| Salteropterus Temporal range: Late Silurian, | |

|---|---|

| |

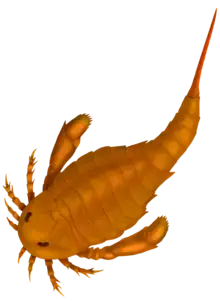

| Illustration of the specimen BGS GSM Zf-2864 of S. abbreviatus, which preserves the telson and the tenth to twelfth abdominal segments. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Pterygotioidea |

| Family: | †Slimonidae |

| Genus: | †Salteropterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1951[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Salteropterus abbreviatus Salter, 1859[2] | |

| Species | |

Salteropterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Salteropterus have been discovered in deposits of Late Silurian age in Britain. Classified as part of the family Slimonidae, the genus contains one known valid species, S. abbreviatus, which is known from fossils discovered in Herefordshire, England, and a dubious species, S. longilabium, with fossils discovered in Leintwardine, also in Herefordshire. The generic name honours John William Salter, who originally described S. abbreviatus as a species of Eurypterus in 1859.

Salteropterus is assumed to have been quite similar to its close relative Slimonia, but the fragmentary nature of the fossil remains of Salteropterus make direct comparisons difficult. Salteropterus does however preserve a highly distinctive telson (the posteriormost division of the body) unlike any other in the Eurypterida. Beginning with an expanded and flattened section, like that of Slimonia, the telson ends in a long stem that culminates in a tri-lobed structure at its end. Though the exact function remains unknown, this structure might have been used for additional balancing alongside the flattened part preceding it.

Description

Salteropterus is a rare eurypterid, and is known mainly from the fossilised remains of its metastoma (a large plate that is part of the abdomen) and telson (the posteriormost division of the body). The telson is the most distinctive feature of the genus, in that it has a trigonal (triangular) shape with serrated posterior edges. The flattened trigonal part of the telson ends in an elongated stem that far exceeds the rest of the telson in length. Unlike in the closely related Slimonia, where a similar (but significantly shorter) structure exists, the rod of Salteropterus does not end in a spike. Rather, it ends in a flattened and tri-lobed organ. Though body parts beyond the telson are fragmentary in known specimens of Salteropterus, the known abdominal segments and their tergites (the upper plates that make up the segments) are long like those of Slimonia, which Salteropterus likely resembled in general.[1]

The long stem- or rod-like structure of the telson is ornamented on each side with tubercles (knobs), arranged in pairs, that gradually get flatter. The tri-lobed structure, sometimes dubbed the "post-telson" (though this structure was part of the telson), on the end of the stem is unique to Salteropterus.[4] The central lobe is larger than the other two, extending beyond them and having a ventral position. It is possible that this tri-lobed structure had the function of additional balancing in combination with the large flattened part before it.[1]

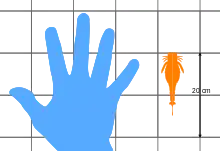

The specimen BGS GSM Zf-2864 is the most complete known specimen of Salteropterus, preserving the telson along with the tenth to twelfth abdominal segments. In this specimen, the entire telson measures 3.1 cm (1.2 in) in length and 1.3 cm (0.5 in) in width. Larger specimens are known however, with a specimen described by Henry Woodward in 1864 measuring 1.6 cm (0.6 in) in width.[1] A small part of a tergite (specimen BGS GSM Zf-2866) preserves large and raised triangular mucrones (median spines on the outer surface). The largest such mucrone (0.4 cm, 0.15 in, in width) suggests that Salteropterus could grow much larger than the known small specimens would suggest.[1]

History of research

Salteropterus abbreviatus was named as a species of Eurypterus by John William Salter in 1859, though the specimen used was not nearly complete enough to reveal the unique features of Salteropterus known today. Salter considered the species to be "thoroughly distinct", yet similar to Eurypterus acuminatus (today classified as Herefordopterus), with a telson that was as if the one of E. acuminatus had been abbreviated, hence the name of the taxon.[2] More complete specimens would be discovered in Perton in Herefordshire, England in the late 1800s and early 1900s.[1] The fossil remains known of Salteropterus are all fragmentary, similar to other eurypterid fossils recovered from Perton. Though the Perton fossils are almost universally fragmentary, they preserve unusually delicate details, for example individual facets on the eyes of a specimen of Hughmilleria and bristles of epicoxites (a process on the end of the toothed part of the coxae).[1]

Fossilised remains of eurypterids have been known from Perton since 1869, when Rev. Peter Bellinger Brodie notified the Geological Society of London about fossil Eurypterus and Pterygotus he had discovered in the region. The specimens collected were examined by Henry Woodward, who determined that they consisted of Pterygotus banksii along with various species of Eurypterus, including E. acuminatus, E. pygmaeus and E. abbreviatus. Eurypterus abbreviatus was reclassified under a genus of its own, Salteropterus, in 1951 by Erik N. Kjellesvig-Waering following the discovery and description of a more complete telson (specimen number BGS GSM Zf-2864) discovered by Roy Woodhouse Pocock and A. J. Butler in the quarry of Perton in 1939. Preserving an elongate telson that had been unknown to Woodward, the specimen firmly established that the species could not be classified as a species of Eurypterus and it was thus placed in the new genus Salteropterus, named in honour of John William Salter.[1] Though eurypterid genera are not normally described based only on features of the telson, Salteropterus is considered so different and distinct that comparisons with other genera is redundant.[1]

In 1961, Kjellesvig-Waering suggested that the fragmentary and dubious Slimonia species S. stylops might be synonymous with Salteropterus abbreviatus. The known fossil of S. stylops consists of a single carapace that could potentially belong to any of those species found in Herefordshire that lack a known carapace. In particular, Hughmilleria acuminata and Salteropterus are good candidates as those are close relatives. Kjellesvig-Waring considered Salteropterus to be the best candidate as it is the most closely related to Slimonia itself.[3] As the only known specimen of S. stylops is at an unknown location, further study of the specimen is impossible and it is treated as a nomen dubium.[4]

The dubious species S. longilabium was named by Kjellesvig-Waering in 1961 to refer to a partial metastoma (specimen number 39386 in the collection of the British Museum of Natural History) discovered by Alfred Marston in around 1855 in Leintwardine, England. This specimen was first incorrectly referred to a species of Carcinosoma (C. punctatum) by John William Salter, before he realised that the long and narrow metastoma could not belong to Carcinosoma, but rather to a genus similar to Slimonia. Due to a multitude of features, such as the lack of a cordated area, the metastoma can not be referred to Slimonia however, and the only genus closely enough related to Slimonia in the correct region and period of time is Salteropterus, making its assignment to the genus dubious. Further supporting the assignment of the metastoma to Salteropterus is the discovery of a tergite (specimen number 89597 in the collection of the Geological Survey and Museum, London) from the same location as the S. longilabium metastoma that preserves the same sort of ornamentation found in S. abbreviatus.[3]

Classification

Salteropterus is classified as part of the Slimonidae family of eurypterids, within the Pterygotioidea superfamily, alongside Slimonia.[5] Slimonidae was first erected as a taxon by Nestor Ivanovich Novojilov in 1968 to contain Slimonia, previously considered part of the family Hughmilleriidae since 1951. Slimonia had previously been considered a pterygotid since its description in 1856.[6]

A close relationship between Salteropterus and Slimonia was first suggested when Kjellesvig-Waering erected Salteropterus in 1951, noting that the last three opithosomal segments (segments part of the opisthosoma, the abdomen) were elongated and tapering similarly to those of Slimonia. After Kjellesvig-Waering suggested that the carpace referred to as "Slimonia stylops" might represent the carapace of Salteropterus, the two genera began to be treated as close relatives. Following these studies, Salteropterus was placed in the Slimonidae by V. P. Tollerton in 1989.[7]

The cladogram below is based on the conclusions drawn by O. Erik Tetlie (2004) on the phylogenetic positions of Herefordopterus, Salteropterus and the Pterygotioidea at large following his redescriptions of various eurypterids from Herefordshire, including Salteropterus itself. Salteropterus being more derived than Herefordopterus and Hughmilleria was supported by the fact that Salteropterus partially lacks the appendage spinosity noted in the two hughmilleriid genera, which possess paired spines on four to five of their podomeres, Salteropterus only have one pair of spines on the sixth podomere of the fourth appendage, otherwise completely lacking them.[4]

| Pterygotioidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

The Late Silurian of Herefordshire was home to a wide array of different eurypterids, including species of Erettopterus, Eurypterus, Nanahughmilleria, Marsupipterus, Herefordopterus and potentially Slimonia (depending on the identity of S. stylops). Salteropterus lived in a benthic environment near an intertidal sandy shore and intertidal sandy mudflat environments.[8] This eurypterid fauna coexisted with lingulids, ostracods and cephalaspidimorph fish, such as Hemicyclaspis and Thelodus.[9]

Fossil evidence of the related Slimonia has been interpreted by some researchers as evidence that it was very flexible laterally (side to side). A specimen of Slimonia acuminata from the Patrick Burn Formation of Scotland preserves a complete and articulated series of telsonal, postabdominal and preabdominal segments. In the specimen, the "tail" is bent to a considerable degree previously unseen in any eurypterid. Capable of bending its tail from side to side, it was then theorised that the tail may have been used as a weapon. As the telson spike is elongated and serrated, researchers determined that it would likely have been able to pierce potential prey.[10] However, the revelation that this particular specimen was a molt, rather than an actual carcass, and apparent signs of disarticulation means that this theory is unlikely.[6]

Unlike Slimonia, the telson spike of Salteropterus is not serrated, though it is even more elongated. As the telson spike ends in an unusual structure, and not a sharp point, it is unlikely that Salteropterus could have used its telson in the same way. It is more likely that Salteropterus fed much like other eurypterids without additional specialised weaponry, similarly to modern horseshoe crabs,[11] by grabbing and shredding food with its appendages before pushing it into its mouth using its chelicerae (the frontal appendages).[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1951). "Downtonian (Silurian) Eurypterida from Perton, near Stoke Edith, Herefordshire". Geological Magazine. 88 (1): 1–24. Bibcode:1951GeoM...88....1K. doi:10.1017/S0016756800068874. ISSN 1469-5081. S2CID 129056637.

- 1 2 3 Salter, J. W. (1859). "On some New Species of Eurypterus; with Notes on the Distribution of the Species". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 15 (1–2): 229–236. doi:10.1144/gsl.jgs.1859.015.01-02.48. S2CID 128767648.

- 1 2 3 Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1961). "The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland". Journal of Paleontology. 35 (4): 789–835. JSTOR 1301214.

- 1 2 3 Tetlie, O. Erik (2006). "Eurypterida (Chelicerata) from the Welsh Borderlands, England". Geological Magazine. 143 (5): 723–735. Bibcode:2006GeoM..143..723T. doi:10.1017/S0016756806002536. ISSN 1469-5081. S2CID 83835591.

- ↑ Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2015. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch , version 16.0 http://www.wsc.nmbe.ch/resources/fossils/Fossils16.0.pdf (PDF).

- 1 2 Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1964). "A Synopsis of the Family Pterygotidae Clarke and Ruedemann, 1912 (Eurypterida)". Journal of Paleontology. 38 (2): 331–361. JSTOR 1301554.

- ↑ Tollerton, V. P. (1989). "Morphology, taxonomy, and classification of the order Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843". Journal of Paleontology. 63 (5): 642–657. doi:10.1017/S0022336000041275. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 46953627.

- ↑ Burkert, C (2018-03-21). "Environment preference of eurypterids–indications for freshwater adaptation?".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Fossilworks - Eurypterid-Associated Biota of the Temeside Shale, Ludlow and Perton, England (Silurian of the United Kingdom)". fossilworks.org.

- ↑ Persons, W. Scott; Acorn, John (2017). "A Sea Scorpion's Strike: New Evidence of Extreme Lateral Flexibility in the Opisthosoma of Eurypterids". The American Naturalist. 190 (1): 152–156. doi:10.1086/691967. PMID 28617636. S2CID 3891482.

- ↑ Daniel I., Hembree; Platt, Brian F.; Smith, Jon J. (2014). Experimental Approaches to Understanding Fossil Organisms: Lessons from the Living. Springer Science & Business. p. 77. ISBN 978-9401787208.

- ↑ "Horseshoe Crabs, Limulus polyphemus". MarineBio.org. Retrieved 2018-03-21.