| Sammed Shikharji | |

|---|---|

Jain Temples at Shikarji | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Jainism |

| Deity | Tirthankar |

| Festivals | Paryushana |

| Location | |

| Location | Giridih, Jharkhand, India |

Location within Jharkhand  Shikharji (India) | |

| Geographic coordinates | 23°57′40″N 86°8′13.5″E / 23.96111°N 86.137083°E |

| Elevation | 1,365 m (4,478 ft) |

Shikharji (Śikharjī), also known as Sammed or Sammet Shikharji, is one of the Holiest pilgrimage sites for Jains, in Giridih district, Jharkhand. It is located on Parasnath hill, the highest mountain in the state of Jharkhand.[1] It is the most important Jain Tirtha (pilgrimage site), for it is the place where twenty of the twenty-four Jain tirthankaras (supreme preachers of Dharma) along with many other monks attained Moksha. It is one of the five principal pilgrimage destinations along with Girnar, Pawapuri, Champapuri, Dilwara, Palitana and Ashtapad Kailash.

Etymology

Shikharji means the "venerable peak". The site is also called Sammed Śikhar "peak of concentration" because it is a place where twenty of twenty-four Tirthankaras attained Moksha through meditation.[2][3][4] The word "Parasnath" is derived from Lord Parshvanatha, the twenty-third Jain Tirthankara, who was one of those who attained Moksha at the site in 772 BCE.[5][6][7][8]

Geography

Shikarji is located in an inland part of rural east India. It lies on NH-2, the Delhi-Kolkata highway in a section called the Grand Trunk road Shikharji rises to 4,480 feet (1,370 m) making it the highest mountain in Jharkhand state.[4]

Jain tradition

Shikharji is the place where twenty of the twenty-four Jain tirthankaras including Parshvanatha along with many other monks attained Moksha.[6][3][9][10] This pilgrimage site is considered the most important Jain Tirtha by both Digambara and Śvētāmbara.[11][12] Shikharji along with Ashtapad, Girnar, Dilwara Temples of Mount Abu and Shatrunjaya are known as Śvētāmbara Pancha Tirth (five principal pilgrimage shrine).[13]

History

Archaeological evidences indicate the presence of Jains going back to at least 1500 BCE. The earliest literary reference to Shikharji as a tirth (place of pilgrimage) is found in the Jñātṛdhārmakātha, one of the twelve core texts of Jainism compiled in 6th century BCE by chief disciple of Mahavira. Shikharji is also mentioned in the Pārśvanāthacarita, a twelfth-century biography of Pārśva. A 13th century CE palm-leaf manuscript of Kalpa Sūtra and Kalakacaryakatha has an image of a scene of Parshavanatha's nirvana at Shikharji.[14]

Modern history records show that Shikharji Hill is regarded as the place of worship of the Jain community. Vastupala, prime minister during the reign of king Vīradhavala and Vīsaladeva of Vaghela dynasty, constructed a Jain temple housing 20 idols of Tirthankaras.[15] The temple also housed images of his ancestors and Samavasarana.[16] During the regime of Mughal's rule in India, Emperor Akbar in the year 1583 had passed an firman (official order) granting the management of Shikharji Hill to the Jain community to prevent the slaughter of animals in the vicinity.[17][18] Seth Hiranand Mukim, personal jeweller of Mughal Emperor Jahangir, lead a party from Agra to Shikharji for Jain pilgrimage.[19] In 2019, the Government of Delhi included Sammed Shikharji under Mukhyamantri Tirth Yatra Yojana.[20]

Approach

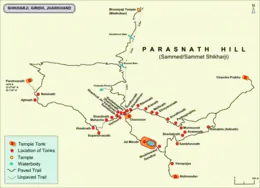

The pilgrimage of Shikharji starts with a Palganj on Giridih road. Palganj has a small shrine dedicated to Parshvanatha. Then, offerings are made to temples at Madhuban on the base of Parasnath hill.[21] Madhuban has many dharamshalas and bhojnalayas for pilgrims.[22]

The section from Gandharva Nala stream to the summit is the most sacred to Jains.[1] The pilgrimage is made on foot or by a litter or doli carried by a doliwallah along a concrete paved track.[23] A trek of 16.777 miles (27.000 km) is covered while performing Parikrama of Shikharji.[18] However, the complete parikrama of Madhuban to Shikharji and back is 57 kilometres (35 mi).[24]

Temples

Shikharji is considered as the most important pilgrimage centre by both the Digambara and Śvētāmbara sects of Jainism and the jurisdiction of the main temples is shared by both sects.[11]

The current structure of temples at Shikharji was re-built by Jagat Seth in 1768 CE.[25] However, the idol itself is very old. The Sanskrit inscription at the foot of the image is dated 1678 CE. One of the shrines dates back to the 14th century.[22] Several Śvētāmbara temples were constructed in 20th century.[26] Pilgrims offer rice, sandal, dhupa, flower, fruits and diya.[25]

At the base of Shikharji is a temple to Bhomiyaji (Taleti). On the walls of the Jain temple at the village of Madhuban, there is a mural painting depicting all the temples on Parasnath Hill. Śvētāmbara Bhaktamara temple, established by Acharya Ramchandrasuri, is the first temple to house a Bhaktamara Stotra yantra.[27]

A large Digambara Jain temple depicting Nandishwar Dweep is at the base of the hill.[28] The Nichli temple, built by a Calcutta merchant in 18th century, is noteworthy for its architecture. The temple features arched gateways and carvings of Tirthankaras on the temple wall.[29]

Tonks

.jpg.webp)

There are 31 tonks each enshrines footprints, in black or white marble, of each Tirthankara. Since, these temple does not have images these tonks are worshipped by both Digambara and Śvētāmbara.[26]

- Parshvanatha tonk

The hilltop where Parshvanatha attained moksha is called 'suvarṇabhadra kūța' and is considered the most sacred hilltop on Shikharji. The Parshvanatha tonk is constructed at this summit.[30][31][26] The chatra distinguishes Parshvanatha footprint from footprints of other 23 Tirthankaras which does not have chatra and are indistinguishable.[32] The temple consists of two floors. The top floor has a tonk with no footprints of Parshvanatha, and lower floor enshrines a saffron coloured replica of the face of Parasnath built into a wall. Devotees make offerings of uncooked rice and sweets here.[33]

The tonks along the track are as follows:[26][34]

- Gautam Ganadhara Swami

- Kunthunatha

- Rishabha

- Chandraprabha

- Naminatha

- Aranatha

- Māllīnātha

- Shreyanasanatha

- Pushpadanta

- Padmaprabha

- Munisuvratnath

- Chandraprabha

- Rishabha

- Anantanatha

- Shitalanatha

- Sambhavanatha

- Vasupujya

- Abhinandananatha

- Ganadhara

- Jal Mandir

- Dharmanatha

- Mahavira

- Varishen

- Sumatinatha

- Shantinatha

- Mahavira

- Suparshvanatha

- Vimalanatha

- Ajitanatha

- Neminatha

- Parshvanatha

Fair

Sammed Shikhar festival is annual fair organised here that draws a huge number of devotees.[35]

Replicas

The representation of Sammeta-Shikharji is a popular theme in Jain shrines.[15]

On 13 August 2012, the world's first to-scale complete replication of Shikharji was opened in Siddhachalam in New Jersey over 120 acres of hilly terrain called Shikharji at Siddhachalam, it has become an important place of pilgrimage for the Jain diaspora.[36] There is a small scale replica of Shikharji at Dādābadī, Mehrauli. Ranakpur Jain temple has a depiction of Shikharji.[37] Shitalnath temple in Patan, Gujarat has a wooden plaque with carving of Shikharji.[13]

Transport

The nearest railway station is Parasnath Station which is situated in Isri Bazar, Dumri, Jharkhand. It is around 25 km from Madhuban, at the base of Shikharji. Parasnath station is situated on Grand Chord, which is part of Howrah-Gaya-Delhi line and Howrah-Allahabad-Mumbai line. Many long-distance trains halt at Parasnath Station. Daily connectivities to Mumbai, Delhi, Jaipur, Ajmer, Kolkata, Patna, Allahbad, Kanpur, Jammutawi, Amritsar, Kalka etc. are available. Even 12301-12302 Howrah Rajdhani Express via Gaya Junction has a halt on Parasnath station which run 6 days a week.

By Airway;

The Nearest airport is Deoghar Airport in Deoghar Dist, known as Baidyanath dham which is famous for Hindu pilgrimage sites, part of 12 jyotirling for Lord Shiva. The airport is 107 km away from Shikharji and a 3-hour drive.

Another airport is Kazi Nazrul Islam Airport, Durgapur (RDP) West Bengal and a 4-hour drive from the airport. Durgapur has direct flights from Kolkata and Delhi

Birsa Munda Airport, Ranchi (IXR), Jharkhand is also around 180 km (Approximately 4.5 hours), and the drive to Shikhar Ji is quite smooth. Direct flights are available from Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Bhubaneswar,Chennai, Delhi, Deoghar,Goa–Mopa,Hyderabad, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mangalore,Mumbai, Patna and Pune.

Shikharji movement

Save Shikharji was a protest movement by Jain sects against the state's alleged development plans for Shikharji. Jains opposed the plans of the state government to improve the infrastructure on the site of the hill in order to boost tourism as alleged attempts to commercialize the Shikharji hill.[38] The movement demanded that Shikharji Hill be declared officially a place of worship by the Government of Jharkhand.[18] On 26 October 2018, the Government of Jharkhand issued an official memorandum declaring the Shikharji hill as a 'place of worship'.

In December 2022, Jains carried out massive protests and a one-day nationwide strike against the rule by the Government of Jharkhand to tag Shikharji as a place of tourism. [39] Jharkhand government's decision to declare 'sacred' Shri Sammed Shikharji a tourist place and incidents of allegedly desecrating the sacred Shetrunjaya Hills in Gujarat's Bhavnagar district have triggered anger among lakhs of people belonging to the Jain community. A 72-year-old Jain monk who was on a fast against the Jharkhand government's decision died Tuesday in Jaipur, according to a community leader. Police said after participating in a peace march in Jaipur against the decision, Sugyeysagar Maharaj sat on the fast at Sanghiji temple in Sanganer area of the city.

In January 2023, the Central government halted all tourism development activities on Parasnath Hills.[40]

Gallery

Jal Mandir

Jal Mandir Pushpadanta idol inside Pushpadanta Jinalaya

Pushpadanta idol inside Pushpadanta Jinalaya Gautam Swami Temple at Madhuban

Gautam Swami Temple at Madhuban Mahavir Tonk

Mahavir Tonk

See also

References

Citation

- 1 2 Shukla & Kulshreshtha 2019, p. 103.

- ↑ Burgess & Spiers 1910, p. 44.

- 1 2 Cort 2010, pp. 130–133.

- 1 2 Jharkhand Tourism.

- ↑ Balfour 1885, p. 141.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ Sangave 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ University of Calcutta 1845, p. 256.

- ↑ Titze & Bruhn 1998, p. 202.

- ↑ Shah 2004, p. 191.

- 1 2 Dundas 2002, p. 221.

- ↑ Dalal 2010, p. 718.

- 1 2 Cort 2010, p. 132.

- ↑ Eastman 1943, p. 95.

- 1 2 Shah 1987, p. 98.

- ↑ Granoff & Shinohara 2003, p. 320.

- ↑ Jain 2012, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Jain 2018.

- ↑ Gopal 2019, p. 165.

- ↑ Outlook 2019.

- ↑ Bengal Printing Company 1868, p. 23.

- 1 2 Cooke 1906, p. 350.

- ↑ Shrinivasa 2018.

- ↑ Bengal Printing Company 1868, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 Bengal Printing Company 1868, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 Wiley 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Gough 2021, pp. 209–2010.

- ↑ Cort 2010, p. 85.

- ↑ Bradley-Birt 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ Jain 2019, p. 4.

- ↑ Cooke 1906, p. 351.

- ↑ Bengal Printing Company 1868, p. 25.

- ↑ JTDCL.

- ↑ "A study of Jain sacred place - Sammed Shikharji: Religious significance to its physical form". Vebuka.com. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ↑ Ministry of Tourism.

- ↑ Richardson 2014, p. 174.

- ↑ Shah 1987, p. 340.

- ↑ TNN.

- ↑ Abraham 2018.

- ↑ "After Jain Community Slams Tourism Tag For Shrine, Centre's Big Move". NDTV.com. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

Sources

Books

- Balfour, Edward (1885), The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, vol. 3rd volume (Commercial, Industrial and Scientific, Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures ed.), B. Quaritch, retrieved 2 October 2017

- Burgess, James; Spiers, R. Phené (1910). History of Indian and Eastern architecture (PDF). London: John Murray (publishing house).

- Bengal Printing Company (1868). Parasnath, its history and advantages as a civil sanatarium. Bengal Printing Company.

- Bradley-Birt, Francis Bradley (1998) [1903], Chota Nagpur, a Little-known Province of the Empire, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 9788120612877

- Cooke, Clement Kinloch (1906). Empire Review. Vol. 11. Macmillan Publishers.

- Cort, John E. (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1.

- Dalal, Roshen (2010) [2006], The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992]. The Jains (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5.

- Granoff, Phyllis; Shinohara, Koichi (2003). Pilgrims, Patrons, and Place: Localizing Sanctity in Asian Religions. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774810395.

- Gopal, Surendra (2019). Jains in India: Historical Essays. Routledge. ISBN 9780429537370.

- Gough, Ellen (11 October 2021). Making a Mantra: Tantric Ritual and Renunciation on the Jain Path to Liberation. New Studies in Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226767062.

- Hachette India (25 October 2013). Indiapedia: The All-India Factfinder. Hachette India. ISBN 978-93-5009-766-3.

- Richardson, E. Allen (2014), Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West, McFarland, ISBN 9780786459735

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- Shukla, U. N.; Kulshreshtha, Sharad Kumar (2019), Emerging Trends in Indian Tourism and Hospitality: Transformation and Innovation, Copal Publishing Group, ISBN 9789383419760

- Titze, Kurt; Bruhn, Klaus (1998). Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence (2 ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1534-3.

- University of Calcutta (1845). Calcutta Review. Vol. 3. University of Calcutta.

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009), The A to Z of Jainism, vol. 38, The Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6337-8

Web

- Eastman, Alvan C. (1943). "Iranian Influences in Śvetāmbara Jaina Painting in the Early Western Indian Style". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 63 (2): 93–113. doi:10.2307/594116. JSTOR 594116. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Jain, Shalin (2012). "Interaction of the 'Lords': The Jain Community and the Mughal Royalty under Akbar". Social Scientist. 40 (3): 33–57. JSTOR 41633801. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Jain, Vijay K. (2019), Ācārya Kundakunda's Niyamasāra – The Essence of Soul-adoration, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788193272633,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Abraham, Bobins (26 October 2018). "Huge Relief For Jain Community As Jharkhand Accepts Plea To Save The Holy Shikharji Hill". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Jain, Bhavika (14 October 2018). "Jains protest plan to convert sacred hill into tourist centre". The Times of India.

- Shrinivasa, M. (9 February 2018). "Expert team of doli lifters carries devotees to the top". The Times of India.

- "Parasnath". Jharkhand Tourism.

- TNN (11 January 2016). "Plot identified for helipad atop Parasnath Hill". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Jain community thanks Delhi CM for including Sammed Shikharji under Mukhyamantri Tirth Yatra Yojana". Outlook. 16 October 2019.

- "Tourism survey in the State of Jharkhand" (PDF). Ministry of Tourism (India).

- "Johar Jharkhand" (PDF). Department of Tourism Government of Jharkhand. Jharkhand Tourism Development Corporation Limited.

External links

- Tourist Places in Giridih (Official Website)

Parasnath Hills travel guide from Wikivoyage

Parasnath Hills travel guide from Wikivoyage