| Salar Ignorado | |

|---|---|

At the top, the third one. | |

Salar Ignorado | |

| Coordinates | 25°29′52″S 68°37′17″W / 25.49778°S 68.62139°W[1] |

Salar Ignorado is a salar (salt flat) in the Andes of Chile's Atacama Region at 4,250 metres (13,940 ft) elevation. Located just south of Cerro Bayo volcano, it comprises 0.7 square kilometres (0.27 sq mi) of salt flats, sand dunes and numerous pools of open water. The waters of Salar Ignorado, unlike these of other salt flats in the central Andes, are acidic owing to the input of sulfuric acid from hydrothermal water and the weathering of volcanic rocks.

The salt flat is located in a harsh climate with strong winds, large temperature fluctuations, intense insolation and aridity. Gypsum crystals develop in the pools of water and are redeposited by wind to form the dunes. Liquids and microorganisms are occasionally trapped within the crystals. The environment of Salar Ignorado has drawn comparisons to early Earth.

Geography and geomorphology

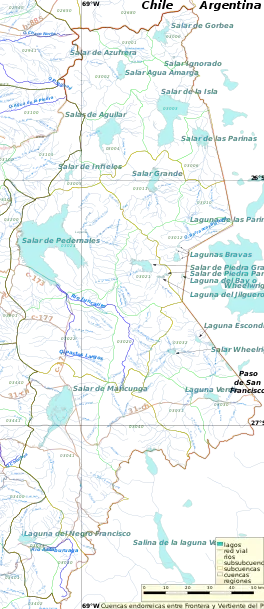

The salt pan is in the Chilean Andes, and, not far from the border with Argentina,[2] within the northernmost tip of the Chilean Atacama Region.[3] It is located east of Plato de Sopa volcano[4] and just south of the 5,400 metres (17,700 ft) high Cerro Bayo Complex volcano. Salar Gorbea is just northwest of Salar Ignorado[lower-alpha 1].[1] The area is difficult to access.[6]

Salar Ignorado is triangular with a surface area of 0.7 square kilometres (0.27 sq mi) at 4,250 metres (13,940 ft) elevation,[1] and salt-free benches delimit its shores.[7] The surface of the salt flat is not actually flat and features a hummocky topography with heights of 2 metres (6 ft 7 in).[8] About one third is made up by pools of open water, the rest are sand dunes and salar flats. Pools are less than 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) deep but reach widths of 2–50 metres (6 ft 7 in – 164 ft 1 in). They form either when strong winds blow out part of the salar surface and the shallow groundwater floods the resulting depressions,[9] or from the ongoing dissolution of salts in the salt-undersaturated brines below.[10] Crystals of gypsum grow in the pools, forming sea urchin-like shapes and mounds.[11] Part of the groundwater reaches the surface and evaporates, leaving small gypsum crystals behind that are reworked by winds and form the dunes.[9] They also form snow-like surface deposits around the margins of the pools.[11] There is no evidence of former shorelines around Salar Ignorado.[12] Only one inflow was identified during reconnaissance reported in 2002[13] and leads to a small lagoon at the northern end of Salar Ignorado.[14] A dry channel runs from Salar Ignorado to Salar Gorbea, through which Salar Ignorado may have spilled into Salar Gorbea in the past.[15] Otherwise, both Salar Ignorado and Salar Gorbea are closed basins.[16]

The catchment of Salar Ignorado has a surface area of about 37.5 square kilometres (14.5 sq mi)[1] and is devoid of vegetation,[9] with a maximum elevation of about 5,100 metres (16,700 ft).[17] It consists of heavily eroded and hydrothermally altered Miocene volcanoes[18] that formed on a Paleozoic basement. The volcanoes feature large deposits of hydrothermally altered rock and native sulfur.[6] The landscape is dominated by hills and mountains,[19] and volcanic sediments with grain sizes ranging from boulders to sand cover the terrain surrounding Salar Ignorado.[20]

Hydrology and minerals

Water temperatures in the salar pools range from 9–15 °C (48–59 °F). The waters contain sodium and sulfate as their main salt components,[9] with salt concentrations ranging between 4043–97091 mg/L.[17] Salar Ignorado is one of the rare salars with acidic waters in northern Chile and Bolivia,[21] with its neighbour Salar de Gorbea the only other one there.[2] The waters of Salar Ignorado are unsuitable for irrigation or drinking water use.[22]

The most common mineral deposited at Salar Ignorado is gypsum,[21] but bassanite, epsomite, halite, jarosite[9] and thenardite also occur.[13] The gypsum crystals contain fluid inclusions that often have a complex history[23] and contain H

2S bubbles.[24] Large gypsum crystals are cemented by smaller crystals.[25] Groundwater precipitates minerals like alunite, hematite, jarosite and kaolinite.[26]

The acidity is unusual for salars in Chile and there is no obvious reason for it in the geology of the area.[27] It appears to originate from hydrothermal and magmatic processes[23] that generate sulfuric acid and consume the rocks' buffering capacity. Sulfur and iron oxidation gives rise to acids that in turn leach mineral components of rocks.[28] Most of the water likewise is of hydrothermal and magmatic origin[23] while direct precipitation plays a minor role.[29] It is possible that Salar Ignorado and Gorbea were normal salars before hydrothermal alteration of the surrounding volcanoes set in.[30] The inflow of Salar Ignorado is the most sulfate-rich of all studied Andean salars.[31] A peak of solute input to Salar Ignorado took place between 120,000 and 11,000 years ago during the Pleistocene, during a humid period.[32] Volcanic uplift occurs in the region at a rate of 2.5 centimetres per year (0.98 in/year);[26] fluctuations in the regional magmatic system may have triggered intrusions of groundwater into the salar but these events have not been dated.[12]

Climate and ecology

Mean temperatures are about −2 °C (28 °F) but fluctuations of 1–25 °C (34–77 °F) were documented in summer months.[9] Mean precipitation is about 140 millimetres (5.5 in) per year and evaporation reaches 1,000 millimetres (39 in) per year.[17] The region is one of the driest on Earth[21] and has a harsh climate with strong winds, dust devils and high insolation.[26] This climate may have persisted since the Miocene or even Eocene and prevents the formation of glaciers and visible surface flow.[9]

Diatoms, green algae such as Dunaliella and prokaryotes live inside the gypsum crystals,[11] with cells both within the solid crystals and the fluid inclusions.[24] Microbial mats grow on the bottom of shallow pools.[33] The bacterial species variety of Salar Ignorado and the bacterial biomass are small.[34] Ecosystems at Salar Ignorado may resemble these of early Earth.[35]

There is no evidence of crustaceans at Salar Ignorado.[36] Only one mammal was observed in the area during a reconnaissance reported in 2013,[5] and a vicuña skeleton was reported in 2008.[36]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 492.

- 1 2 Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 491.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 148.

- ↑ Pueyo et al. 2021, p. 5.

- 1 2 Universidad de Antofagasta, Institut de recherche pour le développement & Haimaitier Institute 2013, p. 93.

- 1 2 Risacher, Alonso & Salazar 2002, p. 42.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 152.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 493.

- ↑ Risacher, Alonso & Salazar 2002, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 494.

- 1 2 Pueyo et al. 2021, p. 14.

- 1 2 Risacher, Alonso & Salazar 2002, p. 43.

- ↑ Risacher, Alonso & Salazar Méndez 1999, p. 16.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 164.

- ↑ Escudero et al. 2018, p. 1403.

- 1 2 3 Risacher, Alonso & Salazar 2003, p. 253.

- ↑ Pueyo et al. 2021, p. 3.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 149.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 490.

- ↑ Risacher, Alonso & Salazar Méndez 1999, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 502.

- 1 2 Karmanocky & Benison 2014, p. 24.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 Karmanocky & Benison 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Risacher, Alonso & Salazar Méndez 1999, p. 6.

- ↑ Pueyo et al. 2021, p. 2.

- ↑ Karmanocky & Benison 2016, p. 503.

- ↑ Risacher, Alonso & Salazar 2002, p. 52.

- ↑ Risacher, Alonso & Salazar 2002, p. 55.

- ↑ Pueyo et al. 2021, p. 13.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 159.

- ↑ Universidad de Antofagasta, Institut de recherche pour le développement & Haimaitier Institute 2013, p. 63.

- ↑ Benison 2019, p. 165.

- 1 2 Benison 2019, p. 162.

Sources

- Benison, Kathleen C. (2019-02-21). "The Physical and Chemical Sedimentology of Two High-Altitude Acid Salars in Chile: Sedimentary Processes In An Extreme Environment". Journal of Sedimentary Research. 89 (2): 147–167. Bibcode:2019JSedR..89..147B. doi:10.2110/jsr.2019.9. ISSN 1527-1404. S2CID 135031173 – via ResearchGate.

- Karmanocky, F.J.; Benison, K.C. (2014). Fluid inclusion petrography, microthermometry, and geobiology in modern gypsum from acid saline Salar Ignorado, northern Chile (PDF). Pan-American Current Research on Fluid Inclusions (PACROFI-XII). Vol. 23.

- Karmanocky, F. J.; Benison, K. C. (August 2016). "A fluid inclusion record of magmatic/hydrothermal pulses in acid Salar Ignorado gypsum, northern Chile". Geofluids. 16 (3): 490–506. doi:10.1111/gfl.12171.

- Escudero, Lorena; Oetiker, Nia; Gallardo, Karem; Tebes-Cayo, Cinthya; Guajardo, Mariela; Nuñez, Claudia; Davis-Belmar, Carol; Pueyo, J. J.; Chong Díaz, Guillermo; Demergasso, Cecilia (1 August 2018). "A thiotrophic microbial community in an acidic brine lake in Northern Chile". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 111 (8): 1403–1419. doi:10.1007/s10482-018-1087-8. ISSN 1572-9699. PMID 29748902. S2CID 13684197.

- Pueyo, JuanJosé; Demergasso, Cecilia; Escudero, Lorena; Chong, Guillermo; Cortéz-Rivera, Paulina; Sanjurjo-Sánchez, Jorge; Carmona, Virginia; Giralt, Santiago (2021-07-20). "On the origin of saline compounds in acidic salt flats (Central Andean Altiplano)". Chemical Geology. 574: 120155. Bibcode:2021ChGeo.574l0155P. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120155. hdl:2445/184092. ISSN 0009-2541. S2CID 233653266.

- Risacher, François; Alonso, Hugo; Salazar Méndez, Carlos (January 1999). Geoquímica de aguas en cuencas cerradas: I, II, III regiones - Chile (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Dirección General de Aguas.

- Risacher, François; Alonso, Hugo; Salazar, Carlos (2002-07-01). "Hydrochemistry of two adjacent acid saline lakes in the Andes of northern Chile". Chemical Geology. 187 (1): 39–57. Bibcode:2002ChGeo.187...39R. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00021-9. ISSN 0009-2541.

- Risacher, François; Alonso, Hugo; Salazar, Carlos (2003-11-01). "The origin of brines and salts in Chilean salars: a hydrochemical review". Earth-Science Reviews. 63 (3): 249–293. Bibcode:2003ESRv...63..249R. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(03)00037-0. ISSN 0012-8252.

- Universidad de Antofagasta; Institut de recherche pour le développement; Haimaitier Institute (2013). Evaluación biogeoquímica de aguas en cuencas cerradas altoandinas de la región de Atacama. Bases científicas del recurso hídrico para la innovación y la competitividad. Informe final (PDF) (Report).