Robert Maxwell, 1st Earl of Nithsdale (after 1586 – May 1646), was a Scottish nobleman. He succeeded his brother as 10th Lord Maxwell in 1613,[2] and was created Earl of Nithsdale in 1620. General of Scots in Danish-Norwegian service during the Thirty Years' War. A loyal supporter of Charles I and a prominent Catholic, he lost his titles and estates in 1645, dying on the Isle of Man in 1646.

Biography

The noble House of Maxwell had held the castle of Caerlaverock near Dumfries since the 13th century, and by the mid-16th century were the most powerful family in south-west Scotland. Robert Maxwell was the second son of John Maxwell, 8th Lord Maxwell (1553–1593) and his wife Elizabeth Douglas (d.1637), daughter of the 7th Earl of Angus. John Maxwell was killed at Dryfe Sands, near Lockerbie during a feud with the Johnstones of Annandale. His eldest son, John Maxwell, 9th Lord Maxwell, continued the feud and was executed in 1613 for the revenge killing of Sir James Johnstone. His lands and titles were forfeited, but in 1617 they were restored to Robert Maxwell by Parliament.[3]

King James gave Maxwell £2,000 sterling in October 1617 to help his "distressed estate."[4] In July 1619, Maxwell was appointed to the Privy Council of Scotland. On 28 October 1619, he married Elizabeth Beaumont, daughter of Sir Francis Beaumont and cousin of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham. Buckingham was the principal favourite of King James VI and I, and this family connection may have assisted Maxwell's progress.[3] On 29 August 1620, Maxwell was created Earl of Nithsdale by King James. This creation was held to be a confirmation of the earldom of Morton which had been granted to his father in 1581, but which was subsequently returned to the Douglas family. The following year the family lands were regranted to him by charter.[3] However, arguments about precedency continued, with holders of earldoms granted after 1581 claiming precedency over Nithsdale, and in November 1620 this held up Privy Council business.[5]

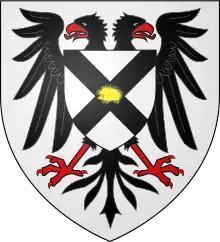

Soon after, he began work on a building project at Caerlaverock, creating a Renaissance mansion within the medieval castle walls. Known as the Nithsdale Lodging, this has been described as among "the most ambitious early classical domestic architecture in Scotland".[6] Completed in 1634, the facade bears carvings of his coat of arms (a double-headed eagle) and crest (a stag). Its original contents were detailed in an inventory made after the siege, including a drawing chamber for Lady Nithsdale furnished in cloth-of-silver.[7]

By 1623 he was in money trouble again, and wrote to Viscount Annand that he was angered by a false rumour that he and his wife were imminently "up-coming" to London, where her expenses and spending would be a waste, "wasturrie". He insisted that Lady Nithsdale would not be coming to court in future unless at Buckingham's request. Nithsdale was trying to borrow money from the jeweller George Heriot, who was reluctant to lend. Nithsdale thought uncertainty over the Spanish match had led to a lack of credit in Scotland, writing "the miserie of this land is such. God send the prince and my lord duke well home."[8] In May 1624 he came to London and stayed at Denmark House the residence of Anne of Denmark, and obtained permission from the king to travel abroad, while Lady Nithsdale stayed at Caerlaverock with their children.[9]

Nithsdale attended the funeral of King James,[10] and following the accession of Charles I in 1625, he proved a loyal supporter. He was elected as General of the Scottish army levied to fight in Denmark during the Thirty Years' War. His staunch Catholicism was mentioned in his patent of promotion to Christian IV as not being problematic.[11] However, his fellow Scottish colonels disagreed, in particular Alexander Lindsay, and Lord Spynie.[12] As a result, the Scots served in separate brigades within the Danish-Norwegian Army. As a Catholic, he was a natural ally of his own King, Charles I against the Presbyterian Scots. When Charles attempted to impose an Anglican prayer book in Scotland in July 1637, riots broke out, leading to the signing of the National Covenant. Nithsdale was at Caerlaverock in August 1637, and wrote to Sir Richard Graham for dogs for hunting and breeding.[13]

Relations between Charles and the Scots deteriorated further until the outbreak of the Bishops' Wars of 1639 and 1640, one of the triggers of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Despite his loyalty, Charles left Nithsdale to take care of himself in March 1640, promising him assistance when it became possible.[14] He found himself besieged at Caerlaverock by an army of Covenanters led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Home. Nithsdale, with a garrison of 200, held out for 13 weeks before surrendering.[15]

In 1644 he assisted in the defence of Newcastle upon Tyne, which held out against Parliament for seven months during the Siege of Newcastle, and was one of the "diehards" who took refuge in the Castle when the town fell. They surrendered after a few days on a promise of mercy, which was kept. In 1645 his lands and titles were declared forfeit, and he fled to the Isle of Man where he died the following year.[3]

Lord Nithsdale and his wife Elizabeth had three children:[3]

- Robert Maxwell, 2nd Earl of Nithsdale (1620–1667), restored to the earldom in 1647.

- Jean (died 1649), served during the Thirty Years' War as an officer in Southwest Germany. He was mentioned in 1634 in the fortress of Hohenurach near the city of Urach (today Bad Urach).

- Elizabeth (died young).

References

- ↑ "Nithsdale, Earl of (S, 1620 - forfeited 1716)". Cracroft's Peerage. Heraldic Media Limited. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ He is also recorded as the 9th Lord Maxwell

- 1 2 3 4 5 Balfour Paul, James (1904), "Maxwell, Earl of Nithsdale", The Scots Peerage, Edinburgh: D. Douglas, vol. VI, pp. 482–487

- ↑ HMC Mar & Kellie, vol. 1 (London, 1904), p. 82.

- ↑ The Melros Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1837), pp. 374-6, 388-9.

- ↑ Gifford, John (1996). The Buildings of Scotland. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale. Dumfries and Galloway. p. 140. ISBN 0-300-09671-2.

- ↑ William Fraser, Book of Carlaverock, vol.2 (Edinburgh, 1873), pp. 502-4.

- ↑ The Melros Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1837), p. 544.

- ↑ The Melros Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1837), pp. 560-1.

- ↑ John Nichols, Progresses of James I, vol. 4 (London, 1828), p. 1047.

- ↑ Danish State Archives, TKUA England A1:3. Charles I to Christian IV, 8 February 1627 quoted in Steve Murdoch and Alexia Grosjean, Alexander Leslie and the Scottish Generals of the Thirty Years' War, 1618-1648 (London, 2014), pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Danish State Archives, TKUA England A2: 4, Lord Spynie to Christian IV, 1627 quoted in Steve Murdoch and Alexia Grosjean, Alexander Leslie and the Scottish Generals of the Thirty Years' War, 1618-1648 (London, 2014), pp. 44-46.

- ↑ HMC 6th Report: Graham (London, 1877), p. 335.

- ↑ James Orchard Halliwell, Letters of the Kings of England, vol. 2 (London, 1846), p. 326.

- ↑ Grove, Doreen; Yeoman, Peter (2006). Caerlaverock Castle. Historic Scotland. p. 32. ISBN 1-90-496624-1.