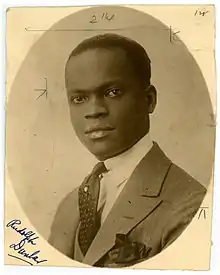

Rudolph Dunbar | |

|---|---|

Rudolph Dunbar, ca. 1920 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 26 November 1907 Nabacalis, British Guiana |

| Died | 10 June 1988 (aged 80) London, United Kingdom |

| Genres | Classical, jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Conductor, musician, composer, journalist |

| Instrument(s) | Clarinetist, and composer |

Rudolph Dunbar (26 November 1907[1][2] – 10 June 1988) was a Guyanese conductor, clarinetist, and composer, as well as being a jazz musician of note in the 1920s.[3] Leaving British Guiana at the age of 20, he had settled in England by 1931, and subsequently worked in other parts of Europe but lived most of his later years in London. Among numerous "firsts", he was the first black man to conduct the London Philharmonic Orchestra (1942), the first black man to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic (1945) and the first black man to conduct orchestras in Poland (1959) and Russia (1964).[4] Dunbar also worked as a journalist and a war correspondent.

Biography

Early years

Dunbar was born in Nabacalis, British Guiana.[4] He began his musical career playing clarinet with the British Guiana militia band at the age of 14,[1] before moving to New York at the age of 20.[5] He studied at the Institute of Musical Art (now Juilliard), and while in New York was also involved with the Harlem jazz scene, performing in 1924 with the Harlem Orchestra, and befriending the composer William Grant Still who played piano in the orchestra.[3]

In 1925, Dunbar moved to Paris and between 1927 and 1929 attended the Sorbonne, where he studied conducting with Philippe Gaubert, composition with Paul Vidal, and the clarinet with Louis Cahuzac.[6] In Paris, as Ian Hall wrote, "Madame Debussy, widow of Claude Debussy, invited [Dunbar] to give a private recital at her home in the presence of influential members of the Conservatoire de Musique."[7] According to author John Cowley, Dunbar was in England in 1927, when he joined the Plantation Orchestra for a road tour of the show Blackbirds of 1927.[8] Dunbar also spent time studying in Vienna with Felix Weingartner.[6] His hopes of a degree were ended by the death of his father.[9]

By 1931, Dunbar had settled in London, where he founded the Rudolph Dunbar School of Clarinet Playing.[5] He wrote columns as a technical expert in the Melody Maker for seven years[4] and in 1939 published his Treatise on the Clarinet (Boehm System), which became a standard text about the instrument.[10]

His ballet, Dance of the Twenty-First Century, written for Cambridge University's Footlights Club, was premiered in the US in 1938 on an NBC broadcast.[4] Around this time he was also performing duo recitals with the composer Mary Lucas, including her own compositions. A recording of them playing her Lament for clarinet and piano was issued by Octacros Records in the late-1930s and is among several performances that have now been digitized at the British Library.[11]

Dunbar made appearances on the BBC in 1940 and 1941, and became the first black man to conduct the London Philharmonic in 1942 at a concert in the Royal Albert Hall, London, before an audience of 7,000.[5] In September 1945 he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic at the invitation of music director Leo Borchard, performing William Grant Still's Afro-American Symphony before Allied servicemen.[12] According to J. A. Rogers, that same year Dunbar "conducted the Concerts Colonne of Paris, Concerts Pasdeloup, Orchestre National de France, and the Concerts du Conservatoire in a Festival of American Music in Paris for which he received superlative praise from the French press and leading conductors as Claude Delvincourt, director of the National Conservatory of Music, and Paul Parry."[13] Dunbar also conducted in 1948 at the Hollywood Bowl.[5] In 1962, he conducted eight orchestras on a tour of Poland, and two years later he visited Russia, where he conducted the Leningrad Philharmonic, the Moscow State Symphony Radio and TV Orchestra, and the Baku Philharmonic at a concert in Krasnodar, North Caucasus.[14]

He was reported as having said: "The success I have achieved through sacrifice and struggle is not for myself, but for all the colored people."[15]

He championed the music of other black composers, particularly the African-American Still, alongside whom he had played in the Harlem Orchestra in the 1920s,[16] and the autograph of Still's Festive Overture of 1944 is dedicated "To my dear friend, Rudolph Dunbar".[16]

Journalism

Dunbar also worked as a journalist. He became London correspondent for the Associated Negro Press news service in 1932, and in 1936 reported for them on debates in the House of Commons on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. During World War II, he frequently reported in the American press on the atrocities committed by Nazis against Black people.[10] Additionally he was a war correspondent with the American 8th Army and crossed the English Channel on D-Day. He reputedly distinguished himself by warning the US Artillery Battalion of an ambush near Marchin during the Battle of the Bulge.[5]

Later life

Dunbar's music career waned in the post-war period, which he attributed to his ethnicity. He lived most of his later life in London, where he died of cancer in 1988.[5]

In 1975, the Rudolph Dunbar Archive was established as part of the James Weldon Johnson Memorial collection at Yale University.[9]

Writings

References

- 1 2 "Rudolph Dunbar, a talented international clarinetist with many 'firsts'", African American Registry.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography gives his birth year as 1899.

- 1 2 Rudolph Dunbar profile, British Jazz History, Jazz Services.

- 1 2 3 4 "W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor", The Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Autumn 1981), pp. 193–225.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Miranda Kaufmann, "Dunbar, Rudolph (1899-10 June 1988)", in David Dabydeen, John Gilmore & Cecily Jones, Oxford Companion to Black British History, 2007.

- 1 2 Bob Shingleton, "Berlin Philharmonic's first Black conductor", On An Overgrown Path, 23 April 2007.

- ↑ "Musical pioneer: Guyanese conductor, Rudolph Dunbar". Stabroek News. 10 January 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ↑ John Cowley, "London is the Place: Caribbean Music in the Context of Empire 1900–60", in Paul Oliver (ed.), Black Music in Britain: Essays on the Afro Asian Contribution to Popular Music, Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1990, pp. 57–76.

- 1 2 Dominique de Lerma, "Rudolph Dunbar, conductor – On Black Classical Music", The Afro American, 24 June 1978.

- 1 2 Thurman, Kira (2021). Singing Like Germans: Black Musicians in the Land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9781501759840.

- ↑ Michael Thomas: Octaras

- ↑ Monod, David (2005). Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, & the Americans, 1945–1953. University of North Carolina Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-8078-2944-7.

- ↑ J. A. Rogers, "Rudolph Dunbar", in World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2 (1947), Touchstone, 1996, p. 563.

- ↑ William H. Stoneman, "Rudolph Dunbar, Good Will Envoy", Chicago Daily News, 19 May 1966. Reprinted in W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor, The Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 9, No. 2, Autumn 1981 (pp. 193–225), p. 225.

- ↑ "Conductor's Life Parallels Alger's: Rudolph Dunbar Came Up Hard Way; Now Tops Field", The Afro-American, 1 February 1947.

- 1 2 Dabrishus, Michael J.; Carolyn L. Quin; Judith Anne Still (1996). William Grant Still: a bio-bibliography. Greenwood Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-313-25255-6..

External links

- A biography on Rudolph Dunbar on the blog On An Overgrown Path

- Corbis Images, "Rudolph Dunbar Conducting Orchestra. Original caption: 9/25/1945-Berlin, Germany: The Nazi racial prejudice suffered another blow recently when Rudolph Dunbar, brilliant American Negro conductor, led the Berlin Philharmonic orchestra at two concerts in Berlin's Titania Palast. Dunbar, seen conducting during one of the concerts, will leave shortly for Paris where he will conduct a festival of American music in a series of four concert."

- Judith Walkowitz, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London, Yale University Press, 2012, p. 236: illustration reproducing Dunbar's article "Harlem in London: Year of Advancement for Negroes" from Melody Maker, 7 March 1936 (p. 2).

- Rudolph Dunbar Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.