Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Unskilled or low-skill slaves labored in the fields, mines, and mills with few opportunities for advancement and little chance of freedom. Skilled and educated slaves—including artisans, chefs, domestic staff and personal attendants, entertainers, business managers, accountants and bankers, educators at all levels, secretaries and librarians, civil servants, and physicians—occupied a more privileged tier of servitude and could hope to obtain freedom through one of several well-defined paths with protections under the law. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a distinguishing feature of Rome's system of slavery, resulting in a significant and influential number of freedpersons in Roman society.

At all levels of employment, free working people, former slaves, and the enslaved mostly did the same kinds of jobs. Elite Romans whose wealth came from property ownership saw little difference between slavery and a dependence on earning wages from labor. Slaves were themselves considered property under Roman law and had no rights of legal personhood. Unlike Roman citizens, by law they could be subjected to corporal punishment, sexual exploitation, torture, and summary execution. The most brutal forms of punishment were reserved for slaves. The adequacy of their diet, shelter, clothing, and healthcare was dependent on their perceived utility to owners whose impulses might be cruel or situationally humane.

Some people were born into slavery as the child of an enslaved mother. Others became slaves. War captives were considered legally enslaved, and Roman military expansion during the Republican era was a major source of slaves. From the 2nd century BC through late antiquity, kidnapping and piracy put freeborn people all around the Mediterranean at risk of illegal enslavement, to which the children of poor families were especially vulnerable. Although a law was passed to ban debt slavery quite early in Rome's history, some people sold themselves into contractual slavery to escape poverty. The slave trade, lightly taxed and regulated, flourished in all reaches of the Roman Empire and across borders.

In antiquity, slavery was seen as the political consequence of one group dominating another, and people of any race, ethnicity, or place of origin might become slaves, including freeborn Romans. Slavery was practiced within all communities of the Roman Empire, including among Jews and Christians. Even modest households might expect to have two or three slaves.

A period of slave rebellions ended with the defeat of Spartacus in 71 BC; slave uprisings grew rare in the Imperial era, when individual escape was a more persistent form of resistance. Fugitive slave-hunting was the most concerted form of policing in the Roman Empire.

Moral discourse on slavery was concerned with the treatment of slaves, and abolitionist views were almost nonexistent. Inscriptions set up by slaves and freedpersons and the art and decoration of their houses offer glimpses of how they saw themselves. A few writers and philosophers of the Roman era were former slaves or the sons of freed slaves. Some scholars have made efforts to imagine more deeply the lived experiences of slaves in the Roman world through comparisons to the Atlantic slave trade, but no portrait of the "typical" Roman slave emerges from the wide range of work performed by slaves and freedmen and the complex distinctions among their social and legal statuses.

Origins

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

From Rome's earliest historical period, domestic slaves were part of a familia, the body of a household's dependents—a word especially, or sometimes limited to, referring to the slaves collectively.[3] Pliny (1st century AD) was nostalgic for a time when "the ancients" lived more intimately in a household with no need for "legions of slaves"—but still imagined this simpler domestic life as supported by the possession of a slave.[4]

All those belonging to the familia were subject to the paterfamilias, the "father" or head of household and more precisely the estate owner. According to Seneca, the early Romans coined paterfamilias as a euphemism for the relationship of a master to his slaves.[5] The word for "master" was dominus as the one who controlled the domain of the domus (household);[6] dominium was the word for his control over the slaves.[7] The paterfamilias held the power of life and death (vitae necisque potestas) over the dependents of his household,[8] including his sons and daughters as well as slaves.[9] The Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1st century AD) asserts that this right dated back to the legendary time of Romulus.[10]

In contrast to Greek city-states, Rome was an ethnically diverse population and incorporated former slaves as citizens. Dionysius found it remarkable that when Romans manumitted their slaves, they gave them Roman citizenship as well.[11] Myths of Rome's founding sought to account for both this heterogeneity[12] and the role of freedmen in Roman society.[13] The legendary founding by Romulus began with his establishment of a place of refuge that, according to the Augustan-era historian Livy, attracted "mostly former slaves, vagabonds, and runaways all looking for a fresh start" as citizens of the new city, which Livy considers a source of Rome's strength.[14] Servius Tullius, the semi-legendary sixth king of Rome, was said to have been the son of a slave woman,[15] and the cultural role of slavery is embedded in some religious festivals and temples that the Romans associated with his reign.

Some legal and religious developments pertaining to slavery thus can be discerned even in Rome's earliest institutions. The Twelve Tables, the earliest Roman legal code, dated traditionally to 451/450 BC, do not contain law defining slavery, the existence of which is taken as a given. Specific provisions apply to manumission and the status of freedmen, who are referred to as cives Romani liberti, "freedmen who are Roman citizens," indicating that as early as the 5th century BC, former slaves were a significant demographic that the law needed to address, with a legal path to freedom and the opportunity to participate in the legal and political system.[16]

The Roman jurist Gaius described slavery as "the state that is recognized by the ius gentium in which someone is subject to the dominion of another person contrary to nature" (Institutiones 1.3.2, 161 AD).[17] Ulpian (2nd century AD) also regarded slavery as an aspect of the ius gentium, the customary international law held in common among all peoples (gentes). In Ulpian's tripartite division of law, the "law of nations" was considered neither natural law, thought to exist in nature and govern animals as well as humans, nor civil law, the legal code particular to a people or nation.[18] All human beings are born free (liberi) under natural law, but since slavery was held to be a universal practice, individual nations would develop their own civil laws pertaining to slaves.[18] In ancient warfare, the victor had the right under the ius gentium to enslave a defeated population; however, if a settlement had been reached through diplomatic negotiations or formal surrender, the people were by custom to be spared violence and enslavement. The ius gentium was not a legal code,[19] and any force it had depended on "reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct".[20]

Although Rome’s earliest wars were defensive,[21] a Roman victory would still result in the enslavement of the defeated under these circumstances, as is recorded at the conclusion of the war with the Etruscan city of Veii in 396 BC.[22] Defensive wars also drained manpower for agriculture, increasing the demand for labor—a demand that could be met by the availability of war captives.[23] From the sixth through the third centuries BC, Rome gradually became a “slave society,”[24] with the first two Punic Wars (265–201 BC) producing the most dramatic surge in the number of slaves.[25]

Slavery with the possibility of manumission became so embedded in Roman society that by the 2nd century AD, most free citizens in the city of Rome are likely to have had slaves "somewhere in their ancestry."[26]

Enslavement of Roman citizens

In early Rome, the Twelve Tables permitted debt slavery under harsh terms and made freeborn Romans subject to enslavement as a result of financial misfortune. A law in the late 4th century BC put a stop to creditors enslaving a defaulting debtor as a private action, though a debtor could still be compelled by a legal judgment to work off his debt.[27] Otherwise, the only means of enslaving a freeborn citizen that the Romans of the Republican era recognized as lawful was military defeat and capture under the ius gentium.

The Carthaginian leader Hannibal enslaved Roman war captives in large numbers during the Second Punic War. Following the Roman defeat at the Battle of Lake Trasimene (217 BC), the treaty included terms for ransoming prisoners of war. The Roman senate declined to do so, and their commander ended up paying the ransom himself. After the disastrous Battle of Cannae the following year, Hannibal again stipulated a redemption of captives, but the senate after debate again voted not to pay, preferring to send a message that soldiers should fight to victory or die. Hannibal then sold these prisoners of war to the Greeks, and they remained slaves until the Second Macedonian War,[28] when Flamininus recovered 1,200 men who had survived some twenty years of slavery after Cannae. The war that most dramatically escalated the number of slaves brought into Roman society at the same time had exposed an unprecedented number of Roman citizens to enslavement.[29]

In the later Republic and during the Imperial period, thousands of soldiers, citizens, and their slaves in the Roman East were taken captive and enslaved by the Parthians or later within the Sasanian Empire.[30] The Parthians captured 10,000 survivors after the defeat of Marcus Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, and marched them 1,500 miles to Margiana in Bactria, where their fate is unknown.[31] While thoughts of returning the Roman military standards lost at Carrhae motivated military minds for decades, “considerably less official concern was expressed about the liberation of Roman prisoners.”[32] Writing about thirty years after the battle, the Augustan poet Horace imagined them married to "barbarian" women and serving the Parthian army, too dishonored to be restored to Rome.[33]

.jpg.webp)

Valerian became the first emperor to be held captive after his defeat by Shapur I at the Battle of Edessa in AD 260. According to hostile Christian sources, the aging emperor was treated as a slave and subjected to a grotesque array of humiliations.[35] Reliefs and inscriptions located at the sacred Zoroastrian site of Naqsh-e Rostam, southwest Iran, celebrate the victories of Shapur I and his successor over the Romans, with emperors in subjection and legionaries paying tribute.[36] Shapur’s inscriptions record that the Roman troops he had enslaved came from all reaches of the empire.[37]

A Roman enslaved in war under such circumstances lost his citizen rights at home. His right to own property was forfeited, his marriage was dissolved, and if he was head of a household his legal power (potestas) over his dependents was suspended. If he was released from slavery, his citizen status might be restored along with his property and potestas. His marriage, however, was not automatically renewed; another agreement of consent by both parties had to be arranged.[38] The loss of citizenship was a consequence of submitting to an enemy sovereign state; freeborn people kidnapped by bandits or pirates were regarded as seized illegally, and therefore they could be ransomed, or their sale into slavery rendered void, without compromising their citizen status. This contrast between the consequences for status from war (bellum) and from banditry (latrocinium) may be reflected in the similar Jewish distinction between a “captive of a kingdom” and a “captive of banditry,” in what would be a rare example of Roman law influencing the language and formulation of rabbinic law.[39]

The legal process originally developed for reintegrating war captives[40] was postliminium, a return after passing out of Roman jurisdiction and then crossing back over one’s own “threshold” (limen).[41] Not all war captives were eligible for reintegration; the terms of a treaty might permit the other side to retain captives[42] as servi hostium, “slaves of the enemy.”[43] A ransom could be paid to redeem a captive individually or as a group; an individual ransomed by someone outside his family was required to pay back the money before his full rights could be restored, and although he was a freeborn person, his status was ambiguous until the lien was lifted.[44]

An investigative procedure was put in place under the emperor Hadrian to determine whether returned soldiers had been captured or surrendered willingly. Traitors, deserters, and those who had a chance to escape but made no attempt were not eligible for postliminium restoration of their citizenship.[45]

Because postliminium law also applied to enemy seizure of mobile property,[46] it was the means by which military-support slaves taken by the enemy were brought back into possession and restored to their former slave status under their Roman owners.[47]

The slave in Roman law and society

Fundamentally, the slave in ancient Roman law was one who lacked libertas, liberty defined as “the absence of servitude."[48] Cicero (1st century BC) asserted that liberty “does not consist in having a just master (dominus), but in having none.”[49] The common Latin word for "slave" was servus,[lower-alpha 1] but in Roman law, a slave as chattel was mancipium,[50] a grammatically neuter word[51] meaning something "taken in hand," manus, a metaphor for possession and hence control and subordination.[52] Agricultural slaves, certain farmland within the Italian peninsula, and farm animals were all res mancipi, a category of property established in early Rome's rural economy as requiring a formal legal process (mancipatio) for transferring ownership.[53] The exclusive right to trade in res mancipi was a defining aspect of Roman citizenship in the Republican era; free noncitizen residents (peregrini) could not buy and sell this form of property without a special grant of commercial rights.[54]

The Roman citizen who enjoyed liberty to the fullest extent was thus the property owner, the paterfamilias who had a legal right to control the estate. The paterfamilias exercised his power within the domus, the "house" of his extended family, as master (dominus);[55] patriarchy was recognized in Roman law as a form of household-level governance.[56] The head of household was entitled to manage his dependents and to administer ad hoc justice to them with minimal oversight from the state. In early Rome, the paterfamilias had the right to sell, punish, or kill both his children (liberi, the “free ones” in the household) and the slaves of the familia. This power of life and death, expressed as vitae necisque potestas, was exercised over all members of the extended household except his wife[57]— a free Roman woman could own property of her own as a domina, and a married woman's slaves could act as her agents independently of her husband.[58] Despite structural symmetries, the distinction between the father's governance of his children and of his slaves is put bluntly by Cicero: the master can expect his children to obey him readily but will need to "coerce and break his slave."[59]

Although slaves were recognized as human beings (homines, singular homo), they lacked legal personhood (Latin persona).[60] Lacking legal standing as a person, a slave could not enter into legal contracts on his own behalf; in effect, he remained a perpetual minor. A slave could not be sued or be the plaintiff in a lawsuit.[60] The testimony of a slave could not be accepted in a court of law[61] unless the slave was tortured—a practice based on the belief that slaves in a position to be privy to their masters' affairs would be too virtuously loyal to reveal damaging evidence unless coerced,[62] even though the Romans were aware that testimony produced under torture was unreliable.[63] A slave was not permitted to testify against his master unless the charge was treason (crimen maiestatis). When a slave committed a crime, the punishment exacted was likely to be far more severe than for the same crime committed by a free person.[60] Persona gradually became "synonymous with the true nature of the individual" in the Roman world, in the view of Marcel Mauss, but "servus non habet personam ('a slave has no persona'). He has no personality. He does not own his body; he has no ancestors, no name, no cognomen, no goods of his own."[64]

Owing to a growing body of laws, in the imperial period a master could face penalties for killing a slave without just cause and could be compelled to sell a slave on grounds of mistreatment.[60] Claudius decreed that if a slave was abandoned by his master, he became free. Nero granted slaves the right to complain against their masters in a court. And under Antoninus Pius, a master who killed a slave without just cause could be tried for homicide.[65] From the mid to late 2nd century AD, slaves had more standing to complain of cruel or unfair treatment by their owners.[66] But since even in late antiquity slaves still could not file lawsuits, could not testify without first undergoing torture, and could be punished by being burnt alive for testifying against their masters, it is unclear how these offenses could be brought to court and prosecuted; evidence is scant that they were.[67]

Under Constantine II (emperor AD 337–340), Jews were barred from owning Christian slaves, converting their slaves to Judaism, or circumcising their slaves. Laws in late antiquity discouraging the subjection of Christians to Jewish owners suggest that they were aimed at protecting Christian identity,[68] since Christian households continued to have slaves who were Christian.[69]

Marriage and family

In Roman law, the slave had no kinship—no ancestral or paternal lineage, and no collateral relatives.[71] The lack of legal personhood meant that slaves could not enter into forms of marriage recognized under Roman law. However, slaves born into the familia and "upwardly mobile" slaves [72] who held privileged positions might form a heterosexual union with a partner that was intended to be lasting or permanent, within which children might be reared.[73] Such a union, approved and recognized by the slave's owner,[74] was called contubernium. Though not technically a marriage, it had legal implications that were addressed by Roman jurists in case law and expressed an intention to marry if both partners gained manumission.[75] A contubernium was normally a cohabition between two slaves within the same household,[76] and contubernia were recorded along with births, deaths, and manumissions in large households concerned with lineage.[77] Sometimes only one partner (contubernalis) obtained free status before the death of the other, as commemorated in epitaphs.[78] These quasi marital unions were especially common among imperial slaves.[79]

The master would have the legal right to break up or sell off family members, and it has sometimes been assumed that they did so arbitrarily.[80] But because of the value Romans placed on home-reared slaves (vernae) in expanding their familia,[81] there is more evidence that the formation of family units, though not recognized as such for purposes of law and inheritance, was supported within larger urban households and on rural estates.[82] Roman jurists who weigh in on actions that might break up slave families generally favored keeping them together, and protections for them appear several times in the compendium of Roman law known as the Digest.[83] A master who left his rural estate to an heir often included the workforce of slaves, sometimes with express provisions that slave families—father and mother, children, and grandchildren—be kept together.[84]

Among the laws Augustus issued pertaining to marriage and sexual morality was one permitting legal marriage between a freedwoman and a freeborn man of any rank below the senatorial, and legitimizing their heirs.[85] A former slave could not refuse to marry her manumitting owner,[86] who became both her patron and her husband,[87] nor could she divorce him,[88] though otherwise Roman women could initiate divorce.

Peculium

Because they were themselves property (res), as a matter of law Roman slaves could not own property. However, they could be allowed to hold and manage property, which they could use as if it were their own, even though it ultimately belonged to their master.[89] A fund or property set aside for a slave's use was called a peculium. Isidore of Seville, looking back from the early 7th century, offered this definition: “peculium is in the proper sense something which belongs to minors or slaves. For peculium is what a father or master allows his child or slave to manage as his own.”[90]

The practice of allowing the slave a peculium likely originated on agricultural estates in setting aside small parcels of land where slave families could grow some of their own food. The word peculium points to the addition of livestock (pecus). Any surplus could be sold at market. Like other practices that gave slaves a sense of agency and furthered their skills, this early form of peculium served an ethic of self-sufficiency and motivated slaves to be more productive in ways that ultimately benefitted the slave owner, leading over time to more sophisticated opportunities for business development and wealth management for enslaved people.[91]

.jpg.webp)

Slaves within a wealthy household or country estate might be given a small monetary peculium as an allowance.[93] The master's obligation to provide for the slave's subsistence was not counted as part of this discretionary peculium. Growth of the peculium came from the slave's own savings, including profits set aside from what was owed to the master as a result of sales or business transactions conducted by the slave, and anything given to a slave by a third party for "meritorious services".[94] The slave's own earnings could also be the original source of the monetary peculium rather than a grant by the master,[95] and in inscriptions slaves and freedpersons at times assert that they had paid for the dedication with "their own money."[96] The peculium in the form of property could include other slaves put at the disposal of the peculium-holder;[97] in this sense, inscriptions not infrequently record that a slave "belonged to" another slave.[98] Property otherwise could not be owned by the dependents of a household, defined as someone subordinate to the potestas of the paterfamilias—including not only slaves, but adult sons who remained minors by law until their father's death. All wealth belonged to the head of household except for that owned independently by his wife,[99] whose slaves might operate with their own peculia from her.[100]

The legal dodge of peculium enabled both adult sons and capable slaves to manage property, turn a profit, and negotiate contracts.[101] Legal texts do not recognize a fundamental distinction between slaves and sons acting as business agent (institor). However, legal restrictions on making loans to unemancipated sons, introduced in the mid 1st century AD, made them less useful than slaves in this role.[102]

Slaves with the skills and opportunities to earn money might hope to save enough to buy their freedom.[103][104] There was a risk to the still-enslaved person that the master would renege and take back the earnings, but one of the expanded protections for slaves in the Imperial era was that a manumission agreement between the slave and his master could be enforced.[105] While very few slaves ever controlled large sums of money,[106] slaves who managed a peculium had a far better chance of obtaining liberty. With this business acumen, certain freedmen went on to amass considerable fortunes.[107]

Manumission

Slaves were released from their master's control through the legal act of manumissio ("manumission"), meaning literally a "releasing from the hand"[108] (de manu missio).[109] The equivalent act for the releasing of a minor child from their father's legal power (potestas) was emancipatio, from which the English word "emancipation" derives. Both manumission and emancipation would involve transferral of some or most of any peculium (fund or property) the slave or minor had managed, less the self-purchase cost of the slave buying his freedom.[110] That the two procedures are parallel in undoing the control of the paterfamilias is indicated by the legal fiction through which emancipatio occurred: technically, it was a sale (mancipatio) of the minor son three times at once, based on the archaic provision of the Twelve Tables that a son sold three times was freed of his father's potestas.[111][112]

Slaves of the emperor's household (the familia Caesaris) were routinely manumitted at ages 30 to 35—an age that should not be taken as standard for other slaves[113]—the lifestage at which male citizens left adolescence and the well-born entered the "career track" and became eligible to hold public office. Within the familia Caesaris, a young woman in her reproductive years seems to have had the greatest chance for manumission,[114] allowing her to marry and bear legitimate, free children.[115][116] A slave who had a large enough peculium might also buy the freedom of a fellow slave, a contubernalis with whom he had cohabited or a partner in business.[117] Neither age nor length of service was automatic grounds for manumission;[118] "masterly generosity was not the driving force behind the Romans' dealings with their slaves."[119]

Scholars have differed on the rate of manumission.[120] Manual laborers treated as chattel were least likely to be manumitted; skilled or highly educated urban slaves most likely. The hope was always greater than the reality, though it may have motivated some slaves to work harder and conform to the ideal of the "faithful servant." Dangling liberty as a reward, slaveholders could navigate the moral issues of enslaving people through placing the burden of merit on slaves—"good" slaves deserved freedom, and others did not.[121] Manumission after a period of service may have been a negotiated outcome of contractual slavery, though a citizen who had entered willingly into unfree servitude was barred from full restoration of his rights.[122]

There were three kinds of legally binding manumission: by the rod, by the census, and by the terms of the owner's will;[123] all three were ratified by the state.[124] The public ceremony of manumissio vindicta ("by the rod") was a fictitious trial[125] that had to be performed before a magistrate who held imperium; a Roman citizen declared the slave free, the owner did not contest it, the citizen touched the slave with a staff and pronounced a formula, and the magistrate confirmed it.[126] The owner might also free the slave simply by having him entered in the official roll of citizens during census-taking;[127] on principle, the censor had the unilateral power to free any slave to serve the interests of the state as a citizen.[128] Slaves could also be freed in their owner's will (manumissio testamento), sometimes on condition of service or payment before or after freedom.[129] A male slave rewarded with manumission in a will at times also received a bequest, which might include transferring ownership of his contubernalis (informal marriage partner) to him.[130] Heirs might choose to complicate testamentary manumission, as a common condition was that the slave had to buy his freedom from the heir, and a slave still fulfilling the condition of his freedom could be sold. If there was no rightful heir, a master might not only free the slave but make him the heir.[131] A formal manumission could not be revoked by the patron, and Nero ruled that the state had no interest in doing so.[132]

Freedom might also be granted informally, such as per epistulam, in a letter stating this intention, or inter amicos, "among friends," with the owner proclaiming a slave's freedom in front of witnesses. During the Republic, informal manumission did not confer citizen status,[133] but Augustus took steps to clarify the status of those so freed.[134] A law created "Junian Latin" status for these informally manumitted slaves, a sort of "half-way house between slavery and freedom" that, for example, did not confer the right to make a will.[135]

In 2 BC, Augustus restricted the number of slaves that could be freed at once from a single household, depending on the number of slaves belonging to the household. In a household with three to ten slaves, no more than half could be freed; in a household with ten to thirty slaves, no more than a third; in a household with thirty to one hundred slaves, no more than a quarter; and in a household with over one hundred slaves, no more than one-fifth could be freed. Under no circumstances was it permitted to free more than one hundred slaves at a time.[136] Six years later, another law prohibited the manumission of slaves younger than thirty years of age, with some exceptions.[137] Slaves of the emperor's own household were among those most likely to receive manumission, and the usual legal requirements did not apply.[138]

By the early 4th century AD, when the Empire was becoming Christianized, slaves could be freed by a ritual in a church, officiated by an ordained bishop or priest. Constantine I promulgated edicts authorizing manumissio in ecclesia, manumission within a church, in AD 316 and 323, though the law was not put into effect in Africa till AD 401. Churches were allowed to manumit slaves among their membership, and clergy could free their own slaves by simple declaration without filing documents or the presence of witnesses.[139] Laws such as the Novella 142 of Justinian in the 6th century gave bishops the power to free slaves.[140]

Freedmen

A male slave who had been legally manumitted by a Roman citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.[141] A slave who had acquired libertas was thus a libertus ("freed person", feminine liberta) in relation to his former master, who then became his patron (patronus). Freedmen and patrons had mutual obligations to each other within the traditional patronage network, and freedmen could “network” with other patrons as well.[142] An edict in 118 BC stated that the freedman was legally responsible only for services or projects (operae) that had been spelled out as stipulations or sworn to in advance; money could not be demanded, and certain freedmen were exempt from any formal operae.[143] The Lex Aelia Sentia of AD 4 allowed a patron to take his freedman to court for not carrying out his operae as outlined in their manumission agreement, but the possible penalties—which range in severity from a reprimand and fines to condemnation to hard labor—never include a return to enslavement.[144]

As a social class, freed slaves were libertini, though later writers used the terms libertus and libertinus interchangeably.[145][146] Libertini were not entitled to hold the "career track" magistracies or state priesthoods in the city of Rome, nor could they achieve senatorial rank.[147] But they could hold neighborhood and local offices which entitled them to wear the toga praetexta, ordinarily reserved for those of higher rank, for ceremonial functions and their funeral rites.[148] In the towns (municipia) of the provinces and later in towns with the status of colonia, inscriptions indicate that former slaves could be elected to all offices below the rank of praetor—a fact obscured by elite literature and ostensible legal barriers.[149] Ulpian even holds that if a fugitive slave managed to be elected praetor, his legal acts would remain valid if his true status were discovered, because the Roman people had chosen to entrust him with power.[150] Limitations were placed only on the former slaves themselves and did not apply to their sons.[151]

During the early Imperial period, some freedmen became very powerful. Those who were part of the emperor's household (familia Caesaris) could become key functionaries in the government bureaucracy. Some rose to positions of great influence, such as Narcissus, a former slave of the emperor Claudius. Their influence grew to such an extent under the Julio-Claudian emperors that Hadrian limited their participation by law.[147]

More typical among freedmen success stories would be the cloak dealership of Lucius Arlenus Demetrius, enslaved from Cilicia, and Lucius Arlenus Artemidorus, from Paphlagonia, whose shared family name suggests that their partnership toward a solid, profitable business began during enslavement.[152] A few freedmen became very wealthy. The brothers who owned the House of the Vettii, one of the biggest and most magnificent houses in Pompeii, are thought to have been freedmen.[153] Building impressive tombs and monuments for themselves and their families was another way for freedmen to demonstrate their achievements.[154] Despite their wealth and influence, they might still be looked down on by the traditional aristocracy as a vulgar nouveau riche. In the Satyricon, the character Trimalchio is a caricature of such a freedman.[155]

Dediticii

Although in general freed slaves could become citizens, those categorized as dediticii held no rights even if freed. The jurist Gaius called the status of dedicitius "the worst kind of freedom."[156] Slaves whose masters had treated them as criminals—placing them in chains, tattooing or branding them, torturing them to confess a crime, imprisoning them, or sending them involuntarily to a gladiatorial school (ludus) or condemning them to fight with gladiators or wild beasts—if manumitted were counted as a potential threat to society along with enemies defeated in war,[157] regardless of whether their master's punishments had been justified. If they came within a hundred miles of Rome,[lower-alpha 2] they were subject to reenslavement.[158] They were excluded from the universal grant of Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire made by Caracalla in AD 212.[159]

Enslavement

"Slaves are either born or made" (servi aut nascuntur aut fiunt):[160] in the ancient Roman world, people might become enslaved as a result of warfare, piracy and kidnapping, or child abandonment—the fear of falling into slavery, expressed frequently in Roman literature, was not just rhetorical exaggeration.[161] A significant number of the enslaved population were vernae, born to a slave woman within a household (domus) or on a family farm or agricultural estate (villa). A few scholars have suggested that citizens selling themselves into slavery was a more frequent occurrence than literary sources alone would indicate.[162] The relative proportion of these sources of enslavement within the slave population is hard to determine and remains a subject of scholarly debate.[163]

War captives

During the Republic, warfare was arguably the greatest source of slaves,[164] and certainly accounted for the marked increase in the number of slaves held by Romans during the Middle and Late Republic.[165] A major battle might result in captives numbering in the hundreds to the tens of thousands.[166][167] The newly enslaved were bought wholesale by dealers who followed the Roman armies.[168] During the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar once sold the entire population of a conquered oppidum (walled town), numbering 53,000 people, to slave dealers on the spot.[169]

Warfare continued to produce slaves for Rome throughout the Imperial period,[170] though war captives arguably became less important as a source after the major campaigns of Augustus concluded later in his life.[171] The smaller-scale, less continual warfare of the so-called Pax Romana of the 1st and 2nd centuries still produced slaves “in more than trivial numbers.”[172]

As an example of the impact on one community, it was during this period that the greatest numbers of slaves from the province of Judaea were traded, as a result of the Jewish–Roman wars (AD 66–135).[173] Josephus reports that the first Jewish revolt of AD 66–70 alone resulted in the enslavement of 97,000 people.[174] The future emperor Vespasian enslaved 30,000 in Tarichea after executing those who were old or infirm.[175] When his son and future successor Titus captured the city of Japha, he killed all the males and sold 2,130 women and children into slavery.[176] What appears to have been a unique instance of over-supply in the Roman market for slaves occurred in AD 137 after the Bar Kokhba revolt was quashed and more than 100,000 slaves were put on the market. A Jewish slave for a time could be bought at Hebron or Gaza for the same price as a horse.[177]

The demand for slaves may account for some expansionist actions that seem to have no other political motive—Britain, Mauretania, and Dacia may have been desirable conquests primarily as sources of manpower, and so too Roman campaigns across the frontiers of their African provinces.[178]

The Digest offers an etymology that connects the word servus for "slave" to war captivity as an alternative to slaughtering the defeated: "Slaves (servi) are so called because commanders sell captives and through this make it usual to save (servare) and not kill them."[179] Julius Caesar concluded his campaign against the Gallic Veneti by executing their senate but sold the survivors sub corona, "under the wreath."[180] It was thought that war captives were customarily sold sub corona[181] because in early times they would have been wreathed[182] like a sacrificial victim[183] (hostia, which Ovid relates to hostis, "enemy"[184]). The cultural assumption that enslavement was a natural result of defeat in war is reflected in the ubiquity of Imperial art depicting captives, an image that appears not only in public contexts that serve overt purposes of propaganda and triumphalism but also on objects that seem intended for household and personal display, such as figurines, lamps, Arretine pottery, and gems.[185]

Piracy and kidnapping

Piracy has a long history in human trafficking.[186] The primary goal of kidnapping was not enslavement but maximizing profit,[187] as the relatives of captives were expected to pay ransom.[188] If a slave was kidnapped, the owner might or might not decide that the amount of ransom was worthwhile.[189] Although people who cared about getting the captive back were motivated to pay more than a stranger would for a slave at auction, where the captive’s individual qualities would determine pricing, they were sometimes unable to come up with the amount demanded. If multiple people from the same city were taken at the same time and demands for payment could not be met privately, the home city might try to pay the ransom from public funds, but these efforts too might come up short.[190] The captive could then resort to borrowing the ransom money from profiteering lenders, in effect putting himself into debt bondage to them. Selling the kidnap victim on the open market was a last but not infrequent resort.[191]

No traveler was safe; Julius Caesar himself was captured by Cilician pirates as a young man. When the pirates realized his high value, they set his ransom at twenty talents. As the story came to be told, Caesar insisted that they raise it to fifty. He spent thirty-eight days in captivity as they waited for the ransom to be delivered.[192] Upon release, he is said to have returned and subjected his captors to the form of execution by custom reserved for slaves, crucifixion.[193]

Within the Jewish community, rabbis usually encouraged buying back enslaved Jews, but advised that “one should not ransom captives for more than their value, for the good order of the world” because inflated ransoms would only “motivate Romans to enslave even more Jews”.[194] In the early Church, ransoming captives was considered a work of charity (caritas), and after the Empire came under Christian rule, churches spent “enormous funds” to buy back Christian prisoners.[195]

Systematic piracy for the purpose of human trafficking was most rampant in the 2nd century BC, when the city of Side in Pamphylia (present-day Turkey) was a center of the trade.[196] Pompey was credited with eradicating piracy from the Mediterranean in 67 BC,[197] but actions were taken against Illyrian pirates in 31 BC following Actium,[198] and piracy was still a concern addressed during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius. While large-scale piracy was largely controlled during the Pax Romana, piratical kidnapping continued to contribute to the Roman slave supply into the later Imperial era, though it may not have been a major source of new slaves.[199] In the early 5th century AD, Augustine of Hippo was still lamenting wide-scale kidnapping in North Africa.[200] The Christian missionary Patricius, from Roman Britain, was kidnapped by pirates around AD 400 and taken as a slave to Ireland, where he continued work that eventually led to his canonization as Saint Patrick.[201]

Vernae

.jpg.webp)

By the common law of nations (ius gentium), the child of a legally enslaved mother was born a slave.[202] The Latin word for a slave born within the familia of a household (domus) or agricultural estate (villa) was verna, plural vernae.

There was a stronger social obligation to care for vernae, whose epitaphs sometimes identify them as such, and at times they would have been the biological children of free males of the household.[203][204] Frequent mention of vernae in literary sources indicates that home-reared slaves not only were preferred to those obtained in slave markets but received preferential treatment. Vernae were more likely to be allowed to cohabit as a couple (contubernium) and rear their own children.[205] A child verna might be reared alongside the owner's own child of the same age, even sharing the same wet-nurse.[206] They had greater opportunities for education and might be educated along with the freeborn children of the household.[207] Many "intellectual slaves" were vernae.[208] A dedicatory inscription dating to AD 198 lists the names of twenty-four imperial freedmen who were teachers (paedagogi); six are identified as vernae.[209] The use of verna in the epitaphs of freedmen suggests that former slaves might take pride in their birth within a familia.[210]

Some scholars think that the majority of slaves in the Imperial period were vernae or that domestic reproduction was the single most important source of slaves; modern estimates depend on the interpretation of often uncertain data, including the overall number of slaves.[211]

Alumni

Children brought into a household to be fostered without formal adoption[lower-alpha 3] were alumni (plural; feminine alumnae), "those who have been nurtured," a term that is not used to refer to infants or foundlings.[212] Even if cared for lovingly, alumni often had an ambiguous legal status. Of attested alumni, only about a quarter can be securely identified as slaves;[213] their place in the familia of the household seems similar to that of vernae. Inscriptions suggest that manumission was frequent for alumni.[214]

Child labor

In families that had to work, whether technically free or enslaved, children could begin acquiring work habits as early as age five, when they became developmentally capable of carrying out small tasks.[215] The transitional period from early childhood (infantia) to functional childhood (pueritia) occurred among the Romans from the ages of five to seven, with the upper classes enjoying a more prolonged and sheltered infantia and pueritia, as in most cultures.[216] In general, ten was the age at which child slaves were regarded as useful enough to be traded as such.[217] Among working people of some means, a child slave might be an investment; an example from the juristic Digest is a metalsmith who buys a child slave, teaches him the trade, and then sells him at double the original price paid.[218] Apprenticeship contracts exist for free and slave children, with few differences in terms between the two.[219]

Training for skilled work typically started at ages 12 to 14, lasting six months to six years, depending on the occupation.[220] Jobs for which child slaves apprenticed include textile production, metalworking such as nail-making and coppersmithing, mirror-making, shorthand and other secretarial skills, accounting, music and the arts, baking, ornamental gardening, and construction techniques.[221] Incidental mentions in literary texts suggest that training programs were methodical: boys learned to be barbers by using a deliberately blunt razor.[222]

In wealthy, socially active households of the Imperial era, prepubescent children (impuberes) were trained for serving food, as their sexual purity was thought to confer hygienic benefits.[223] A capsarius was a child attendant who went to school with the master's children, carrying their things and attending lessons with them.[224] Large households might train their own staff, some even running in-house schools, or send slaves ages 12 to 18 to paedagogia, imperially run vocational schools providing skills and refinement.[225] Adolescent slaves as young as 13 might be capably employed in accounting and other office work, as well as serving as heralds, messengers, and couriers.[226]

Performing arts troupes were a mix of free and enslaved people that might tour independently or be sponsored by a household, and children are widely attested among the entertainers. Some of the youngest performers are gymnici, acrobats or artistic gymnasts. Child slaves are also found as dancers and singers, preparing as professionals for popular forms of musical theater.[227]

Typically on a farm, children start helping out with age-appropriate tasks quite early. Ancient sources that mention very young children born into rural slavery have them feeding and tending chickens or other poultry,[228] picking up sticks, learning how to weed, gathering apples,[229] and minding the farm's donkey.[230] Young children were not expected to work all day long.[231] Older children might tend small flocks of animals that were driven out in the morning and returned before nightfall.[232]

Modern-era mining employed child labor into the early 20th century, and there is some evidence that children worked in certain kinds of ancient Roman mining. Impuberes documented at mines that mostly relied on free workers are likely to be part of mining families, though wax tablets from a mine in Alburnus Maior records the purchase of two children, ages 6 and 10 (or 15).[233] Children seem to have been employed especially in gold mines, crawling into the narrowest parts of shafts to retrieve loose ore,[234] which was passed to the outside in baskets hand to hand.[235]

Osteoarchaeology can identify adolescents and children as working alongside adults, but not whether they were free or enslaved.[236] Children can be difficult to distinguish from slaves both in verbal sources, as puer could mean either "boy" or "male slave" (pais in Greek), and in art, as slaves were often depicted as smaller in proportion to free subjects to show their lesser status, and children older than infants and toddlers often look like small adults in art.[237] Since as a matter of Roman law, a father had the right to contract out all dependents of a household for labor, among workers who were still minors there is often little practical difference between free and slave.[238]

Child abandonment

Scholarly views vary on the extent to which child abandonment in its several forms was a significant source for potential slaves.[239] The children of poor citizens who were left orphaned were vulnerable to enslavement, and children brought into a household to be fostered as alumni often had an ambiguous legal status. A tradesman might foster an abandoned child as an alumnus and apprentice him, an arrangement that does not preclude affection and could result in passing along the business with an expectation of care in old age.[240]

However, slave traffickers would have preyed on neglected children who were old enough to be out and about on their own, enticing them with "sweets, cakes, and toys".[241] Child slaves obtained in this way were especially in danger of being reared as prostitutes or gladiators or even being maimed to make them more pitiable as beggars.[242]

Infant exposure

.jpg.webp)

Child abandonment, whether through the death of family or intentionally, is to be distinguished from infant exposure (expositio), which the Romans seem to have practiced widely and which is embedded in the founding myth of the exposed twins Romulus and Remus suckling at the she-wolf. Families who could not afford to raise a child might expose an unwanted infant—usually imagined as abandoning it under outdoor conditions that were likely to cause its death, thus a means of infanticide.[243] A serious birth defect was considered grounds for exposure even among the upper classes.[244] One view is that healthy infants who survived exposure were usually enslaved and were even a significant source of slaves.[245]

A healthy exposed infant might be taken in for fosterage or adoption by a family, but even this practice could treat the child as an investment: if the birth family later wished to reclaim their offspring, they were entitled to do so but had to reimburse expenses for nurturance.[246] Traffickers also could pick up surviving infants and rear them with training as slaves,[247] but since children under the age of five are unlikely to provide much labor of value,[248] it is unclear how investing the five years of adult labor in nurturing would be profitable.[249]

Infant exposure as a source of slaves also assumes predictable sites where traders could expect a regular "harvest"; successful births would be most concentrated in urban environments, and likely sites for infant depositories are temples and other religious sites such as the obscure Columna Lactaria, the “Milk Column” landmark about which little is known.[250] The satirist Juvenal writes of supposititious children taken up from the dregs to the bosom of the goddess Fortuna, who laughs as she sends them off to the great houses of noble families to be quietly reared as their own.[251] Large households staffed wet nurses and other childcare attendants who would share childrearing duties for alumni and all infants of the household, free or slave.[252]

Some parents may have arranged to hand over the neonate directly for payment as a sort of ex post facto surrogacy.[253] Constantine, the first Christian emperor, formalized the buying and selling of newborns during the first hours of life,[254] when the newborn was still sanguinolentus, bloody before the first bath. At a time when infant mortality might have been as high as 40 percent,[255] the newborn was thought in its first week of life to be in a perilous liminal state between biological existence and social birth,[256] and the first bath was one of many rituals marking this transition and supporting the mother and child.[257] The Constantinian law has been viewed as an effort to stop the practice of exposure as infanticide[258] or as "an insurance policy on behalf of individual slave-owners"[259] designed to protect the property of those who, unknowingly or not, had bought an infant later claimed or shown to have been born free.[260] In the historical period, expositio may actually have become a legal fiction whereby the parents surrendered the newborn during the first week of life, before it had been ritually accepted and legally registered as part of the birth family, and transferred potestas over the infant to the new family from the beginning of its life.[261]

Parental sale

The ancient right of patria potestas entitled fathers to dispose of their dependents as they saw fit. They could sell their children just as they did slaves, though in practice, the father who sold his child was likely too impoverished to own slaves. The father relinquished his power (potestas) over the child, who entered the possession (mancipium) of a master.[262] A law of the Twelve Tables (5th century BC) limited the number of times a father could sell his children: a daughter only once, but a son as many as three. This kind of serial selling only of the son suggests nexum, a temporary obligation as a result of debt which was formally abolished by the end of the 4th century BC.[263] A dodge around freeborn status that continued into late antiquity was to lease the minor child's labor up to age 20 or 25, so that the holder of the lease did not own the child as property but had full-time use through the legal transfer of potestas.[264]

Roman law thus grappled with the tensions among the supposed sanctity of free birth, patria potestas, and the reality[265] that parents might be driven by poverty or debt to sell their children.[266] Potestas meant that there was no legal penalty for the parent as seller.[267] The sales contract itself was always technically void because of the traded child's free status, which if unknown to the buyer entitled him to a refund.[268] Even if the sale had not been contracted as temporary, parents who came into better days could restore their children to free status by paying the original sale price plus 20 percent to cover the costs of their care during servitude.[269]

Most parents would have sold their children only under extreme duress.[270] In the mid-80s BC, parents in the province of Asia said they were forced to sell their children in order to pay the heavy taxes levied by Sulla as proconsul.[271] In late antiquity, selling off the family's children was viewed in Christian rhetoric as a symptom of moral decay caused by taxation, moneylenders, the government, and prostitution.[272] Sources that moralize from an upper-class perspective about parents selling children may at times be misrepresenting contracts for apprenticeships and labor that were necessary for wage-earning families, especially since many of these were arranged by mothers.[273]

The Christianization of the later empire shifted priorities within the inherent contradictions of this legal framework. Constantine, the first Christian emperor, tried to alleviate hunger as one condition that led to child-selling by ordering local magistrates to distribute free grain to poor families,[274] later abolishing the "power of life and death" the paterfamilias had held.[275]

Debt slavery

Nexum was a debt bondage contract in the early Roman Republic. Within the Roman legal system, it was a form of mancipatio. Though the terms of the contract would vary, essentially a free man pledged himself as a bond slave (nexus) as surety for a loan. He might also hand over his son as collateral. Although the bondsman could expect to face humiliation and some abuse, as a citizen under the law he was supposed to be exempt from corporal punishment. Nexum was abolished by the Lex Poetelia Papiria in 326 BC.

Roman historians illuminated the abolition of nexum with a traditional story that varied in its particulars; broadly, a nexus who was a handsome, upstanding youth suffered sexual harassment by the holder of the debt. The cautionary tale highlighted the incongruities of subjecting one free citizen to another's use, and the legal response was aimed at establishing the citizen's right to liberty (libertas), as distinguished from the slave or social outcast (infamis).[276]

Although nexum was abolished as a way to secure a loan, a form of debt bondage might still result after a debtor defaulted.[277] It remained illegal to enslave a free person for this reason or to pledge a minor to secure a parent's debt, and the legal penalties attached to the creditor, not the debtor.[278]

Self-sales

The liberty of the Roman citizen was an "inviolable" principle of Roman law, and therefore it was illegal for a freeborn person to sell himself[279]—in theory. In practice, self-enslavement might be overlooked unless one of the parties took issue with the terms of the contract.[280] "Self-sales" are not well represented in Roman literature, presumably because they were shameful and against the law.[281] The limited evidence is primarily to be found in Imperial legal sources, which indicate that “self-sale” as a path to enslavement was as well recognized as being captured in war or being born to an enslaved mother.[282]

Self-sales are in evidence mainly when challenged in court on grounds of fraud. A case for fraud could be made if the seller or the buyer knew that the enslaved person was freeborn (ingenuus) at the time of sale when the trafficked person himself did not. Fraud could also be alleged if the person sold had been under the age of twenty. Legal argumentation makes it clear that protecting the buyer’s investment was a priority, but if either of these circumstances was proved, the liberty of the enslaved person could be reclaimed.[283]

Since it was difficult to prove who knew what when, the most solid evidence for voluntary enslavement was whether the formerly free person had consented by receiving a share of the proceeds from the sale. A person who knowingly surrendered the rights of Roman citizenship was thought unworthy of holding them, and permanent enslavement was thus considered an appropriate consequence.[284] Self-sale by a Roman soldier would be a form of desertion,[285] and execution was the penalty.[286] Enslaved Roman prisoners of war were similarly deemed ineligible to have their citizenship restored if they had surrendered their liberty without fighting hard enough to keep it (see the enslavement of Roman citizens above); as the Roman Republic devolved, political rhetoric feverishly urged citizens to resist the shame of falling into "slavery" under one-man rule.[287]

However, self-sale cases that made it to the level of imperial appeal often resulted in voiding the contract,[284] even if the enslaved person had consented, as a private contract did not override the state’s interest in regulating citizenship, which carried tax obligations.[288]

The slave economy

During the period of Roman imperial expansion, the increase in wealth amongst the Roman elite and the substantial growth of slavery transformed the economy.[289] Although the economy was dependent on slavery, Rome was not the most slave-dependent culture in history. Among the Spartans, for instance, the slave class of helots outnumbered the free by about seven to one, according to Herodotus.[290] Economic historian Peter Temin has argued that "Rome had a functioning labor market and a unified labor force" in which slavery played an integral role. The condition of mobility required for market dynamism was met by the number of free workers seeking wages and skilled slaves with an incentive to earn.[291] Wages could be earned by both free and some enslaved workers, and fluctuated in response to labor shortages.[292] In any case, scholars differ on how the particulars of Roman slavery as an institution can be framed within theories of labor markets in the overall economy.[293][294][295]

Multitudes of slaves who were brought to Italy were purchased by wealthy landowners in need of large numbers of slaves to labour on their estates. Historian Keith Hopkins noted that it was land investment and agricultural production which generated great wealth in Italy, and considered that Rome's military conquests and the subsequent introduction of vast wealth and slaves into Italy had effects comparable to widespread and rapid technological innovations.[296]

The slave trade

What the Roman jurist Papinian referred to as "the regular, daily traffic in slaves"[297] involved every part of the Roman Empire and occurred across borders as well. The trade was only lightly regulated by law.[298] Slave markets seem to have existed in most cities of the Empire, but outside Rome the largest center was Ephesus.[299] The major centers of the Imperial slave trade were in Italy, the north Aegean, Asia Minor, and Syria. Mauretania and Alexandria were also significant.[300]

The largest market on the Italian peninsula, as might be expected, was the city of Rome,[301] where the most notorious slave-traders set up shop next to the Temple of Castor at the Forum Romanum.[302] Puteoli may have been the second busiest.[303] Trading also occurred at Brundisium,[304] Capua,[305] and Pompeii.[306] Slaves were imported from across the Alps to Aquileia.[307]

The rise and fall of Delos is an example of the volatility and disruptions of the slave trade. In the eastern Mediterranean, policing by the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Rhodes had kept some check on piratical kidnapping and illegal slave trading until Rome, on the wave of their unexpected success against Carthage, expanded trade and exerted dominance eastward.[308] The long-established port of Rhodes, known as a "law and order" state, had legal and regulatory barriers to exploitation by the new Italian "entrepreneurs",[309] who got a more porous reception in Delos as they set up shop in the latter 3rd century BC.[310] To disadvantage Rhodes, and ultimately devastating its economy,[311] in 166 BC the Romans declared Delos a free port, meaning that merchants there would no longer have to pay the 2 percent customs tax.[312] The piratical slave trade then flooded into Delos "with no questions asked" about the source and status of captives.[313] While the geographer Strabo's figure of 10,000 slaves traded daily is more hyperbole than statistic,[314] slaves became the number one Delian commodity.[315] The large commercial agricultural operations in Sicily (latifundia) likely received great numbers of Delian-traded Syrian and Cilician slaves, who went on to lead the years-long slave rebellions of 135 and 104 BC.[316]

But as the Romans established better-located and more sophisticated trading centers in the East, Delos lost its privilege as a free port and was left to be sacked in 88 and 69 BC during the Mithridatic Wars, from which it never recovered.[317] Other cities such as Mytilene may have taken up the slack.[318] The Delian slave economy had been artificially exuberant,[319] and by averting their gaze the Romans exacerbated the piracy problem that would vex them for centuries.[320]

Major sources of slaves from the East include Lydia, Caria, Phrygia, Galatia, and Cappadocia, for which Ephesus was a center of trade.[321] Aesop, the Phrygian writer of fables, was supposed to have been sold at Ephesus.[322] Pergamum is likely to have had "regular and heavy" slave trading,[323] as is the prosperous city of Acmonia in Phrygia.[324] Strabo (1st century AD) describes Apameia in Phrygia as ranking second in trade only to Ephesus in the region, observing that it was “the common warehouse for those from Italy and from Greece”—a center for imports from the west, with slaves the most likely commodity for export trade.[325] Markets are also likely to have existed in Syria and Judaea, though direct evidence is thin.[326]

In the north Aegean, a large memorial to a slave trader in Amphipolis suggests that this might have been a location where Thracian slaves were traded.[327] Byzantium was a market for the Black Sea slave trade.[328] Slaves coming from Bithynia, Pontus, and Paphlagonia would have been traded in the cities of the Propontis.[329]

.jpg.webp)

Roman coin hoards dating from the 60s BC are found in unusual abundance in Dacia (present-day Romania), and have been interpreted as evidence that Pompey’s success in shutting down piracy caused an increase in the slave trade in the lower Danube basin to meet demand. The hoards drop off in frequency for the 50s BC, when Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul were resulting in large lots of new slaves brought to market, and resurge in the 40s and 30s.[331] Archaeology into the 21st century has continued to produce evidence of slave trafficking in parts of the Empire where it had been little attested, such as Roman London.[332]

Slaves were traded from outside Roman borders at several points, as mentioned by literary sources such as Strabo and Tacitus and attested by epigraphical evidence in which slaves are listed among commodities subject to tariffs.[333] The readiness of Thracians to exchange slaves for the necessary commodity of salt became proverbial among the Greeks.[334] Diodorus Siculus says that in pre-conquest Gaul, wine merchants could trade an amphora for a slave; Cicero mentions a slave trader from Gaul in 83 BC.[335] Walter Scheidel conjectured that "enslavables" were traded across borders from present-day Ireland, Scotland, eastern Germany, southern Russia, the Caucasus, the Arab peninsula, and what used to be referred to as "the Sudan"; the Parthian Empire would have consumed most supply to the east.[336]

Auctions and sales

William V. Harris outlines four market venues for slave trading:

- small-scale transactions owner-to-owner in which a single slave might be traded;

- the “opportunistic market”, such as the slave traders who followed the army and handled large numbers of slaves;

- fairs and markets in small towns, where slaves would’ve been among various goods exchanged;

- slave markets in major cities, where auctions were held on a regular basis.[337]

Slaves traded on the market were empticii ("purchased ones"), as distinguished from home-reared slaves born within the familia. Empticii were most often bought cheap for everyday tasks or labor, but some were thought of as a kind of luxury good and brought high prices, if they possessed a sought-after, specialized skill or a special quality such as beauty.[338] Most of the slaves traded on the market were in their teens and twenties.[339] In Diocletian’s edict on price controls (301 AD), a maximum price for skilled slaves aged 16–40 is fixed as up to double that of an unskilled slave, which was the equivalent of 3 tons of wheat for a male and 2.5 for a female.[340] Actual pricing would differ by time and place.[341] Evidence for real prices is rare and known mostly from papyri documents preserved in Roman Egypt,[342] where the practice of slavery may not be typical of Italy or the empire as a whole.

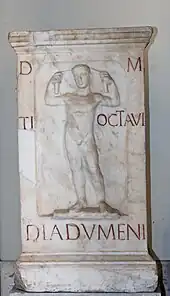

From the mid-1st century BC, the edict of the aediles, who had jurisdiction over market transactions,[344] had a section aimed at protecting buyers of slaves by requiring any disease or defect to be divulged at time of sale.[345] Information about the slave was either written on a tablet (titulus) hung from the neck[346] or called out by the auctioneer.[347] The slave being auctioned might be placed on a stand for viewing.[lower-alpha 4] Prospective buyers could feel the slave, have them move or jump, or ask for them to be undressed to make sure the dealer wasn't concealing a physical defect.[350] The wearing of a particular cap (pilleus) marked a slave who didn't come with a warranty;[351][352] chalk-whitened feet were a sign of foreigners newly arrived in Italy.[353]

A rare depiction of an auction, on a funeral monument from about the same time as the edict, shows a male slave wearing a loincloth and possibly shackles and standing on a pedestal- or podium-like structure.[354] To the left is an auctioneer (praeco);[355] the gesturing, toga-wearing figure to the right may be a buyer asking questions.[356] The monument was set up by a familia of former slaves, the Publilii, who were either depicting their own history or, like many freedmen, expressing pride in conducting their own business successfully and honestly.[357]

If defects were fraudulently concealed, a six-month return policy required the dealer to take back the slave and issue a refund, or to make a partial refund during an extended warranty of twelve months.[358][359] Roman jurists closely parsed what might constitute a defect—not, for instance, missing teeth, since perfectly healthy infants, it was reasoned, lack teeth.[360] Slaves who were sold for a single price as a functional unit, such as a theatre troupe, could be returned as a group if one proved to be defective.[361]

Although slaves were property (res), as human beings they were not to be considered merchandise (merces); those who sold them therefore were not merchants or traders (mercatores) but sellers (venalicarii).[362]

Slave-traders

The Latin word for slave-trader was venalicius or venalicarius (from venalis, "something that can be bought," especially as a substantive, a human being for sale)[363] or mango, plural mangones,[364] a word of likely Greek origin[365] that had connotations of "huckster";[366] in Greek more bluntly somatemporos, a dealer in bodies.[367] Slave-traders had a reputation for dishonesty and deceptive practices, but most of the moral judgments are about defrauding customers rather than the welfare of the slaves.[368] While the senatorial class disdained commerce in general as sordid,[369] rhetoric reviling slave-traders in particular is found widely in Latin literature.[370] Although slaves play leading roles in the comedies of Plautus, no major character is a slave-trader.[371]

Professional slave-traders are rather shadowy figures, as their social standing and identities are not well documented in ancient sources.[372] They appear to have formed trade organizations (societates) that lobbied for legislation and perhaps also for the purpose of raising investment capital.[373] Most of those known by name are Roman citizens;[374] of these, most are freedmen.[375] Only a few slave-traders receive prominent mention by name in literature; one Toranius Flaccus was considered a witty dinner companion and socialized with the future emperor Augustus.[376] Mark Antony relied on Toranius as a procurer of female slaves, and even forgave him upon learning that the supposedly twin boys he had purchased were in fact not consanguineous, the mango having persuaded the triumvir that their identical appearance was therefore all the more remarkable.[377]

A few slave-traders were comfortable enough with their occupation that they had themselves identified as such in their epitaphs.[378] Others are known from inscriptions recognizing them as benefactors, indicating that they were prosperous and locally prominent.[379] The Genius venalicii, an obscure guardian spirit to do with the slave market, is honored presumably by slave-traders in four inscriptions, one of which is dedicated to this genius in the company of Dea Syria, perhaps reflecting the heavy trade in Syrian slaves from which arose a Syrian neighborhood in the city of Rome.[380] The cultivation of various genii was an everyday feature of classical Roman religion; the Genius venalicii normalizes the trade in slaves as like any other prosperity-seeking marketplace.[381]

Slaves were also sold widely by people who made their main living in other ways and by merchants dealing primarily in other goods.[382] In late antiquity, itinerant Galatians protected by powerful patrons become prominent in the North African trade.[383] Although elite owners generally acquired slaves through intermediaries,[384] some may have been more directly involved than literary sources like to acknowledge. When the future emperor Vespasian returned bankrupt from his proconsulate in Africa, he is thought to have restored his fortunes by trading in slaves, possibly specializing in eunuchs as a luxury good.[385]

Taxes and tariffs

During the Republic, the only regular revenue from slaveholding collected by the state was a tax placed on manumissions starting in 357 BC, amounting to 5 percent of the slave's estimated value.[386] In 183 BC, Cato the Elder as censor placed a sumptuary tax on slaves that had cost 10,000 asses or more, calculated at a rate of 3 denarii per 1,000 asses on an assessed value ten times the purchase price.[387] In 40 BC, the triumvirs attempted to impose a tax on slave ownership, which was squelched by "bitter opposition."[388]

In AD 7, Augustus imposed the first tax on Roman citizens as purchasers of slaves,[389] at a rate of 2 percent, estimated to generate annual revenues of about 5 million sesterces—a figure that may indicate some 250,000 sales.[299] By comparison, the sales tax on slaves in Ptolemaic Egypt had been 20 percent.[390] The slave-sales tax was increased under Nero to 4 percent,[391] with a misguided attempt to divert the burden to the seller, which only increased prices.[392]

Tariffs on slaves imported to or exported from Italy were taken at harbor customs, as they were all around the Empire.[393] In AD 137, for example, the customs dues in Palmyra for teenage slaves was 2 to 3 percent of value.[394] At Zaraï in Roman Numidia, the tariff for a slave was the same as for a horse or mule.[395] A law of the censors exempted the paterfamilias from paying harbor tax at Sicily on servi brought into Italy for his direct employment in a wide range of roles, indicating that the Romans saw a difference between obtaining slaves who were to be incorporated into the life of the household and those traded for profit.[396]

Types of work

Slaves worked in a wide range of occupations that can be roughly divided into five categories: household or domestic, imperial or public, urban crafts and services, agriculture, and mining.[397] Both free and enslaved labor was employed for nearly all forms of work, though the proportion of free workers to slaves might vary by task and at different time periods. Regardless of the status of the worker, labor in the service of another was regarded as a form of submission in the ancient world,[398] and Romans of the governing class regarded wage-earning as equivalent to slavery.[399]

Household slaves

Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,[397] including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (ancilla), launderer, wet nurse or nursery attendant, teacher, secretary, seamstress, accountant, and physician.[296] For large households, job descriptions indicate a high degree of specialization: handmaids might be assigned to the upkeep, storage, and readiness of the mistress's wardrobe or specifically mirrors or jewelry.[400] Rich households with specialists who might not be needed full-time year round, such as goldsmiths or furniture painters, might lease them out to friends and desirable associates or give them license to run their own shop as part of their peculium.[401]

In Roman Egypt, papyri preserve apprenticeship contracts written in Greek that indicate the training a worker might require to become skilled, usually for a full year. A beautician (ornatrix) required a three-year apprenticeship; in one Roman legal case, it was ruled that a slave who had studied for only two months could not be considered an ornatrix as a matter of law.[402]

In the Imperial era, a large elite household (a domus in town, or a villa in the countryside) might be supported by a staff of hundreds;[397] or on the lower end of scholarly estimates, perhaps an average of 100 slaves per domus during the time of Augustus. Possibly half the slaves in the city of Rome served in the houses of the senatorial order and of the richer equestrians.[403] The living conditions of the familia urbana—slaves attached to a domus—were sometimes superior to those of many free urban poor in Rome,[404] though even in the grandest houses, they would have lived "packed in to basement rooms and odd crannies."[405] Still, household slaves likely enjoyed the highest standard of living among Roman slaves, next to publicly owned slaves in administration, who were not subject to the whims of a single master.[358]

Urban crafts and services

Of slaves in the city of Rome not attached to a domus, most were engaged in trades and manufacturing. Occupations included fullers, engravers, shoemakers, bakers, and mule drivers. The Roman domus itself should not be thought of as a "private" home in the modern sense, as business was often conducted there, and even commerce—the first-floor rooms facing the street might be shops used or rented out as commercial spaces.[406] The work done or the goods made and sold by enslaved labor from these storefronts complicates the distinction between household and general urban labor.

Through the end of the 2nd century BC, skilled labor throughout Italy, such as pottery design and manufacture, was still predominated by free workers, whose corporations or guilds (collegia) might own a few slaves.[407] In the Imperial era, as many of 90 percent of workers in these areas might be slaves or former slaves.[408]

Training programs and apprenticeships are well if briefly documented. Slaves whose ability was noticed might be trained from a young age in trades requiring a high degree of artistry or expertise; for example, an epitaph mourns the premature death of a talented boy, only age 12, who was already apprenticing as a goldsmith.[409] Girls might be apprenticed particularly in the textile industry; contracts specify apprenticeships of varying durations. One four-year contract from Roman Egypt that apprentices an underage girl to a master weaver shows how detailed terms could be. The owner is to feed and clothe the girl, who is to receive periodic pay raises from the weaver as her skills level up, along with eighteen holidays a year. Sick days are to be tacked onto her term of service, and the weaver is responsible for taxes.[410] The contractual aspect of benefits and obligations seems "distinctly modern"[411] and indicates that a slave on a skills track might have opportunities, bargaining power, and relative social security nearly on a par with or exceeding free but low-skill workers living at a subsistence level. The widely attested success of freedmen might have been one possible motivation for contractual self-sale, as a well-connected owner might be able to obtain training for the slave and market access later as a patron to the new freedman.[412]

.jpg.webp)