The Scotia Mine began operating in 1962 and was a subsidiary of the Blue Diamond Coal Company. The mine was located in the Oven Fork Community of Letcher County, about fourteen miles northeast of the town of Cumberland (Harlan County, Kentucky).[1]

The Scotia Mine was originally opened into the Imboden coalbed.[2] In 1975, an additional opening in the form of a concrete lined 13+1⁄2 foot diameter shaft, 376 feet deep. The lining of the shaft was completed July 21, 1975, and work was begun to install an automatic elevator. On March 9, 1976, the construction had not yet been completed and the shaft was being used only as an intake air opening.[2] Of 310 employees, 275 worked underground on two coal producing shifts and one maintenance shift per day, 5 days a week. Approximately 2,500 tons of coal were produced daily on six active sections, consisting of five continuous mining sections and one conventional mining section.[2]

The last federal inspection of the Scotia Mine was completed on February 27, 1976. On March 8, 1976, on the evening shift, a Federal Coal Mine Inspector conducted a Health and Safety Technical Inspection.[2]

Scotia Mine Disaster of 1976

On March 9, 1976, at approximately 11:45 a.m., an explosion caused by coal dust and gasses rocked the Scotia Mine. Two days later, a twin explosion occurred. The first explosion killed fifteen miners; the second killed eleven. Investigators believed that both explosions were caused by methane gasses ignited by a spark in a battery-powered locomotive or another electric device. A lack of ventilation also contributed to the accidents.[1][3]

The explosions at Scotia led to the passage of the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977.[4] This law strengthened the previously passed 1969 act.[5] The 1977 law also moved the Mine Safety and Health Administration from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Labor.[6]

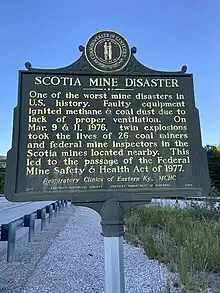

Historical Marker #2314 in Letcher County notes the tragic mine explosions that occurred at Scotia Mine in 1976. The accidents are noted as being one of the worst mine disasters in U.S. history.

Lives lost in Scotia Mine Disaster[7][8]

- Glenn Barker, 29 years-old

- Dennis Boggs, 27 years-old

- Everett Scott Combs, 29 years-old

- Virgil Coots, 24 years-old

- Don Creech, 30 years-old

- Larry David McKnight, 28 years-old

- Earl Galloway, 44 years-old

- David Gibbs, 30 years-old

- Robert Griffith, 24 years-old

- John Hackworth, 29 years-old

- J. B. Holbrook, 43 years-old

- Kenneth B. Kiser, 45 years-old

- Roy McKnight, 31 years-old

- Lawrence Peavy, 25 years-old

- Carl Polly, 47 years-old

- Richard M. Sammons, 55 years-old

- Tommy Ray Scott, 24 years-old

- Ivan Gail Sparkman, 34 years-old

- James Sturgill, 46 years-old

- Jimmy W. Sturgill, 20 years-old

- Monroe Sturgill, 40 years-old

- Kenneth Turner, 25 years-old

- Willie D. Turner, 25 years-old

- Grover Tussey, 45 years-old

- Denver Widner, 31 years-old

- James Williams, 23 years-old

Lawsuit

In 1977, the widows of the miners who died in the mine disaster (the Scotia widows) sued Blue Diamond Coal Company of Knoxville, Tennessee. The United States District Court judge Howard David Hermansdorfer for the Eastern District of Kentucky ruled that Blue Diamond Coal Company was exempt from tort liability under Kentucky's Workmen's Compensation Act and dismissed the lawsuit.[9] The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held that, under Kentucky's Workmen's Compensation Act a parent corporation is not immune from tort liability to its subsidiary employees for its own, independent acts of negligence.[10]

Further reading

References

- 1 2 Talbott, Tim. "Scotia Mine Disaster". ExploreKYHistory. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- 1 2 3 4 "Scotia Mine Explosion". usminedisasters.miningquiz.com. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ Sinclair, Ward; Bishop, Bill (1980-03-09). "Justice Moves Slowly in Mine Disaster". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ "1977 – Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) created | Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA)". www.msha.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ "1969 – Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act passed | Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA)". www.msha.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ Time, Ben A. Franklin Special to The New York (1976-07-29). "House Votes Mine Safety Shift To Dept. of Labor From Interior (Published 1976)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ Times, Wayne King Special to The New York (1976-11-20). "Bodies of 11, Entombed in Mine 253 Days, Recovered (Published 1976)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ "Miners Killed in the Scotia Mine Explosions". usminedisasters.miningquiz.com. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ Boggs v. Blue Diamond Coal Co., 590 F.2d 655, 657 (6th Cir. 1979).

- ↑ Boggs v. Blue Diamond Coal Co., 590 F.2d 655, 663 (6th Cir. 1979).

- ↑ J. K. Richmond, G. C. Price, M. J. Sapko and E. M. Kawenski (2006-05-12). "Historical Summary of Coal Mine Explosions in the United States, 1959-81 (Bureau of Mines Information Circular/1983)" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cook, Colleen Ryckert. (2011). Kentucky : past and present (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Central. ISBN 978-1-4358-9482-2. OCLC 502304593.

- ↑ Stern, Gerald M., 1937- (2008). The Scotia widows : inside their lawsuit against big daddy coal. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6764-0. OCLC 189699502.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)