On September 19, 1902, a stampede occurred at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing 115 people.

Location

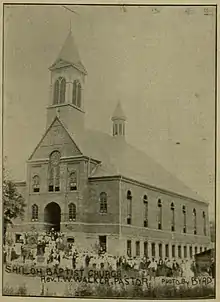

The Shiloh Baptist Church, also known as the Shiloh Negro Baptist Church, located at the corner of 7th Avenue and 19th Street, was at the time the largest black church in Birmingham. The church was crowded with approximately 3,000 people to hear Booker T. Washington address the National Convention of Negro Baptists.[1][2]

Event

According to contemporary accounts published in The New York Times,[2][3] the disaster occurred after Washington concluded his remarks. A convention delegate from Baltimore engaged in a dispute with the choir leader concerning an unoccupied seat. Someone in the choir yelled, "There's a fight!" Mistaking the word "fight" for "fire," the congregation rose en masse and started for the door.[2]

One of the ministers quickly mounted the rostrum and urged the people to keep quiet. He repeated the word "quiet" several times, and motioned to his hearers to be seated. The excited congregation mistook the word "quiet" for a second alarm of fire and again rushed for the door. Men and women crawled over benches and fought their way into the aisles, and those who had fallen were trampled upon. The screams of the women and children added to the horror of the scene. Through mere fright many persons fainted and as they fell to the floor were crushed to death.[2]

The level of the floor of the church is about 15 feet (4.6 m) from the ground, and long steps lead to the sidewalk from the lobby, just outside the main auditorium. Brick walls extend on each side of these steps for six or seven feet (1.8 or 2.1 m), and this proved a veritable death trap. Those who had reached the top of the steps were pushed violently forward and many fell. Before they could move others fell upon them, and in a few moments persons were piled upon each other to a height of ten feet (3.0 m), where they struggled vainly to extricate themselves. This wall of struggling humanity blocked the entrance, and the weight of 1,500 persons in the body of the church was pushed against it. More than twenty persons lying on the steps underneath the heap of bodies died from suffocation.[2]

Two men who were in the rear of the church when the rush began realized the seriousness of the situation and turned in a fire alarm after escaping. The Fire Department answered quickly and the arrival of the wagons served to scatter the crowd which had gathered around the front of the church. A squad of police was also hastened to the church, and with the firemen, finally succeeded in releasing the victims from their positions in the entrance. The dead bodies were quickly removed and the crowd inside finding an outlet poured out. Scores of them lost their footing in their haste and rolled down the long steps to the pavement suffering broken limbs and internal injuries.[2]

Aftermath

In an hour, the church had been practically cleared. Down the aisles and along the outside of the pews there were dead bodies of men and women, and there were still many injured people among the bodies. The work of removing the bodies was begun at once.[2]

The church in which the convention was held is located just on the edge of the South Highlands, a then-fashionable residential section of Birmingham, and physicians living in that part of the town went to the aid of the injured. At least fifteen of those brought out injured died before they could be moved from the ground.[2] Most of the dead were women, and the physicians said in many cases they fainted and died from suffocation. Little or no blood was seen on any of the victims. They were either crushed or were suffocated to death.[2]

Booker T. Washington was quoted after the disaster as saying, "I had just finished delivering my lecture on 'Industry' and the singing had commenced when some woman back of me was heard to scream. A member of the choir yelled, 'Quiet!' which the gallery understood to be 'Fire.' This was repeated and started the stampede. I found on investigation that a Birmingham man had stepped on the toes of a delegate from Baltimore named BALLOU. BALLOU resented it and made a motion as if to draw a gun. This caused the woman to scream."[3]

Local relief efforts were led by banker William R. Pettiford.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Hundred Fifteen Killed, Boston Evening Transcript, September 20, 1902, retrieved January 6, 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Seventy-Eight Negroes Killed in a Mad Panic; Shout of "Fight" Mistaken for an Alarm of "Fire!"", The New York Times, September 19, 1902, archived from the original on September 26, 2015, retrieved January 6, 2015

- 1 2 "Negro Dead Number 115. No White People Killed in the Birmingham Panic.", The New York Times, September 20, 1902, archived from the original on September 26, 2015, retrieved January 6, 2015

- ↑ Death List Unknown, The Evening Bulletin (Maysville, Kentucky) September 23, 1902, page 1, accessed October 12, 2016 at "Death List Unknown, the Evening Bulletin (Maysville, Kentucky) September 23, 1902, page 1 - on Newspapers.com". The Evening Bulletin. 23 September 1902. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2016-10-12.