| Sonnet 7 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

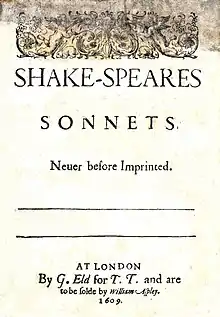

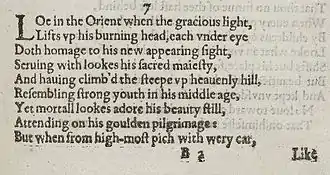

The first nine lines of Sonnet 7 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 7 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

Structure

Sonnet 7 is a typical English or Shakespearean sonnet. This type of sonnet consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet, and follows the form's rhyme scheme: abab cdcd efef gg. The sonnet is written in iambic pentameter, a type of metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions per line, as exemplified in line five (where "heavenly" is contracted to two syllables):

× / × / × / × / × / And having climbed the steep-up heavenly hill, (7.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The next line presents a somewhat unusual metrical problem. It can be scanned regularly:

× / × / × / × / × / Resembling strong youth in his middle age, (7.6)

The problem arises with the words "strong youth". Both words have tonic stress, but that of "strong" is normally subordinated to that of "youth", allowing them comfortably to fill × / positions, not / ×. The scansion above would seem to suggest a contrastive accent placed upon "strong", which may not be appropriate as the more salient contrast is between youth and age. Probably the line should be scanned:

× / × / / × × / × / Resembling strong youth in his middle age, (7.6)

A reversal of the third ictus (as shown above) is normally preceded by at least a slight intonational break, which "strong youth" does not allow. Peter Groves calls this a "harsh mapping", and recommends that in performance "the best thing to do is to prolong the subordinated S-syllable [here, "strong"] ... the effect of this is to throw a degree of emphasis on it".[2]

Interpretive synopsis

Each day for the sun is like one lifetime for man. He is youthful, capable, and admired in the early stages of his lifetime, much like the sun is admired in the early day. But as the sun sets and a man's aging gets the best of him, he is facing frailty and mortality, and those once concerned with man and sun are now inattentive. At night the sun is forgotten. At death man is forgotten, unless he leaves a legacy in the form of a human son.

Commentary

This sonnet introduces new imagery, comparing the Youth to a morning sun, looked up to by lesser beings. But as he grows older he will be increasingly ignored unless he has a son to carry forward his identity into the next generation. The poem draws on classical imagery, common in art of the period, in which Helios or Apollo cross the sky in his chariot - an emblem of passing time. The word "car" was also used classically of the sun's chariot (compare R3. 5.3.20-1, "The weary Sunne, hath made a Golden set, / And by the bright Tract of his fiery Carre").

Textual analysis

Not unlike other Shakespearean sonnets, sonnet 7 utilizes simplistic "word play" and "key words" to underline the thematic meaning. These words appear in root form or similar variations.[3] The poetic eye finds interest in the use of 'looks' (line 4), 'looks' (line 7), 'look' (line 12), and 'unlook'd' (line 14). A more thematic word play used is those words denoting 'age', but that are not explicitly identifiable.

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

...

Attending on his golden pilgrimage; (7.3-6)

By using words typical of expressing human features (e.g. youth), the reader begins to identify the sun as being representative of man. The sun does not assume an actual 'age', therefore we infer that the subject of the poem is man.

Critics in dialogue

Burden of beauty

Although Robin Hackett makes a considerably in-depth argument that Shakespeare's Sonnet 7 may be read in context with Virginia Woolf's The Waves as the story of an imperialistic "sun hero",[4] the potential bending of Shakespeare's work this analysis threatens may be best illustrated by the substantial lack of any other criticism seeking the same claim. Like Woolf, Hackett ventures that Shakespeare creates a poem "in which all characters and events revolve around a larger-than-life hero, whose rise or fall, or rise and fall, determines the plot of the story".[5] As Michael Shoenfeldt points out, however, in "The Sonnets," the contextual placement of Sonnet 7, being among the first 126 that address the young man, gives the sonnet a substantially different reading: "the conventional praise of chaste beauty, and turn[s] it on its head — the young man's beauty burdens him with the responsibility to reproduce, a responsibility he is currently shirking".[6] The heir, referred to as "son" in Sonnet 7, is to "continue his beauty beyond the inexorable decay of aging".[7] Decay of honor and beauty, often referred to in the sonnets addressed to the young man, are here explicitly paralleled with the sun's passage through the sky. As each day the sun rises and falls, so the young man will rise and fall both in beauty and admiration. The only way to "continue his beauty" is to reproduce. However uncommon direct reference to decay is in Sonnet 7, Thomas Tyler in Shakespeare's Sonnets ensures the use of verbs like "reeleth" indirectly evoke an image of decay by fatigue. "Reeleth" according to Tyler means "worn out by fatigue".[8]

Profound use of pronoun

Shoenfeldt further addresses the abundance of sexual tension surrounding the issue of reproduction in Sonnet 7. Many as "fact" held the medical belief that each orgasm reduced one's life by a certain unit. Shakespeare may be struggling with this troubling "fact" in the image of the falling sun "from highmost pitch".[9] Penelope Freedman accounts for this tension in the grammatical usage of "you" and "thou" in Power and Passion in Shakespeare's Pronouns: "Linguists have long since identified one isolated feature of verbal exchange in early modern English that can serve as an index to social relationships. It is generally accepted that the selection of 'thou' or 'you,' the pronouns of address, can register relations of power and solidarity".[10] The singular use of "thou", which Freedman notes had a "dual role" to mark the emotions of anger and intimacy[11] solely in the couplet of Sonnet 7 carefully mimics the height of tension in the sonnet, bringing it to a close with a mark of intimacy, and perhaps contempt, at the refusal of the addressee to reproduce. Whether this intimacy is based on a lovers' relationship is difficult to accurately assess. Freeman comments how there is evidence of "thou" being used between family members but hardly any between lovers.[12] Instead, what can be inferred is that the two characters in Sonnet 7 are intimate enough to be of the same social class and to make a "direct appeal" of one another.[13] The linguistic strength of a direct appeal of the couplet opposes the image of frailty in the third quatrain. Giving the hope of an escape from decay, the couplet restores what seems to be lost in the third quatrain.

Imperialism

Reverting to Hackett's criticism, Sonnet 7 may indeed be "read as a story of imperialism".[14] By noting Shakespeare's use of the word "orient" in the first line of the sonnet, Hackett begins his exegesis. The Orient was a common link, at least as far as quintessential British narratives go, to the idea of wealth and prosperity. Hackett also connects the use of "golden pilgrimage" as more evidence of wealth seeking by way of imperialism. The "burning head" is that of an imperialistic ruler; "new-appearing sight" is this civilized knowledge given to the colonized. This type of reading allows "serving with looks" to be less metaphorical and more practical, alluding to the newly colonized people's duty to pay homage to the new ruler. With this reading, the sonnet may be looked at as a warning to rulers to remain powerful, lest people "look another way" and follow a new imperialistic ruler.[15] "The sonnet with its metaphor of the rise and fall of the sun, . . . can be read as an illustration of not only the fate of an adored man who fails to beget a son, but also the fate of a colonizing power that fails to produce either her heroes (and their military strength) or the ideology that sends those heroes to seek fortunes on the boundaries of empire".[16]

Cosmic economy

Thomas Greene believes the first clauses of early Shakespearean sonnets are haunted by 'cosmic' or 'existential' economics. The second clause issues hope for stability of beauty and immortality. This idea is rather modern and equates human value with economics.[17] The sun in sonnet 7 is an imperialistic empire that controls the economy of the world. The economic status of its governed is completely dependent upon the sun's immortality. If the sun did not rise, there would be no harvest and no profit. The implied man in sonnet 7 also has an economic function in his humanity. He is a cog in the machine of imperialism. A constituent of his governing body politic as well as to the greatest ruler – the sun. His complete reliance on the sun for economic gain is slave-like. Man waits for the sun to rise in the morning, labors under its heat, then feebly ends his days work, ever closer to his mortality. This sonnet is epideictic rhetoric of both blame and praise: blaming the sun for reminding man of his immortality, and praising the sun for the vast pleasures it brings man in his short lifetime. What are most highly valued of all are those that transcend time, and that is the sun.[18]

Metaphysics

The relationship between man and sun in sonnet 7 is metaphysical. The sun is the center of our being, but is also an object of desire. We want the sun's immortality. But man and the sun rely on one another to coexist. Man needs sun to survive on earth, and the sun would be of no significance without man. Man will cycle ad nauseam in this world yet the sun stays the same. The sun is reliable and unchanging. To the sun, one man is the same to another is the same to another.

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ Groves 2013, pp 42-43.

- ↑ Vendler 1997, p 75.

- ↑ Hackett 1999, p 263.

- ↑ Hackett 1999, p 269.

- ↑ Schoenfeldt 2007, p 128.

- ↑ Schoenfeldt 2007, p 128.

- ↑ Tyler 1890.

- ↑ Schoenfeldt 2007, p 132.

- ↑ Freedman 2007, p 3.

- ↑ Freedman 2007, p 5.

- ↑ Freedman 2007, p 16.

- ↑ Freedman 2007, p 17.

- ↑ Hackett 1999, p 263.

- ↑ Hackett 1999, p 263-64.

- ↑ Hackett 1999, p 264.

- ↑ Engle 1989, p 832.

- ↑ Engle 1989, p 834.

References

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Engle, Lars (October 1989). Afloat in Thick Deeps: Shakespeare's Sonnets on Certainty. PMLA 104. pp. 832–843.

- Freedman, Penelope (2007). Power and Passion in Shakespeare's Pronouns. Hampshire: Asgate. pp. 3, 5. 16–17.

- Groves, Peter (2013), Rhythm and Meaning in Shakespeare: A Guide for Readers and Actors, Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, ISBN 978-1-921867-81-1

- Hackett, Robin (1999). Supplanting Shakespeare’s Rising Sons: A Perverse Reading Through Woolf's The Waves: Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature. 18. pp. 263–280.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Larsen, Kenneth J. Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. http://www.williamshakespeare-sonnets.com

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. pp. 128, 132.

- Tyler, Thomas (1990). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London D. Nutt.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 7 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 7 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase of sonnet in modern language

- Analysis of the sonnet

.png.webp)