in the eastern part of the urban area.

| Climate data for Shoeburyness, in eastern part of Southend Urban Area, 2m asl, 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.0 (1.69) |

36.1 (1.42) |

32.7 (1.29) |

36.1 (1.42) |

41.6 (1.64) |

44.1 (1.74) |

41.1 (1.62) |

48.6 (1.91) |

43.0 (1.69) |

57.8 (2.28) |

54.0 (2.13) |

48.8 (1.92) |

526.9 (20.75) |

| Average rainy days | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 101.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.5 | 88.9 | 136.8 | 200.4 | 241.2 | 243.3 | 257.0 | 212.2 | 162.4 | 130.0 | 84.7 | 56.9 | 1,884.3 |

| Source: Met Office[49] | |||||||||||||

Education

University of Essex accommodation in Southend

University of Essex accommodation in Southend Cecil Jones Academy

Cecil Jones Academy

South Essex College Southend Campus

South Essex College Southend Campus Southend Adult Community College

Southend Adult Community College

Secondary schools

All mainstream secondary schools are mixed-sex comprehensives, including Belfairs Academy; Cecil Jones Academy; Chase High School; Southchurch High School; Shoeburyness High School and The Eastwood Academy.

In 2004, Southend retained the grammar school system and has four such schools: Southend High School for Boys; Southend High School for Girls; Westcliff High School for Boys and Westcliff High School for Girls.

Additionally, there are two single-sex schools assisted by the Roman Catholic Church: St Bernard's High School (girls) and St Thomas More High School (boys). Both, while not grammar schools, contain a grammar stream; entrance is by the same exam as grammar schools.

Further and higher education

The main higher education provider in Southend is the University of Essex which has a campus in Elmer Approach on the site of the former Odeon cinema. It also operates the East 15 Acting School Southend campus at the Clifftown Theatre.[50]

In addition to a number of secondary schools that offer further education, the largest provider is South Essex College in a purpose-built building in the centre of town. Formerly known as South East Essex College, (and previously Southend Municipal College) the college changed name in January 2010 following a merger with Thurrock and Basildon College.[51]

Additionally there is PROCAT that is based at Progress Road, while learners can travel to USP College (formerly SEEVIC College) in Thundersley. The East 15 Acting School, a drama school has its second campus in Southend, while the Southend Adult Community College is in Ambleside Drive. Southend United Futsal & Football Education Scholarship, located at Southend United's stadium Roots Hall, provides education for sports scholarships.

Sport

Southend has two football teams, one of professional stature, Southend United. United currently competes in the Vanarama National League. The other, Southend Manor, plays in the Essex Senior League.

There are two rugby union clubs Southend RFC which play in London 1 North and Westcliff R.F.C. who play in London & South East Premier. Southend was formerly home to the Essex Eels rugby league team. Southend was home to the Essex Pirates basketball team that played in the British Basketball League between 2009 and 2011.

Essex County Cricket Club plays in Southend one week a season. Previously the festival was held at Chalkwell Park and most recently Southchurch Park, but it has now moved to Garons Park next to the Southend Leisure & Tennis Centre. The only other cricket is local.

The Old Southendians Hockey Club is based at Warner's Bridge in Southend.

The eight-lane, floodlit, synthetic athletics track at Southend Leisure and Tennis Centre is home to Southend-on-Sea Athletic Club. The facilities cover all track and field events.[52] The centre has a 25m swimming pool and a world championship level diving pool with 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10m boards, plus springboards with the only 1.3m in the UK.[53]

Entertainment and culture

Southend Pleasure Pier

Southend-on-Sea is home to the world's longest pleasure pier, built in 1830 and stretching some 1.34 miles (2.16 km) from shore.[54]

Kursaal

The Kursaal was one of the earliest theme parks, built at the start of the 20th century. It closed in the 1970s and much of the land was developed as housing. The entrance hall, a listed building, used to house a bowling alley arcade operated by Megabowl and casino, however the bowling alley closed in 2019 and the casino closed in 2020. The building currently stands unused.

Southend Carnival

Southend Carnival has been an annual event since 1906, where it was part of the annual regatta, and was set up to raise funds for the Southend Victoria Cottage Hospital. In 1926, a carnival association was formed, and by 1930, they were raising funds for the building of the new General Hospital with a range of events, including a fete in Chalkwell Park.[55][56] The parades, which included a daylight and torchlight parades were cut down to just a torchlight parade during the 1990s.

Cliff Lift

A short funicular railway, constructed in 1912, links the seafront to the High Street level of the town. The lift re-opened to the public in 2010, following a period of refurbishment.[57]

Other seafront attractions

An amusement park Adventure Island, formerly known as Peter Pan's Playground, straddles the pier entrance. The seafront houses the "Sea-Life Adventure" aquarium.

The cliff gardens, which included Never Never Land and a Victorian bandstand were an attraction until slippage in 2003 made parts of the cliffs unstable. The bandstand has been removed and re-erected in Priory Park. Beaches include Three Shells and Jubilee Beach.

A modern vertical lift links the base of the High Street with the seafront and the new pier entrance. The older Southend Cliff Railway, a short funicular, is a few hundred metres away.

The London to Southend Classic Car Run takes place each summer. It is run by the South Eastern Vintage and Classic Vehicle Club and features classic cars which line the seafront.[58]

The Southend Shakedown, organised by Ace Cafe, is an annual event featuring motorbikes and scooters. There are other scooter runs throughout the year, including the Great London Rideout, which arrives at Southend seafront each year.[59]

Festival events

The Southend-on-Sea Film Festival is an annual event that began in 2009 and is run by the White Bus film and theatrical company based at The Old Waterworks Arts Center located inside a Victorian era Old Water Works plant. Ray Winstone attended the opening night gala in both 2010 and 2011, and has become the Festival Patron.[60]

Since 2021, the city has hosted a Halloween parade in October, while the Leigh Art Trail runs during July. Two events that started in 2022 was Southend City Jam, a street art festival, and LuminoCity, a light festival,[61] however LuminoCity was announced to be cancelled for 2024 due to budget cuts at Southend City Council.[62] The Old Leigh Regatta takes place every September,[63] while Leigh Folk Festival has run since 1992, though will be taking a break in 2024.[64] The Southend Jazz Festival has been run since 2020.[65]

Between 2008 and 2019, Chalkwell Park became home to the Village Green Art & Music Festival for a weekend every July,[66] but has not run since 2019 due to covid.

Shopping

Southend High Street runs from the top of Pier Hill in the South, to Victoria Circus in the north. It currently has two shopping centres – the Victoria (built during the 1960s and a replacement for the old Talza Arcade, Victoria Arcade and Broadway Market)[67] and The Royals Shopping Centre (built late 1980s and opened in March 1988 by actor Jason Donovan, replacing the bottom part of High Street, Grove Road, Ritz Cinema and Grand Pier Hotel).[68] Southend High Street has many chain stores, with Boots in the Royals, and Next anchoring the Victoria.[69]

This was not always the case with many independent stores closing in the 1970s and 1980s – Keddies (department store), J F Dixons (department store), Brightwells (department store), Garons (grocers, caterers and cinema),[70][71] Owen Wallis (ironmongers and toys),[72] Bermans (sports and toys),[73] J Patience (photographic retailers)[74] & R. A. Jones (jewellers) being the most notable. One of Southend's most notable business, Schofield and Martin, was purchased by Waitrose in 1944 with the name being used until the 1960s. The Alexandra Street branch was the first Waitrose store in 1951 to be made self-service.[75] Southend is home to the largest store in the Waitrose portfolio.

The longest surviving independent retail business in Southend was Ravens which operated from 1897 to 2017.[76] A Southend business that started in 1937 and is still active in 2022 is Dixons Retail.[77][78][79]

The city of Southend has shopping in other areas. Leigh Broadway and Leigh Road in Leigh-on-Sea, Hamlet Court Road in Westcliff-on-Sea, Southchurch Road and London Road are where many of Southend's independent businesses now reside.[80] Hamlet Court Road was home to one of Southend's longest-standing business, Havens, which opened in 1901. In May 2017, the store announced they would be closing their store to concentrate as an online retailer.[81]

There are regular vintage fairs and markets in Southend, held at a variety of locations including the Leigh Community Centre and Garon Park.[82] A record fair is frequently held at West Leigh Schools in Leigh on Sea.[83]

Parks

Southend is home to many recreation grounds. Its first formal park to open was Prittlewell Square in the 19th century. Since then Priory Park and Victory Sports Grounds were donated by the town benefactor R A Jones, who also has the sports ground Jones Corner Recreation Ground named after his wife. Other formal parks that have opened since are Chalkwell Park and Southchurch Hall along with Southchurch Park, Garon Park and Gunners Park.

Southend Cliff Gardens

Southend Cliff Gardens Priory Park

Priory Park Prittlewell Square

Prittlewell Square

Conservation areas

Southend has various Conservation areas across the borough, with the first being designated in 1968.

Art, galleries, museums and libraries

Focal Point Gallery, based in The Forum, is South Essex's gallery for contemporary visual art, promoting and commissioning major solo exhibitions, group and thematic shows, a programme of events including performances, film screenings and talks, as well as offsite projects and temporary public artworks. The organisation is funded by Southend-on-Sea Borough Council and Arts Council England.[61]

Southend Museums Service, part of Southend on Sea City Council, operates a number of historic attractions, an art gallery and a museum in the city. These include: Beecroft Art Gallery, Southchurch Hall, Prittlewell Priory, Southend Pier Museum and the Central Museum on Victoria Avenue.[84] The Jazz Centre UK, a jazz cultural centre, has operated out of the Beecroft Art Gallery since 2017.[85][86]

The Old Waterworks Arts Center operates on North Road, Westcliff in the former Victorian water works building. It holds art exhibitions, talks and workshops.[87]

Metal, the art organisation set up by Jude Kelly OBE has been based in Chalkwell Hall since 2006.[88] The organisation offers residency space for artists and also organises the Village Green Art & Music Festival.[89] The park is also home to NetPark, which claims to be the world's first digital art park.[61]

Southend has several small libraries located in Leigh, Westcliff, Kent Elms and Southchurch. The central library has moved from its traditional location on Victoria Avenue to The Forum in Elmer Approach, a new facility paid for by Southend Council, South Essex College and The University of Essex. It replaced the former Farringdon Multistorey Car Park. The old Central Library building (built 1974) has become home to the Beecroft Gallery and the Jazz Centre UK.[61] This building had replaced the former Carnegie funded free library which is now home to the Southend Central Museum.

Southend Central Museum, Victoria Avenue

Southend Central Museum, Victoria Avenue Former home of Beecroft Art Gallery

Former home of Beecroft Art Gallery

Theatres

There are a number of theatres. The Edwardian Palace Theatre is a Grade II listed building dating from 1912. It shows plays by professional troupes and repertory groups, as well as comedy acts. The theatre has two circles and the steepest rake in Britain. Part of the theatre is a smaller venue called The Dixon Studio. The Cliffs Pavilion is a large building that hosts concerts and performances on ice, as well as pantomimes at Christmas opening in 1964. They are both owned by Southend Council and run by Southend Theatres Ltd.

The most recent closed theatre was the New Empire Theatre. It was, unlike the other two, privately owned. It was used more by amateur groups. The theatre was converted from the old ABC Cinema, which had been the Empire Theatre built in 1896. The New Empire Theatre closed in 2009 after a dispute between the trust that ran the theatre and its owners. The building was badly damaged by fire on Saturday 1 August 2015[90] and was demolished in 2017.[91]

The Clifftown Theatre is located in the former Clifftown United Reformed Church and as well as regular performances is part of the East 15 Acting School campus.[92]

The Cliffs Pavilion

The Cliffs Pavilion The former New Empire Theatre

The former New Empire Theatre Clifftown Theatre - part of East 15's Southend campus

Clifftown Theatre - part of East 15's Southend campus

Cinema

Southend has one cinema – the Odeon Multiplex at Victoria Circus which has eight screens. The borough of Southend had at one time a total of 18 cinema theatres,[93] with the most famous being the Odeon (formerly the Astoria Theatre), which as well as showing films hosted live entertainers including the Beatles and Laurel and Hardy.[94] This building no longer stands having been replaced by the Southend Campus of the University of Essex. There are plans to build a new 10 screen cinema and entertainment facility on the site of the Seaway Car Park.[95][96]

Southend has appeared in films over the years, with the New York New York arcade on Marine Parade being used in the British gangsta flick Essex Boys, the premiere of which took place at the Southend Odeon.[97] Southend Airport was used for the filming of the James Bond film Goldfinger.[98] Part of the 1989 black comedy film Killing Dad was set and filmed in Southend.[99]

Southend and the surrounding areas were heavily used and featured in the Viral Marketing[100] for the Universal Pictures 2022 American science fiction action film sequel Jurassic World Dominion, with a number of the featured videos on the DinoTracker website filmed in the Southend area[101] doubling for locations around the world. This is due to the fact that local resident and Jurassic World Franchise marketer Samuel Phillips utilised the area for both videos and imagery.[102]

The former ABC Cinema

The former ABC Cinema Former Astoria/Odeon cinema - High Street, Southend

Former Astoria/Odeon cinema - High Street, Southend The current Odeon

The current Odeon

Music

Southend has three major venues; Chinnerys, the Riga Club (formerly at the Cricketers Pub London Road) at The Dickens, and the Cliffs Pavilion.

Concerts are also shown at the Plaza, a Christian community centre and concert hall based on Southchurch Road,[103] which was formerly a cinema.[104]

Junk Club, at one time a centre of Southend's music scene, was predominantly held in the basement at the Royal Hotel during the period of 2001–06. Co-run by Oliver "Blitz" Abbott & Rhys Webb, of The Horrors, the underground club night played an eclectic mix from Post Punk to Acid House, 1960s Psychedelia to Electro. It was noted as spearheading what became known as the Southend Scene and was featured in the NME, Dazed & Confused, ID, Rolling Stone, Guardian and Vogue.[105] Acts associated with the scene included: The Horrors; These New Puritans; The Violets; Ipso Facto; Neils Children and The Errorplains.

There have also been a number of popular music videos filmed in Southend,[106] by such music artists as Oasis; Morrissey and George Michael.

Bands and musicians originating from Southend include Busted; Get Cape. Wear Cape. Fly; Danielle Dax; Eddie and the Hot Rods; Eight Rounds Rapid; The Horrors; The Kursaal Flyers; Nothing But Thieves; Procol Harum; Scroobius Pip; These New Puritans and Tonight.

Southend is mentioned in a number of songs including as the end destination in Billy Bragg's "A13, Trunk Road to the sea" where the final line of the chorus is "Southend's the end".[107]

Radio

In 1981, Southend became the home of Essex Radio, which broadcast from studios below Clifftown Road. The station was formed by several local companies, including Keddies, Garons & TOTS nightclub, with David Keddie, owner of the Keddies department store in Southend, becoming its chairman.[108] In 2004, the renamed Essex FM, then Heart Essex moved to studios in Chelmsford. It is now part of Heart East.

The BBC Local Radio station that broadcast to Southend is BBC Essex on 95.3 FM from the South Benfleet transmitter.[109]

On 28 March 2008, Southend got its own radio station for the first time which is also shared with Chelmsford Radio (formerly known as Dream 107.7 FM and Chelmer FM before that), Southend Radio started broadcasting on 105.1FM from purpose-built studios adjacent to the Adventure Island theme park.[110] The station merged with Chelmsford Radio in 2015 and became Radio Essex.

Television

Southend is served by London and East Anglia regional variations of the BBC and ITV. Television signals are received from either Crystal Palace or Sudbury TV transmitters.[111][112] The area can also pick up BBC South East and ITV Meridian from the Bluebell Hill TV transmitter.[113]

Southend has appeared in several television shows and advertisements.[114] It has been used on numerous occasions by the soap EastEnders with its most recent visit in 2022.[115][116] Southend Pier was used by ITV show Minder for its end credits in season 8, 9 and 10,[117] and since 2014 has been home to Jamie & Jimmy's Friday Night Feast. Advertisements have included Abbey National, CGU Pensions, National Lottery, the 2015 Vauxhall Corsa adverts featuring Electric Avenue, a seafront arcade[118] the 2018 Guide Dogs for the Blind campaign[119] and for the promo for David Hasselhoff's Dave programme Hoff the Record.[120]

In fiction

Southend is the seaside vacation place chosen by the John Knightley family in Emma by Jane Austen, published 1816.[121] The family arrived by stage coach, and strongly preferred it to the choice of the Perry family, Cromer, which was 100 miles from London, compared to the easier distance of 40 miles from the London home of the John and Isabella Knightley, as discussed at length with Mr. Woodhouse in the novel in Chapter XII of volume one.

In The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, after being saved from death in the vacuum of space, Arthur Dent and Ford Prefect find themselves in a distorted version of Southend (a consequence of the starship Heart of Gold's Infinite Improbability Drive). Dent briefly feared that both he and Prefect did in fact die, based on a childhood nightmare where his friends went to either Heaven or Hell but he went to Southend.

Dance on My Grave, a book by Aidan Chambers, is set in Southend.[122] Chambers had worked as a teacher in the city's Westcliff High School for Boys for three years.[123]

In the novel Starter for Ten by David Nicholls, the main character Brian Jackson comes from Southend-on-Sea.[124] The book was adapted into a 2006 film directed by Tom Vaughan.

Places of worship

There are churches in the borough catering to different Christian denominations, such as Our Lady Help of Christians and St Helen's Church for the Roman Catholic community. There are two synagogues; one for orthodox Jews, in Westcliff, and a reform synagogue in Chalkwell. Three mosques provide for the Muslim population; one run by the Bangladeshi community,[125] and the others run by the Pakistani community.[126][127] There are two Hindu Temples, BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir[128] and Southend Meenatshe Suntharasar Temple,[129] while there is one Buddhist temple, Amita Buddha Centre.[130]

York Road Market

Demolition of the historic covered market began on 23 April 2010.[131] The site became a car park. A temporary market was held there every Friday until 2012 after the closure of the former Southend market at the rear of the Odeon.[132] As of 2013, a market is now held in the High Street every Thursday with over 30 stalls.[133]

Twin town

Southend-on-Sea is twinned with:

Notable people

- David Amess (1952–2021), British politician and local MP who was stabbed to death in 2021; Southend was named a city in his honour.[135]

- Jasmine Armfield, actress[136]

- Trevor Bailey, cricketer[137]

- John Barber (1919–2004), former Finance Director of Ford of Europe & Managing Director of British Leyland.[138]

- Mathew Baynton, musician, writer, actor[139]

- David Bellos, professor/translator[140]

- Angie Best, ex-wife of George Best[141]

- Brinn Bevan, artistic gymnast[142]

- James Booth, actor[143]

- James Bourne, musician, singer Busted[144]

- Tim Bowler, children's author[145]

- Kevin Bowyer, concert organist[146]

- Gary Brooker, lead singer of Procol Harum[147]

- Dave Brown, comedian and actor[148]

- Cameron Carter-Vickers, American soccer player[149]

- Dean Chalkley, photographer[150]

- Aidan Chambers, Author[123]

- Jeannie Clark, former professional wrestling manager[151]

- Brian Cleeve, author and broadcaster[152]

- Dick Clement, screenwriter[153]

- Dorothy Coke, artist[154]

- Eric Kirkham Cole, businessman[155]

- Peter Cook, architect[156]

- Phil Cornwell, actor and impressionist[157]

- Tina Cousins, singer[158]

- Gemma Craven, actress[159]

- Rosalie Cunningham, singer-songwriter-multi-instrumentalist[160]

- Matthew Cutler, ballroom dancer[161]

- Danielle Dax, musician, actress and performance artist[162]

- Warwick Deeping, author[163]

- Richard de Southchurch, knight and landowner.[164]

- Andy Ducat, cricketer, footballer.[165]

- Sam Duckworth, musician[166]

- Warren Ellis, novelist and comic writer[167]

- Nathalie Emmanuel, actress[168]

- Digby Fairweather, jazz musician, author, founder of the National Jazz Archive.[169]

- Mark Foster, swimmer[170]

- John Fowles, author[171]

- Becky Frater, first female helicopter commander in the Royal Navy and female member of the Black Cats display team[172]

- John Georgiadis, violinist and conductor[173]

- Edward Greenfield (3 July 1928 – 1 July 2015) chief music writer in The Guardian from 1977 to 1993 and biographer of Andre Previn[174]

- Benjamin Grosvenor, pianist[175]

- Daniel Hardcastle, author[176]

- Roy Hay, musician[177]

- Joshua Hayward, guitarist for The Horrors[178]

- John Hodge, aerospace engineer[179]

- John Horsley, actor[180]

- John Hutton, politician[181]

- Dominic Iorfa , football player[182]

- Wilko Johnson, singer, guitarist and songwriter; Game of Thrones actor[183]

- Daniel Jones, musician, producer[184]

- R. A. Jones, store owner and town benefactor[185]

- Phill Jupitus, comedian[186]

- Mickey Jupp, musician[187]

- Russell Kane, comedian[188]

- Dominic Littlewood, TV presenter[189]

- David Lloyd, tennis player[190]

- John Lloyd, tennis player[190]

- Robert Lloyd, opera singer[191]

- Ron Martin, Southend United chairman, 1998–present[192]

- Frank Matcham, English theatre designer, retired and died in Southend[193][194]

- Lee Mead, musical theatre actor[195]

- Jon Miller, TV presenter[196]

- Helen Mirren, actress[197]

- Jack Monroe, blogger, campaigner[198]

- Peggy Mount, actress[199]

- Tris Vonna Michell, artist[200]

- Maajid Nawaz, former Islamist activist who now campaigns against extremism[201]

- Julian Okai, English footballer[202]

- Michael Osborne, first-class cricketer[203]

- Annabel Port, broadcaster[204]

- Stephen Port, serial killer[205]

- Spencer Prior, footballer[206]

- Lara Pulver, actress[207]

- Rachel Riley, Countdown co-presenter[208]

- Simon Schama, historian / TV presenter[209]

- Anne Stallybrass, actress[210]

- Vivian Stanshall, musician[211]

- Sam Strike, actor[212]

- Keith Taylor, politician[213]

- Peter Taylor, footballer and football manager[214]

- Theoretical Girl, singer-songwriter[215]

- Steve Tilson, footballer – voted Southend United's greatest ever player[216]

- Kara Tointon, actress[217]

- Hannah Tointon, actress[217]

- Robin Trower, rock-blues guitarist[218]

- Gary Vandermolen, footballer[219]

- David Webb, football manager[220]

- Paul Webb, musician, bassist for Talk Talk[221]

- Rhys "Spider" Webb, bassist of The Horrors[178]

- Michael Wilding, actor[222]

- David Witts, actor[223]

- C. R. Alder Wright (1844–1894), scientist - founder of the Royal Institute of Chemistry and inventor of Heroin[224]

- Ian Yearsley, local historian and author[225]

- Nothing But Thieves, musicians[226]

Freedom of the City

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Southend-on-Sea.

Individuals

- David Stanley BEM: 24 July 2023.[227]

- Kevin Maher: March 2024.[228]

Military Units

- 1st Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment: 17 June 2010.[229]

References

- ↑ "Local statistics – Office for National Statistics". www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- 1 2 Else, David, ed. (2009). England. Lonely Planet travel guide (5th ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-74104-590-1.

- 1 2 "Sir David Amess: Southend to become a city in honour of MP". BBC News. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ "Southend to become city in honour of Sir David Amess". The Guardian. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Southend: Prince Charles presents city status document". BBC News. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ↑ "Warrant to prepare Letters Patent for conferring city status on Southend-on-Sea". Crown Office. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Southend". Naval & Military Club, Southend-on-Sea. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "History – About Us – Clifftown Studios & Theatre". Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ "Fire burns through Southend Pier". CBBC Newsround. 10 October 2005. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ↑ "skills education careers – South Essex College". www.southessex.ac.uk.

- ↑ "southendairshow.com". Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "Southend-on-Sea's City Status". Southend-On-Sea Borough Council. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ Emes, Toby (22 September 2021). "Bid to make Southend a city officially launched". Basildon Canvey Southend Echo.

- ↑ "Southend City". southend.city. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ↑ "Pictures: 'Emotional' concert held at the Cliffs in honour of Sir David Amess". Echo. 14 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- 1 2 "What you need to know about week long celebrations to mark Southend city status". Echo. 7 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ↑ "Stars of Amess memorial concert: "we're going to do a lot in the city in Sir David's name"". Greatest Hits Radio (Essex). Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ↑ Gray, Brad (23 January 2020). "Why Essex could have a second city in 2021". EssexLive.

- ↑ "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ "Southend on Sea Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ↑ "Southend". Chelmsford Chronicle. 31 August 1866. p. 5. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ↑ Yearsley, Ian (2016). Southend in 50 buildings. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-5189-7. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ↑ "Local Government Board's Provisional Orders Confirmation (No. 7) Act 1897". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ Bettley, James (2007). Pevsner, Nikolaus (ed.). Essex. Pevsner Architectural Guides: The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. pp. 690–691. ISBN 978-0-300-11614-4.

- ↑ "Sopot – Southend's Twin Town". Southend-on-Sea Borough Council. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ "Southend Civic Centre". Modern Mooch. 14 June 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Ramesh, Randeep (23 February 2011). "The child poverty map of Britain". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Rogers, Simon (31 March 2011). "Deprivation mapped: how you show the poorest (and richest) places in England". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "2011 Census – Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ "2011 Census – Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ↑ Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

- ↑ includes hunting and forestry

- ↑ includes energy and construction

- ↑ includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

- ↑ "300 new jobs for Southend". Echo. 31 May 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ↑ "More than 100 Insure & Go employees face redundancy in Southend – Evening Echo p.16 Nov 2016". 16 November 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "Centrica – Our Facilities". Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Ventrica, Southend, set to offer 200 new jobs – Evening Echo Cornell.A p.13 August 2018". 13 August 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "HSBC cuts 1700 jobs". The Guardian. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ Swinney, Paul (15 February 2016). "Southend is Britain's only high-wage, high-welfare city. What gives?". City Metric. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ CEGB Statistical Yearbook 1965, 1966. CEGB, London.

- ↑ "Eastern National – southendtimeline". Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "The closure of Arriva Southend's London Road Garage – 2000 By Richard Delahoy". Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "End of the road for busman Denis – Evening Echo p.19 February 2009". 19 February 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ↑ John Robert Day, John Reed (2005). The story of London's underground (9 ed.). Capital Transport. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-85414-289-4.

- ↑ "Southend Cliff Railway". The Heritage Trail. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Southend-on-Sea climate averages". Met Office. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ "Shoeburyness Climatic Averages 1991–2020". Met Office. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ "East 15 Acting School". Clifftown Theatre. 23 January 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "South Essex College Merger Approved". 30 November 2009.

- ↑ "Southend on Sea Athletic Club | Founded 1905". www.southend-on-sea-athletic-club.co.uk.

- ↑ "Leisure Centres Directory - Southend Swimming & Diving Centre at Southend Leisure & Tennis Centre | Southend-on-Sea Borough Council". Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ "History of Southend Pier". Southend-on-Sea Borough Council. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ↑ "Southend – Carnival Archive". Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Southend Carnival week starts Friday – Evening Echo Buckley.K p.8 August 2018". 8 August 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Historic cliff lift reopens following refurbishment". BBC Essex. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "South Eastern Vintage and Classic Vehicle Club". Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "Bikers ride into town for Southend Shakedown". Echo. 26 April 2011.

- ↑ "Latest News". Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "An arty weekend in … Southend-on-Sea, Essex". The Guardian. 22 March 2023.

- ↑ "LuminoCity Southend: a look back after festival cancelled". Evening Echo. 6 January 2024.

- ↑ "Old Leigh Regatta". Leigh Lions. 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Leigh Folk Festival: organisers cancel 2024 event". Evening Echo. 28 November 2023.

- ↑ "Southend Jazz Festival returning for a fourth year". Evening Echo. 6 September 2023.

- ↑ "Village Green festival keeps entry charge as details for 2015 bash are revealed". Evening Echo. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "Victoria Shopping Centre – Southend Timeline". Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "The Royals Shopping Centre". Southend Timeline. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ↑ "Shopping in Southend-on-Sea – Sarfend.co.uk". Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Garons Cinema – cinematreasures.org". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Edinburgh Gazette 11 April 1967" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Owen Wallis & Sons, Southend – Flickr". 14 January 2004. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Old Shop Fronts & Names – Sarfend.co.uk". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Essex". The British Journalof Photography. 132: 257. 1985.

- ↑ "Acquisition of small food chains – Schofield and Martin". waitrosememorystore.org.uk.

- ↑ "Southend's oldest department store to shut after 120 years". Evening Echo. 23 June 2017.

- ↑ "About Us". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Fifth generation of family joins Ravens – Evening Echo p.3 Sept 2010". 3 September 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "Southend's oldest department store to shut after 120 years – Evening Echo p.22 June 2017". 23 June 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Visit Southend – A Shopper's paradise". Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "End of an era as Havens store prepares to close after almost 100 years on the high street – Evening Echo p.12 May 2017". 12 May 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "The Big Southend Vintage & Retro Fair". Visit Southend. 19 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Record Fairs UK". Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Southend Museums". Southend Museums Service. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Southend-on-Sea: Jazz Centre set to remain in Beecroft Gallery home". BBC. 31 May 2023.

- ↑ "The Jazz Centre UK wins fight to stay at Beecroft Art Gallery location". JazzWise. 14 July 2023.

- ↑ "Westcliff TAP gallery opens after fire". Southend Standard. 17 January 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "Metal – visitsouthend.co.uk". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "Southend-on-Sea: the arty way is Essex – The Guardian – Joanna O'Connor p.23 July 2017". TheGuardian.com. 23 July 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "Fall of the Empire – burned out theatre in ictures". Evening Echo. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "Cinema demolition is finally underway". Southend Standard. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ↑ "Clifftown Theatre". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ "Southend Timeline". Southend Timeline.

- ↑ "Start The Revolution Without Me: More Memories of Southend Cinema!". 23 August 2010.

- ↑ "Ne Ten Screen Cinema Planned for Southend". Evening Echo. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ "REVEALED First Look at What £50 Million Southend Fun Palace Looks Like – Southend Standard". 6 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ "Essex Boys premiere saw A-listers head to Southend's Odeon". Echo. 11 October 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ↑ "Look back on the day Sir Sean Connery flew into Southend for Bond filming". Echo. 4 November 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ↑ "Killing Dad". Time Out Worldwide. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ↑ "Jurassic World Dominion Dinotracker". www.dinotracker.com. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ England, Sophie (25 June 2022). "Jurassic World marketing campaigns filmed in Southend". Echo News. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ↑ "Jurassic World marketing campaigns filmed in Southend". Echo Essex. 25 June 2022. p. 1. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ↑ "Concert Series – Southend Borough Council". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Plaza Centre – Southend Christian Fellowship". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ↑ "The beach boys". The Guardian. 1 September 2006.

- ↑ "Music Videos Shot in Southend", Love Southend

- ↑ "Billy Bragg - A13 Trunk Road to the Sea Lyrics". SongMeanings. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ↑ "Keddies". In and Around Southend-on-Sea. Sarfend.co.uk. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mb21 - Transmitter Information - BBC Essex".

- ↑ "Sarfend.co.uk's page on Radio in Southend". Archived from the original on 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "Crystal Palace (Greater London, England) Full Freeview transmitter". May 2004.

- ↑ "Sudbury (Suffolk, England) Full Freeview transmitter". May 2004.

- ↑ "Bluebell Hill (Medway, England) Full Freeview transmitter". May 2004.

- ↑ "Southend Timeline – TV Stars". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "EastEnders starts take to Southend Streets". Evening Echo. 3 October 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "EastEnders: Times they have filmed in the city of Southend". Evening Echo. 26 March 2022.

- ↑ "Minder titles & Credits". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Southend is backfrop for new prime time ad". Evening Echo. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Guide Dogs' new DRTV ad reveals inspirational ambitions of a tattoo artist following sight loss". Marketing Communication News. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "Hoff The Record – Dave Channel – UKTV.co.uk". Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "South End, Essex – Jane Austen Gazetteer – pemberley.com". Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Summer of 85". filmuforia.co.uk. 17 October 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- 1 2 "Adrian Chambers". British Council.org. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ "Geek is the word". The Guardian. 12 October 2003.

- ↑ "Google Mosque Map – UK Mosques Directory". mosques.muslimsinbritain.org. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Google Mosque Map – UK Mosques Directory". mosques.muslimsinbritain.org. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Google Mosque Map – UK Mosques Directory". mosques.muslimsinbritain.org. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir". BAPS Charities. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ "Southend Meenatshe Suntharasar Temple". Facebook. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ "Mayor to open town's first Buddhist temple". Evening Echo. 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Southend York Road Market". Sarfend.co.uk. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ "Workmen move in to demolish market". Echo. 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Southend market to double in size". Echo. 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Holmes, Katherine. "Town Twinning". www.southend.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ Webber, Esther (15 October 2021). "UK MP David Amess dies after stabbing attack". Politico. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ "Jasmine Armfield Age and Career including Eastenders role as Bex Fowler – Metro.co.uk". 28 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Former England cricketer Trevor Bailey's death in fire 'accidental' – bbc.co.uk". BBC News. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Obituary – John Barber". aronline.co.uk. 13 November 2004. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "MATHEW BAYNTON On Good and Bad Comedy – The Protagonist Magazine". Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Language expert Bellos explores the art and science of translation". Princeton University.

- ↑ "The next Best thing". Independent.ie. 7 June 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ↑ "Brinn Bevan profile". TeamGB.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ The Hadleigh and Thundersley Community Archive Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ "Busted to return for a reunion tour with Southend Singer James Bourne – Southend Standard". 10 December 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "ACHUKA – Children's Books UK – Tim Bowler". www.achuka.co.uk.

- ↑ "Kevin Bowyer profile – sound Scotland.co.uk". Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Johansen, Claes (2000). Procol Harum: Beyond the Pale. SAF Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-946-71928-0.

- ↑ "Behind the boosh photographs by Dave Brown - wsimag.com". 13 October 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "USA defender Cameron Carter-Vickers first spotted in Leigh". 23 November 2022.

- ↑ "Dean Chalkley – The Trawler". 28 November 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "P1: Jeanie Clarke/Lady Blossom pens 'Through the Shattered Glass'- Miami Herald". Miami Herald. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Burke, Sir Bernard, Burke's Irish family records, Burke's Peerage, 1976

- ↑ "Homage to Clement and La Frenais the writing duo who transformed British comedy – The Spectator". 26 September 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Penny Dunford (1990). A Biographical Dictionary of Women Artists in Europe and America since 1850. Harvester Wheatsheaf. ISBN 0-7108-1144-6.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Cole, Eric Kirkham by Rowland F. Pocock

- ↑ "The Knighthood of Professor Peter Cook". University College London. 22 June 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "Portrait of a Driver Phil Cornwell – The Telegraph". 20 November 2004. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Southend Tina gets the home town nerves – The Daily Gazette". 13 July 1999. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Southend Gemma of a daughter – The Daily Gazette". 10 April 2000. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Glass, Polly (20 September 2019). "Rosalie Cunningham". Prog.

- ↑ "Strictly Dancing Essex Feature – bbc.co.uk". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Colin Larkin, ed. (2003). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Eighties Music (Third ed.). Virgin Books. p. 144/5. ISBN 1-85227-969-9.

- ↑ Grover, Mary (2009). The Ordeal of Warwick Deeping: Middlebrow Authorship and Cultural Embarrassment. Associated University Presse. ISBN 978-0-8386-4188-0. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Public Record Office (1912). Inquisitions Post Mortem, vol. III, Edward I. London. pp. 109–10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "The remarkable story of Southend's sport star Andy Ducat". Evening Echo. 14 March 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Duckworth interview: 'I love making music and without sounding corny it feels like this is what I'm meant to do'". The Independent. 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ "Warren Ellis: On cannibalism – wired.co.uk". Wired UK. 5 July 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Celeb Birthdays for the Week of March 1–7". The New York Times. 26 February 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Digby Fairweather marks the 20th anniversary of his band the Half Dozen". Daily Gazette. 27 September 2015.

- ↑ Lamont, Tom (1 February 2009). "Local heroes: Mark Foster". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "BBC interview with John Fowles from October 1977". 4 October 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Southend Air Festival May 2010". UK Airshow Review. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ "John Georgiadis, former LSO leader, dies aged 81". Classical Music.

- ↑ "Edward Greenfield Writer Obituary". The Telegraph. 3 July 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "Anthem 2012 – Metal culture.co.uk". Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "NERD CUBED Limited – Companies House". Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Roy Hay – culture club.co.uk". Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- 1 2 "The Horrors' Joshua Hayward on new album V". The Skinny. 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "NASA pays tribute to Leigh's John Hodge". Evening Echo. 1 June 2021.

- ↑ "Obituary – John Horsley, actor". The Scotsman. 16 January 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ Richard Northedge "Hutton dressed as lamb?", The Daily Telegraph, 22 July 2007

- ↑ "Southend born Dominic Iorfa trains with full England squad". Evening Echo. 3 September 2015.

- ↑ "Wilko Johnson backs campaign to save Southend music venue". bbc.co.uk. 19 February 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ "Daniel Jones Fanclub". facebook. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ "Bring Southend's R A Jones clock back to life". Echo. 17 March 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ "Phill Jupitus you ask the questions". The Independent. 13 March 2003. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ "I needed to chronicle the truth about a Southend rock legend Mickey Jupp". Evening Echo. 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Comedian to tie the knot in Southchurch Hall ceremony". Evening Echo. 6 January 2010.

- ↑ "Dom Littlewood: I'm still a Southend boy". Evening Echo. 8 August 2008.

- 1 2 "The Murray brothers go one step further than Southend's Lloyd brothers and win the Davis Cup". The Argus. 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Adam, Nicky, ed. (1993). Who's Who in British Opera. Aldershot: Scholar Press. ISBN 0-85967-894-6.

- ↑ Tallentire, Mark (22 August 2010). "Southend's new manager fighting against tide to keep Shrimpers afloat". Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Frank Matcham". Manchester Victorian Architects. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ Pevsner. N (2007). Essex: The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. p. 716. ISBN 978-0-300-11614-4.

- ↑ "Relative Values: Lee Mead and his mother, Jo". The Times. 18 November 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ "Jon Miller: Boffin presenter of 'How'". Independent. 7 August 2008.

- ↑ Mirren, Helen (25 March 2008). In the Frame: My Life in Words and Pictures. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-41656-760-8.

- ↑ Monroe, Jack (7 May 2014). "About Jack". Cooking on a Bootstrap. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Hayward, Anthony. "Obituary – Peggy Mount", The Independent, 14 November 2001, p. 6

- ↑ "Tris Vonna-Michell". Tate. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ Shariatmadari, David. "Maajid Nawaz: how a former Islamist became David Cameron's anti-extremism adviser". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ↑ "Julian Okai".

- ↑ "Michael Osborne". Wisden. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ "Mirror Works: Port with stilts on; HOW ANNABEL BECAME A RADIO STUNT QUEEN". The Mirror. 20 November 2003.

- ↑ De Simone, Daniel (24 November 2016). "How did police miss Barking serial killer Stephen Port?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Prior is the new coach for womens national soccer team". Papau New Guinea Post Courier. 23 November 2022.

- ↑ "Lara Pulver". London Theatre. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ "More Success for Rachel Riley". Thorpe Hall School. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ↑ "Simon Schama Interview | The Jewish Chronicle". Thejc.com. 12 October 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Anne Stallybrass obituary". The Times. 4 August 2021. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ↑ Vivian Stanshall: Essex Teenager to Renaissance Man (1994), BBC Radio 4

- ↑ "Southend teen to star in TV spy show". Evening Echo. 13 December 2012.

- ↑ "Keith Taylor obituary". Green World. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ Mike Purkiss & Nigel Sands (1990). Crystal Palace: A Complete Record 1905–1989. Breedon Books. p. 89. ISBN 0-907969-54-2.

- ↑ "Good music, not fame, drives me". Evening Echo. 29 July 2009.

- ↑ "#FL125: Tilson a Southend great – southendunited.co.uk". Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- 1 2 "Dad's pride in his two TV star daughters". Echo-news.co.uk. 11 October 2010.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. pp. 1192/3. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- ↑ Jeremy Last (21 March 2008). "Interview: The Englishman who won over Jerusalem". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ↑ "Catching up with former Southend United and Torquay Manager David Webb". Evening Echo. 16 September 2019.

- ↑ "Classic Album: Talk Talk The Colour of Spring". Classic Pop. 25 February 2021.

- ↑ Flint, Peter (9 July 1979). "Michael Wilding, British Movie Star". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ Thomas, Emma (27 January 2013). "Eastenders star David Witts thanks former Southend High School for Boys teacher". Echo. Newsquest. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Royal Society".

- ↑ "Ingatestone & Fryerning: A History" by Ian Yearsley, p.1

- ↑ Buckley, Kelly (17 July 2014). "We've just been signed to the same record label as Pharrell Williams and David Bowie". echo-news.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ Peter Walker and Christine Sexton (24 July 2023). "Founder of Southend's Music Man Project given freedom of city". BBC News Essex. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ Sexton, Christine (16 December 2023). "Blues boss to receive Freedom of the City accolade". BBC News Essex. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ↑ "Royal Anglians given freedom of Southend". BBC News Essex. 17 June 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2023.