Shah Mir Dynasty خاندانِ شاہ میٖری | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1339–1561 | |||||||||

Gold coinage of Fath Shah, ruler of the Shah Mir dynasty, circa 1500 CE. Kashmir mint.

| |||||||||

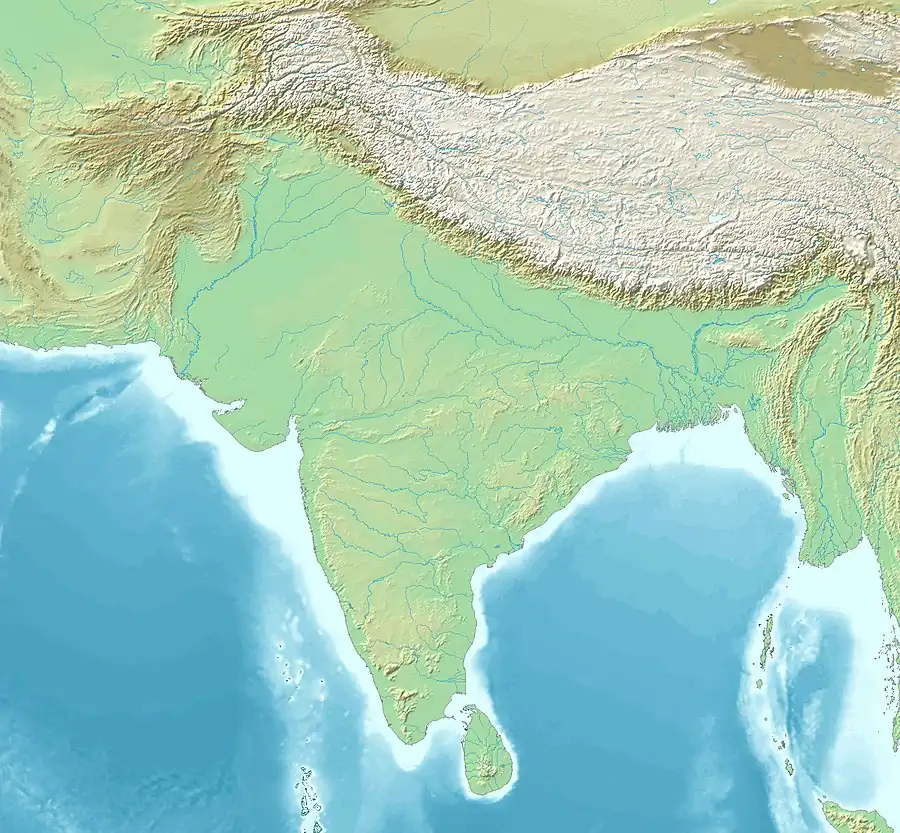

◁ ▷ The Shah Mir Sultanate and other South Asian polities, circa 1400 CE.[1] | |||||||||

Srinagar Rajauri Budhal Swat, Pakistan Gilgit Leh Region of Kashmir and main cities | |||||||||

| Status | Independent State | ||||||||

| Capital | Srinagar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Kashmiri, Persian | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

• 1339–1342 | Shamsu-d-Din Shah | ||||||||

• 1418 – 1419 1420 – 1470 | Zainu'l-Abidin | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1339 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1561 | ||||||||

| Currency | Gold Dinar, Silver Dirham, Copper coin. | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Shah Mir dynasty was a dynasty that ruled the Kashmir Sultanate in the Indian subcontinent.[2] The dynasty is named after its founder, Shah Mir.

Origins

Modern scholarship differ on the origin of Shah Mir. However, most modern historians accept that Shah Mir was from Swat in Dardistan.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Some accounts trace his descent from the rulers of Swāt.[lower-alpha 1][10][11]

Encyclopaedia of Islam (second edition) suggests a possible Turkish origins.[12] Andre Wink puts forward the opinion that Shah Mir was possibly of Afghan, Qarauna Turk, or even Tibetan origin,[13] while A.Q. Rafiqi believes that Shah Mir was a descendant of Turkish or Persian immigrants to Swat.[5]: 311–312 Some scholars state that Shah Mir arrived from the Panjgabbar valley (Panchagahvara),[14] which was populated by Khasa people, and so ascribe a Khasa ethnicity to Shah Mir.[15][16]

Older sources by contemporary Kashmiri historians, such as Jonaraja, state that Shah Mir was the descendant of Partha (Arjuna) of Mahabharata fame. Abu ’l-Fadl Allami, Nizam al-Din and Firishta, also state that Shah Mir traced his descent to Arjuna, the basis of their account being Jonaraja’s Rajatarangini, which Mulla Abd al-Qadir Bada’uni translated into Persian at Akbar’s orders. This seems to be official genealogy of the Sultanate.[5]

History

Shah Mir

A. Q. Rafiqi states:

Shah Mir arrived in Kashmir in 1313 along with his family, during the reign of Suhadeva (1301–1320), whose service he entered. In subsequent years, through his tact and ability Shah Mir rose to prominence and became one of the most important personalities of his time.[5]

Annemarie Schimmel has suggested that Shah Mir belonged to a family from Swat which accompanied the sage Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani and were associated to the Kubrawiya, a Sufi group in Kashmir.[3] He worked to establish Islam in Kashmir and was aided by his descendant rulers, specially Sikandar Butshikan. He reigned for three years and five months from 1339 to 1342 CE. He was the ruler of Kashmir and the founder of the Shah Mir dynasty. He was followed by his two sons who became kings in succession.[17]

Jamshid

._Kashmir_mint._Fixed_date_AH_842_on_reverse.jpg.webp)

Sultan Shamsu'd-Din Shah was succeeded by his elder son Sultan Jamshid who ruled for a year and two months. In 1343 CE, Sultan Jamshid suffered a defeat by his brother who ascended the throne as Sultan Alau'd-Din in 1347 CE.[17]

Alau'd-Din

Sultan Alau'd-Din's two sons became kings in succession, Sultan Shihabu'd-Din and Sultan Qutbu'd-Din.[17]

Shihabu'd-Din

He was the only Shah Mir ruler to keep Hindu courtiers in his court. Prominent among them were Kota Bhat and Udyashri. Ruler of Kashgar (Central Asia) once attacked Kashmir with a large army. Sultan Shihabu’d-din did not have a large number of soldiers to battle against the Kashgar army. But with a small army, he fought and defeated the whole army of Kashgar. After this battle, the regions of Ladakh and Baltistan which were under the rule of Kashgar came under the rule of Shah Miris.Sultan also marched towards Delhi and the army of Feroz Shah Tughlaq opposed him at the banks of River Satluj. Since the battle was motive-less for the Delhi Sultanate peace concluded between them on a condition that all the territories from Sirhind to Kashmir belong to the Shah Mir empire.[19]

Shihabu’d-din was also a great administrator who governed his kingdom with firmness and justice. A town named Shihabu’d-dinpura aka Shadipur was founded by him. He was also called the Lalitaditya of Medieval Kashmir as he erected many mosques and monasteries.

Qutubu'd-Din

He was the next Sultan of Kashmir. The only significance of his rule is that the Sufi saint Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani arrived at Kashmir in his reign. In 1380 C.E. Qutbud’din died and was succeeded by his son Sultan Sikander also known as the Sikander Butshikand.

Sikandar

Sultan Sikandar (1389–1413 CE), was the sixth ruler of the Shah Mir Dynasty.

Barring a successful invasion of Ladakh, Sikandar did not annex any new territory.[20] Iinternal rebellions were ably suppressed.[20][21] A welfare-state was installed — oppressive taxes were abolished, and free schools and hospitals were commissioned.[20] Waqfs were endowed to shrines, mosques were commissioned, numerous Sufi preachers were provided with jagirs and installed in positions of authority, and feasts were regularly held.[22][20][21] Economic condition was decent.[21]

Jonaraja and later Muslim chroniclers accuse Sikandar of terminating Kashmir's longstanding syncretic culture by persecuting Pandits and destroying numerous Hindu shrines; Suhabhat — a Brahman neo-convert and Sikandar's Chief Counsel — is particularly blamed for having instigated him.[21][23] Scholars caution against accepting the allegations at face value and attributing them solely to religious bigotry.[24] His policies, like with the previous Hindu rulers, were likely meant to gain access to the immense wealth controlled by Brahminical institutions;[25][24][26] further, Jonaraja's polemics stemmed, at least in part, from his aversion to the slow disintegration of caste society under Islamic influence.[23][27] However, Sikandar was also the first Kashmiri ruler to convert destroyed temples into Islamic shrines, and such a display of supremacy probably had its origins in religious motivations.[27][28]

Sikandar died in April, 1413 upon which, the eldest son 'Mir' was anointed as the Sultan having adopted the title of Ali Shah.[29]

Ali Shah

He was the seventh ruler of the Shah Mir Dynasty, and reigned between 1413 and 1420.[30] He was defeated by Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin at Thanna with the help of Jasrath Khokhar, a chieftain from Pothohar Plateau. The fate of Ali Shah is uncertain: he may have died in captivity or have been put to death by Khokhar.[30]

Zain-ul-Abidin

Zain-ul-Abidin was the eighth sultan of Kashmir. He was known by his subjects as Bod Shah or Budshah (lit. 'Great King')[31] and ruled from 1418 to 1470.

Zain-ul-Abidin worked hard to establish a fair rule in Kashmir. He called back the Hindus who had left Kashmir during his father reign and allowed building of temples. Jizya was abolished too in his command. From the regulation of commodities to the reviving of old crafts, Abidin did everything for overall development of Kashmir and his subjects. Zain-ul-Abidin is also called as Akbar of Kashmir and Shahjahan of Kashmir on account of religion and development respectively.

Haider Shah

Next Sultan of Kashmir was Haji Khan, who succeeded his father Zain-ul-Abidin and took the title of Haider Khan.[32]

Interruption by Haidar Dughlat

In 1540, the Sultanate was briefly interrupted when Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat, a Chagatai Turco-Mongol military general attacked and occupied Kashmir.[33] Arriving in Kashmir, Haidar installed as sultan the head of the Sayyid faction, Nazuk. In 1546, after Humayun recovered Kabul, Haidar removed Nazuk Shah and struck coins in the name of the Mughal emperor.[34] He died in 1550 after being killed in battle with the Kashmiris. He lies buried in the Gorstan e Shahi in Srinagar.

Architecture

Some of the architectural projects commissioned by the dynasty in Kashmir include:

- Jamia Masjid in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir

- Khanqah-e-Moulah in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir

- Aali Masjid in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir

- Tomb of the Mother of Zain-ul-Abidin in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir

- Amburiq Mosque in Shigar, Gilgit-Baltistan

- Chaqchan Mosque in Khaplu, Gilgit-Baltistan

Tomb of the Mother of Zain-ul-Abidin in Srinagar

Tomb of the Mother of Zain-ul-Abidin in Srinagar.jpg.webp) The courtyard of the Jama Masjid, Srinagar. Hari Parbat is visible in the background.

The courtyard of the Jama Masjid, Srinagar. Hari Parbat is visible in the background. The Khanqah on the banks of Jhelum

The Khanqah on the banks of Jhelum A view of Ziyarat Naqshband Sahab from its yard.

A view of Ziyarat Naqshband Sahab from its yard.

Reign and successions

| No. | Titular Name | Birth Name | Reign |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shamsu'd-Dīn Shāh شَمس اُلدِین شَاہ | Shāh Mīr شَاہ مِیر | 1339 – 1342 |

| 2 | Jamshīd Shāh جَمشید شَاہ | Jamshīd جَمشید | 1342 – 1342 |

| 3 | Alāu'd-Dīn Shāh عَلاؤ اُلدِین شَاہ | Alī Shēr عَلی شیر | 1343 – 1354 |

| 4 | Shihābu'd-Dīn Shāh شِہاب اُلدِین شَاہ | Shīrashāmak شِیراشَامَک | 1354 – 1373 |

| 5 | Qutbu'd-Dīn Shāh قُتب اُلدِین شَاہ | Hindāl حِندَال |

1373 – 1389 |

| 6 | Sikandar Shāh سِکَندَر شَاہ | Shingara شِنگَرَہ | 1389 – 1412 |

| 7 | Alī Shāh عَلی شَاہ | Mīr Khān مِیر خَان | 1412 – 1418 |

| 8 | Zainu'l-'Ābidīn زین اُلعَابِدِین | Shāhī Khān شَاہی خَان | 1418 – 1419 |

| 9 | Alī Shāh عَلی شَاہ | Mīr Khān مِیر خَان | 1419 – 1420 |

| 10 | Zainu'l-'Ābidīn زین اُلعَابِدِین | Shāhī Khān شَاہی خَان | 1420 – 12 May 1470 |

| 11 | Haider Shāh حیدِر شَاہ | Hāji Khān حَاجِی خَان |

12 May 1470 – 13 April 1472 |

| 12 | Hasan Shāh حَسَن شَاہ | Hasan Khān حَسَن خَان |

13 April 1472 – 19 April 1484 |

| 13 | Muhammad Shāh مُحَمَد شَاہ | Muhammad Khān مُحَمَد خَان | 19 April 1484 – 14 October 1486 |

| 14 | Fatēh Shāh فَتح شَاہ | Fatēh Khān فَتح خَان | 14 October 1486 – July 1493 |

| 15 | Muhammad Shāh مُحَمَد شَاہ | Muhammad Khān مُحَمَد خَان | July 1493 – 1505 |

| 16 | Fatēh Shāh فَتح شَاہ | Fatēh Khān فَتح خَان | 1505 – 1514 |

| 17 | Muhammad Shāh مُحَمَد شَاہ | Muhammad Khān مُحَمَد خَان | 1514 – September 1515 |

| 18 | Fatēh Shāh فَتح شَاہ | Fatēh Khān فَتح خَان | September 1515 – August 1517 |

| 19 | Muhammad Shāh مُحَمَد شَاہ | Muhammad Khān مُحَمَد خَان | August 1517 – January 1528 |

| 20 | Ibrahīm Shāh اِبرَاہِیم شَاہ | Ibrahīm Khān اِبرَاہِیم خَان |

January 1528 – April 1528 |

| 21 | Nāzuk Shāh نَازُک شَاہ | Nādir Shāh نَادِر شَاہ |

April 1528 – June 1530 |

| 22 | Muhammad Shāh مُحَمَد شَاہ | Muhammad Khān مُحَمَد خَان | June 1530 – July 1537 |

| 23 | Shamsu'd-Dīn Shāh II شَمس اُلدِین شَاہ دوم | Shamsu'd-Dīn شَمس اُلدِین |

July 1537 – 1540 |

| 24 | Ismaīl Shāh اِسمَاعِیل شَاہ | Ismaīl Khān اِسمَاعِیل خَان |

1540 – December 1540 |

| 25 | Nāzuk Shāh نَازُک شَاہ | Nādir Shāh نَادِر شَاہ |

December 1540 – December 1552 |

| 26 | Ibrahīm Shāh اِبرَاہِیم شَاہ | Ibrahīm Khān اِبرَاہِیم خَان |

December 1552 – 1555 |

| 27 | Ismaīl Shāh اِسمَاعِیل شَاہ | Ismaīl Khān اِسمَاعِیل خَان |

1555 – 1557 |

| 28 | Habīb Shāh حَبِیب شَاہ | Habīb Khān حَبِیب خَان |

1557 – 1561 |

Note: Muhammad Shah had five separate reigns from 1484 to 1537.[36]

See also

| History of Kashmir |

|---|

|

Notes

References

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (d). ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ Sharma, R. S. (1992), A Comprehensive History of India, Orient Longmans, p. 628, ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1

- 1 2 Schimmel, Annemarie (1980). Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. BRILL. p. 44. ISBN 90-04-06117-7. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ↑ Wani, Muhammad Ashraf; Wani, Aman Ashraf (22 February 2023). The Making of Early Kashmir: Intercultural Networks and Identity Formation. Taylor & Francis. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-000-83655-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Baloch, N. A.; Rafiq, A. Q. (1998). "The regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan and Kashmir: the historical, social and economic setting". History of Civilizations of Central Asia (PDF). Vol. IV. Unesco. pp. 293–318. ISBN 923103467-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Malik, Jamal (6 April 2020). Islam in South Asia: Revised, Enlarged and Updated Second Edition. BRILL. p. 157. ISBN 978-90-04-42271-1.

- ↑ Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1970). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- ↑ Markovits, Claude (24 September 2004). A History of Modern India, 1480-1950. Anthem Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2.

- ↑ Gull, Surayia (2003), Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani And Kubraviya Sufi Order In Kashmir, Kanikshka Publishers, Distributors, p. 3, ISBN 978-81-7391-581-9

- ↑ Bhatt, Saligram (2008). Kashmiri Scholars Contribution to Knowledge and World Peace: Proceedings of National Seminar by Kashmir Education Culture & Science Society (K.E.C.S.S.), New Delhi. APH Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 978-81-313-0402-0.

- ↑ Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Kashmir Under the Sultans. Aakar Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7.

- ↑ Lewis; Pellat; E.J. van Donzel, ed. (28 May 1998). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume IV (Iran-Kha). Brill. p. 708. ISBN 978-90-04-05745-6. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

But her authority was challenged by Shah Mir, a soldier of fortune, who was most probably of Turkish origin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ↑ Wink, André (2004), Indo-Islamic society: 14th - 15th centuries, BRILL, p. 140, ISBN 90-04-13561-8,

The first Muslim dynasty of Kashmir was founded in 1324 by Shah Mìrzà, who was probably an Afghan warrior from Swat or a Qarauna Turk, possibly even a Tibetan ...

- ↑ Sharma, R. S. (1992), A Comprehensive History of India, Orient Longmans, p. 628, ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1,

Jonaraja records two events of Suhadeva's reign (1301-20), which were of far-reaching importance and virtually changed the course of the history of Kashmir. The first was the arrival of Shah Mir in 1313. He was a Muslim condottiere from the border of Panchagahvara, an area situated to the south of the Divasar pargana in the valley of river Ans, a tributary of the Chenab.

- ↑ Wani, Nizam-ud-Din (1987), Muslim rule in Kashmir, 1554 A.D. to 1586 A.D., Jay Kay Book House, p. 29,

Shamir was a Khasa by birth and descended from the chiefs of Panchagahvara.

- ↑ Zutshi, N. K. (1976), Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin of Kashmir: an age of enlightenment, Nupur Prakashan, p. 7,

"This area in which Panchagahvara was situated is mentioned as having been the place of habitation of the Khasa tribe. Shah Mir was, therefore, a Khasa by birth. This conclusion is further strengthened by references to the part of the Khasas increasingly played in the politics of Kashmir with which their connections became intimate after the occupation of Kashmir.

- 1 2 3 Baharistan-i-Shahi – Chapter 3 – EARLY SHAHMIRS

- ↑ Local notice

- ↑ Nath, R. (2003). "Qutb Shahi". Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t070476. ISBN 9781884446054.

- 1 2 3 4 Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Kashmīr Under the Sultāns. Aakar Books. pp. 59–95. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Slaje, Walter (2014). Kingship in Kaśmīr (AD 1148‒1459) From the Pen of Jonarāja, Court Paṇḍit to Sulṭān Zayn al-'Ābidīn. Studia Indologica Universitatis Halensis - 7. Germany. ISBN 978-3869770888.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2003). "Contested Identities in the Kashmir Valley". Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. Permanent Black. ISBN 978-81-7824-060-2.

- 1 2 Slaje, Walter (19 August 2019). "Buddhism and Islam in Kashmir as Represented by Rājataraṅgiṇī Authors". Encountering Buddhism and Islam in Premodern Central and South Asia. De Gruyter. pp. 128–160. doi:10.1515/9783110631685-006. ISBN 978-3-11-063168-5. S2CID 204477165.

- 1 2 Obrock, Luther James (2015). Translation and History: The Development of a Kashmiri Textual Tradition from ca. 1000–1500 (Thesis). UC Berkeley.

- ↑ Zutshi, Chitralekha (24 October 2017). "This book claims to expose the myths behind Kashmir's history. It exposes its own biases instead". Scroll.in. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Salomon, Richard; Slaje, Walter (2016). "Review of Kingship in Kaśmīr (AD1148–1459). From the Pen of Jonarāja, Court Paṇḍit to Sulṭān Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn. Critically Edited by Walter Slaje with an Annotated Translation, Indexes and Maps. [Studia Indologica Universitatis Halensis 7], SlajeWalter". Indo-Iranian Journal. 59 (4): 393–401. doi:10.1163/15728536-05903009. ISSN 0019-7246. JSTOR 26546259.

- 1 2 Slaje, Walter (2019). "What Does it Mean to Smash an Idol? Iconoclasm in Medieval Kashmir as Reflected by Contemporaneous Sanskrit Sources". Brahma's Curse : Facets of Political and Social Violence in Premodern Kashmir. Studia Indologica Universitatis Halensis - 13. pp. 30–40. ISBN 978-3-86977-199-1.

- ↑ Hamadani, Hakim Sameer (2021). The Syncretic Traditions of Islamic Religious Architecture of Kashmir (Early 14th −18th Century). Routledge. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9781032189611.

While medieval Muslim hagiographic and historical accounts may have exaggerated Sikander's destruction of non-Muslim religious sites in a classical representation of religious piety, the tendency of some writers in the twentieth century CE to shield the Sultan from these iconoclastic activities is not historically correct, especially given the evidence from the period coming from writers of different religious backgrounds.

- ↑ Slaje, Walter (2014). Kingship in Kaśmīr (AD 1148‒1459) From the Pen of Jonarāja, Court Paṇḍit to Sulṭān Zayn al-'Ābidīn. Studia Indologica Universitatis Halensis - 7. Germany. ISBN 978-3869770888.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Hasan, Mohibbul (2005) [1959]. Kashmir Under the Sultans (Reprinted ed.). Delhi: Aakar Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ↑ Hasan, Mohibbul (2005) [1959]. Kashmir Under the Sultans (Reprinted ed.). Delhi: Aakar Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ↑ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai:Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, p.383

- ↑ Shahzad Bashir, Messianic Hopes and Mystical Visions: The Nurbakhshiya Between Medieval And Modern Islam (2003), p. 236.

- ↑ Stan Goron and J.P. Goenka: The Coins of the Indian Sultanates, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2001, pp. 463–464.

- ↑ Hasan, Mohibbul (2005) [1959]. Kashmir Under the Sultans (Reprinted ed.). Delhi: Aakar Books. p. 325. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Sultans of Kashmir".